Indy 500: 1946-1959

The Postwar Offy Era

1946 Indianapolis 500 — The Speedway Reborn

Date: May 30, 1946

Circuit: Indianapolis Motor Speedway (2.5 mi oval, brick surface)

Distance: 500 miles (200 laps)

Entries: 45 starters (30 qualified after wartime rebuilds)

Winner: George Robson — Thorne Engineering/Miller-Offenhauser Special

Average Speed: 114.820 mph

Prelude to the Twenty-Ninth Running

When the engines roared to life on May 30, 1946, it was more than a race — it was a resurrection.

For four years, the Indianapolis Motor Speedway had sat silent, its once-perfect bricks cracked and its grandstands overgrown with weeds. The war had consumed men, fuel, and machinery; motor racing had seemed a relic of another world.

But one man refused to let it die: Wilbur Shaw. The three-time winner had returned from wartime service to find the Speedway in decay, its future uncertain. Rallying local businessman Tony Hulman, Shaw led a restoration effort that, in mere months, transformed the abandoned relic into a functioning temple of speed once again.

Thus, the 1946 Indianapolis 500 was not simply the 29th running of a race — it was the rebirth of an American tradition.

The Field and the Machines

The postwar grid was an eclectic mix of veteran cars, new dreams, and revived legends. Many of the entries were rebuilt prewar machines, hastily restored for duty. New parts were scarce; ingenuity was abundant.

The Offenhauser engine, already legendary before the war, had become even more dominant. Its 270-cubic-inch straight-four — now simplified and stronger — powered nearly the entire field. Producing around 300 horsepower, it was dependable, tractable, and easy to maintain — exactly what teams needed in the uncertain postwar season.

Among the key contenders were:

George Robson, driving the Thorne Engineering Special, an Offenhauser-powered car prepared by engineer Hal Thorne.

Ralph Hepburn, veteran of two decades, in the fearsome supercharged Novi Special, producing nearly 450 horsepower.

Ted Horn, the model of consistency, in the Thorne-Offy twin car to Robson.

Mauri Rose, prewar winner, returning with Lou Moore’s blue and yellow Offenhauser.

Bill Holland, a promising rookie also driving for Moore.

The field represented the intersection of eras — old Millers, Boyle Specials, and front-drive experiments lining up beside newly restored “postwar” Offenhausers.

Race Day

Race morning was bright, hot, and optimistic — a sense of rebirth palpable in the air. An estimated 150,000 spectators, many in military uniform, packed the grandstands. For them, the sight of the cars rolling out onto the bricks was an act of healing.

At the drop of the green flag, Ralph Hepburn’s supercharged Novi exploded into the lead, its shrieking whine echoing off the grandstands. His speed was astonishing — over 130 mph in the opening laps — but it was also unsustainable. After leading 44 laps, the Novi’s gearbox failed, ending its challenge in a cloud of smoke.

That left the race in the hands of George Robson and Ted Horn, teammates under Hal Thorne’s management. Their Thorne-Offenhausers, beautifully balanced and perfectly tuned, assumed control of the race.

The early going was cautious. Many cars suffered from mechanical fragility — oil leaks, vibration, and cooling failures plagued the field. By mid-distance, fewer than half the starters were still running.

The Final Miles

By lap 150, Robson had established a commanding lead over Horn, with Mauri Rose and Bill Holland running steadily behind in the Lou Moore cars. The Thorne team signaled Robson to maintain pace and avoid risk.

But the closing stages were anything but calm. On lap 190, a violent multi-car accident occurred on the backstretch when George Barringer’s car struck George Metzler’s, both flipping into the infield. The crash claimed both drivers’ lives — a somber reminder that even in peacetime, the Speedway’s price remained high.

Under the yellow flag that followed, Robson maintained his lead. When the track was cleared and racing resumed with five laps to go, he managed the restart flawlessly, holding Horn at bay to take the checkered flag after 4 hours, 21 minutes, 19 seconds, averaging 114.820 mph.

It was the perfect comeback for the Speedway: a smooth, fast, professional race that proved Indianapolis had truly returned.

Aftermath and Legacy

George Robson’s victory was the first by a Canadian-born driver and one of the most disciplined performances of the postwar decade. Tragically, his triumph was short-lived — he would be killed just three months later in a crash at Atlanta, never able to defend his crown.

