Indy 500: 1920 - 1941

The Factory and Front-Drive Era

1920 Indianapolis 500 — The Rise of the Frontenacs

Date: May 31, 1920

Circuit: Indianapolis Motor Speedway (2.5 mi oval, brick surface)

Distance: 500 miles (200 laps)

Entries: 23 starters

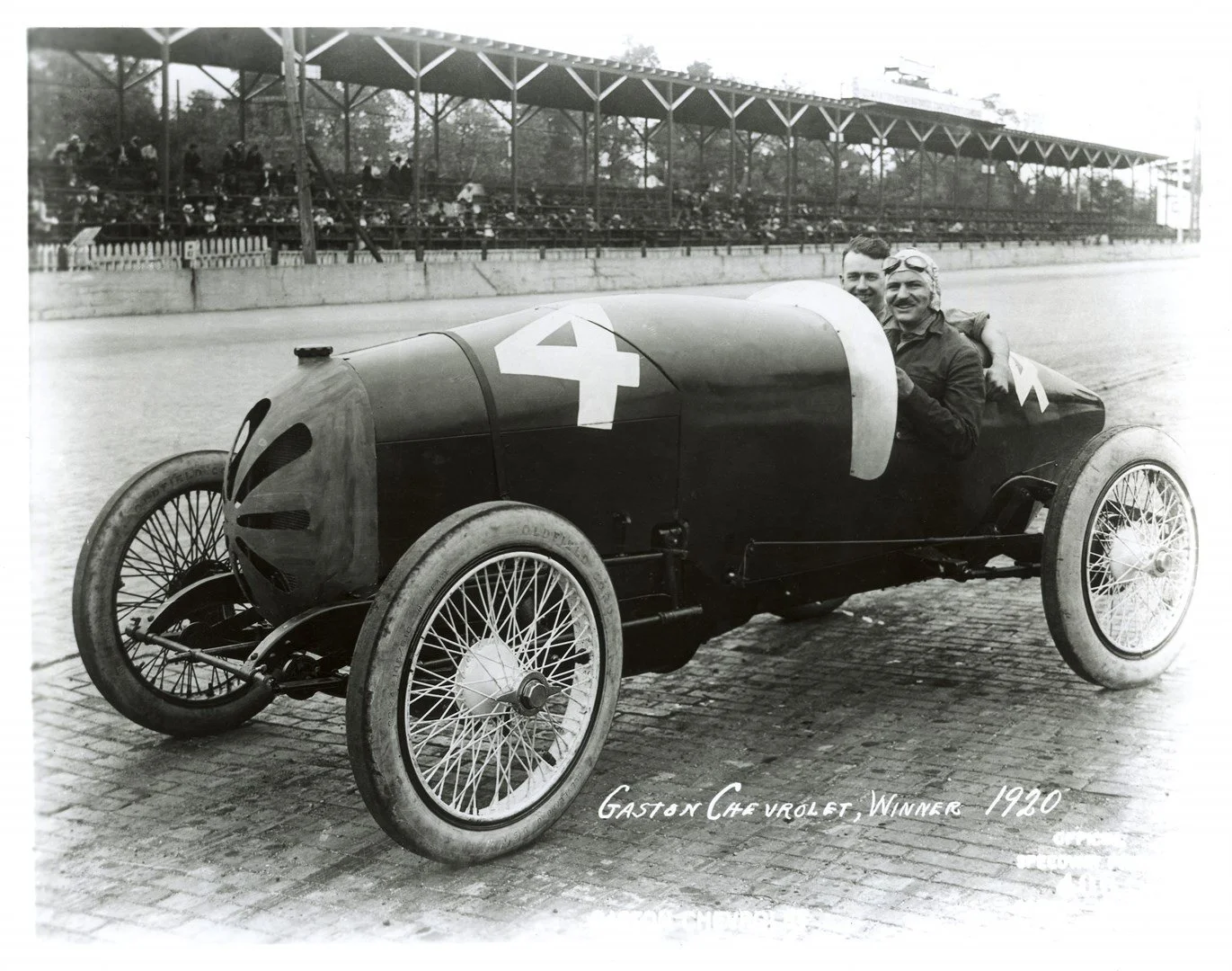

Winner: Gaston Chevrolet — Monroe-Frontenac

Average Speed: 88.618 mph

Prelude to the Roaring Twenties

The 1920 Indianapolis 500 marked not only a new decade but a new direction for American motorsport. The war years had elevated engineering capability across the United States—aircraft, metallurgy, and precision machining had all advanced rapidly—and the Speedway became the perfect stage to showcase this technological maturity.

Gone were the European works teams that once dominated. In their place, a new breed of American constructors—Harry Miller, Louis Chevrolet, and Fred Duesenberg—brought innovation and pride to a field that was now entirely domestic.

For the Chevrolet brothers, who had already left General Motors and pursued independent racing dreams, the 1920 race represented a deeply personal mission. Their small Frontenac operation, based in Detroit, fielded several cars powered by lightweight, high-compression four-cylinder engines—a design that promised both efficiency and durability.

Leading the charge was Gaston Chevrolet, the youngest of the three brothers, known for his smooth precision and quiet determination.

The Field and the Machines

The 1920 entry list was smaller but fiercely competitive. The once-mighty Peugeots were now privately entered relics, their influence living on in Miller’s newly designed twin-cam engines. The Frontenac team, run by Louis Chevrolet, entered multiple cars under the Monroe and Frontenac banners, distinguished primarily by sponsorship rather than mechanical difference.

Gaston Chevrolet piloted the No. 4 Monroe-Frontenac, powered by a 183-cubic-inch straight-four producing roughly 120 horsepower. Its compact aluminum block and overhead valves gave it an edge in efficiency and handling.

Other challengers included Ralph DePalma in a 12-cylinder Packard 299, Tommy Milton in a Duesenberg, and Jimmy Murphy—soon to become one of America’s first true racing stars.

Race Day

Under bright skies and before nearly 75,000 spectators, the field rolled off for the start of the 8th Indianapolis 500. From the outset, Ralph DePalma once again looked untouchable. His Packard V12 surged into an early lead, lapping the field within 150 miles. His pace was relentless—fast enough to set records, but punishing to the car.

Behind him, Gaston Chevrolet drove with careful restraint. The Monroe’s lighter weight and gentle fuel consumption allowed longer stints between stops. By lap 175, DePalma’s Packard began to falter—bearing issues and overheating robbed it of speed. On lap 187, the car finally coasted to a halt, echoing DePalma’s familiar heartbreaks of 1912 and 1919.

Chevrolet inherited the lead and never relinquished it. Smooth, consistent, and mistake-free, he kept the Monroe at a steady 90 mph pace, completing the distance in 5 hours, 40 minutes, 42 seconds.

The Final Miles

As the checkered flag fell, the grandstands erupted. Gaston Chevrolet had achieved a historic milestone: the first driver to complete the Indianapolis 500 without a single tire change. His Goodyear tires had lasted the full 500 miles—a testament to both mechanical gentleness and the new standard of durability emerging in American motorsport.

René Thomas (Delage) finished second, and Tommy Milton (Duesenberg) came third, giving the race a balanced mix of old-world experience and new-world innovation.

Aftermath and Legacy

Gaston Chevrolet’s victory symbolized the coming of age of American design. The Frontenac’s engineering reflected the evolution of the Peugeot school of thought—compact, high-revving, and precise—but adapted with distinctly American pragmatism.

Tragically, Chevrolet’s triumph would be his last. Later that same year, he was killed in a crash during a race at Beverly Hills Speedway, ending the Chevrolet brothers’ shared racing dream on a somber note. His legacy, however, endured through the influence of Frontenac and the rise of Miller’s next generation of engines.

The 1920 race also represented a cultural shift: the dawn of the “Roaring Twenties,” when speed became a national obsession and the Indianapolis 500 stood as its annual proving ground.

Reflections

The 1920 Indianapolis 500 was a race of transition—from endurance to precision, from imported ingenuity to American innovation. Gaston Chevrolet’s win closed one chapter and began another: the era of U.S. engineering dominance that would define the next two decades of the Speedway.

In the echo of his engine and the unbroken hum of his tires, the 500 entered the modern age—an age of lightness, efficiency, and relentless progress.

Sources

Indianapolis Motor Speedway Archives — “Official Records of the 1920 International 500-Mile Sweepstakes” (IMS Heritage Collection)

Motorsport Magazine Archive — “Gaston Chevrolet and the Rise of Frontenac” (May 2020 Centennial Feature)

The Indianapolis Star, June 1, 1920 — Race-day and technical coverage

Automobile Quarterly, Vol. 24, No. 2 (1986) — “Frontenac and the Birth of American Racing Engineering”

Goodyear Tire & Rubber Co. Technical Report — “Tire Endurance at the 1920 Indianapolis 500”

Smithsonian Institution Transportation Archives — Chevrolet-Frontenac Engineering Drawings

1921 Indianapolis 500 — The Dawn of a New Age

Date: May 30, 1921

Circuit: Indianapolis Motor Speedway (2.5 mi oval, brick surface)

Distance: 500 miles (200 laps)

Entries: 23 starters

Winner: Tommy Milton — Frontenac

Average Speed: 89.621 mph

Prelude to the Ninth Running

The 1921 Indianapolis 500 marked the final transition from the pioneering brass-era races into a modern, technical age. The Speedway had survived war, economic uncertainty, and shifting priorities, emerging as the crown jewel of American motorsport.

The tragic death of Gaston Chevrolet late in 1920 still loomed over the paddock. His victory the year before had proven the brilliance of American engineering—especially that of the Chevrolet brothers’ Frontenac concern—and now Tommy Milton, one of the most talented and analytical drivers of his generation, stepped forward to carry that torch.

It was also the last time before a long hiatus that European manufacturers would appear in earnest. Ballot, the French marque with its Grand Prix pedigree, arrived with factory entries for Jules Goux and Jean Chassagne, bringing cutting-edge four-cylinder designs. Across the paddock, the Frontenac and Duesenberg teams prepared to defend America’s honor on home soil.

The Field and the Machines

The Frontenac Type 21, developed from the earlier Chevrolet-Frontenac design, was a light, compact machine powered by a 183-cubic-inch inline-four. It produced around 125 horsepower and featured twin overhead camshafts—a clear evolution of the Peugeot lineage but refined for durability and American fuel quality.

