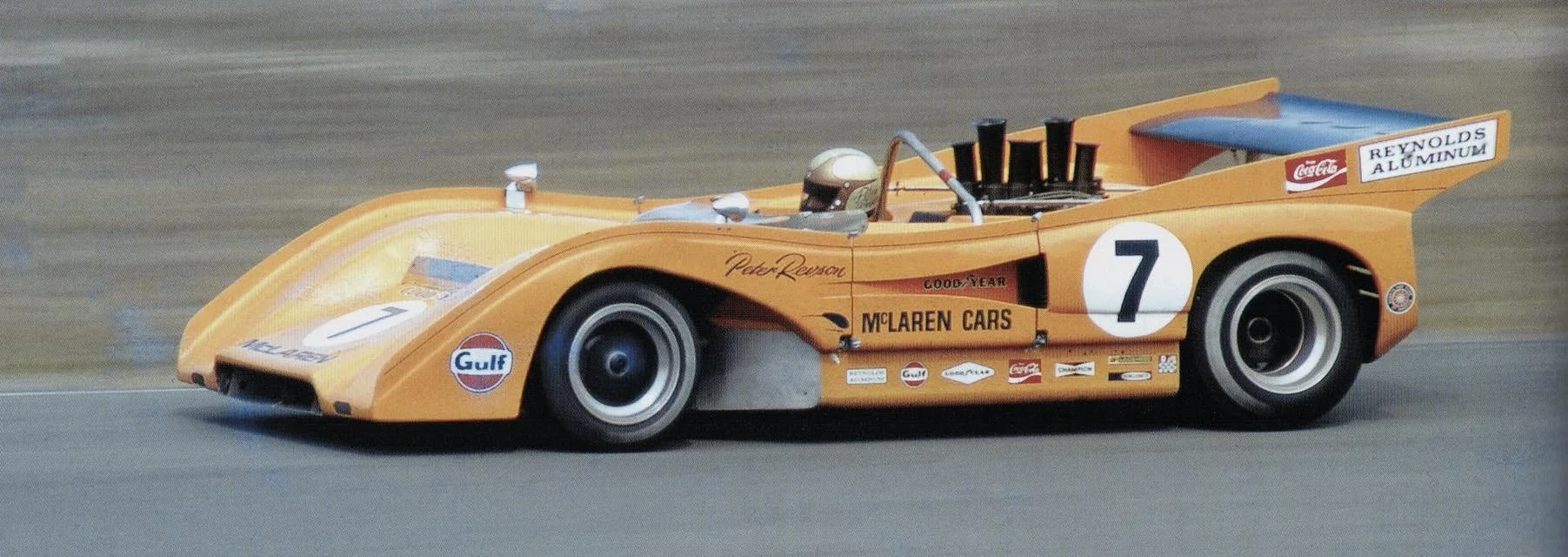

#7 Peter Revson (McLaren M8F-Chevrolet)

#5 Denny Hulme (McLaren M8F-Chevrolet)

#1 Jackie Stewart (Lola T260-Chevrolet)

1971 — The M8F and the Rise of Peter Revson

The 1971 Canadian-American Challenge Cup opened in a strange new quiet. The storm of emotion and endurance that defined 1970 was gone, replaced by a sharper, colder tension. McLaren Cars had survived the death of its founder. It had rebuilt itself in real time, won every race of the season, and proven that discipline could triumph even over grief. But 1971 presented a different kind of uncertainty. The team had lost Dan Gurney, who stepped away from full-time driving. Denny Hulme returned as spiritual anchor, but the physical scars from his Indianapolis fire remained. And into this evolving landscape stepped Peter Revson — quick, analytical, elegant behind the wheel, and possessing the competitive instinct McLaren needed for the next chapter.

This was the debut year of the McLaren M8F, the successor to the M8D and arguably the most complete car the team ever produced in the Group 7 era. It wasn’t a revolution — it didn’t need to be. The M8F was refinement layered upon refinement: more downforce, a broader stance, improved cooling, and a Chevrolet engine that now produced more than 740 horsepower in full song. The papaya silhouette remained unmistakable, but its presence on the grid had taken on a new kind of authority. The orange cars weren’t merely favorites. They were expected to win.

But 1971 would not be a one-team parade. Shadow Racing, founded by the ambitious and unconventional Don Nichols, arrived with their radical, low-slung DN2 prototype — an all-black “spy plane” disguised as a race car. Porsche had committed more fully, bringing the 917/10 spyder that would eventually dominate the next era. Lola, under Carl Haas, fielded improved T222 and T260 designs. And Gene Hamill, George Eaton, Lothar Motschenbacher, and Tony Dean formed a deep and savvy privateer grid.