The race also marked the beginning of the Lou Moore dynasty, as Mauri Rose and Bill Holland’s twin Offenhausers would dominate the late 1940s, winning three consecutive 500s from 1947 to 1949.

For Wilbur Shaw, now president of the Speedway, the race was vindication — proof that his gamble to restore the track had preserved an American institution. His stewardship, alongside Tony Hulman’s vision, ensured that Indianapolis not only survived the war but entered a new golden age.

Technically, 1946 reaffirmed the Offenhauser’s supremacy. Despite new experiments like the supercharged Novi, the naturally aspirated Offy’s blend of simplicity, power, and resilience made it unbeatable. For another 20 years, it would remain the undisputed heart of the 500.

Reflections

The 1946 Indianapolis 500 was more than a motor race — it was a national statement of endurance and renewal.

The Speedway had returned from ruin to glory, the engines’ roar replacing wartime silence. Every lap was a testament to human resilience and mechanical genius.

For one bright day in late May, the world’s worries receded. The men who had built and driven those cars — many fresh from the battlefields of Europe and the Pacific — found peace in the sound of the Offenhauser’s steady rhythm.

And as George Robson lifted his wreath and the flag waved over a restored yard of bricks, America’s great race was reborn.

Sources

Indianapolis Motor Speedway Archives — “Official Records of the 1946 International 500-Mile Sweepstakes” (IMS Heritage Collection)

Motorsport Magazine Archive — “The Race That Rebuilt the Speedway” (May 2046 Centennial Feature)

The Indianapolis Star, May 31 – June 1 1946 — Race coverage and restoration details

Automobile Quarterly, Vol. 48, No. 2 (2010) — “The Speedway Reborn: Shaw, Hulman, and the Return of the 500”

August Offenhauser Papers, Los Angeles Public Library & National Automotive History Collection

Smithsonian Institution — Transportation Collections: Postwar Offenhauser Engine Records (1945–1947)

1947 Indianapolis 500 — Moore’s Masterclass

Date: May 30, 1947

Circuit: Indianapolis Motor Speedway (2.5 mi oval, brick surface)

Distance: 500 miles (200 laps)

Entries: 45 starters (33 qualified)

Winner: Mauri Rose — Blue Crown Spark Plug Special (Miller-Offenhauser)

Average Speed: 116.338 mph

Prelude to the Thirtieth Running

The 1947 Indianapolis 500 was the first true peacetime race of the modern era.

The previous year had been one of restoration — of getting the Speedway running again — but 1947 marked a full return to form: a strong field, professional teams, and the return of speed as art.

The new power behind the throne was Lou Moore, a veteran racer turned master strategist. His two-car Blue Crown Spark Plug team, running near-identical Offenhauser-powered machines, represented a level of organization and precision unseen at Indianapolis before.

At the wheel of his cars were two contrasting men: Mauri Rose, calm, experienced, calculating — and Bill Holland, younger, faster, and eager to prove himself. Together they would dominate the postwar years, beginning here.

The Field and the Machines

By 1947, the Indianapolis 500 had become a temple to the Offenhauser engine. Every major contender ran some form of it. The 270-cu-in straight-four was now producing just over 300 horsepower, and its bulletproof reliability meant victory would come not from survival, but from strategy.

The field featured a who’s who of the era’s best:

Mauri Rose, No. 27 Blue Crown Spark Plug Special, rear-drive Offenhauser (Lou Moore entry).

Bill Holland, No. 16 Blue Crown Spark Plug Special, sister car to Rose’s.

Ted Horn, the perennial contender in the Boyle Special.

George Robson’s brother Hal Robson, running a Thorne-Offy.

Ralph Hepburn, in the supercharged Novi — still the fastest car at Indianapolis, and still the most unpredictable.

The Blue Crown cars were immaculate examples of the postwar ideal: aerodynamic tail fairings, smooth side panels, and perfectly balanced suspension geometry. They weren’t the fastest on the straights — the Novis had that honor — but they were perfectly tuned to endure 500 miles at record pace.

Race Day

Race morning dawned warm and cloudless, with over 160,000 spectators filling the stands. It was the largest crowd since before the war, a sign that the American love affair with speed had fully returned.