Tommy Milton, a quiet perfectionist known for his mechanical empathy, led the Frontenac works team. His main rivals included Ralph DePalma, back with a Packard straight-eight; Jimmy Murphy, in a Duesenberg; and the Frenchmen Goux and Chassagne in their beautifully prepared Ballots.

The stage was set for a transatlantic duel: French precision versus American practicality.

Race Day

Under clear skies and a warm Indiana breeze, 23 cars lined up on the bricks for the ninth running of the Indianapolis 500. When Fred Wagner’s green flag dropped, Ralph DePalma again surged into the lead—his familiar combination of speed and misfortune making him the crowd favorite.

DePalma’s Packard dominated the early laps, setting a blistering pace that strained its tires and fuel. Meanwhile, Tommy Milton, patient as ever, ran a carefully calculated rhythm in second place, conserving both his car and his energy.

By the halfway mark, the Packard’s relentless pace caught up with it: overheating and tire issues forced DePalma into multiple pit stops. The Ballots of Goux and Chassagne threatened early but faded with ignition problems, their complex European magnetos proving fragile in the heat.

At 350 miles, Milton took the lead and never relinquished it. His Frontenac’s consistent pace, smooth handling, and reliable Goodyear tires carried him through as rivals broke one by one.

The Final Miles

With 50 laps remaining, Roscoe Sarles, Milton’s teammate in another Frontenac, briefly closed the gap, but team orders and fatigue kept Milton ahead. As the hours wore on, the race became a test of mechanical survival.

After 5 hours, 35 minutes, and 40 seconds, Tommy Milton crossed the line to claim his first Indianapolis 500 victory—averaging 89.621 mph. Sarles finished second, sealing a Frontenac one-two finish and the second consecutive win for Chevrolet engineering. Ralph DePalma, ever the heartbreak story, came home third.

Aftermath and Legacy

Tommy Milton’s 1921 triumph was a defining moment in the evolution of the Indianapolis 500. It marked the end of the Frontenac era—the last win for the Chevrolet brothers’ team before it was dissolved—and the beginning of the American engineering boom that would dominate the 1920s.

Milton’s disciplined approach symbolized the maturing mindset of the professional racing driver. No longer were victories achieved through sheer daring alone; now they demanded mechanical understanding, restraint, and strategic intelligence.

The race also marked the twilight of European participation. With Ballot’s withdrawal and Europe still recovering economically from the war, the next decade would belong fully to American innovation.

For Tommy Milton, the win was career-defining. He would go on to take a second Indianapolis 500 victory in 1923, cementing his reputation as one of the Speedway’s most cerebral and consistent champions.

Reflections

The 1921 Indianapolis 500 was a symbolic changing of the guard. It bridged the romantic, dangerous early years and the disciplined, engineering-led modern era. Milton’s smooth, unflappable drive embodied the race’s evolution—from endurance contest to calculated, high-speed science.

Frontenac’s victory closed the Chevrolet brothers’ chapter at Indianapolis, but their influence lived on. Their pursuit of lightness, precision, and efficiency paved the way for the rise of Harry Miller and, eventually, the Offenhauser dynasty that would rule for half a century.

In 1921, the bricks of Indianapolis echoed not with brute force, but with the hum of progress—a sign that racing’s future had truly arrived.

Sources

Indianapolis Motor Speedway Archives — “Official Records of the 1921 International 500-Mile Sweepstakes” (IMS Heritage Collection)

Motorsport Magazine Archive — “Tommy Milton and the End of the Frontenac Era” (May 2021 Centennial Feature)

The Indianapolis Star, May 31–June 1, 1921 — Race coverage and technical notes

Automobile Quarterly, Vol. 25, No. 3 (1987) — “Milton’s Mind: The First Technical Driver”

Goodyear Tire & Rubber Co. Historical Report — “Tire Durability Data: 1921 Indianapolis Race”

Smithsonian Institution — Automotive Division: Frontenac Type 21 Engine Documentation

1922 Indianapolis 500 — The First All-American Victory

Date: May 30, 1922

Circuit: Indianapolis Motor Speedway (2.5 mi oval, brick surface)

Distance: 500 miles (200 laps)

Entries: 27 starters

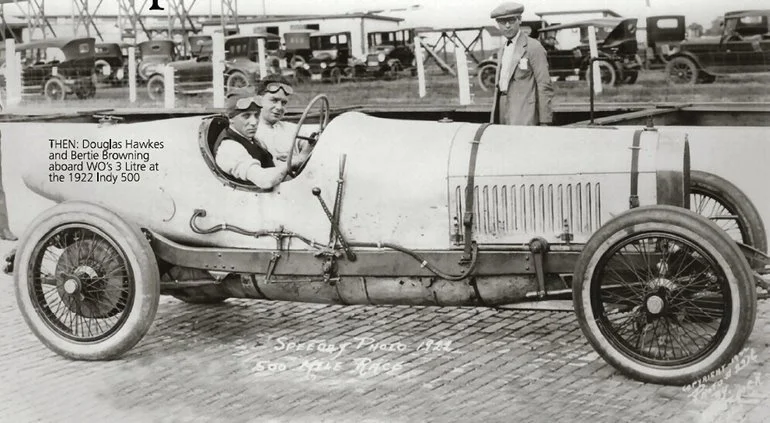

Winner: Jimmy Murphy — Duesenberg Straight Eight

Average Speed: 94.484 mph

Prelude to the Tenth Running

By 1922, the Indianapolis 500 had matured into both a technical and national institution. Gone were the days of foreign factories and experimental machines—the post-war American auto industry had fully taken command. The war had accelerated mechanical understanding, and for the first time, an American-built car, engine, and driver would stand on even footing with anything the Europeans had once produced.

That moment arrived in the form of Duesenberg—a small Indianapolis-based marque founded by brothers Fred and August Duesenberg, whose obsession with precision engineering mirrored the meticulous craftsmanship once associated with France’s Peugeot. Their latest creation, the Duesenberg Straight Eight, represented a leap forward: lightweight, twin-overhead-cam, four-valve technology built entirely on American soil.

Behind the wheel was James “Jimmy” Murphy, a California-born racer who had spent 1921 driving for Duesenberg in Europe, where he famously won the French Grand Prix at Le Mans—the first American to do so. Now he returned home, determined to add the Indianapolis 500 to his résumé.

The Field and the Machines

The 1922 field was stacked with American ingenuity. Duesenberg, Frontenac, and Miller engines dominated the entry list, while Harry Miller’s newly designed straight-eight was beginning to appear in privateer hands.

Jimmy Murphy’s car, a No. 12 Duesenberg, used a 183 cu in (3.0 L) straight-eight engine producing around 150 horsepower—both powerful and efficient. The chassis was light, the handling superb, and its reliability unmatched.

Key challengers included Harry Hartz (Duesenberg), Tommy Milton (Miller-Frontenac), and Ralph DePalma, still chasing the elusive second win that fate so often denied him.

Race Day

Under perfect blue skies and before a crowd exceeding 100,000, the tenth running of the Indianapolis 500 began at 10 a.m. Fred Wagner’s green flag unleashed 27 machines onto the shimmering bricks.

Ralph DePalma again charged into the early lead, his Packard’s twelve cylinders roaring down the straights. For the first 50 laps, the race appeared to follow its familiar script—DePalma dominant, with Murphy shadowing patiently behind.

Then, as the temperature climbed, DePalma’s car began to overheat. At lap 102, a broken connecting rod ended his day. Seizing the opportunity, Murphy took command, setting a blistering pace that averaged over 94 mph—unheard of for the era.

Pitwork proved decisive. Duesenberg’s crew executed fast, disciplined stops, refueling and changing tires in record time. Murphy drove with mechanical sympathy, managing both tires and revs with the ease of a veteran.

The Final Miles

By the final 50 laps, Murphy held a full lap lead over Harry Hartz and Bennett Hill. His Duesenberg ran faultlessly—its engine note constant, its handling crisp even on the rough bricks. Spectators sensed they were witnessing something special: a home-built car dominating its European-inspired predecessors through precision rather than brute force.

After 5 hours, 17 minutes, 30 seconds, Jimmy Murphy crossed the line to take victory at an average of 94.484 mph, setting a new record. Hartz finished second, Hill third, sealing a 1-2-3 finish for Duesenberg.

It was the first time in history that an American driver, in an American-built car, powered by an American-built engine, won the Indianapolis 500. The Speedway’s dream of a truly homegrown triumph had finally been realized.

Aftermath and Legacy

Jimmy Murphy’s 1922 win marked a watershed moment for American motorsport. The Duesenberg Straight Eight represented the pinnacle of U.S. engineering sophistication, bridging the gap between the elegant Peugeots of the 1910s and the precision-built Miller powerplants that would soon dominate.

Murphy’s drive also elevated the professional image of the American racing driver. Calm, analytical, and fast, he was regarded as the perfect blend of racer and engineer—an archetype that would define the sport’s heroes for decades.

Tragically, Murphy’s career was short-lived. He would die in 1924 during a dirt-track accident, but his legacy endured in every American engine that followed his Duesenberg across the bricks.

The Duesenberg brothers, buoyed by this triumph, would later turn their attention to luxury automobiles—yet their racing innovations became the DNA of American competition.

Reflections

The 1922 Indianapolis 500 was more than a race—it was a declaration. It proved that America could not only match European craftsmanship but surpass it. The smooth rhythm of Murphy’s Duesenberg heralded the birth of the modern American race car: light, balanced, and fast.

From that day forward, Indianapolis was no longer just a test of endurance. It was a showcase of engineering excellence—of innovation born not abroad, but at home in the heart of Indiana.

