Indy 500: 1911 - 1916, 1919

The Pioneer Era

1911 Indianapolis 500 — The Birth of the Great American Race

Date: May 30, 1911

Circuit: Indianapolis Motor Speedway (2.5 mi oval, brick surface)

Distance: 500 miles (200 laps)

Entries: 40 starters

Winner: Ray Harroun — Marmon Wasp

Average Speed: 74.602 mph

Prelude to a Legend

In 1911, Carl Fisher—co-founder of the Indianapolis Motor Speedway—sought to elevate American motorsport beyond dusty fairground sprints. His idea: a 500-mile endurance race to test the durability and ingenuity of both car and driver. The “International 500-Mile Sweepstakes” was conceived as a grand technical trial, designed to prove that American engineering could stand against Europe’s best.

The Speedway, newly surfaced with over three million hand-laid bricks, shimmered under the Indiana sun. Manufacturers from both sides of the Atlantic—Marmon, National, Stutz, Fiat, Mercedes, Simplex—entered in force, eager to stake their claim on a $25,000 purse.

The Field and the Machines

Forty cars took the start, nearly all with a driver and riding mechanic—except one. Ray Harroun, a young engineer from the Indianapolis-based Marmon Motor Car Company, chose to drive solo in his bright yellow Marmon Wasp, a narrow-bodied, six-cylinder machine built for both endurance and efficiency.

To compensate for the lack of a riding mechanic, Harroun fitted an experimental rear-view mirror to the car’s cowl—a first in motor racing history. The device caused a stir among competitors, who branded it unsafe and unsporting, but it would become one of the sport’s most enduring inventions.

Race Day

At 10 a.m. on May 30, 1911, an estimated 80,000 spectators filled the grandstands as the 40-car field rolled toward the green flag. Ralph Mulford’s Lozier and David Bruce-Brown’s Fiat were early pacesetters, their engines roaring past the pagoda at over 90 mph.

Harroun, however, kept a methodical rhythm—circulating the 2.5-mile oval at a steady 75 mph, mindful of the punishing brick surface that devoured tires and shattered wheels. As attrition thinned the field, accidents and mechanical failures claimed more than half the entries by mid-race. Charlie Merz’s National crashed heavily near Turn Four, while the European Fiats and Mercedes struggled with cooling issues.

During the sixth hour, Marmon relief driver Cyrus Patschke briefly took over while the car was refueled and re-tired, before handing back to Harroun for the final run to the flag.

The Final Miles

By lap 150, only a dozen cars remained. Mulford’s Lozier continued to chase, but Harroun’s steady pace proved unshakeable. As the final laps unfolded, the Wasp ran flawlessly while Mulford made a late stop for tires and fuel.

After 6 hours and 42 minutes of continuous running, the yellow Marmon Wasp thundered across the line to claim victory—one lap ahead of Mulford’s Lozier. Spectators surged onto the track as Harroun was hailed as both driver and engineer, having conquered 500 miles without a mechanic or major failure.

Aftermath and Legacy

Ray Harroun’s triumph instantly established the Indianapolis 500 as the ultimate test of reliability and innovation. His car’s streamlined tail, single-seat layout, and mirror transformed how engineers thought about both performance and driver awareness.

Harroun retired from racing immediately after the win, returning to engineering with Marmon—content to let his creation speak for him. Mulford protested the result, claiming scoring errors, but officials upheld Harroun’s victory. The Marmon Wasp was retired to history, preserved as an icon of American ingenuity.

The 1911 race laid the foundation for more than a century of Memorial Day tradition, setting a template that still defines the Indianapolis 500 today: speed balanced by endurance, bravery balanced by invention.

Reflections

The inaugural Indianapolis 500 was not simply a race—it was the birth of an idea: that machines and men could prove their worth through distance, discipline, and design. The 1911 event captured America’s industrial optimism, its belief that progress came from courage behind the wheel and cleverness under the hood. Every lap since has been, in essence, a continuation of that first 500-mile dream.

Sources

Indianapolis Motor Speedway Archives — “Official Records of the 1911 International 500-Mile Sweepstakes” (IMS Heritage Collection)

Motorsport Magazine Archive — “Ray Harroun and the Wasp: The First 500” (June 2011 Centennial Edition)

The Indianapolis Star — Contemporary race coverage, May 31, 1911

Firestone Tire & Rubber Company — Technical Report on the 1911 Race Tyres (1912 publication)

Smithsonian Institution — Transportation Collections: “The Marmon Wasp and the Birth of the 500”

1912 Indianapolis 500 — A Victory Earned the Hard Way

Date: May 30, 1912

Circuit: Indianapolis Motor Speedway (2.5 mi oval, brick surface)

Distance: 500 miles (200 laps)

Entries: 24 starters

Winner: Joe Dawson — National Motor Vehicle Company

Average Speed: 78.719 mph

Prelude to the Second Running

The success of the inaugural 1911 race cemented the Indianapolis 500 as a new American institution. Carl Fisher’s dream had proven itself: manufacturers saw the event as both a proving ground and a marketing triumph. Yet the 1912 edition would arrive under a cloud of controversy. Many competitors accused Ray Harroun’s solo victory the year before of violating safety norms, prompting new rules that mandated a two-man team—driver and riding mechanic—for every entry.

