Design is Subjective, Taste is Not

The Shape of Time: A History of Automotive Design

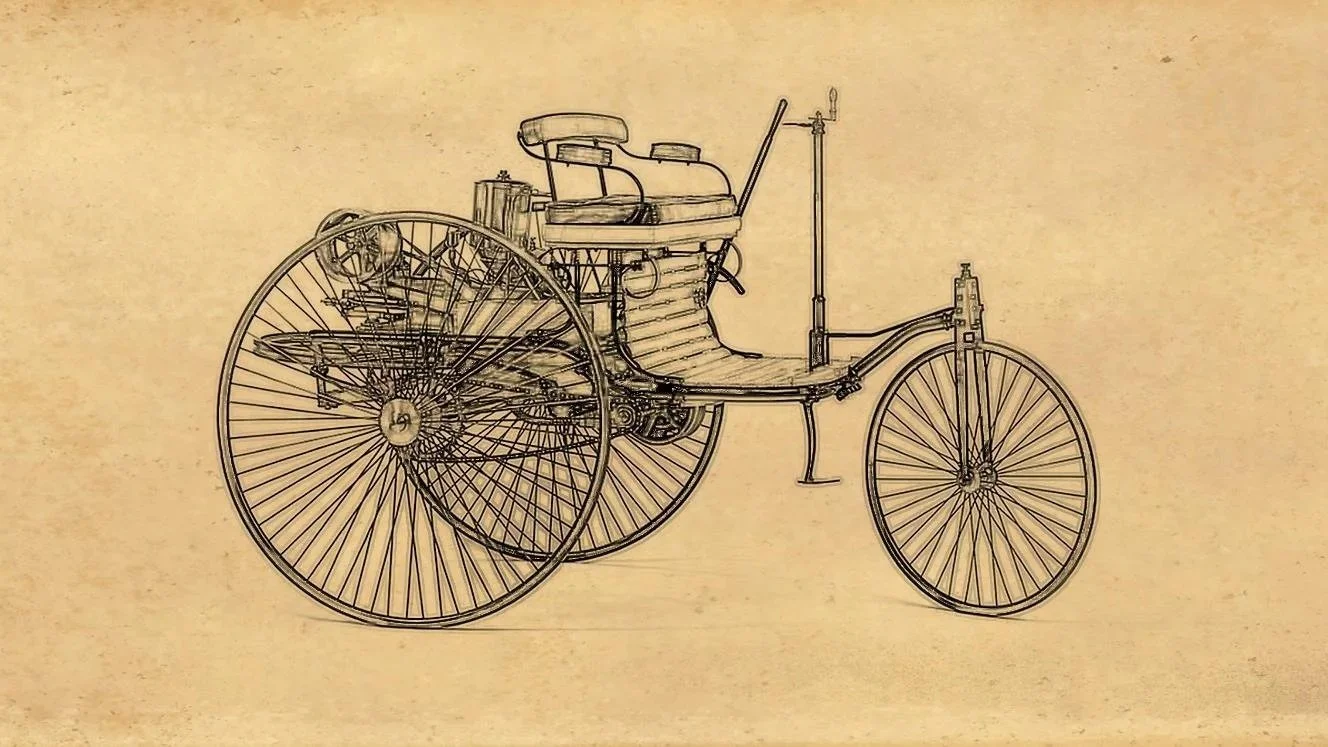

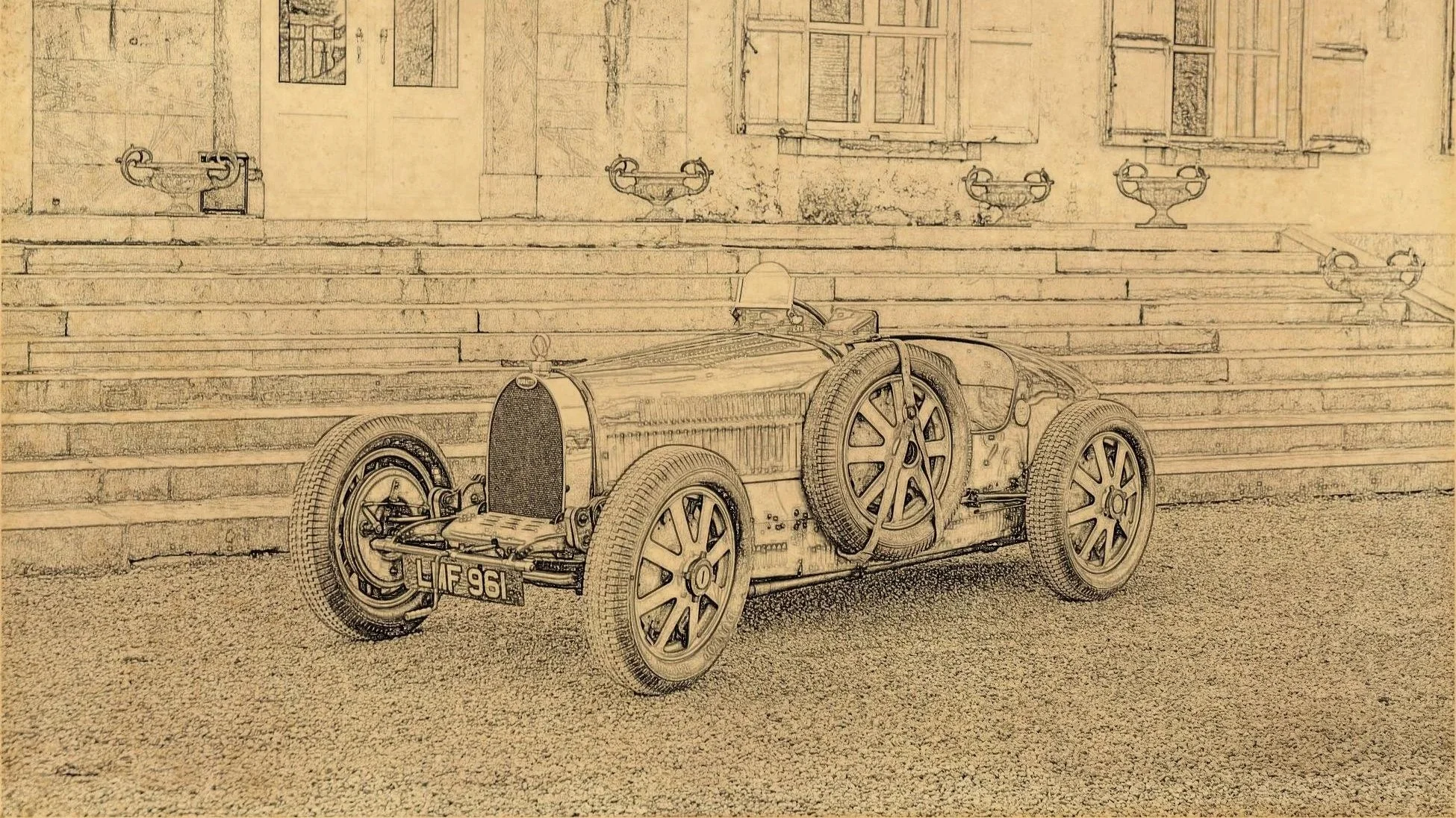

Car design has always mirrored the times; part necessity, part indulgence, and always a reflection of the human imagination. The earliest automobiles were little more than experiments in motion: carriages with engines, crafted by engineers rather than designers. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, pioneers like Karl Benz and Gottlieb Daimler were focused purely on function; creating mechanical contraptions that moved faster and farther than a horse ever could. Their vehicles were upright, spindly, and entirely devoid of artistry, but they were the genesis of something far greater. By the 1910s, men like Ettore Bugatti and Henry Royce began to infuse elegance into engineering. Bugatti believed “a car should be a work of art,” and his Type 35, with its horseshoe grille and impossibly fine proportions, proved that beauty and speed could coexist. The earliest Rolls-Royces, meanwhile, turned refinement itself into a design language; long, stately, and unapologetically luxurious.