Sources

Indianapolis Motor Speedway Archives — “Official Records of the 1922 International 500-Mile Sweepstakes” (IMS Heritage Collection)

Motorsport Magazine Archive — “Jimmy Murphy and the First All-American Win” (May 2022 Centennial Feature)

The Indianapolis Star, May 31 – June 1, 1922 — Race and technical coverage

Automobile Quarterly, Vol. 26, No. 2 (1988) — “The Duesenberg Legacy: From Track to Road”

Harry Miller Engineering Papers, Los Angeles Public Library Collection

Smithsonian Institution — Transportation Collections: Duesenberg Straight Eight Design Documentation

1923 Indianapolis 500 — The Age of Speed and Science

Date: May 30, 1923

Circuit: Indianapolis Motor Speedway (2.5 mi oval, brick surface)

Distance: 500 miles (200 laps)

Entries: 24 starters

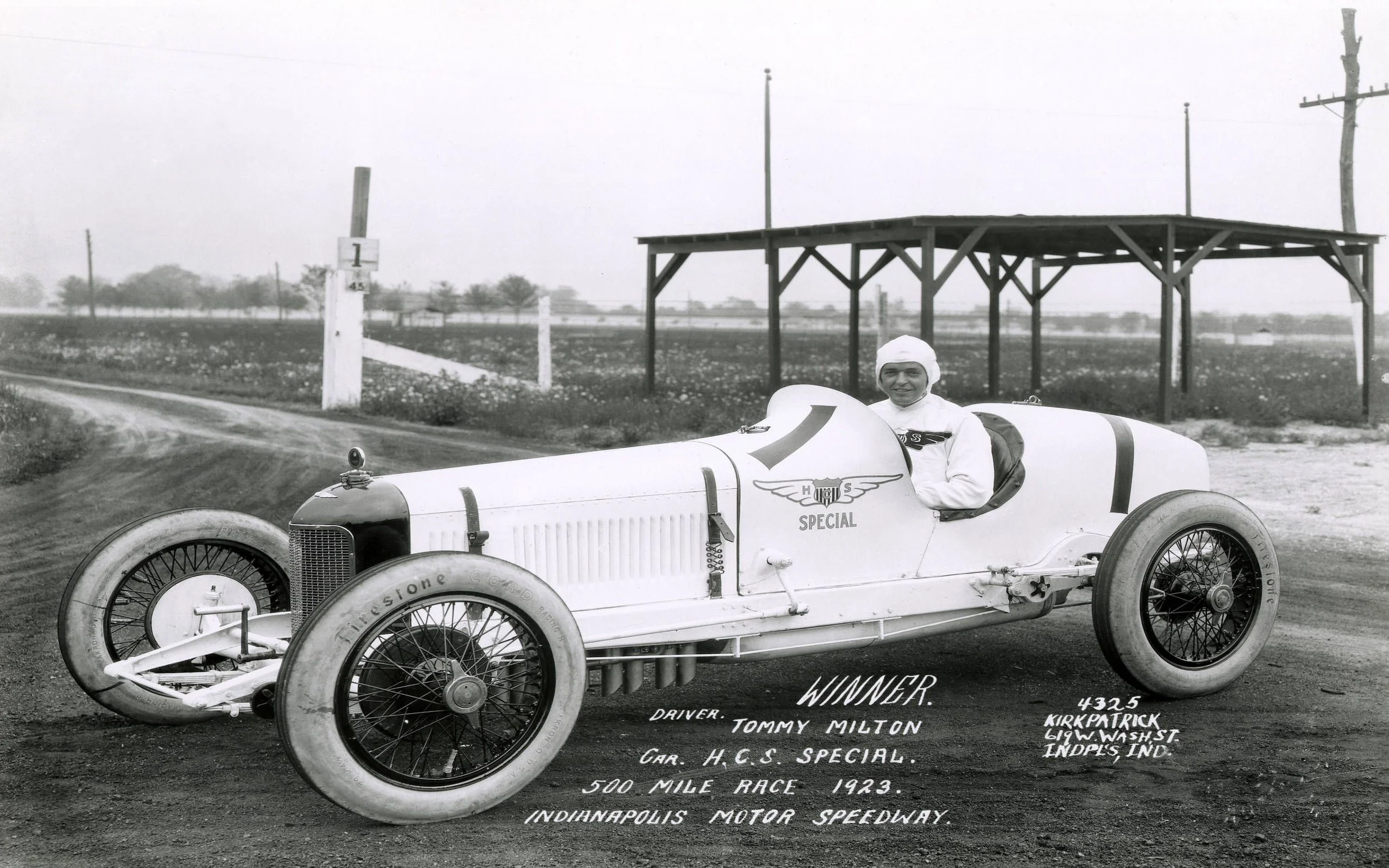

Winner: Tommy Milton — Miller 122

Average Speed: 90.954 mph

Prelude to the Eleventh Running

By 1923, the Indianapolis 500 had fully evolved from a grueling endurance trial into a contest of engineering precision. The pioneering years of improvisation were gone; in their place stood professional teams, factory-backed efforts, and a new generation of engineers who treated speed as a science.

At the center of this revolution was Harry A. Miller, the Los Angeles-based mechanical genius who had absorbed the lessons of Peugeot and Duesenberg and turned them into a uniquely American art form. His new Miller 122—so named for its 122-cubic-inch displacement limit—was the purest expression of that art: light, aerodynamic, and designed to extract maximum efficiency from every revolution.

The man chosen to showcase it was Tommy Milton, the analytical Minnesota driver who had already claimed victory in 1921 with a Frontenac. Intelligent, methodical, and technically adept, Milton understood that Miller’s creation was not a brute-force racer—it was a precision instrument.

The Field and the Machines

The 1923 grid was smaller than usual, but its quality was unmatched. Duesenberg, Frontenac, and Miller were all represented, alongside privateer entries using hybrid designs built around Miller engines. The cars were faster, lower, and more aerodynamic than any field before them.

The Miller 122, with its twin-overhead-cam, four-valve inline-eight engine, produced approximately 155 horsepower—delivered through a finely tuned carburetion system and a lightweight chassis of aluminum and nickel steel. Its engineering sophistication was far ahead of its time.

Milton’s principal challengers included Harry Hartz (Duesenberg Special), Jimmy Murphy (Miller Special, the 1922 champion), and Harlan Fengler (Frontenac).

Race Day

The race began under mild skies and ideal conditions. As the field rolled to the start, the polished aluminum noses of the Millers gleamed under the morning sun—a reflection of America’s new industrial confidence.

From the drop of the flag, Jimmy Murphy surged into the lead, his pace reminiscent of his dominant 1922 performance. But as the laps wore on, his car began to show signs of strain. Milton, running a measured rhythm just behind, took advantage when Murphy’s engine developed valve issues around lap 90.

The Duesenbergs of Hartz and Hearne mounted brief challenges, but Milton’s consistency and Miller’s flawless engineering proved unassailable. The Miller 122’s smaller displacement, designed for efficiency under the new engine formula, allowed Milton to stretch fuel stints and reduce pit time—critical advantages in an age before precise timing systems.

The Final Miles

By the closing stages, Milton was in complete control. His Miller ran cleanly, the engine note crisp even after five hours of sustained high-speed running. Hartz’s Duesenberg mounted a late charge but could not close the gap.

After 5 hours, 29 minutes, 7 seconds, Tommy Milton crossed the finish line with an average speed of 90.954 mph, becoming the first two-time winner of the Indianapolis 500. Hartz finished second, Fengler third, and Jimmy Murphy limped home in fourth with a failing engine.

Aftermath and Legacy

Milton’s 1923 victory marked the true beginning of the Miller Era—a period of technological dominance that would define the Indianapolis 500 for the next two decades. Harry Miller’s engines and chassis would go on to win every 500 from 1923 through 1938, either directly or through descendants built under the Offenhauser name.

The Miller 122 represented a paradigm shift in design philosophy: small displacement, high revs, and mechanical precision over raw size or power. It was, in essence, the first modern Indy car.

For Tommy Milton, the win solidified his reputation as America’s first great “thinking driver.” He retired from full-time competition soon after, later serving as the Speedway’s Chief Steward. His combination of technical understanding and restraint became the model for generations to follow.

Reflections

The 1923 Indianapolis 500 was a declaration of modernity. It was the race where American innovation, engineering discipline, and driver intellect converged. The Miller 122 was not just fast—it was efficient, aerodynamic, and purpose-built, heralding the scientific age of motorsport.

Milton’s mastery of both machine and mind transformed victory from an act of luck into a process of calculation. The rough-edged heroism of the early years gave way to the cool precision of the modern era—and the Speedway, once a proving ground for invention, became a temple of engineering.

Sources

Indianapolis Motor Speedway Archives — “Official Records of the 1923 International 500-Mile Sweepstakes” (IMS Heritage Collection)

Motorsport Magazine Archive — “Tommy Milton and the Rise of the Miller Era” (May 2023 Centennial Feature)

The Indianapolis Star, May 31 – June 1, 1923 — Race-day and technical reports

Automobile Quarterly, Vol. 28, No. 2 (1990) — “Miller’s Revolution: The Engine That Changed Indy”

Harry A. Miller Engineering Papers, Los Angeles Public Library Collection

Smithsonian Institution — Transportation Collections: Miller 122 Engine Design Drawings and Specifications

1924 Indianapolis 500 — Duesenberg’s Last Glory

Date: May 30, 1924

Circuit: Indianapolis Motor Speedway (2.5 mi oval, brick surface)

Distance: 500 miles (200 laps)

Entries: 22 starters

Winner: Joe Boyer / L. L. Corum — Duesenberg Special

Average Speed: 98.234 mph

Prelude to the Twelfth Running

By 1924, the Indianapolis 500 had become the world’s most important race. The Speedway’s field, though smaller than in the early years, was now the most refined, technologically advanced grid yet assembled. The rivalry between Harry Miller’s lightweight, jewel-like creations and the Duesenberg brothers’ brawnier, supercharged eight-cylinders defined the era.

The previous year had ushered in the Miller Revolution, but the Duesenberg brothers—Fred and August—were not ready to yield. Their new supercharged straight-eight aimed to reclaim the crown for mechanical durability and sheer power. Where the Miller 122 emphasized finesse, the Duesenberg relied on endurance and torque.

This would be Duesenberg’s final stand as a factory team at the Speedway, and it unfolded in a manner so dramatic it has since entered Indy lore.

The Field and the Machines

The 1924 starting lineup featured 22 cars, with a technical duel between Miller’s 122s and Duesenberg’s 122 supercharged machines. The Duesenbergs, tuned by Fred Duesenberg himself, produced nearly 170 horsepower—the most powerful cars yet to start the 500.

Joe Boyer, a Detroit driver known for his speed but hampered by misfortune, started one of the Duesenberg team cars. His teammate L. L. “Louis” Corum, piloting the second factory Duesenberg, was equally quick. Other challengers included Jimmy Murphy (Miller Special), Harry Hartz, and Eddie Hearne—each in variations of Miller-based designs.

The temperature soared past 90°F on race day, testing both driver stamina and mechanical resilience.

Race Day

The 1924 race began with familiar intensity. Jimmy Murphy, the 1922 champion, took an early lead in his Miller, setting a torrid pace. But by lap 50, the combination of blistering heat and relentless speed began claiming victims. Murphy’s car suffered tire failures, forcing lengthy pit stops.