In the year since Harroun’s win, the Speedway’s surface had been re-laid and repaired; the roughest bricks were reset, the drainage improved, and the pit lane widened. The race now had official timing and a formal scoring system after complaints from 1911. The focus shifted toward professionalism: endurance and preparation, not experimentation.

The Field and the Machines

Twenty-four cars took the green flag in 1912—a smaller but more serious grid. The National Motor Vehicle Company, based right in Indianapolis, returned determined to avenge its mechanical failures from the previous year. Veteran driver Joe Dawson, just 22 years old, led the effort in a dark blue National powered by a 450-cubic-inch four-cylinder engine, co-driven by riding mechanic Harry Martin.

The European contingent included entries from Fiat and Mercedes, with British driver David Bruce-Brown among the early favorites. American marques Mercer, Stutz, and Simplex completed a field that embodied the country’s blossoming automotive scene—each manufacturer eager to prove reliability over 500 grueling miles.

Race Day

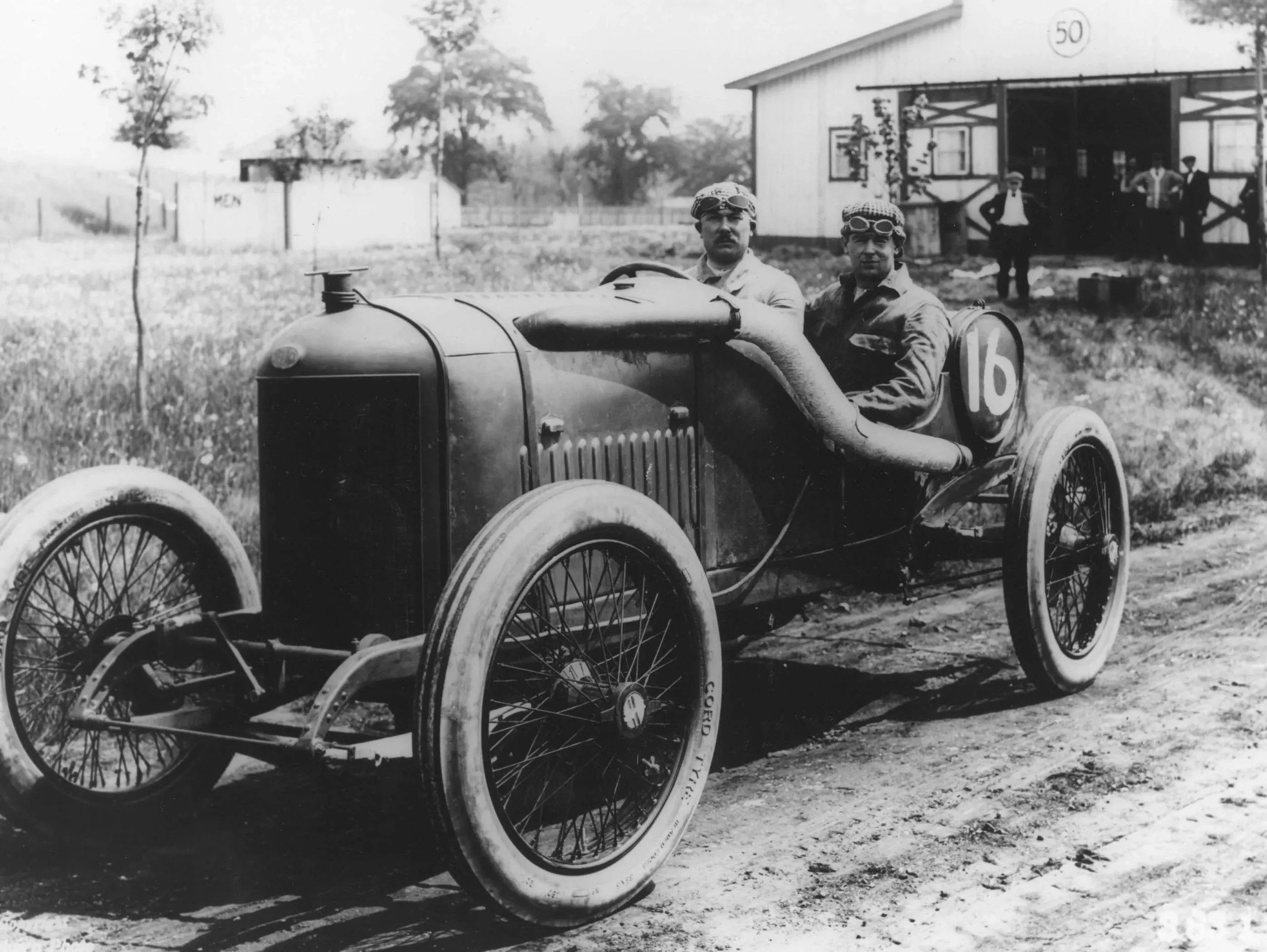

The 1912 race dawned hot and humid. Engines crackled to life before 60,000 spectators as the field took a rolling start behind a Stoddard-Dayton pace car. From the outset, the pace was fierce: Ralph DePalma, driving a massive 14-liter Mercedes Grand Prix, seized control early, lapping the field by the halfway mark. His smooth, consistent driving—averaging nearly 80 mph—made him appear unbeatable.

Meanwhile, Joe Dawson maintained a calculated rhythm in second, content to stay within reach without over-stressing his machine. The brick track, while improved, was still treacherous, and several competitors fell out with engine or tire failures. The fiery Caleb Bragg in a Fiat ran strongly early but suffered mechanical issues by mid-distance.