Then came the 1920s and 1930s, the age of ornamentation. Function gave way to flair as society, flush with optimism and Art Deco exuberance, demanded glamour. Designers like Harley Earl at General Motors pioneered the very concept of “automotive styling.” He understood that buyers wanted more than transportation; they wanted personality. Under Earl, cars gained sweeping fenders, chrome spears, and sensuous proportions. From the Cadillac V16 to the Buick Y-Job (often called the first concept car), the automobile became rolling jewelry, a symbol of status and self-expression. Meanwhile, in Europe, Jean Bugatti sculpted the Type 57 Atlantic; an impossibly elegant teardrop shape that remains one of the most breathtaking forms ever to wear wheels. Aerodynamics was not yet a science; it was a visual language of speed, crafted by intuition and imagination.

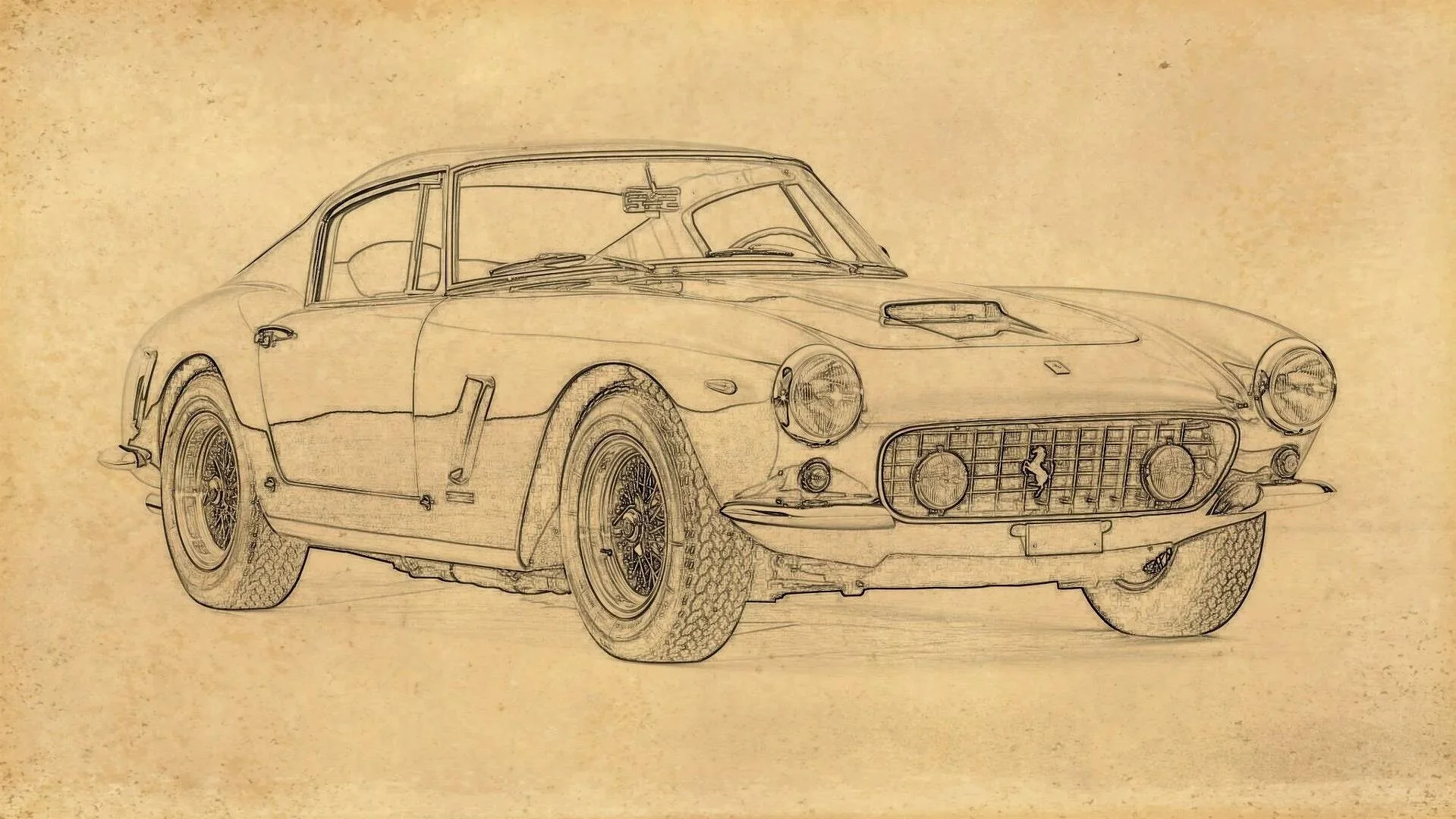

The 1950s brought purpose and futurism, fueled by the jet age and postwar optimism. America looked to the skies, and its cars followed. Designers like Virgil Exner at Chrysler and Bill Mitchell at GM filled showrooms with fins, chrome, and confidence. The Cadillac Eldorado and Chevrolet Bel Air seemed ready to take flight, while the Chrysler 300 combined brutish power with tailored lines. In Italy, a young Giorgetto Giugiaro was beginning his apprenticeship, and Battista “Pinin” Farina’s studio perfected the balance of proportion and purity that defined the Ferrari 250 GT Lusso and Alfa Romeo Giulietta Spider. These cars were mechanical expressions of optimism; rolling sculptures that promised a brighter tomorrow. Even utilitarian cars bore the marks of progress: Citroën’s DS, designed by Flaminio Bertoni and André Lefèbvre, was as revolutionary in its aesthetics as in its technology, fusing futuristic curves with hydraulic wizardry. It looked like it had landed from another planet—and in a way, it had.