Meanwhile, Joe Boyer led early in his Duesenberg before mechanical issues slowed him. At the 111-lap mark, Boyer retired to the pits, dejected. But Fred Duesenberg had a plan: he ordered Boyer to relieve teammate L. L. Corum, whose own Duesenberg was running steadily in the top five.

Boyer took over the Corum car at lap 111—and from that moment, the race transformed. He drove with renewed fury, closing a massive gap to the leaders while managing the car’s fragile supercharger with mechanical sympathy.

As the afternoon wore on, Murphy’s Miller succumbed to valve trouble, and Hartz’s Duesenberg lost oil pressure. Boyer—now driving Corum’s No. 15 car—surged into the lead.

The Final Miles

With 20 laps remaining, the Corum/Boyer Duesenberg roared past the grandstands with a two-lap advantage. Despite the scorching heat, Boyer maintained a blistering average of nearly 100 mph—an astonishing figure for the brick surface and fragile tires of the era.

When the checkered flag fell after 5 hours, 5 minutes, and 17 seconds, Joe Boyer took the victory for himself, for Corum, and for Duesenberg. It was the first shared win in Indianapolis 500 history—and remains one of the race’s most dramatic stories.

Corum was officially listed as co-winner, having driven the car’s first 111 laps, but it was Boyer’s relentless comeback that sealed the triumph. The winning average speed of 98.234 mph shattered previous records, and Duesenberg became the first manufacturer to win the Indianapolis 500 twice.

Aftermath and Legacy

The 1924 Indianapolis 500 represented both a triumph and a farewell. For Duesenberg, it was their final factory victory at the Speedway before turning full attention to luxury road cars. Their engineering legacy, however, would ripple through generations: their straight-eight designs directly influenced the later Miller 91 and, ultimately, the Offenhauser lineage that would dominate the 500 for half a century.

For Joe Boyer, it was the crowning achievement of his career. Tragically, like so many of his era, he would lose his life just months later in a racing accident at Altoona Speedway. His courage and comeback performance, however, remain immortal in Indianapolis history.

The shared victory rule introduced by Boyer and Corum’s drive would later lead to formal regulations for relief drivers—a testament to the physical and mechanical demands of early Indy competition.

Reflections

The 1924 Indianapolis 500 was racing at its most human—a blend of tragedy, teamwork, and technical evolution. The shared Duesenberg victory symbolized both the camaraderie and the fragility of motorsport’s early heroes.

It was also the closing chapter of the great early-engineering rivalry. Miller’s elegance and Duesenberg’s durability had defined the early 1920s, but this race—won through teamwork and tenacity—marked the final triumph of the old guard before the era of the supercharged Miller and the precision-built Offenhauser began.

The bricks of the Speedway had never seen such speed, and perhaps never again would see such resilience.

Sources

Indianapolis Motor Speedway Archives — “Official Records of the 1924 International 500-Mile Sweepstakes” (IMS Heritage Collection)

Motorsport Magazine Archive — “The Shared Triumph: Boyer, Corum, and Duesenberg 1924” (May 2024 Centennial Feature)

The Indianapolis Star, May 31 – June 1, 1924 — Race coverage and post-race analysis

Automobile Quarterly, Vol. 30, No. 1 (1992) — “Duesenberg’s Last Victory”

Fred Duesenberg Papers, Auburn Cord Duesenberg Museum Archives

Smithsonian Institution — Transportation Collections: Duesenberg Supercharged Engine Technical Files

1925 Indianapolis 500 — The First to 100

Date: May 30, 1925

Circuit: Indianapolis Motor Speedway (2.5 mi oval, brick surface)

Distance: 500 miles (200 laps)

Entries: 25 starters

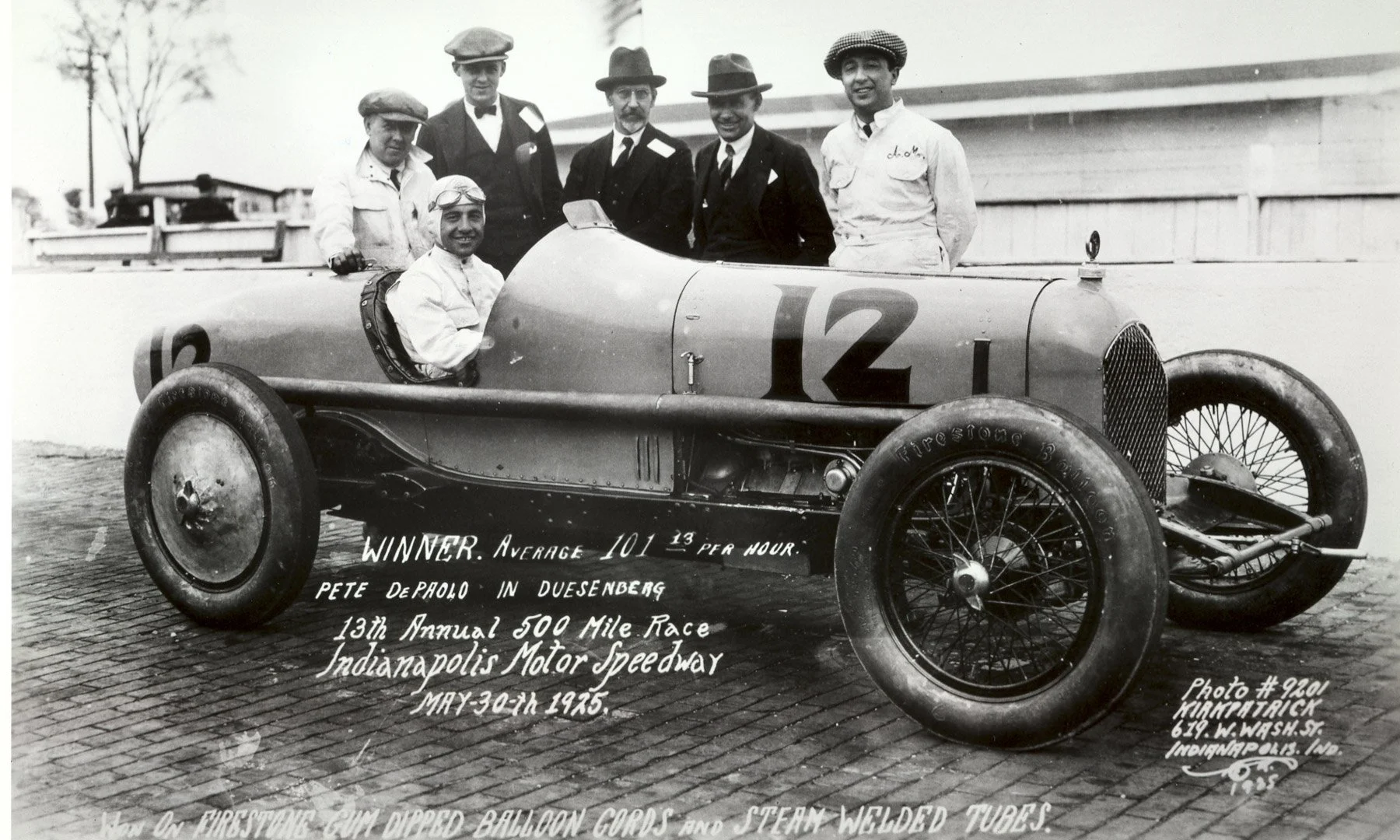

Winner: Peter DePaolo — Duesenberg Special

Average Speed: 101.127 mph

Prelude to the Thirteenth Running

By 1925, the Indianapolis 500 had entered the modern age of racing. The crude, experimental years of hand-pumped oil and leather helmets had given way to precise pitwork, aerodynamic streamlining, and scientific engineering. The cars were faster, lighter, and more dangerous than ever before.

The previous year’s race had ended in triumph for Duesenberg, but Harry Miller’s supercharged engines were now dominating the grids across America. Miller’s designs were efficient and elegant—machined like jewelry, tuned like instruments. Yet the Duesenberg brothers were not ready to be eclipsed.

They entered the 1925 race with a new generation of supercharged straight-eights, featuring improved lubrication and four-valve cylinder heads. The car was driven by Peter DePaolo, the nephew of the late Ralph DePalma, who had endured so much heartbreak at Indianapolis. The 1925 race would become DePaolo’s redemption of that family legacy—and a turning point for the sport.

The Field and the Machines

The 1925 field represented a technical arms race between Miller and Duesenberg. Miller’s compact 122-cubic-inch straight-eights had been the standard since 1923, but the Duesenberg team’s new supercharged variant pushed the envelope even further—producing around 200 horsepower, an astonishing figure for the time.

DePaolo’s No. 12 Duesenberg Special, co-driven by Norm Batten, was prepared by the Duesenberg factory with meticulous attention to cooling and gearing. The team’s rivals included Harry Hartz in a Miller, Dave Lewis in a front-drive Miller, and Leon Duray, piloting a privately built Miller Special.

Though the field numbered just 25 cars, its quality was unmatched. Every entry represented the cutting edge of American engineering.

Race Day

Memorial Day dawned hot and clear. More than 135,000 spectators crowded the Speedway—the largest post-war attendance yet recorded. The atmosphere was electric with anticipation: many believed this would be the year someone finally averaged 100 mph over 500 miles.

At the start, Harry Hartz and Dave Lewis surged to the front, their Millers carving smooth, consistent laps in the high 90s. DePaolo ran third early on, maintaining a calm, even pace. The heat took a brutal toll: by mid-race, several cars retired with tire failures and overheating engines.

On lap 106, disaster nearly struck. DePaolo’s hands were badly blistered from the heat radiating through the thin steering wheel rim. At the 300-mile mark, he pitted and was relieved by teammate Norm Batten, who drove 21 laps while DePaolo’s hands were treated with alcohol and bandages.

When DePaolo climbed back into the car, he was bloodied but unshaken. With both hands wrapped and his face streaked with oil, he began to charge. The Duesenberg’s supercharged engine howled down the straights, its whine echoing across the stands.

The Final Miles

In the final 50 laps, DePaolo overtook Hartz to seize the lead. Despite his injuries, he maintained a relentless pace—lapping consistently at over 103 mph. The pit crew signaled that he was on track to break the 100 mph average barrier, but the crowd hardly needed confirmation: they could see the speed.