This was the year when the grid widened. When the competition matured. When Peter Revson took on Denny Hulme — not as a substitute or a caretaker, but as a full, equal, and motivated teammate. It was the year when McLaren Cars, no longer operating under the weight of raw tragedy, began functioning as a dynasty. And it was the year when Revson, elegant and composed, cemented his legacy as one of the most complete drivers of his generation.

1971 did not have the emotional extremes of 1970. But it had something equally powerful: the slow, inexorable rise of a driver who would become the face of McLaren’s final Can-Am chapter.

Round 1 — Mosport Park (June 13, 1971)

Mosport had traditionally set the tone for each Can-Am campaign, and 1971 was no different. The early-summer air was cool and heavy as the new M8Fs were rolled into the Canadian sunshine for the first time. Revson, now the full-time McLaren lead, looked relaxed and confident. Hulme, the reigning champion, was sharper than he had been in years — fitter, focused, and eager to prove that his title had not been won merely under tragic circumstances.

Qualifying established the new order immediately. Revson took pole with a blistering lap, the M8F dancing through the high-speed sweepers with the kind of planted discipline that had become a McLaren trademark. Hulme slotted second, just three-tenths behind. The next fastest challenger — Jackie Stewart in a Carl Haas Lola T260 — was more than a second adrift. Porsche, still learning its new spyder configuration, qualified mid-grid.

The race began with a clean start. Revson led into Turn 1, Hulme tucked in behind, and the two papaya cars began a controlled, calculated escape. Stewart tried to hang with them early, but the Lola simply didn’t have the traction or downforce to match the M8F’s stability through the fast corners. Within ten laps, the McLarens had built a gap measured in entire sectors.

Mid-race, the field suffered its usual attrition. Eaton’s McLaren lost oil pressure. Motschenbacher retired with overheating. And Tony Dean’s Porsche 908 suffered fuel starvation. Through the chaos, Revson remained calm and methodical, lapping backmarkers with the kind of clinical consistency Bruce had once displayed.

With ten laps remaining, Hulme made a small push — not an attack, but a test of pace. Revson responded immediately, matching Hulme’s sector times without sliding the car or abusing the tires. It was a message delivered not with violence, but with precision: this was Revson’s season to command.

Revson crossed the line for his first Can-Am victory. Hulme finished second. Stewart’s Lola, the only non-McLaren within sight, finished a distant third. And the paddock understood that the new era had begun.

Round 2 — St. Jovite (June 27, 1971)

Mont-Tremblant offered a different test altogether: elevation changes, mid-speed rhythm, and a technical flow that punished impatience. Hulme, who excelled on such circuits, delivered a masterful qualifying run to take pole by the slimmest margin over Revson. Stewart again qualified third but remained unable to break within the papaya window.

The race began under warm skies. Hulme launched perfectly, taking an immediate lead. Revson stayed glued to his rear wing, studying his teammate’s lines with quiet intensity. For the first twenty laps, the two McLarens traded sector times like synchronized metronomes — one tenth lost, one tenth regained, lap after lap.

But as the race progressed, Revson began to apply pressure. He braked a little deeper into the downhill hairpin. He hugged the inside line more aggressively at Namerow Corner. Hulme held firm, but the subtle cracks appeared — slightly earlier turn-in, longer throttle lift, hints that the world champion was defending rather than controlling.

Near lap 40, Revson made his decisive move. Exiting the uphill esses, he carried a fraction more speed and slid alongside Hulme into the braking zone. It was a clean, elegant pass — the kind Bruce McLaren would have applauded.

From there, Revson controlled the race with calm authority. Hulme settled into second, choosing not to wage an internal war that could cost the team points. Stewart held third but never threatened.

When Revson crossed the line, he raised his fist for the first time that season — not in celebration, but in confirmation. Mosport had been a declaration. St. Jovite was proof.

Round 3 — Road Atlanta (July 11, 1971)

Road Atlanta, still new to Can-Am, was a violent combination of high-speed bends, flowing esses, and punishing undulations. It was a circuit that rewarded bravery — but punished ego. Revson and Hulme knew this, and their qualifying laps reflected the balance of intelligence and aggression that had now come to define McLaren’s internal duel.

Revson claimed pole by just over one-tenth. Hulme stood beside him. The rest of the field — Stewart, George Follmer, and Motschenbacher — formed the familiar pack of hopefuls chasing the papayas’ shadow.

At the green flag, Revson launched perfectly. Hulme stayed close, refusing to let the younger driver slip away. Stewart made a daring attempt to dive beneath Hulme at Turn 5, but the Lola’s instability prevented him from committing, and he tucked back into third.

Mid-race brought danger. Oil spilled from a backmarker’s engine through the downhill esses. Revson encountered it first, catching the slide with breathtaking reflex and maintaining control. Hulme, arriving moments later, narrowly avoided disaster by choosing an outside line through the slickest patch. Several others spun, including Stewart.