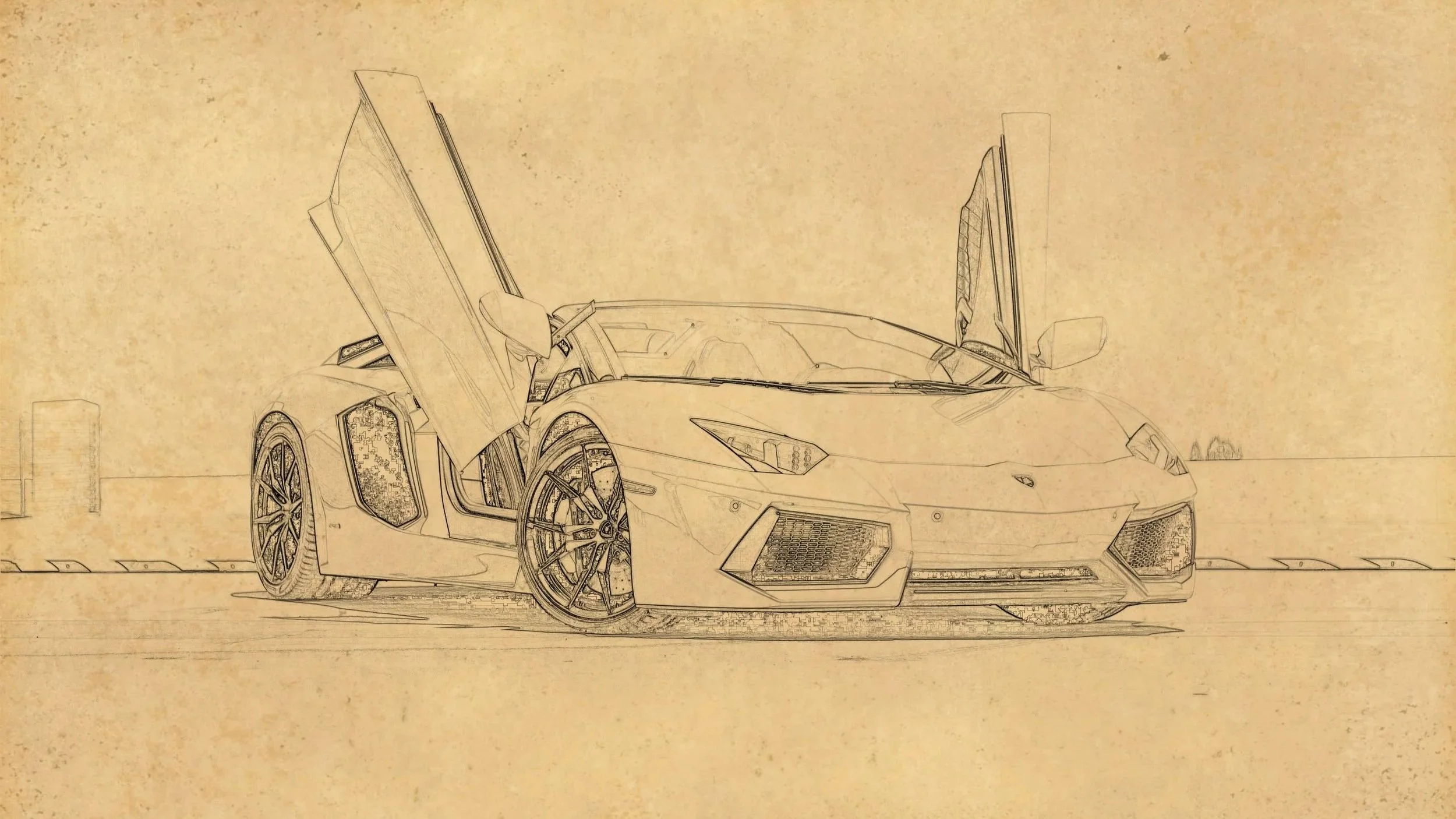

The 1960s brought sensuality. The world was changing; youthful, liberated, adventurous; and the cars of the decade reflected that freedom. The Jaguar E-Type, penned by aerodynamicist Malcolm Sayer, stunned even Enzo Ferrari, who called it “the most beautiful car ever made.” Its long bonnet, curving haunches, and purposeful stance defined an era. In Italy, Marcello Gandini of Bertone introduced the Lamborghini Miura, a car so low and voluptuous it seemed alive. It established the blueprint for every mid-engined supercar that followed. Meanwhile, designers like Sergio Scaglietti shaped the Ferrari 250 GTO; a pure fusion of engineering and art, as functional as it was seductive. In America, Carroll Shelby and Pete Brock turned the AC Cobra and Daytona Coupe into icons of muscle and purpose. These were not just vehicles; they were statements of power, freedom, and individuality.

But the ride was far from steady. The 1970s and 1980s ushered in regulation, crisis, and compromise. The oil embargo, emissions standards, and safety laws forced designers to think within tight constraints. The flamboyance of the ’60s gave way to the “malaise box”: heavy bumpers, bland shapes, and cautionary design. Yet even within these restrictions, brilliance emerged. Giorgetto Giugiaro—now leading Italdesign; mastered the folded-paper aesthetic, giving us the Volkswagen Golf, the Lotus Esprit, and the DeLorean DMC-12. Marcello Gandini countered with the Lamborghini Countach, perhaps the most radical car ever conceived. All wedge and attitude, it ignored softness entirely. Every line was a weapon. The Countach defined the poster generation, proving that rebellion could be beautiful. Across the Atlantic, Ford’s design chief Jack Telnack introduced “aero design” with the 1983 Ford Taurus, showing that even mass-market cars could look futuristic. Meanwhile, Bruno Sacco at Mercedes-Benz pursued “form follows function” with surgical precision, shaping the W126 S-Class and W201 190E into monuments of understated excellence.