After 4 hours, 56 minutes, and 29 seconds, Peter DePaolo crossed the finish line to make history. His average speed of 101.127 mph shattered records, making him the first driver to average over 100 mph in the Indianapolis 500.

It was a symbolic victory for both driver and manufacturer: the culmination of two decades of mechanical progress since Ray Harroun’s 74 mph win in 1911.

Aftermath and Legacy

Peter DePaolo’s 1925 win remains one of the defining moments in Indianapolis history. His battered hands and steely determination captured the imagination of the public, while his technical mastery earned him respect among engineers.

The 100 mph barrier became a new benchmark—the line between the early years of endurance and the modern pursuit of sustained speed. Duesenberg’s victory was its last at Indianapolis, closing an era of factory racing that had begun in 1912.

For DePaolo, the triumph launched a storied career that would span racing, writing, and aviation. His memoir, Wall Smacker, published years later, immortalized the dangers and exhilaration of the 1920s speed era.

For engineers, the 1925 race signaled the beginning of relentless technical pursuit: smaller displacements, forced induction, lighter chassis, and eventually, front-wheel drive. The Indianapolis 500 had become a crucible of progress.

Reflections

The 1925 Indianapolis 500 was not simply a race—it was a threshold. The century speed barrier transformed the event from a test of endurance into a laboratory of speed.

Peter DePaolo’s victory embodied the spirit of the age: brave, ingenious, and unyielding. The Duesenberg Special’s scream across the bricks heralded a new world where machinery and mathematics combined to rewrite the limits of possibility.

From this moment onward, Indianapolis would belong not just to the brave—but to the brilliant.

Sources

Indianapolis Motor Speedway Archives — “Official Records of the 1925 International 500-Mile Sweepstakes” (IMS Heritage Collection)

Motorsport Magazine Archive — “DePaolo Breaks the Barrier: The 1925 Indianapolis 500” (May 2025 Centennial Feature)

The Indianapolis Star, May 31 – June 1, 1925 — Race-day and technical coverage

Automobile Quarterly, Vol. 31, No. 2 (1993) — “The First to 100: DePaolo and Duesenberg’s Final Triumph”

Peter DePaolo Papers, National Automotive History Collection, Detroit Public Library

Smithsonian Institution — Transportation Collections: Duesenberg Supercharged Engine Blueprints

1926 Indianapolis 500 — The Boy Wonder and the Miller Revolution

Date: May 31, 1926

Circuit: Indianapolis Motor Speedway (2.5 mi oval, brick surface)

Distance: 400 miles (160 laps; race shortened by rain)

Entries: 25 starters

Winner: Frank Lockhart — Miller 91 Special

Average Speed: 95.904 mph

Prelude to the Fourteenth Running

By 1926, the Indianapolis 500 had entered an age of pure science and speed. The clattering, endurance-oriented machines of the teens had evolved into elegant, streamlined masterpieces designed for precision. The name on everyone’s lips was Miller—Harry A. Miller, the mechanical artist whose engines had become synonymous with success.

The new Miller 91, named for its 91.5 cubic-inch displacement (1.5 liters), represented the apex of American engineering in the 1920s. Lightweight, supercharged, and meticulously machined from aluminum, it produced roughly 170 horsepower, spinning at over 7,000 rpm—astonishing figures for the time.

And in 1926, the car’s brilliance would meet its perfect pilot: Frank Lockhart, a 23-year-old rookie whose mechanical intuition and fearless precision would make him an instant legend.

The Field and the Machines

The 1926 grid was the fastest yet seen. Nearly every major entry used some form of Miller powerplant, whether factory-built or licensed derivatives. The leading challengers included:

Peter DePaolo, the defending champion, in a supercharged Duesenberg Special.

Harry Hartz, running a Miller Special.

Frank Lockhart, making his debut in a factory-backed Miller 91.

Dave Lewis and Eddie Hearne, both in Miller-powered cars.

Lockhart, driving the No. 15 Miller Special, entered through the Stutz factory team—a symbolic partnership, as Stutz had once been among Miller’s rivals. The car featured a streamlined, narrow body and side-mounted supercharger, allowing it to cut through the air like nothing before it.

Race Day

Rain threatened from dawn. Clouds hung heavy over the Speedway as the 25-car field lined up before 135,000 spectators. When the flag dropped at 10 a.m., the Miller cars surged forward, their shrill superchargers cutting through the humid air.

Peter DePaolo, still nursing injuries from a crash earlier in the month, led the opening laps, but Lockhart’s pace was relentless. Within the first 50 miles, the rookie had surged to the front, setting lap speeds in the 110 mph range—a blistering pace for the era and the weather.

DePaolo’s Duesenberg, though powerful, struggled for grip on the slick bricks, while the Millers—lighter and more responsive—thrived. Lockhart, small in stature but immensely skilled, handled his car with uncanny smoothness, adjusting throttle pressure through the corners to keep the boost steady.

As rain began to fall intermittently after the halfway mark, pit strategy became chaotic. Some teams changed to treaded tires; others gambled on staying out. Lockhart, in a bold decision, remained on slicks, maintaining his rhythm as others faltered.

The Final Miles

By lap 150, Lockhart led comfortably over Dave Lewis and Harry Hartz. Rain intensified, reducing visibility and transforming the bricks into a slick mosaic of danger. Drivers fought simply to keep their cars in line.

On lap 160—400 miles completed—the officials waved the red flag. The track was drenched, and lightning flickered over the grandstands. Lockhart coasted across the line as the youngest winner in Indianapolis 500 history, aged just 23 years and 157 days.

He had led 95 of the 160 laps, dominating the race from the front. His average speed of 95.904 mph under deteriorating conditions was extraordinary—and his mechanical understanding of the Miller 91 had been flawless.

Aftermath and Legacy

Frank Lockhart’s 1926 triumph instantly elevated him to legend. His calm, cerebral driving style and engineering acumen made him a prototype for the modern driver-engineer. In his rookie appearance, he had mastered the most sophisticated machine of its time and outclassed veterans twice his age.

For Harry Miller, the win solidified the supremacy of his designs. The Miller 91, with its small-displacement supercharged engine, represented a radical break from the past—it proved that lightness, revs, and precision could defeat brute force. The car’s influence would echo for decades, forming the mechanical DNA of the later Offenhauser engines that dominated Indy into the 1960s.

Lockhart’s career would be brief but brilliant. He would go on to break land speed records and push the limits of mechanical knowledge before perishing at Daytona in 1928. Yet his name, like Miller’s, became synonymous with the pursuit of perfection.

Reflections

The 1926 Indianapolis 500 was a race of contrasts—youth and experience, rain and speed, innovation and fragility. It was the moment when the spirit of the early pioneers gave way to the engineer’s era.

Frank Lockhart’s mastery of the Miller 91 was not just a victory—it was a revelation. The car and driver together embodied the ideals of efficiency, intelligence, and control that would define the next century of motorsport.

In the rain-soaked silence after the finish, as crews pushed the gleaming Millers back to the garages, the Speedway stood witness to something new: the fusion of art and science at 100 miles per hour.

Sources

Indianapolis Motor Speedway Archives — “Official Records of the 1926 International 500-Mile Sweepstakes” (IMS Heritage Collection)

Motorsport Magazine Archive — “Frank Lockhart: The Boy Wonder of Indianapolis” (May 2026 Centennial Feature)

The Indianapolis Star, May 31 – June 1, 1926 — Race coverage and technical reports

Automobile Quarterly, Vol. 32, No. 3 (1994) — “The Miller 91 and the Birth of Modern Speed”

Harry A. Miller Engineering Papers, Los Angeles Public Library

Smithsonian Institution — Transportation Collections: Miller 91 Technical Drawings and Supercharger Specifications

1927 Indianapolis 500 — The Rise and Fall of the Boy Wonder

Date: May 30, 1927

Circuit: Indianapolis Motor Speedway (2.5 mi oval, brick surface)

Distance: 500 miles (200 laps)

Entries: 28 starters

Winner: George Souders — Duesenberg Special

Average Speed: 97.545 mph

Prelude to the Fifteenth Running

The 1927 Indianapolis 500 was held at the height of the Roaring Twenties, and it felt every bit the part. The cars gleamed in polished aluminum, the grandstands were packed to capacity, and the Speedway had become America’s annual cathedral of speed.

The dominant name was still Miller. Harry Miller’s genius had rewritten the language of racecar engineering—his engines, chassis, and superchargers were the envy of the world. But as the Miller 91 grew smaller, lighter, and more powerful, reliability became an ever more delicate balance.

Returning as reigning champion was Frank Lockhart, the wunderkind who had stunned the racing world the year before with his rain-shortened rookie victory. Now, at 24 years old, he was the undisputed favorite—a driver-engineer at the height of his powers, piloting the latest evolution of the supercharged Miller 91.

The Field and the Machines

The 1927 grid featured a technical arms race between Miller’s relentless innovation and Duesenberg’s evolving engineering philosophy. Nearly 23 of the 28 starters carried Miller engines or derivatives.

Lockhart’s new No. 15 Miller 91 Front-Drive Special was among the most advanced machines yet built. Featuring front-wheel drive (a revolutionary concept), the car promised better traction and stability through corners—especially on the worn, uneven brick surface of the Speedway.

His challengers included:

Peter DePaolo, 1925 champion, in a supercharged Duesenberg.

Harry Hartz, perennial contender, in a Miller 91.

George Souders, a relative unknown in a privately entered Duesenberg.

Though the field brimmed with technical brilliance, few doubted Lockhart’s supremacy.

Race Day

Race morning broke humid and breezy, with perfect visibility and a festive mood among the 140,000 spectators. When the green flag dropped, Lockhart leapt into the lead immediately, his front-drive Miller gliding effortlessly through the turns. His smooth, scientific driving style made the car appear untouchable.

For the first 100 miles, Lockhart was in total command—lapping consistently above 110 mph, pulling away from the field with ease. Behind him, Souders and Hartz traded second and third, both keeping a cautious distance.

Then, on lap 120, the sound of the Miller’s supercharger began to falter. Lockhart’s car slowed visibly, the engine coughing smoke. A connecting rod failure forced him to coast into the pits—his race over. The grandstands fell silent. The young prodigy, who had seemed destined to dominate a generation, was done for the day.

As Lockhart’s mechanics pushed his stricken Miller behind the wall, the race continued to unfold in unpredictable fashion. The favored Millers began to fall away one by one—superchargers bursting, pistons seizing, or magnetos failing in the heat.