The Final Miles

For 196 laps, Ralph DePalma and his riding mechanic Rupert Jeffkins dominated the race. Then, heartbreak. With just four laps to go, DePalma’s Mercedes began to sputter, the connecting rod giving way after nearly seven hours of relentless pounding. The white car coasted to a halt on the main straight, only half a lap from the pits.

In one of the most dramatic sights ever witnessed at the Speedway, DePalma and Jeffkins leapt from the stricken Mercedes and pushed it down the straight, trying desperately to complete the distance by hand. The crowd roared in sympathy, but the effort was in vain—the rules required cars to finish under their own power.

As the exhausted Mercedes crawled along the front stretch, Joe Dawson’s National roared past, taking the lead just three laps from the finish. With careful precision, Dawson nursed his car home to win after 6 hours and 21 minutes of running, completing 200 laps at an average of 78.7 mph. The hometown hero had delivered National its greatest triumph on its home track.

Aftermath and Legacy

Joe Dawson’s victory was a story of restraint rewarded. While DePalma’s speed and dominance were unmatched, it was Dawson’s discipline—and the National’s bulletproof reliability—that earned the laurels. DePalma’s gallant push turned defeat into legend, etching his name deeper into Indy folklore than some winners ever achieved.

For National, the win was a pinnacle moment; the company withdrew from racing soon after, content with the prestige of conquering the 500. Dawson himself retired from competition at just 23 years old, one of the youngest winners in Speedway history.

The 1912 race also established key traditions still central to the Indianapolis 500: the endurance of man and machine, the heartbreak of mechanical failure, and the idea that to finish first, one must first finish.

Reflections

If 1911 was about invention, 1912 was about endurance. The second running of the Indianapolis 500 proved that success came not from novelty, but from consistency and courage under pressure. Joe Dawson’s quiet precision contrasted with DePalma’s heroic collapse, setting up one of motorsport’s oldest moral lessons: glory is often earned not by the fastest, but by the last still running.

The image of DePalma and Jeffkins pushing their wounded Mercedes remains one of the most enduring in racing history—a reminder that the Indianapolis 500’s greatest stories are often born not in victory, but in the will to finish.

Sources

Indianapolis Motor Speedway Archives — “Official Records of the 1912 International 500-Mile Sweepstakes” (IMS Heritage Collection)

Motorsport Magazine Archive — “DePalma’s Tragedy: The 1912 Indianapolis 500” (May 1962 retrospective)

The Indianapolis Star — Race-day coverage, May 31, 1912

National Motor Vehicle Company Engineering Notes, 1912 internal race report

Automobile Quarterly, Vol. 8, No. 2 (1970) — “The Men Who Built the 500”

1913 Indianapolis 500 — The First International Victory

Date: May 30, 1913

Circuit: Indianapolis Motor Speedway (2.5 mi oval, brick surface)

Distance: 500 miles (200 laps)

Entries: 27 starters

Winner: Jules Goux — Peugeot

Average Speed: 75.933 mph

Prelude to the Third Running

By 1913, the Indianapolis 500 had matured into a premier test of endurance and engineering. It was no longer an experiment; it was the race every automaker wanted to win. Yet after two American triumphs, Carl Fisher and Speedway officials sought to attract European manufacturers, eager to elevate the contest’s prestige to rival the great Grands Prix of France and Italy.

They succeeded. Peugeot, Delage, Isotta Fraschini, and Sunbeam all crossed the Atlantic, bringing with them cutting-edge technology unseen on American soil. This new European presence transformed the 500 into a global stage—an “international sweepstakes” in the truest sense.

The American faithful, defending their home turf, fielded strong entries from Stutz, Mercer, and National, hoping that local knowledge of the Brickyard’s rough, heat-baked surface would counterbalance European sophistication.

The Field and the Machines

The standout of the foreign contingent was the French Peugeot L76, designed by a brilliant young engineer named Ernest Henry, under the direction of drivers Georges Boillot and Jules Goux. The car’s twin-overhead-camshaft, four-valve engine was revolutionary—an advanced design producing around 130 horsepower from just 7.6 liters. Compared to the lumbering 10- and 14-liter American fours, it was a masterpiece of precision and efficiency.

Jules Goux, a 27-year-old Frenchman from Valentigney and a factory works driver for Peugeot, arrived with calm confidence. His teammate Boillot, delayed by French Grand Prix commitments, left Goux as the sole Peugeot entry at Indianapolis. His riding mechanic, Emile Begin, joined him in the elegant blue-gray racer.

The Americans rallied behind Spencer Wishart (Mercer), Charlie Merz (Stutz), and Bob Burman (Peugeot-built Indianapolis machine), but the writing was on the wall: the Europeans had brought the future with them.

Race Day

Race morning broke bright and warm, with 90,000 spectators packing the Speedway’s wooden grandstands. From the drop of the green flag, Goux’s Peugeot ran like clockwork. The French car’s high revs and smooth power delivery allowed it to run lap after lap without stress, while the American machines pounded themselves to pieces over the rough bricks.

Early pace-setters included Jack Tower in an Alco and Ralph Mulford in a Mercedes, but both fell victim to mechanical troubles before halfway. Goux, meanwhile, drove with European composure—steady, precise, and relentless.