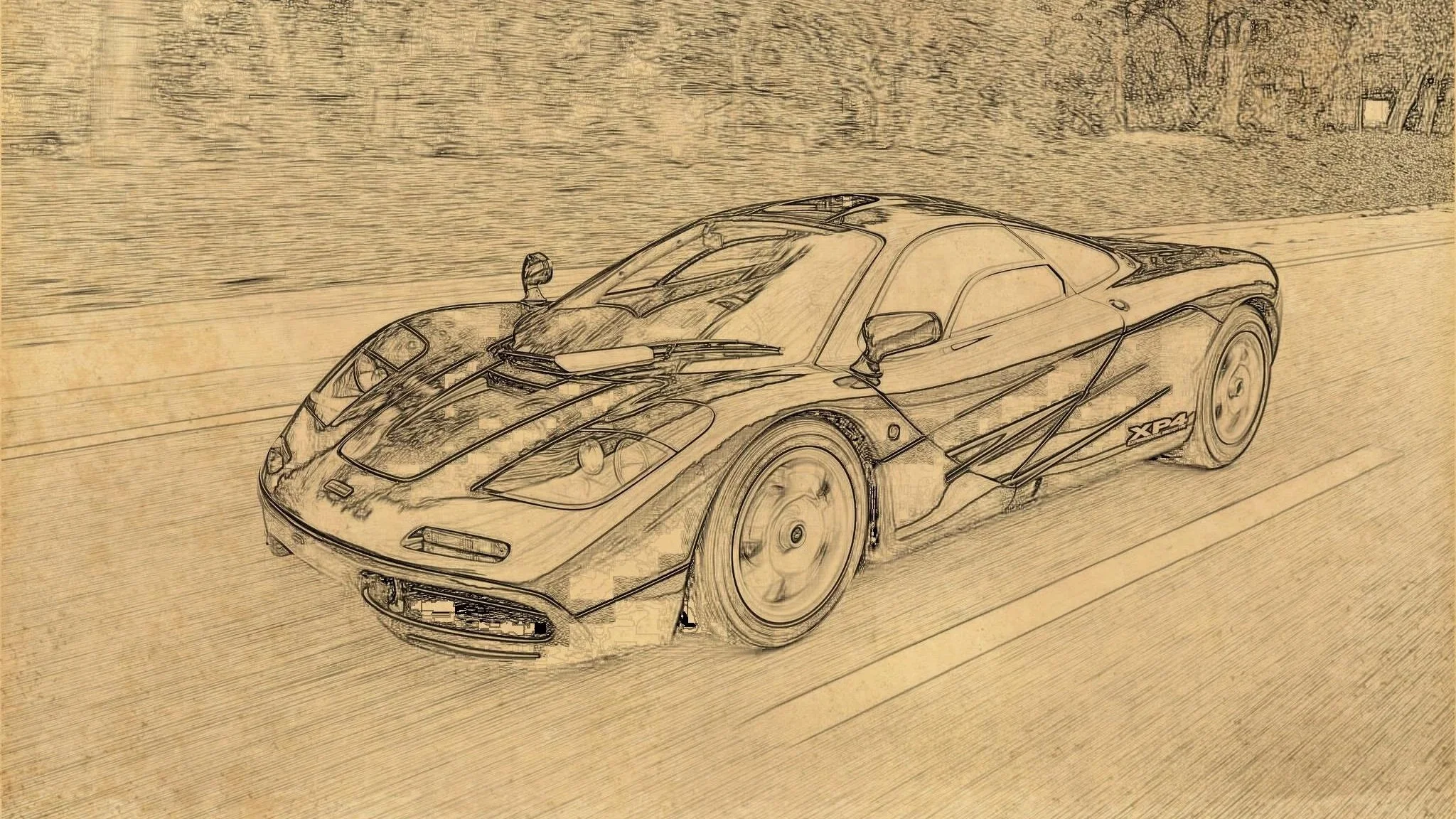

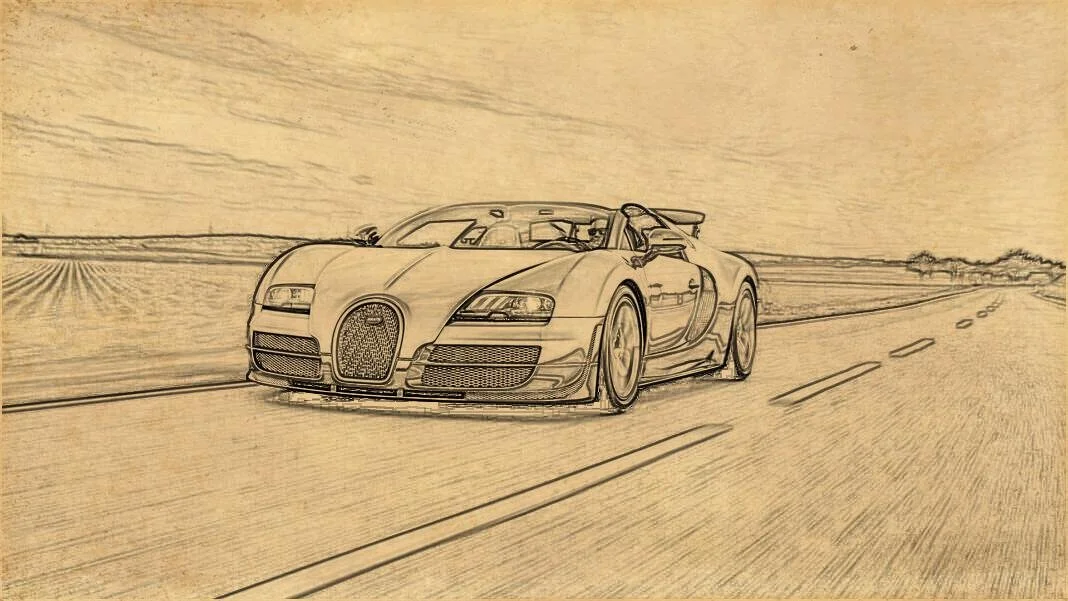

The 1990s, 2000s, and 2010s marked a renaissance; a rediscovery of proportion, purpose, and performance. Design matured; aerodynamics evolved from an art into a science. Gordon Murray’s McLaren F1, designed with minimalist intent, placed the driver at the center and the form around the function. It was not styled to look fast; it was built to be fast. In Italy, Horacio Pagani blended Leonardo da Vinci’s philosophy of art and science, producing the Zonda; a car that looked like an alien sculpture yet exuded craftsmanship and soul. The 1990s also saw the rise of Chris Bangle at BMW, whose “flame surfacing” philosophy redefined how car bodies played with light and shadow; controversial, but influential. In Japan, Shiro Nakamura and designers at Mazda championed “Kodo: Soul of Motion,” crafting cars that felt alive even standing still. The Ferrari F40 and its successor, the Enzo, distilled performance into primal forms, while the Bugatti Veyron pushed technology and luxury into the stratosphere. Every vent, curve, and seam became a dialogue between art and engineering.

And now, in the 2020s, we find ourselves surrounded by softness. Aerodynamics, pedestrian safety, and manufacturing efficiency dictate every line. The once-daring variety of forms has narrowed into a sea of ovoid sameness; smooth, wind-tunnel-optimized “space blobs.” Designers are constrained not by imagination, but by regulation and shareholder caution. Yet brilliance still emerges. Frank Stephenson’s legacy; seen in cars from the McLaren P1 to the modern Mini; proves that emotional proportion can survive even within strict rules. Meanwhile, electric pioneers like Mate Rimac and Tesla’s Franz von Holzhausen have ushered in a new aesthetic: sleek, minimal, but sometimes soulless. The best designs today seek to restore humanity to technology; to balance efficiency with emotion.

Design ebbs and flows like a roller coaster. Yet through it all, one truth remains: every era produces its timeless icons. Some decades simply gave us more of them.