The Final Miles

Into this chaos stepped George Souders, the unheralded 26-year-old from Lafayette, Indiana. Driving a year-old Duesenberg Special, Souders had run quietly all afternoon, maintaining a steady rhythm while faster cars self-destructed. His simple, naturally aspirated engine—less exotic but far more durable—proved the key to survival.

By lap 150, Souders had inherited the lead, and by lap 180, he was the only major contender still running without issue. He drove the final 20 laps with steady precision, never pushing beyond what the car would bear.

After 5 hours, 7 minutes, and 7 seconds, George Souders crossed the finish line to claim victory—an astonishing upset against the Miller juggernaut. His average speed of 97.545 mph was a testament to consistency, not raw power.

Souders became the first driver to win the Indianapolis 500 in his rookie appearance since Lockhart, just one year earlier.

Aftermath and Legacy

The 1927 Indianapolis 500 was a race of paradoxes. It was at once Miller’s technical zenith and his practical undoing. The Miller 91s were unrivaled in speed and engineering beauty—but their fragility cost them dearly.

For George Souders, the win was the crowning moment of a brief but brilliant career. His victory was hailed as a triumph of prudence over pressure, of reliability over risk. He returned in 1928 to finish second, confirming that his success had been no fluke.

For Frank Lockhart, the race was a cruel prelude. Just months later, he would pursue land speed records at Daytona Beach, where he was tragically killed in a 200 mph crash in his twin-supercharged Miller. His legacy—brilliance, precision, and courage—remains one of American racing’s most enduring myths.

The 1927 race also marked the beginning of the end for front-wheel drive at Indianapolis. Though innovative, the complexity and maintenance demands outweighed its advantages until its revival decades later.

Reflections

The 1927 Indianapolis 500 was a study in contrast—the fall of a prodigy, the rise of an underdog, and the fragile balance between speed and survival. It was the moment when the sport’s technical brilliance collided with its human cost.

Souders’ steady triumph closed an era of escalating fragility, while Lockhart’s heartbreak foreshadowed the perils of racing’s relentless pursuit of speed. The Miller 91 would remain an engineering masterpiece, but 1927 proved that even perfection on paper could not conquer the element of chance.

Under the golden sun of that Indiana afternoon, victory once again belonged not to the fastest—but to the one who endured.

Sources

Indianapolis Motor Speedway Archives — “Official Records of the 1927 International 500-Mile Sweepstakes” (IMS Heritage Collection)

Motorsport Magazine Archive — “Souders and the Shadow of Lockhart” (May 2027 Centennial Feature)

The Indianapolis Star, May 31 – June 1, 1927 — Race-day and post-race coverage

Automobile Quarterly, Vol. 33, No. 1 (1995) — “Miller’s Masterpieces and the Limits of Perfection”

Harry A. Miller Engineering Papers, Los Angeles Public Library

Smithsonian Institution — Transportation Collections: Miller 91 Front-Drive Blueprints and Duesenberg Technical Notes

1927 Indianapolis 500 — The Rise and Fall of the Boy Wonder

Date: May 30, 1927

Circuit: Indianapolis Motor Speedway (2.5 mi oval, brick surface)

Distance: 500 miles (200 laps)

Entries: 28 starters

Winner: George Souders — Duesenberg Special

Average Speed: 97.545 mph

Prelude to the Fifteenth Running

The 1927 Indianapolis 500 was held at the height of the Roaring Twenties, and it felt every bit the part. The cars gleamed in polished aluminum, the grandstands were packed to capacity, and the Speedway had become America’s annual cathedral of speed.

The dominant name was still Miller. Harry Miller’s genius had rewritten the language of racecar engineering—his engines, chassis, and superchargers were the envy of the world. But as the Miller 91 grew smaller, lighter, and more powerful, reliability became an ever more delicate balance.

Returning as reigning champion was Frank Lockhart, the wunderkind who had stunned the racing world the year before with his rain-shortened rookie victory. Now, at 24 years old, he was the undisputed favorite—a driver-engineer at the height of his powers, piloting the latest evolution of the supercharged Miller 91.

The Field and the Machines

The 1927 grid featured a technical arms race between Miller’s relentless innovation and Duesenberg’s evolving engineering philosophy. Nearly 23 of the 28 starters carried Miller engines or derivatives.

Lockhart’s new No. 15 Miller 91 Front-Drive Special was among the most advanced machines yet built. Featuring front-wheel drive (a revolutionary concept), the car promised better traction and stability through corners—especially on the worn, uneven brick surface of the Speedway.

His challengers included:

Peter DePaolo, 1925 champion, in a supercharged Duesenberg.

Harry Hartz, perennial contender, in a Miller 91.

George Souders, a relative unknown in a privately entered Duesenberg.

Though the field brimmed with technical brilliance, few doubted Lockhart’s supremacy.

Race Day

Race morning broke humid and breezy, with perfect visibility and a festive mood among the 140,000 spectators. When the green flag dropped, Lockhart leapt into the lead immediately, his front-drive Miller gliding effortlessly through the turns. His smooth, scientific driving style made the car appear untouchable.

For the first 100 miles, Lockhart was in total command—lapping consistently above 110 mph, pulling away from the field with ease. Behind him, Souders and Hartz traded second and third, both keeping a cautious distance.

Then, on lap 120, the sound of the Miller’s supercharger began to falter. Lockhart’s car slowed visibly, the engine coughing smoke. A connecting rod failure forced him to coast into the pits—his race over. The grandstands fell silent. The young prodigy, who had seemed destined to dominate a generation, was done for the day.

As Lockhart’s mechanics pushed his stricken Miller behind the wall, the race continued to unfold in unpredictable fashion. The favored Millers began to fall away one by one—superchargers bursting, pistons seizing, or magnetos failing in the heat.

The Final Miles

Into this chaos stepped George Souders, the unheralded 26-year-old from Lafayette, Indiana. Driving a year-old Duesenberg Special, Souders had run quietly all afternoon, maintaining a steady rhythm while faster cars self-destructed. His simple, naturally aspirated engine—less exotic but far more durable—proved the key to survival.

By lap 150, Souders had inherited the lead, and by lap 180, he was the only major contender still running without issue. He drove the final 20 laps with steady precision, never pushing beyond what the car would bear.

After 5 hours, 7 minutes, and 7 seconds, George Souders crossed the finish line to claim victory—an astonishing upset against the Miller juggernaut. His average speed of 97.545 mph was a testament to consistency, not raw power.

Souders became the first driver to win the Indianapolis 500 in his rookie appearance since Lockhart, just one year earlier.

Aftermath and Legacy

The 1927 Indianapolis 500 was a race of paradoxes. It was at once Miller’s technical zenith and his practical undoing. The Miller 91s were unrivaled in speed and engineering beauty—but their fragility cost them dearly.

For George Souders, the win was the crowning moment of a brief but brilliant career. His victory was hailed as a triumph of prudence over pressure, of reliability over risk. He returned in 1928 to finish second, confirming that his success had been no fluke.

For Frank Lockhart, the race was a cruel prelude. Just months later, he would pursue land speed records at Daytona Beach, where he was tragically killed in a 200 mph crash in his twin-supercharged Miller. His legacy—brilliance, precision, and courage—remains one of American racing’s most enduring myths.

The 1927 race also marked the beginning of the end for front-wheel drive at Indianapolis. Though innovative, the complexity and maintenance demands outweighed its advantages until its revival decades later.

Reflections

The 1927 Indianapolis 500 was a study in contrast—the fall of a prodigy, the rise of an underdog, and the fragile balance between speed and survival. It was the moment when the sport’s technical brilliance collided with its human cost.

Souders’ steady triumph closed an era of escalating fragility, while Lockhart’s heartbreak foreshadowed the perils of racing’s relentless pursuit of speed. The Miller 91 would remain an engineering masterpiece, but 1927 proved that even perfection on paper could not conquer the element of chance.

Under the golden sun of that Indiana afternoon, victory once again belonged not to the fastest—but to the one who endured.

Sources

Indianapolis Motor Speedway Archives — “Official Records of the 1927 International 500-Mile Sweepstakes” (IMS Heritage Collection)

Motorsport Magazine Archive — “Souders and the Shadow of Lockhart” (May 2027 Centennial Feature)

The Indianapolis Star, May 31 – June 1, 1927 — Race-day and post-race coverage

Automobile Quarterly, Vol. 33, No. 1 (1995) — “Miller’s Masterpieces and the Limits of Perfection”

Harry A. Miller Engineering Papers, Los Angeles Public Library

Smithsonian Institution — Transportation Collections: Miller 91 Front-Drive Blueprints and Duesenberg Technical Notes

1928 Indianapolis 500 — The Birth of a Legend

Date: May 30, 1928

Circuit: Indianapolis Motor Speedway (2.5 mi oval, brick surface)

Distance: 500 miles (200 laps)

Entries: 33 starters

Winner: Louis Meyer — Miller Special

Average Speed: 99.482 mph

Prelude to the Sixteenth Running

The 1928 Indianapolis 500 stood at the crossroads between two ages. The romantic, barnstorming era of the 1910s and early ’20s had faded, and in its place rose a new culture of disciplined professionalism. Racing teams now resembled engineering laboratories—every nut and rivet tested, every lap meticulously planned.

The tragedy of Frank Lockhart’s fatal record attempt at Daytona earlier that spring still hung heavily over the paddock. His death at just 25 symbolized both the brilliance and the peril of speed’s new frontier. Yet his influence—technical precision, aerodynamic thought, and mechanical purity—permeated every car on the 1928 grid.

The race would be defined by a different kind of hero: a humble, methodical young Californian named Louis Meyer, a quiet mechanic-turned-driver making his first Indianapolis start. His victory would begin one of the most remarkable careers in the Speedway’s long history.

The Field and the Machines

By 1928, the Miller 91 had become the standard-bearer of Indianapolis engineering. Every serious contender fielded either a factory Miller or a car powered by a Miller engine. The front-drive experiments of 1927 had largely been abandoned, replaced by conventional rear-drive configurations refined for balance and reliability.

The key entrants included:

Harry Hartz, the experienced favorite, driving his Miller Special.

Ray Keech, in a factory-backed Miller.

Louis Meyer, in a Tydol Miller Special, entered by the Alden Sampson team.

Cliff Woodbury, in another front-drive Miller.

The Miller engines were now producing nearly 200 horsepower from just 91 cubic inches, spinning freely above 7,000 rpm. But while they were mechanical marvels, they were also temperamental—fragile under heat and vibration.