The Peugeot’s advanced suspension and superior fuel economy gave Goux an advantage during the frequent pitstops that defined early Indy races. His only interruptions were for tires and a famously liberal refreshment regimen: according to both French and American press, Goux drank several small glasses of champagne during the race to “keep up his spirits.” The story became legend, though modern historians believe the bubbly was diluted and used as a cooling tonic rather than celebration.

The Final Miles

By lap 160, Goux had lapped the entire field. His nearest challenger, Spencer Wishart’s Mercer, could not match the Peugeot’s pace or reliability. As the race wore on, the European entry maintained its mechanical precision, while the homegrown challengers faltered.

After just over 6 hours and 35 minutes, Jules Goux crossed the finish line to win by 13 minutes and seven laps—one of the most dominant victories in the event’s history. The French flag flew over the Speedway for the first time, signaling a seismic shift in racing technology.

Aftermath and Legacy

Jules Goux’s victory marked the dawn of the European engineering era in Indianapolis. His Peugeot’s twin-cam, four-valve technology became the blueprint for racing engines for decades to come, influencing designs from Miller, Offenhauser, and beyond.

Goux’s triumph also shattered the myth that American toughness could always best European refinement. The Speedway had opened its doors to international innovation, and motorsport would never again be the same.

For Peugeot, the win was both technical validation and global publicity. For America, it was a wake-up call: the future of racing would be forged in precision, not brute force.

Reflections

The 1913 Indianapolis 500 symbolized a turning point—the end of the pioneer years and the beginning of the modern age. In the Peugeot’s smooth hum and flawless rhythm, the world glimpsed the potential of science applied to speed.

Where Dawson and Harroun had triumphed through patience and reliability, Goux conquered through engineering. The era of innovation had truly begun, and the 500 had proven itself a race that could crown not just heroes, but revolutions in design.

Sources

Indianapolis Motor Speedway Archives — “Official Records of the 1913 International 500-Mile Sweepstakes” (IMS Heritage Collection)

Motorsport Magazine Archive — “Peugeot’s Triumph at Indianapolis: The Engine That Changed Racing” (May 2013 Centennial Feature)

The Indianapolis Star, May 31, 1913 — Race-Day and Post-Race Reports

L’Auto, Paris, June 1913 — Correspondence and Technical Notes from the Peugeot Works Team

Automobile Quarterly, Vol. 14, No. 3 (1976) — “The French Invasion: Peugeot at Indy”

Smithsonian Institution, Transportation Collections — Peugeot L76 Technical Drawings

1914 Indianapolis 500 — Europe Dominates Again

Date: May 30, 1914

Circuit: Indianapolis Motor Speedway (2.5 mi oval, brick surface)

Distance: 500 miles (200 laps)

Entries: 30 starters

Winner: René Thomas — Delage (Type Y)

Average Speed: 82.474 mph

Prelude to the Fourth Running

By 1914, the Indianapolis 500 had evolved from an American endurance contest into a full-fledged international spectacle. The previous year’s Peugeot victory had proven that Europe’s engineering prowess could conquer America’s toughest track. This time, the French returned in force—Peugeot, Delage, and Sunbeam among them—determined to defend their supremacy.

The atmosphere was charged with anticipation. Europe stood on the brink of war, though few at Indianapolis realized how soon that shadow would fall. In late May, the world’s finest drivers gathered under clear skies in Indiana, united by speed if only for a fleeting moment.

The Field and the Machines

The 1914 grid was the most sophisticated yet. France brought the latest evolutions of Ernest Henry’s twin-overhead-cam Peugeot engine, now refined to nearly 112 mph on the straights. The Delage Type Y, driven by René Thomas, featured a similar design philosophy but with greater displacement and a more robust crankshaft—an engineering answer to the reliability concerns that had dogged earlier French efforts.

Thomas, a 31-year-old French aviator and racing driver, arrived with quiet focus. His teammate Albert Guyot piloted another Delage, while Jules Goux, the defending champion, returned with a new Peugeot L56.

The Americans countered with homegrown power: Eddie Rickenbacher (Duesenberg-Mason), Barney Oldfield (Stutz), and Spencer Wishart (Mercedes). Yet it was clear from practice that the European designs, smaller in capacity but higher-revving, were years ahead.

Race Day

At 10 a.m. sharp, the field thundered away under the command of starter Fred Wagner’s green flag. The opening laps saw Jules Goux surge into the lead, his Peugeot gliding effortlessly over the bricks. For the first 100 miles, French cars dominated the top five positions, their mechanical harmony contrasting sharply with the raw, booming rhythm of the American fours.

By mid-race, the relentless pace began to take its toll. Tires shredded under the heat; oil leaks and fractured bearings eliminated several contenders. Goux’s Peugeot, leading comfortably, suffered ignition trouble on lap 170, forcing him into a lengthy pit stop. That left René Thomas’s Delage in command, his riding mechanic Robert Leneveu keeping the big four-cylinder running with clockwork precision.

Behind him, Arthur Duray’s Peugeot and Albert Guyot’s second Delage traded positions, but none could match Thomas’s consistency.

The Final Miles

Thomas drove with composure rare for the era. He maintained an 82 mph average—remarkably quick for the brick surface—while managing his car’s fragile tires and fuel load to perfection. Each pit stop was a model of efficiency: tires, oil, fuel, a sip of water, and away.