The Anatomy of Timelessness

Every decade delivers striking cars; a more common and easier achievement for many designers. Creating something that transcends time and place is far harder. Most modern shapes stop us in our tracks because they are overdesigned. Too alien, too radical, too bold to ignore. A Lamborghini Revuelto is not pretty; it’s a fighter jet for the road, more intimidating than inspiring. A Pagani Utopia looks less like a car and more like a handcrafted artifact from another civilization. Striking design can overwhelm us, forcing us to reconcile the strange with the spectacular. Where beauty whispers, these machines shout, though often not for as long as their creators might hope.

Timeless design belongs to a different category altogether. A Porsche 356; shaped under Ferry Porsche and Erwin Komenda; is the embodiment of grace and simplicity. Born from the ashes of war, it distilled the dream of mobility into a lightweight, delicate sculpture. Its rounded silhouette wasn’t about excess; it was about restraint. The Jaguar E-Type, designed by Malcolm Sayer and unveiled in 1961, still captures hearts with its perfect balance of proportion and sensuality. The Lamborghini Countach, from the mind of Marcello Gandini, remains as outrageous now as in 1974; its edges as sharp, its attitude as unfiltered as ever. The Ferrari F40, Enzo Ferrari’s final personal project, was pure function rendered in carbon, kevlar, and fire. And the McLaren F1; crafted by Gordon Murray and shaped by Peter Stevens; embodied engineering purity: no gimmicks, no flash, just perfection. Then came the Bugatti Veyron, designed under Jozef Kabaň’s direction; a triumph of engineering excess rendered into sculpture. It didn’t just redefine speed; it redefined how beauty could exist alongside physics.

These cars prove that timelessness isn’t about blending in; it’s about creating a form so resolved and so pure that decades cannot diminish its impact.

Style, Taste, and Legacy

Car design will always be subjective. Some will prefer the flamboyant excess of a finned Cadillac, while others will lean toward the restraint of a Bauhaus-inspired Audi. But timeless design is not a matter of personal preference; it’s a matter of recognition. A truly great car doesn’t just appeal to one person or one generation; it commands respect across decades. We may debate which era produced the most, but we rarely debate which cars belong in the pantheon. That is the difference between style and taste. Trends rise and fade, but a masterpiece announces itself the moment you see it. It resonates on a level beyond words; because it feels inevitable, as though it could never have been shaped any other way.

Why I Write

Why am I qualified to write on this subject? Simply put, cars have been my lifelong obsession. From my earliest memories, I’ve been captivated by their shapes, sounds, and stories. That fascination evolved into discipline; a drive to learn, to sketch, to build. I hold a degree in Industrial Design and Technology from Loughborough University, where I studied the delicate dance between form and function, the ergonomics of the human experience, and the psychology of beauty. My shelves overflow with miniature history: model cars, slot cars, RC builds. Each is a lesson in proportion and storytelling. I design my own cars through CAD and 3D printing, exploring the craft firsthand; learning why some lines sing while others fall flat. And above all, I revere the designers; the Sayers, the Gandinis, the Giugiaros, the Stevens, the Pininfarinas; who shaped our collective imagination.

Car design is a lifelong study, and it’s one I intend to pursue for the rest of my life. I admit my biases freely: some cars move me deeply, and others leave me cold. I believe some brands should be judged more harshly, because heritage demands accountability. A Ferrari must move the soul. A Jaguar must seduce. A Porsche must connect. If a brand betrays its essence, beauty alone cannot save it. Here at Gatsby’s Garage, that’s the standard we’ll uphold.

This site is a dedication to recognizing the truly great designs among the truly forgettable; to giving praise where it’s earned and criticism where it’s due. Cars are art, machines, and mirrors of humanity all at once. And if we’re to celebrate them honestly, we must look at them not just with admiration, but with understanding.

So thank you for being here. Buckle up, and enjoy the ride.

Written October 7th, 2025 by Shane Arun Canekeratne