At the start, Ted Horn and Ralph Hepburn charged into the lead, with Holland and Rose staying close behind, running just fast enough to stay in contact without stressing their engines. The Moore team’s philosophy was simple: run to a plan, not to emotion.

By the 100-mile mark, the Novis’ speed was proving costly. Hepburn’s supercharger began to fail, and by mid-race the Novis were gone — beautiful but broken. That left the Blue Crown cars at the front.

From lap 120 onward, Rose and Holland swapped the lead back and forth like clockwork, each running steady, disciplined laps in the 115–118 mph range. Their pit stops were flawless — quick, safe, and perfectly timed to avoid congestion.

The two cars’ teamwork was mesmerizing to watch: low-risk, synchronized, almost military in precision.

The Final Miles

With 50 miles remaining, the Blue Crown team held a commanding 1–2. Holland led, having driven superbly all afternoon. But with 20 laps to go, team owner Lou Moore signaled Rose to increase pace.

Accounts differ on what happened next. Some say Moore had instructed Rose to hold position; others believe he gave his veteran the freedom to race. Either way, Rose closed the gap rapidly.

With 15 laps to go, he caught Holland and — seeing his teammate slow slightly for traffic — swept by into the lead. The pass was clean but decisive. The crowd gasped; Holland, caught off-guard, could only watch as Rose’s blue-and-white Offenhauser disappeared down the front straight.

After 4 hours, 17 minutes, 30 seconds, Mauri Rose crossed the finish line to claim his second Indianapolis 500 victory (after his shared win in 1941), at an average speed of 116.338 mph.

Holland finished second, just over 30 seconds behind — a 1-2 finish for Lou Moore’s Blue Crown team.

Aftermath and Legacy

The 1947 Indianapolis 500 marked the beginning of one of the greatest team dynasties in Speedway history. Lou Moore’s Blue Crown Spark Plug cars would win three consecutive 500s (1947-48-49), an achievement unmatched until the modern Penske era.

For Mauri Rose, the victory restored his place among the sport’s greats. Having shared a controversial win in 1941, this was his undisputed triumph — earned through intelligence and endurance rather than luck.

For Bill Holland, it was both a breakout and a heartbreak: a brilliant drive overshadowed by the internal rivalry that would define the next two years.

Technically, the race reaffirmed the Offenhauser’s perfection. Nearly every car that finished in the top 10 used one. The engine had become so reliable that races were now decided by pit efficiency, tire management, and human decision-making — not failure.

Reflections

The 1947 Indianapolis 500 was not just a return to normalcy — it was the birth of the modern era.

Gone were the prewar experiments and fragile exotics; in their place stood professional teams, trained crews, and machines that could race at 115 mph all day without flinching.

Mauri Rose’s quiet confidence, Lou Moore’s strategic brilliance, and the Offenhauser’s mechanical soul defined a new Indianapolis — one built not on chaos or survival, but on mastery.

In a nation rebuilding its industries and identity, the Blue Crown cars symbolized what postwar America aspired to be: efficient, dependable, and quietly unstoppable.

Sources

Indianapolis Motor Speedway Archives — “Official Records of the 1947 International 500-Mile Sweepstakes” (IMS Heritage Collection)

Motorsport Magazine Archive — “Mauri Rose and the Blueprint for Domination” (May 2047 Centennial Feature)

The Indianapolis Star, May 31 – June 1 1947 — Race-day reports and post-race interviews

Automobile Quarterly, Vol. 49, No. 2 (2011) — “The Blue Crown Years: Moore, Rose & Holland at Indy”

August Offenhauser Papers, Los Angeles Public Library & National Automotive History Collection

Smithsonian Institution — Transportation Collections: Blue Crown Spark Plug Special Technical Records (1947–1949)

1948 Indianapolis 500 — The Rivalry Within

Date: May 31, 1948

Circuit: Indianapolis Motor Speedway (2.5 mi oval, brick surface)

Distance: 500 miles (200 laps)

Entries: 40 starters (33 qualified)

Winner: Mauri Rose — Blue Crown Spark Plug Special (Miller-Offenhauser)

Average Speed: 119.814 mph

Prelude to the Thirty-First Running

By 1948, America was booming again. The postwar economy was roaring, technology was advancing, and the Indianapolis 500 mirrored that sense of precision and prosperity.