By the closing laps, the Delage’s exhaust barked sharply with fatigue, but Thomas pressed on. He crossed the line after 6 hours and 21 minutes, seven minutes ahead of Duray’s Peugeot. Guyot finished third, completing an all-French podium. The leading American, Eddie Rickenbacher, could do no better than tenth—a symbolic passing of the torch.

Aftermath and Legacy

René Thomas’s victory gave France its second consecutive Indianapolis 500 win, cementing European technical superiority on American soil. The twin-cam, multi-valve architecture pioneered by Peugeot and refined by Delage became the universal blueprint for racing engines, inspiring Harry Miller’s and later Offenhauser’s American masterpieces.

Delage’s triumph also carried a poetic poignancy: just two months later, Europe would descend into World War I, and the 500 would not see another European factory team for nearly a decade. Many of the men who raced that day—including Thomas himself—would soon trade racing helmets for military uniforms.

Reflections

The 1914 Indianapolis 500 was a final symphony before silence. It represented the peak of the pre-war era, when engineering artistry and international rivalry coexisted in fragile balance. The Delage’s mechanical song, echoing across the bricks, was both a celebration of progress and a prelude to the storm ahead.

Where earlier races had been experiments in endurance, this one was a demonstration of mastery—a race in which Europe’s science defeated America’s strength. It would be eight long years before a Frenchman again returned to claim the Borg-Warner’s spiritual predecessor, but the legacy of 1914’s twin-cam marvels endured across generations.

Sources

Indianapolis Motor Speedway Archives — “Official Records of the 1914 International 500-Mile Sweepstakes” (IMS Heritage Collection)

Motorsport Magazine Archive — “René Thomas and the Final Peace Before War” (May 2014 Centennial Feature)

The Indianapolis Star, May 31, 1914 — Race-day and technical reports

L’Auto, Paris, June 1914 — Correspondence from the Delage and Peugeot teams

Automobile Quarterly, Vol. 19, No. 1 (1981) — “Delage: The Elegance of Engineering”

Smithsonian Institution Transport Collections — Delage Type Y engine documentation

1915 Indianapolis 500 — America Strikes Back

Date: May 31, 1915

Circuit: Indianapolis Motor Speedway (2.5 mi oval, brick surface)

Distance: 500 miles (200 laps)

Entries: 24 starters

Winner: Ralph DePalma — Mercedes

Average Speed: 89.840 mph

Prelude to the Fifth Running

The year 1915 found the world in turmoil. Europe was at war; factories that once built racing cars now built artillery. The great French marques—Peugeot, Delage, and Sunbeam—stayed home, their engineers and drivers called to service. For the first time since 1911, the Indianapolis 500 would be an almost entirely American affair.