The McLarens remained faultless through the chaos. Revson maintained pace; Hulme stabilized. Stewart recovered but fell too far behind to matter.

In the final laps, Revson extended his lead to a comfortable margin. When he crossed the line, it became his third consecutive victory — a performance that left the paddock whispering whether 1971 might become a coronation rather than a contest.

Round 4 — Mid-Ohio (August 1, 1971)

Mid-Ohio’s compact, technical layout offered the grid its best chance yet to break McLaren’s stranglehold. Its short lap time made traffic unpredictable. Its corners rewarded nimble cars like the Lola more than the brute powerhouses like the M8F. Stewart entered the weekend believing he had a real shot.

Revson claimed pole. Stewart produced a stunning lap for second. Hulme qualified only third — his worst grid position of the season — after struggling to find balance in the tighter sections.

At the start, Revson led into Turn 1, but Stewart held second and pressed the challenge. Hulme remained third, evaluating the Lola’s lines and waiting for a weakness. For the first twenty laps, Stewart looked genuinely competitive — the closest he had been to a McLaren all season.

But then, predictably, the McLaren strengths reasserted themselves. On high-load corners, the M8F’s downforce overwhelmed the Lola. On exit traction, the Chevy torque delivered fractions of acceleration that Stewart simply couldn’t mimic. Revson extended his lead gradually, clinically.

Hulme, now comfortable with fuel burn-off and tire wear, increased his pace. Stewart defended bravely, but by lap fifty, the challenge collapsed. Hulme seized second, Revson remained untouchable, and Stewart faded into another distant third.

Revson claimed his fourth straight victory. Hulme once again played anchor. And the field’s best chance of upsetting the papayas evaporated into the Mid-Ohio humidity.

Round 5 — Road America (August 29, 1971)

Road America was the kind of circuit that demanded everything — horsepower, high-speed stability, bravery, and strategic discipline. It was also a track where Hulme traditionally excelled.

Qualifying remained consistent. Revson on pole. Hulme a hair behind. Stewart third. The gaps were smaller, but the order unchanged.

The race began with Revson leading through Turn 1. Hulme stayed glued to him, closer than he had been all season. Drafting down the Moraine Sweep, Hulme made an aggressive inside move into Turn 5 — the kind of calculated strike only veterans attempt. Revson yielded, unwilling to risk contact.

Hulme now controlled the race — for once, making Revson the hunter, not the hunted. The crowd sensed a shift. The papaya cars remained in command, but the internal balance had changed.

Mid-race traffic tightened the battle. Revson closed the gap, gaining time through the Carousel and Canada Corner. Hulme held firm, adjusting his defensive lines with surgical precision.

In the final ten laps, Revson made his ultimate attempt — drafting Hulme down the front straight, pulling alongside into Turn 1. But Hulme refused to yield. The door closed. The world champion held track position and kept the younger driver behind him.

Hulme crossed the line for his first win of 1971. Revson finished second but remained championship leader. Stewart again completed the podium.

For the first time, the battle within McLaren felt truly alive.

Round 6 — Donnybrooke (September 12, 1971)

Donnybrooke’s long straights and flat layout favored raw engine power — an area where McLaren held an undeniable advantage. But this would become the weekend when the field mounted its strongest challenge yet.

Revson qualified on pole. Hulme second. Stewart third. But Gene Hamill, in a privately run McLaren, produced a surprising fourth-place qualifying time. And Tony Dean, in the Porsche 908, showed unusual confidence.

At the green flag, Revson surged ahead. Hulme followed. Stewart and Hamill battled fiercely into Turn 1. But the real threat emerged from behind — the Porsche picked up momentum as its lighter weight kept tire wear low.

Mid-race attrition struck the midfield hard. Several Lolas retired with mechanical issues. Hamill’s McLaren suffered gearbox trouble. Stewart encountered brake fade.

Through all this, Revson drove flawlessly. Hulme maintained second, comfortably ahead of Stewart’s fading Lola. But with ten laps remaining, the Porsche suddenly emerged — Dean slicing through the field with aggressive late-race pace.

Gethin, Motschenbacher, and Hamill were all overtaken. Only the papaya cars remained ahead.

Revson, sensing the late threat, increased his pace. Hulme responded. The Porsche kept pushing — but ran out of laps.

Revson won. Hulme second. The Porsche third. Stewart fourth.

Another papaya 1–2 — but the margin had tightened.

Round 7 — Laguna Seca (September 26, 1971)

Laguna Seca traditionally favored downforce, braking discipline, and efficient mechanical balance — the hallmarks of the M8F.

Revson once again qualified on pole. Hulme started alongside. Stewart, still unable to close the gap fully, qualified third. And George Follmer, in a customer McLaren, lined up fourth.