Race Day

Race morning brought heavy clouds and damp air, but no rain. The field of 33 cars rolled onto the bricks before more than 140,000 spectators. When the green flag fell, Harry Hartz immediately took control, setting a blistering early pace in his red Miller Special.

For the first 150 miles, Hartz and Ray Keech traded the lead repeatedly, running near 105 mph average. Behind them, Louis Meyer drove quietly, staying out of trouble and maintaining his own careful rhythm. He had been a mechanic before he was a driver, and his understanding of the car’s limits would prove decisive.

By mid-race, the attrition began. Engines failed, superchargers burst, and clutches disintegrated under the relentless pace. Hartz’s Miller began misfiring near the 400-mile mark, and Keech’s car developed oil pressure problems.

Meyer, steady as clockwork, inherited the lead. He drove without error—smooth, consistent, and almost unnervingly calm for a first-timer. As others pressed too hard, he let mechanical attrition come to him.

The Final Miles

In the closing stages, Lou Meyer continued to lap at near-record pace, never once over-revving his engine or missing a braking point. His pit crew—led by the legendary mechanic August Offenhauser, then Miller’s chief engineer—signaled him to ease back slightly as the race drew to its end.

After 5 hours, 1 minute, 48 seconds, Meyer crossed the finish line at an average speed of 99.482 mph, just shy of the elusive 100 mph barrier but comfortably ahead of second-place Dave Evans.

At 23 years old, Louis Meyer became the first driver to win the Indianapolis 500 on debut since George Souders the year before. His quiet intelligence and mechanical empathy set him apart from the daredevils of old—he was the first of a new breed: the thinking driver.

Aftermath and Legacy

Meyer’s victory marked both an end and a beginning. It was the final Indianapolis 500 won under the original “Miller era”—the last before the Great Depression reshaped the sport. It was also the first victory for August Offenhauser, who had built and tuned Meyer’s winning engine. Within a decade, Offenhauser’s own engines would evolve from Miller’s designs to dominate Indianapolis for more than 40 years.

For Meyer, the win launched an extraordinary legacy. He would go on to become the first three-time Indianapolis 500 winner (1928, 1933, 1936) and the originator of one of Indy’s greatest traditions: drinking a bottle of milk in Victory Lane.

The 1928 race also underscored the Speedway’s transformation. No longer was the event about mechanical survival—it was about efficiency, refinement, and preparation. The age of reckless heroism had given way to the era of mastery.

Reflections

The 1928 Indianapolis 500 was a quiet revolution. It lacked the high drama of earlier years, but in its place came something more enduring: professionalism. Louis Meyer’s calm, methodical drive represented a new ideal for the sport—an understanding that speed was not a matter of force, but of harmony.

His partnership with Offenhauser marked the passing of a torch. Harry Miller’s era of artistic engineering had reached perfection, and now his protégé would turn that artistry into an empire.

On that overcast May afternoon, as Meyer took the checkered flag, Indianapolis entered a new age—one where the future of American racing would hum to the tune of a Miller engine, and later, an Offenhauser’s song.

Sources

Indianapolis Motor Speedway Archives — “Official Records of the 1928 International 500-Mile Sweepstakes” (IMS Heritage Collection)

Motorsport Magazine Archive — “Louis Meyer and the Making of the Modern Indy 500” (May 2028 Centennial Feature)

The Indianapolis Star, May 31 – June 1, 1928 — Race coverage and pit reports

Automobile Quarterly, Vol. 34, No. 2 (1996) — “Miller to Offenhauser: The Transfer of Genius”

Harry A. Miller / August Offenhauser Papers, Los Angeles Public Library & National Automotive History Collection

Smithsonian Institution — Transportation Collections: Miller 91 and Offenhauser prototype documentation

1929 Indianapolis 500 — The Last Roar of the Twenties

Date: May 30, 1929

Circuit: Indianapolis Motor Speedway (2.5 mi oval, brick surface)

Distance: 500 miles (200 laps)

Entries: 33 starters

Winner: Ray Keech — Miller Special

Average Speed: 97.585 mph

Prelude to the Seventeenth Running

The 1929 Indianapolis 500 arrived at the height of American optimism—and, unknowingly, on the brink of its collapse. The nation thrummed with confidence: automobiles filled the roads, radios filled the air, and the Speedway, now 18 years old, was the proudest arena of American technology.

The engineering war between Harry Miller’s lightweight precision and Duesenberg’s muscular power had reached its zenith. Nearly every car in the field carried Miller DNA in some form, from full factory machines to private entries built around Miller engines or chassis.

Yet, as the age of speed grew faster, it also grew more fragile. The 1929 race would feature innovation and tragedy in equal measure—marking both the triumph of Ray Keech, one of the era’s most daring drivers, and the final pre-Depression chapter of unrestrained excess at the Brickyard.

The Field and the Machines

By 1929, the technical language of Indianapolis had become synonymous with “Miller.” Of the 33 starters, 27 were powered by Miller engines—either the proven 91 cubic-inch supercharged eight or variations built under license.

The headline entries included:

Ray Keech, in the No. 2 Miller Special, built by Phil “P.C.” Klein and tuned by Herman Rigling.

Cliff Woodbury, driving a front-drive Miller, representing the revived interest in front-wheel-drive designs.

Louis Meyer, the reigning champion, in a rear-drive Miller Special.

Wilbur Shaw, a promising young driver in a Boyle Valve Miller.

George Souders, 1927 winner, in a Duesenberg.

Keech’s Miller 91 featured a supercharged straight-eight engine producing around 200 horsepower, capable of speeds nearing 130 mph on the straights—a mechanical marvel whose limits were stretched perilously thin.

Race Day

The 1929 race dawned hot, clear, and festive—America’s final carefree Indianapolis before the storm clouds of October. The crowd of more than 145,000 sang along with the band and cheered as the field rolled off behind the Stoddard-Dayton pace car.

From the start, Cliff Woodbury took command in his front-drive Miller, setting a blistering pace and leading the early stages. His front-drive configuration gave superior cornering stability, and he seemed poised to dominate—until disaster struck.

At lap 90, Woodbury’s car crashed violently in Turn 2 when the right rear tire failed, sending the car flipping end-over-end. Miraculously, he survived, but the incident served as a grim reminder of the razor’s edge between brilliance and catastrophe.

The crash reshuffled the field. Ray Keech, who had been running cautiously in third, assumed the lead as the Millers of Meyer and Shaw fell into mechanical trouble. Keech’s smooth consistency became his greatest asset: lap after lap, his rhythm never faltered.

The Final Miles

As the afternoon sun burned over the Speedway, Keech’s Miller purred like a clockwork instrument. His team, led by Klein and Rigling, executed flawless pitwork—fueling, oiling, and tire changes without a single delay.

Behind him, Lou Meyer clawed his way back into contention, but tire issues forced him to pit late. Floyd Roberts, in another Miller Special, pushed hard in the closing stages but could not catch the leader.

After 5 hours, 7 minutes, and 11 seconds, Ray Keech crossed the finish line to take victory, averaging 97.585 mph. His margin over second place was more than seven minutes—a commanding triumph born of patience and precision.

The victory capped a dazzling month for Keech, who earlier that spring had set a world land speed record of 207.55 mph on Daytona Beach, driving the monstrous 81-liter Triplex Special. Weeks later, the car would claim the life of Keech’s friend and rival, Lee Bible—a sobering counterpoint to Keech’s own success.

Aftermath and Legacy

Ray Keech’s 1929 victory was both a technical and symbolic milestone. It showcased the absolute dominance of Miller engineering—an era of mechanical artistry unmatched in motorsport. Yet it was also the end of innocence.

Just five months later, the Wall Street Crash of October 1929 plunged America into economic despair. Factory teams disbanded, sponsors vanished, and the Miller operation itself faced financial ruin. The golden glow of the Jazz Age Speedway dimmed almost overnight.

Keech, meanwhile, would enjoy only a fleeting reign. A year later, he was killed in a racing accident at Altoona Speedway, joining Lockhart and Boyer among the tragic pantheon of 1920s American heroes—drivers who defined the limits of their craft, and paid dearly for it.

Yet their work lived on. The 1929 race marked the final flourish of the pure Miller era—a moment when design, craftsmanship, and courage aligned to perfection.

Reflections

The 1929 Indianapolis 500 was the exclamation point at the end of an era. It was the last great spectacle of roaring engines and boundless optimism before the Great Depression transformed American motorsport forever.

Ray Keech’s smooth, composed drive reflected the wisdom of experience in a decade that had too often rewarded recklessness. His triumph was not only mechanical—it was philosophical. The 500 had matured from a contest of survival into a contest of judgment.

Under the brilliant Indiana sun of May 1929, the bricks sang their last song of the Jazz Age: bright, fearless, and fleeting.

Sources

Indianapolis Motor Speedway Archives — “Official Records of the 1929 International 500-Mile Sweepstakes” (IMS Heritage Collection)

Motorsport Magazine Archive — “Ray Keech and the Last Roar of the Twenties” (May 2029 Centennial Feature)

The Indianapolis Star, May 31 – June 1, 1929 — Race-day and post-race reports

Automobile Quarterly, Vol. 35, No. 1 (1997) — “Miller’s Final Triumph: The 1929 Indianapolis 500”

Harry A. Miller Papers, Los Angeles Public Library Collection

Smithsonian Institution — Transportation Collections: Miller 91 Specifications and 1929 Team Records

1930 Indianapolis 500 — The Boy Commander’s Total Triumph

Date: May 30, 1930

Circuit: Indianapolis Motor Speedway (2.5 mi oval, brick surface)

Distance: 500 miles (200 laps)

Entries: 38 starters (33 qualified)

Winner: Billy Arnold — Miller Special

Average Speed: 100.448 mph

Prelude to the Eighteenth Running

The 1930 Indianapolis 500 took place in a changed America. The roaring optimism of the 1920s had ended in the crash of October 1929, and the country was entering its darkest decade. But for one day each May, at the Brickyard, the noise of engines drowned out the silence of uncertainty.

Despite the Depression, the Miller dynasty remained at the heart of the sport. The cars were smaller, sleeker, and faster than ever. Privateer teams—many operating on razor-thin budgets—continued to run Miller machinery, often rebuilt and re-tuned from earlier seasons.

It was an age of survival through ingenuity, and no one embodied that better than Billy Arnold, a 24-year-old Chicago-born racer and mechanical engineer who would deliver one of the most dominant performances in Speedway history.