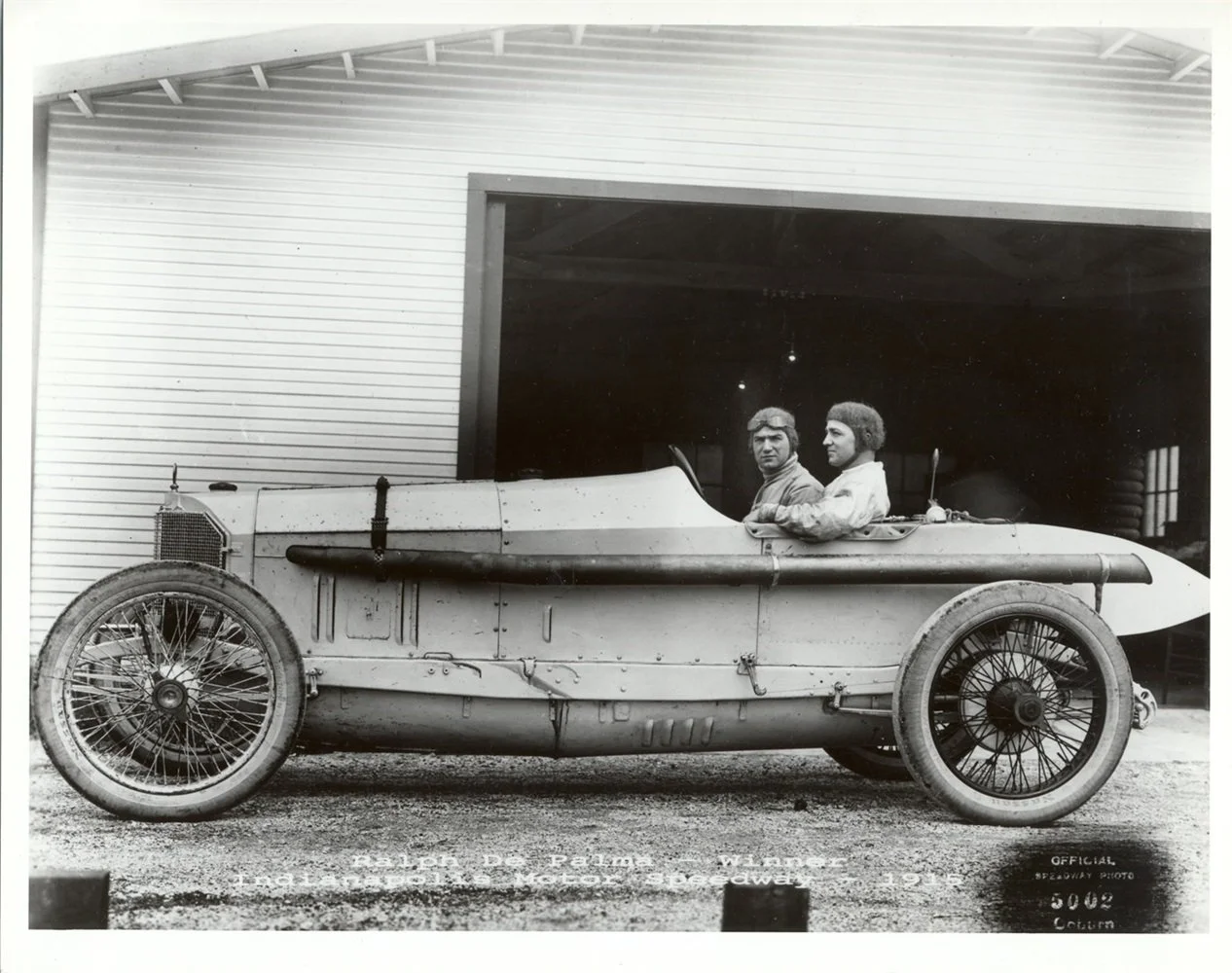

Yet one man bridged both worlds: Ralph DePalma. Born in Italy, raised in the United States, DePalma embodied the international spirit of the early motor age. After his heartbreaking loss in 1912—when his Mercedes failed within sight of victory—he returned three years later determined to finish what he had started.

With much of Europe’s competition absent, 1915 was seen as America’s chance to reclaim its race. But irony would have its way: the car that finally delivered redemption to DePalma, and to Indianapolis itself, was German.

The Field and the Machines

The 1915 entry list reflected both innovation and attrition. The war had slowed production of new designs, so most competitors relied on modified machines from earlier years. The Mercedes GP car, entered privately for DePalma by the New York-based team of Edward Losier, was a proven design from the 1914 French Grand Prix. Its 4.5-liter inline-four produced around 115 horsepower—less than the Peugeots’ peak figures from 1913, but reliable, tractable, and impeccably built.

Against it stood a field of determined American challengers: Duesenberg, Stutz, Delage-Specials, and Maxwells. The Duesenberg brothers entered their new twin-cam racer, while the Indianapolis-built Stutz team fielded its “White Squadron,” fast but fragile.

DePalma’s riding mechanic, Louis Fontaine, joined him once again, sharing both the heat and the haunting memory of their 1912 heartbreak.

Race Day

Memorial Day dawned with perfect conditions—cool, clear, and dry. Twenty-four cars rolled away under Fred Wagner’s flag, their engines echoing across the Speedway’s familiar bricks.

DePalma immediately set the pace, taking the lead before the 20th lap and never truly surrendering it. The Mercedes ran with an elegance unseen since the French entries of 1913–14, its smooth acceleration and stable handling allowing DePalma to lap consistently in the 95 mph range.

Behind him, the Stutz team’s “White Squadron”—piloted by Gil Anderson, Earl Cooper, and Tom Alley—pressed hard, but tire failures and overheating plagued their effort. Duesenberg’s new twin-cam suffered reliability gremlins, leaving DePalma’s white Mercedes unchallenged by mid-distance.

While others broke under the strain, DePalma displayed absolute mechanical sympathy. He timed his fuel and tire stops perfectly, nursing the car’s bearings and brakes through the 500-mile grind.

The Final Miles

By lap 180, DePalma held a lead of over two laps. Ever cautious, he slowed his pace slightly in the closing stages, unwilling to risk a repeat of 1912’s failure. The crowd of 60,000 rose to its feet as the white Mercedes, its engine still singing cleanly, flashed across the bricks after 5 hours, 33 minutes, 55 seconds—an average of 89.840 mph.

At last, redemption. Ralph DePalma had completed the race he once had to push. The image of his 1912 defeat had been erased by a drive of absolute control and endurance.

Aftermath and Legacy

DePalma’s 1915 victory was both personal and symbolic. It was a win for persistence—three years after tragedy—and a reminder of how far engineering reliability had come in a short span. Though Mercedes would soon turn its attention to the war effort, the marque’s performance at Indianapolis solidified its international prestige.

For the United States, the victory marked a turning point. It proved that America could compete with Europe not only in stamina, but in sophistication. The Duesenberg brothers took close notes on Mercedes’ engineering that year—lessons that would later form the foundation of the great Duesenberg straight-eights of the 1920s.

The race also demonstrated the beginning of a more professionalized era of team management, pit coordination, and mechanical preparation. DePalma’s calm, calculated control hinted at the modern driver’s mindset—where victory was achieved through intelligence as much as bravery.

Reflections

The 1915 Indianapolis 500 was a race of closure. For Ralph DePalma, it completed a story begun with heartbreak and ended with redemption. For America, it was a sign that its craftsmen and drivers could match the precision of Europe’s best.

The war in Europe would silence international racing for years to come, but on that clear spring day in Indiana, the Speedway stood as a sanctuary for progress—a place where engines still sang and victory still depended on human endurance.

The brick-paved oval had found its first true master, and the legend of DePalma—the gentleman racer who finished what he started—was immortalized forever in the heart of the Speedway.