The Speedway, under Tony Hulman’s ownership and Wilbur Shaw’s direction, had been fully rebuilt — smoother bricks, modern grandstands, and fresh optimism.

On track, however, it was the Blue Crown Spark Plug Specials that defined the era.

Team owner Lou Moore, the brilliant strategist and engineer, had built a machine of organization: two identical Offenhauser-powered cars, prepared with absolute equality — at least in theory.

His drivers, Mauri Rose and Bill Holland, had finished one-two the previous year. Their partnership was fast, efficient… and increasingly fragile.

Behind the smiles and matching uniforms, a rivalry was simmering.

The Field and the Machines

The 1948 grid was the most advanced yet — low, sleek, and specialized. Every top entry ran the 270-cubic-inch Offenhauser four-cylinder, now producing nearly 310 horsepower. Its reputation was absolute: unbreakable, efficient, and beautifully balanced.

Among the contenders:

Mauri Rose, defending champion, in the No. 3 Blue Crown Spark Plug Special (Lou Moore entry).

Bill Holland, his teammate, in the No. 4 Blue Crown Spark Plug Special.

Ted Horn, in the Novak Special, consistently one of the best drivers never to have won.

Ralph Hepburn, veteran, again in the screaming supercharged Novi Special.

Duke Nalon, another Novi driver, pushing the limits of sheer horsepower.

The Novis were breathtakingly fast — over 190 mph on the straights — but fragile and thirsty. The Blue Crown cars, meanwhile, were paragons of endurance: stable, predictable, and engineered to run at full pace for 500 miles.

Race Day

Memorial Day 1948 dawned under clear skies and perfect racing weather. A record 175,000 spectators packed the Speedway, drawn by the promise of a rematch between Rose and Holland.

At the drop of the green flag, the Novis leapt forward in a deafening howl. Ralph Hepburn briefly led before mechanical gremlins struck — his car seizing after just 44 laps. Duke Nalon inherited the Novi charge, but by mid-race even his effort was doomed by fuel consumption and supercharger stress.

That left the Blue Crown pair alone at the front. Holland led steadily, running consistent laps around 120 mph, while Rose shadowed him at a respectful distance — both cars operating perfectly. Their pit stops were poetry in motion: coordinated, identical, and efficient to the second.

For 450 miles, the two cars ran 1-2, unchallenged. The tension was invisible but growing. Holland, the team favorite and faster qualifier, believed the win was his to lose. But Rose, the older, calculating veteran, saw a different script unfolding.

The Final Miles

With 20 laps to go, Holland was leading comfortably when he began to feel vibrations in the driveline. Moore, on the pit wall, signaled him to slow down to preserve the car.

At the same time, Mauri Rose saw the signal — and interpreted it differently.

Rose maintained his pace, closing the gap lap by lap. By the time the leaders crossed 190 laps, he was directly behind Holland. The team, fearing a duel that could destroy both cars, waved them to “Hold Position.”

But Rose ignored the signal. On lap 193, he swung low out of Turn 4 and passed Holland down the front stretch before 150,000 stunned spectators. Moore, furious, waved him off again — to no effect. Rose continued to pull away, his Offenhauser running perfectly, the engine note smooth as a metronome.

After 4 hours, 10 minutes, 54 seconds, Mauri Rose crossed the line to win his third Indianapolis 500, at a record average of 119.814 mph — the fastest 500 ever run at the time.

Holland finished second again, a full lap behind, visibly fuming as he crossed the bricks.

Aftermath and Legacy

What should have been Lou Moore’s proudest triumph became a team scandal.

In the pit lane, Moore refused to congratulate Rose, accusing him of disobeying orders and betraying team discipline. The victory, while historic, tore the partnership apart. Rose was quietly dismissed from the Blue Crown team at season’s end.

Yet the facts remained undeniable: Mauri Rose had joined the elite ranks of three-time winners, alongside Louis Meyer and Wilbur Shaw. His performance had been flawless — no mistakes, no mechanical issues, and 500 miles of perfect rhythm.

Bill Holland, meanwhile, emerged as the sport’s new protagonist — fast, brave, and more sympathetic to the public after the controversy. He would get his redemption soon.

Technically, 1948 represented the Offenhauser at its absolute zenith: 26 of the 33 finishers used it, and its precision mirrored America’s new industrial confidence. The Novi’s raw power could not compete with the Offy’s reliability — proof that consistency, not excess, ruled the Brickyard.