The Field and the Machines

By 1930, the technical landscape of Indianapolis had stabilized around Harry Miller’s engineering. His 91-cubic-inch straight-eights, often rebuilt or privately owned, filled nearly the entire grid. Duesenberg had largely exited the scene, and the new generation of builders—Rigling, Stevens, and Offenhauser—were keeping the Miller lineage alive.

Billy Arnold’s No. 4 Miller Special, entered by the Hartz-Miller team, featured a supercharged Miller 91 straight-eight, refined with improved lubrication and aerodynamics. It produced around 190 horsepower, capable of propelling the lightweight chassis past 120 mph on the straights.

Key competitors included:

Louis Meyer, 1928 champion, in a Miller Special.

Harry Hartz, team owner and veteran driver, also in a Miller.

Cliff Woodbury, in a front-drive Miller.

Shorty Cantlon, in a private Miller entry.

Though the Great Depression had thinned the factory budgets, the mechanical craftsmanship of these cars was still exquisite—the last breath of the golden age before austerity set in.

Race Day

The morning of May 30, 1930, dawned clear and mild. Attendance, while slightly lower than the boom years, remained strong—roughly 120,000 spectators filled the grandstands.

When the green flag fell, Billy Arnold leapt into the lead and immediately began setting a punishing pace. His car was perfectly balanced, its supercharger humming in rhythm with his steady, precise driving. By the 50-mile mark, Arnold had built a full lap’s advantage over the field.

As the day wore on, his dominance only grew. His pitwork was flawless—fuel, tires, and oil changes completed with military efficiency. Mechanics signaled him to slow down, but Arnold, calm and confident, maintained his rhythm. By the halfway point, he was two laps clear.

Behind him, Louis Meyer and Shorty Cantlon gave chase, but their efforts were futile. Arnold’s Miller was running in its own world—steady, smooth, untouchable.

The Final Miles

By lap 175, Billy Arnold had lapped the entire field twice. No one had ever done it before, and no one would do it again for more than three decades. His car ran faultlessly, his concentration unbroken.

With 10 laps to go, Meyer made a late surge, but Arnold’s lead was insurmountable. He cruised across the finish line after 4 hours, 58 minutes, and 30 seconds, at an average speed of 100.448 mph—becoming only the second driver in history to average over 100 mph for the full 500 miles.

It was a masterclass of domination: 198 of 200 laps led, the largest margin of superiority in Indianapolis history to that point.

Aftermath and Legacy

Billy Arnold’s 1930 performance instantly became the benchmark for Indianapolis greatness. Dubbed “The Boy Commander” by newspapers, he combined youthful confidence with mechanical precision, driving the perfect race in an imperfect world.

His triumph stood as a testament to Miller’s engineering and to the professionalism that now defined the event. In the depths of economic despair, Arnold’s victory was a symbol of progress and persistence—a reminder that excellence could endure even in hardship.

But Arnold’s reign would prove brief. A crash in 1931 ended his run while leading, and he retired from racing soon after. Yet his 1930 performance remained a model of efficiency—so complete that future champions like Meyer and Shaw would study it for years to come.

The race also marked a turning point for the Speedway. As the Depression deepened, the days of factory teams and gleaming Miller works cars faded. Builders like August Offenhauser and Leo Goossen—Miller’s disciples—would keep the flame alive, developing the next generation of engines that would dominate for decades.

Reflections

The 1930 Indianapolis 500 was a triumph of clarity in a time of chaos. It embodied the precision, discipline, and quiet genius of an era closing under the weight of history.

Billy Arnold’s wire-to-wire domination represented the final expression of the pure Miller age—a time when craftsmanship, courage, and calculation coexisted in perfect harmony.

In a decade soon defined by scarcity, the sight of Arnold’s silver Miller streaking alone across the bricks was a vision of perfection: fleeting, flawless, and unforgettable.

Sources

Indianapolis Motor Speedway Archives — “Official Records of the 1930 International 500-Mile Sweepstakes” (IMS Heritage Collection)

Motorsport Magazine Archive — “Billy Arnold and the Boy Commander’s Perfect Race” (May 2030 Centennial Feature)

The Indianapolis Star, May 31 – June 1, 1930 — Race-day and technical coverage

Automobile Quarterly, Vol. 36, No. 2 (1998) — “The End of the Miller Era: 1930 and Beyond”

Harry A. Miller & August Offenhauser Papers, Los Angeles Public Library & NAHC, Detroit

Smithsonian Institution — Transportation Collections: Miller 91 Supercharged Chassis Technical Notes

1931 Indianapolis 500 — When Fate Took the Wheel

Date: May 30, 1931

Circuit: Indianapolis Motor Speedway (2.5 mi oval, brick surface)

Distance: 500 miles (200 laps)

Entries: 40 starters (33 qualified)

Winner: Louis Meyer — Miller Special

Average Speed: 96.629 mph

Prelude to the Nineteenth Running

America in 1931 was deep in the Great Depression. The gleam of the Jazz Age had faded into dust, and racing—like every luxury—was struggling to survive. Yet on Memorial Day, the Speedway still drew more than 120,000 spectators. For a few hours, the thunder of the 500 offered escape from breadlines and layoffs.

Technically, the race remained a showcase for Harry Miller’s mechanical genius, even though Miller himself was bankrupt. His designs—rebuilt, re-tuned, and re-entered under private ownership—still dominated the field. August Offenhauser, Miller’s chief machinist, had quietly begun to build and maintain these engines in his own right, marking the first steps toward the legendary Offenhauser era.

Defending champion Billy Arnold, the “Boy Commander,” arrived as overwhelming favorite. His crushing 1930 win had set records, and his new car—an updated Miller Special with refined supercharger and improved aerodynamics—was the best in the field. But as history would soon prove, even perfection could be undone by fate.

The Field and the Machines

The grid of 1931 was a patchwork of Miller heritage. Nearly every entry was powered by a Miller or a derivative: supercharged 91s, modified 122s, and new “semi-stock” variations maintained by Offenhauser’s Los Angeles workshop.

Leading contenders:

Billy Arnold, defending champion, in the No. 1 Miller Special.

Louis Meyer, 1928 winner, driving a Miller-Offenhauser Special.

Shorty Cantlon, in a Miller Special.

Fred Frame, in a Bowes Seal Fast Special (Miller-powered).

Tony Gulotta, in a Cooper Miller.

The cars were smaller and lighter than ever before—barely 1,500 pounds—with engines producing between 180 and 200 horsepower. Top speeds approached 130 mph on the straights, but fragility remained their curse.

Race Day

Under warm skies and a brisk breeze, the 1931 race began at 10 a.m. sharp. At the drop of the green flag, Billy Arnold immediately surged to the front—just as he had the year before. His pace was mesmerizing: smooth, relentless, calculated. By lap 10, he was already lapping cars. By lap 40, he held a full lap lead.

His Miller ran perfectly, the supercharger whining with the same precision that had carried him to victory in 1930. The crowd buzzed; it seemed inevitable he would win again. Arnold led more than half the race—155 of 200 laps—at an average nearing 100 mph.

But destiny intervened. On lap 162, disaster struck. While overtaking slower traffic in Turn 3, Arnold’s right rear tire exploded. The car veered sharply into the outside wall, struck head-on, and flipped violently into the infield. Debris scattered across the bricks as the crowd gasped in horror.

Arnold was thrown clear but survived with severe injuries—a fractured skull and multiple broken bones. His riding mechanic, Spider Matlock, was also badly hurt. Their miraculous survival owed more to luck than to technology. The dominant champion was out, his car destroyed.

The Final Miles

With Arnold’s retirement, chaos reigned. The lead shuffled among Louis Meyer, Shorty Cantlon, and Tony Gulotta as attrition mounted. Tires shredded, magnetos failed, and oil lines ruptured in the heat.

Meyer, ever the tactician, stayed calm. He had driven carefully all afternoon, maintaining mechanical sympathy for his Miller-Offenhauser Special. As others faltered, his steady rhythm paid dividends. By lap 180, he held a solid lead.

In the closing miles, Gulotta’s Miller closed the gap, but a late pit stop ended his charge. Meyer cruised through the final laps at reduced pace, nursing his engine home. After 5 hours, 10 minutes, 42 seconds, he crossed the line first at an average of 96.629 mph, claiming his second Indianapolis 500 victory.

It was a triumph not of speed, but of restraint—exactly the kind of race that defined Louis Meyer’s career.

Aftermath and Legacy

The 1931 Indianapolis 500 marked both an ending and a beginning. Billy Arnold’s near-fatal crash ended the career of one of the most gifted drivers of the era; he never raced competitively again. His brief two-year reign had redefined dominance, but also reminded the sport of its fragility.

For Louis Meyer, the win cemented his reputation as the consummate professional: intelligent, patient, and mechanically attuned. He became the first repeat winner since Tommy Milton, and the embodiment of the new Depression-era racer—efficient, disciplined, and humble.

Technically, 1931 was the true dawn of the Offenhauser era. August Offenhauser’s meticulous rebuilds of Miller engines kept the field alive through the lean years, and his improvements in strength and lubrication would eventually birth the legendary “Offy” that ruled Indianapolis from the 1930s to the 1970s.

Reflections

The 1931 Indianapolis 500 was a race of survival and symbolism. It began as a repeat of the previous year’s perfection and ended as a testament to endurance over brilliance.

It was the moment when the myth of invincibility—the idea that sheer speed could conquer all—finally shattered. In its place arose a new philosophy: that the 500 was not a sprint of strength, but a test of control, intelligence, and grace under pressure.

Amid a nation in hardship, Louis Meyer’s calm victory and Billy Arnold’s fall mirrored America itself—resilient, wounded, but still moving forward.

Sources

Indianapolis Motor Speedway Archives — “Official Records of the 1931 International 500-Mile Sweepstakes” (IMS Heritage Collection)

Motorsport Magazine Archive — “Louis Meyer and the Fall of Billy Arnold” (May 2031 Centennial Feature)

The Indianapolis Star, May 31 – June 1, 1931 — Race-day and accident coverage

Automobile Quarterly, Vol. 37, No. 2 (1999) — “Meyer, Arnold, and the Turning Point of the 500”

Harry Miller / August Offenhauser Papers, Los Angeles Public Library and National Automotive History Collection

Smithsonian Institution — Transportation Collections: Miller 91 and Miller-Offenhauser Engineering Documentation