Sources

Indianapolis Motor Speedway Archives — “Official Records of the 1915 International 500-Mile Sweepstakes” (IMS Heritage Collection)

Motorsport Magazine Archive — “Ralph DePalma: Redemption at Indianapolis” (May 2015 Centennial Feature)

The Indianapolis Star, June 1, 1915 — Race-day and post-race coverage

Automobile Quarterly, Vol. 12, No. 4 (1974) — “Mercedes at Indy: From Triumph to Silence”

The Horseless Age, June 1915 — Technical review of the Mercedes GP engine

Smithsonian Institution Transportation Archives — Ralph DePalma collection

1916 Indianapolis 500 — The Shortened 500

Date: May 30, 1916

Circuit: Indianapolis Motor Speedway (2.5 mi oval, brick surface)

Distance: 300 miles (120 laps)

Entries: 21 starters

Winner: Dario Resta — Peugeot

Average Speed: 83.257 mph

Prelude to the Sixth Running

The Indianapolis 500 of 1916 stood at a crossroads. Europe was engulfed in World War I, and though America had not yet entered the conflict, the atmosphere of global unease was unmistakable. Automobile manufacturers were tightening budgets, foreign entries had vanished, and the U.S. automotive industry was focusing on practicality rather than spectacle.

Carl Fisher and the Speedway management, mindful of waning entries and growing public fatigue with the long grind of 500 miles, made a controversial decision: the race would be shortened to 300 miles. It was the first—and remains the only—time in the event’s history that the “500” name did not match the distance.

Despite skepticism from purists, Fisher argued the change would make the event more exciting, less grueling on machines, and more digestible for spectators. In hindsight, the 1916 race became a fascinating anomaly—a compressed, high-speed snapshot of an era about to be interrupted by war.

The Field and the Machines

With the European marques gone, the field was distinctly American, though one familiar French design remained: Peugeot. The French-built L56s, now privately owned and maintained in the United States, had been purchased by American teams and engineers who recognized their technical brilliance. Chief among them was Dario Resta, a British-born Italian driver racing for the Peugeot team run by Alphonse Kaufman, using the same twin-overhead-cam, four-valve engines that had revolutionized racing three years prior.

Resta, already a star of the American racing scene, had finished second at Indy in 1915. He returned as favorite, piloting a meticulously prepared Peugeot fitted with improved Firestone tires and a refined fuel system. His rivals included Johnny Aitken (Indianapolis-built Peugeot), Ralph DePalma (Mercedes), and Eddie Rickenbacher, the young American talent soon destined for wartime heroics.

Race Day

Under perfect blue skies and a crowd of roughly 35,000 spectators—smaller than prior years but still enthusiastic—the 1916 race began at 10 a.m. with a rolling start. The shorter distance turned the contest into an outright sprint: pit strategy was minimal, and there would be no relief drivers or extended repairs.

Dario Resta immediately took command, leading 103 of the 120 laps with near-total dominance. His Peugeot’s precision and speed were unmatched; its DOHC four-cylinder ran faultlessly, revving to nearly 3,000 rpm while maintaining steady oil pressure. Johnny Aitken, in the sister Peugeot, shadowed him early but faded with mechanical issues. Ralph DePalma’s Mercedes, still potent but aging, suffered tire wear that forced repeated pit stops.

The only major challenge came from Ralph Mulford’s Duesenberg, whose light chassis and efficient engine allowed him to momentarily close the gap during mid-race traffic. But Resta’s smooth control and mechanical sympathy ensured his lead remained unthreatened.

The Final Miles

At 300 miles, after just 3 hours and 2 minutes, Dario Resta crossed the line in front of the grandstands, averaging 83.257 mph—a blistering pace for the era. His Peugeot had run flawlessly from start to finish, while Mulford finished second and DePalma third, completing a podium that represented the old guard of early American racing.

The crowd cheered, but the truncated distance left some uneasy. While the racing had been intense, many felt that the true challenge of the Indianapolis 500 lay in endurance—and that had been sacrificed. Still, in an uncertain world, the spectacle had survived, and for Fisher, that alone justified the experiment.

Aftermath and Legacy

Dario Resta’s victory made him the first British-born winner of the Indianapolis 500, though he won in an American-owned French car—a fitting symbol of the cosmopolitan early era of motor racing. His drive was a display of mechanical intelligence and smooth precision, hallmarks that would define professional racing in the years ahead.

The 1916 race also marked a transition: the last pre-war running of the Indianapolis 500. Within a year, America would enter the Great War, and the Speedway would fall silent. No race would be held in 1917 or 1918, the circuit instead serving as a military aviation repair depot.

When racing returned in 1919, the “500” would be restored to its full distance, and the short-lived 300-mile experiment would become a historical curiosity. But in its brief, intense burst of speed, the 1916 event captured the essence of an era closing—fast, fragile, and fleeting.

Reflections

The 1916 Indianapolis 500 was a race defined by its contradictions: shorter yet faster, smaller yet sharper, and overshadowed by a world in conflict. Dario Resta’s victory was not just a triumph of driving skill—it was a symbol of endurance in uncertain times.

Though the race lacked the full 500-mile mystique, it represented resilience. The Speedway had survived through adaptation, and its champions—like Resta—embodied the blend of artistry and precision that would define racing in the century to come.