When the race began, Revson maintained his lead through the Andretti Hairpin. Hulme followed, choosing patience over aggression. Stewart kept third but soon came under pressure from Follmer’s aggressive driving.

The Corkscrew produced early drama. A backmarker spun, nearly collecting Revson. The papaya driver dodged the sliding car by inches. Hulme narrowly avoided the debris. Stewart was not as fortunate, losing several seconds in reflex avoidance.

Mid-race, Revson reasserted control. Hulme stabilized in second. The field behind scattered. Stewart and Follmer ran nose-to-tail. Motschenbacher fought handling imbalance. Dean’s Porsche struggled with Laguna’s elevation changes.

In the final laps, Hulme made a subtle push — but Revson kept him at a comfortable distance. The younger driver had found a new level of composure, and the papaya cars crossed the line nose-to-tail once more.

Revson’s win count rose to six. Hulme’s consistency kept him mathematically alive, but the balance had shifted toward inevitability.

Round 8 — Riverside (October 10, 1971)

Riverside was always a brutaliser — a place where engines cooked, brakes faded, and weak setups were exposed instantly. It was also the second-to-last round of the championship, and the tension between Revson and Hulme had reached its peak.

Qualifying made the stakes clear. Revson on pole. Stewart second. Hulme a distant third — his worst qualifying of the year. His frustration was visible.

The race unfolded with unusual drama. Stewart made an aggressive dive into Turn 1, attempting to steal the lead from Revson. He nearly succeeded — but Revson’s composure held. He defended cleanly and maintained his line.

Hulme, running in third, struggled early with brake temperature. He dropped time to the leaders. Stewart, feeling his best chance all season, hounded Revson until mid-distance, but the Lola’s limitations surfaced again. Over long distances, the M8F simply had more in reserve.

By lap 40, Revson controlled the race. Stewart faded. Hulme stabilized but could not challenge. The field fragmented — the desert heat claiming multiple retirements.

Revson crossed the finish line with one arm extended skyward. The championship was effectively his.

Round 9 — Edmonton (October 24, 1971)

The season finale returned to Edmonton, where the papaya cars had found both triumph and heartbreak in earlier years. But this time, the stakes were simpler: Revson only needed a quiet finish to seal the championship.

He did not choose quiet.

Revson qualified on pole. Hulme second. The rest of the field followed the familiar pattern — Stewart, Follmer, Dean, Eaton.

The race began with Revson charging ahead, determined to win the title with authority. Hulme, characteristically professional, gave chase but made no attempt to disrupt the inevitable. Stewart ran a lonely third.

Midrace attrition again took its toll. The Lola retired with mechanical failure. The Porsche faded. Privateer McLarens circulated steadily but without threat.

Revson held the lead for the full distance, winning by a comfortable margin. Hulme finished second. Follmer third.

Peter Revson was crowned 1971 Canadian-American Challenge Cup Champion.

Epilogue — The End of an Era

The 1971 Can-Am season was the final chapter of McLaren’s original papaya dynasty — the last year of unchallenged supremacy before Porsche’s turbocharged leviathans arrived to rewrite the rulebook.

Peter Revson’s championship marked the culmination of the McLaren vision Bruce had begun: a team built on discipline, precision, and unity. Revson delivered not only results — eight wins in nine races — but a sense of refined execution that carried the tone of a modern McLaren era.

Denny Hulme, the foundation stone of the program, remained the anchor — finishing second in the standings once more, proving that despite injury, age, and shifting team dynamics, his fire never dimmed.

Behind them, the rest of the grid pushed harder than ever before — Stewart’s Lola program, the rising Shadow project, Porsche’s expanding investment, and a legion of privateers gave the season breadth and texture.

But 1971 belonged, wholly and definitively, to the orange cars.

This was the final bloom before the storm.

The last moment of simple papaya rule.

The closing verse of the greatest dynasty in Group 7 history.

Sources:

– Motorsport Magazine Archive — 1971 Can-Am contemporary race reports (Mosport, St. Jovite, Road Atlanta, Mid-Ohio, Road America, Donnybrooke, Laguna Seca, Riverside, Edmonton)

– RacingSportsCars — 1971 Can-Am official results, qualifying sheets, lap charts, and classifications for all nine rounds

– RacingYears — 1971 Can-Am season calendar and final points table

– McLaren Heritage Trust — McLaren M8F development notes, team history, and Revson biography

– Shadow Racing historical archives — DN2 background and 1971 development program

– Porsche racing archives — Porsche 917/10 and 908/03 Can-Am entries and 1971 North American competition history

– Track archives — Mosport Park, Mont-Tremblant, Road Atlanta, Mid-Ohio, Road America, Donnybrooke, Laguna Seca, Riverside, Edmonton (1971 Can-Am event summaries)