Sources

Indianapolis Motor Speedway Archives — “Official Records of the 1916 International 300-Mile Sweepstakes” (IMS Heritage Collection)

Motorsport Magazine Archive — “Dario Resta and the Shortened 500” (May 2016 Centennial Feature)

The Indianapolis Star, May 31, 1916 — Race-day and technical coverage

Automobile Quarterly, Vol. 15, No. 2 (1977) — “The War Years: Racing in Transition”

Firestone Tire Company Historical Papers — “Performance Analysis: 1916 Indianapolis Tires”

Smithsonian Institution — Automotive Division: Peugeot L56 Engine Documentation

1919 Indianapolis 500 — The Return to Racing

Date: May 31, 1919

Circuit: Indianapolis Motor Speedway (2.5 mi oval, brick surface)

Distance: 500 miles (200 laps)

Entries: 33 starters

Winner: Howdy Wilcox — Peugeot (Indianapolis Motor Speedway Team)

Average Speed: 88.05 mph

Prelude to the Seventh Running

When the engines finally roared again at Indianapolis in 1919, it had been three long years since the last “500.” The First World War had silenced the Speedway, which served during the conflict as a military aviation repair depot known as the “Speedway Aviation Repair Station.” Now, with peace restored, Carl Fisher and James Allison reopened the track as both a monument to progress and a symbol of renewal.

The war had changed everything. Many pre-war champions—Dario Resta, René Thomas, and Jules Goux—remained in Europe. Others, like Eddie Rickenbacher, returned as decorated aviators rather than drivers. But racing’s spirit endured. The 1919 Indianapolis 500 stood not only as a sporting event, but as a celebration of resilience—a triumphant return to motion after years of stillness.

The Field and the Machines

The post-war field blended survivors and newcomers. The powerful Peugeots, which had dominated before the war, now ran under American management. Their twin-cam, four-valve engines had been reverse-engineered by several American engineers during the war years—chief among them Harry Miller, who would soon reshape American racing forever.

Driving one of these Peugeots was Howard “Howdy” Wilcox, a smooth and experienced Indianapolis native who had served as a test driver during the Speedway’s early years. His machine, prepared by the Indianapolis Motor Speedway team and managed by legendary engineer Leo Goossen, was considered one of the most balanced entries on the grid.

Other notable contenders included Jules Goux (Peugeot, returning from France), Ralph DePalma (Packard V12), and Louis Chevrolet (Frontenac). The field was deep, diverse, and hungry to race again.

Race Day

The morning of May 31, 1919, dawned clear and cool. Over 100,000 spectators—many veterans still in uniform—filled the grandstands, eager to witness the rebirth of the 500. Fred Wagner once again dropped the green flag, sending 33 cars thundering down the brick straightaway for the first post-war running of America’s greatest race.

From the start, Ralph DePalma asserted himself in the Packard 299, a V12-powered behemoth with staggering straight-line speed. DePalma led much of the early going, his Packard lapping the field before half-distance. But reliability, as so often before, proved his undoing. Just after the 300-mile mark, a connecting rod failed, forcing DePalma to retire—his second great heartbreak at Indianapolis.

That opened the door for Howdy Wilcox, who had been running steadily in the top three all day. His Peugeot, smoother and more efficient, took command and never looked back. Behind him, Goux and Eddie Hearne (also in a Peugeot) chased but couldn’t close the gap.

The Final Miles

Wilcox maintained a perfect balance between speed and caution, conserving his car as others faltered. By the final 50 miles, he held a comfortable two-lap lead. As the sun began to dip over the pagoda, the Indianapolis crowd rose in applause as their hometown driver crossed the line to take the checkered flag after 5 hours, 44 minutes, and 21 seconds.

His average speed—88.05 mph—was remarkable given the age of the Peugeot and the track’s rough post-war surface. Goux finished second, and Hearne third, completing a Peugeot sweep of the podium.

Aftermath and Legacy

The 1919 Indianapolis 500 was more than a race—it was a resurrection. It reestablished the Speedway as America’s premier racing venue and introduced a new generation of engineers to the principles that would define the 1920s. The Peugeot’s engine design, refined by Goossen and Miller, would evolve into the legendary Miller and Offenhauser engines that would dominate for decades.

For Howdy Wilcox, the victory was career-defining. The soft-spoken Indianapolis native became a symbol of local pride, embodying the rebirth of the Speedway and the optimism of post-war America.

The 1919 event also set the stage for the next golden era of innovation. In the years to come, new materials, forced induction, and streamlined bodywork would transform the 500 into a technological battleground once again.

Reflections

The 1919 Indianapolis 500 captured a nation ready to move forward. Its return symbolized more than the revival of sport—it marked the restoration of motion itself, of invention, of ambition.

Wilcox’s calm drive in a war-weathered Peugeot served as both an ending and a beginning: the close of the heroic pre-war age, and the quiet dawn of America’s engineering ascendancy. The race proved that even after global turmoil, the hum of engines and the quest for speed could unite people once again under the same timeless sound—the echo of progress over brick and time.

Sources

Indianapolis Motor Speedway Archives — “Official Records of the 1919 International 500-Mile Sweepstakes” (IMS Heritage Collection)

Motorsport Magazine Archive — “The Return of the 500: Howdy Wilcox and the Postwar Revival” (May 2019 Centennial Feature)

The Indianapolis Star, June 1, 1919 — Race-day and victory coverage

Automobile Quarterly, Vol. 20, No. 3 (1982) — “The Rebirth of the Brickyard”

Firestone Tire & Rubber Co. Report, 1919 — “Postwar Tire Development for Racing Applications”

Smithsonian Institution — Transportation Collections: Peugeot & Miller Engine Design Papers