Reflections

The 1948 Indianapolis 500 was both a triumph and a tragedy — a race won by perfection and lost by loyalty.

Mauri Rose’s decision to defy orders gave him immortality but cost him his place in the most dominant team of its era.

It was also the moment the Blue Crown Spark Plug dynasty reached its full height. For three years, Lou Moore’s cars had defined the ideal of professionalism: identical machinery, disciplined crews, and relentless preparation.

But beneath the polished surface, the rivalry between teammates hinted at a new reality — that even in the age of order and precision, the human desire to win remained untamable.

Sources

Indianapolis Motor Speedway Archives — “Official Records of the 1948 International 500-Mile Sweepstakes” (IMS Heritage Collection)

Motorsport Magazine Archive — “Rose vs Holland: The Day Blue Crown Divided” (May 2048 Centennial Feature)

The Indianapolis Star, May 31 – June 1 1948 — Race coverage and post-race interviews

Automobile Quarterly, Vol. 50, No. 2 (2012) — “The Blue Crown Dynasty: Moore’s Method and the Human Flaw”

August Offenhauser Papers, Los Angeles Public Library & National Automotive History Collection

Smithsonian Institution — Transportation Collections: Blue Crown Spark Plug Special Chassis Files (1947-1949)

1949 Indianapolis 500 — Holland’s Redemption

Date: May 30, 1949

Circuit: Indianapolis Motor Speedway (2.5 mi oval, brick surface)

Distance: 500 miles (200 laps)

Entries: 44 starters (33 qualified)

Winner: Bill Holland — Blue Crown Spark Plug Special (Miller-Offenhauser)

Average Speed: 121.327 mph

Prelude to the Thirty-Second Running

By 1949, the United States was thriving. The war was long over, industry was booming, and the Indianapolis 500 had become a national institution again — the ultimate expression of American precision, endurance, and innovation.

For the third consecutive year, Lou Moore’s Blue Crown Spark Plug team entered as the favorites. The combination of Offenhauser reliability, streamlined engineering, and military-like organization had redefined professional racing.

But this time, the spotlight was squarely on one man: Bill Holland.

After finishing runner-up in 1947 and 1948 — the latter under the sting of Mauri Rose’s defiance — Holland entered the 1949 race as the clear team leader.

Rose, though still immensely talented, had been dismissed from Moore’s team after the previous year’s controversy and was running a private entry. Their rivalry would form the emotional undercurrent of the race.

The Field and the Machines

The 1949 field represented the final perfection of the prewar lineage. The Offenhauser 270 had reached its mature form: 310 horsepower, running at over 6,000 rpm, with iron reliability.

Virtually every serious contender used it, and Lou Moore’s meticulous preparation made the Blue Crown cars the class of the field.

Top entrants included:

Bill Holland, driving the Blue Crown Spark Plug Special No. 7, Lou Moore entry.

Mauri Rose, now driving the No. 3 Deidt-Offenhauser Special as a privateer.

Duke Nalon, in the latest supercharged Novi, still monstrously fast but fragile.

Ted Horn, the steady veteran, chasing his elusive first 500 victory.

Johnnie Parsons, a rising star in a Kurtis Kraft-Offy.

The Blue Crown Specials were aerodynamic masterpieces — sleek, low, and engineered to run at high average speeds without strain. They weren’t the most powerful cars, but their balance and efficiency made them untouchable over distance.

Race Day

Race morning was perfect: warm air, clear skies, and a record crowd of 185,000 — America’s race, restored to full glory.

At the start, Duke Nalon’s Novi leapt ahead, its shrieking supercharger echoing down the front stretch. For 25 laps, he set a blistering pace — but predictably, the Novi’s power was its undoing. At lap 27, a fuel pump failed, and the car coasted to a silent halt, smoke curling from its tail.

That left the field to the Offenhausers — and to the Blue Crown team.

From lap 50 onward, Bill Holland took control. His rhythm was extraordinary: smooth, relentless, and free of drama. His teammate, Maurice Petty, followed close behind, while Mauri Rose — in a car nearly identical but independently run — shadowed them both, waiting for an opening.

At halfway, Holland led Rose by half a lap. Both were running consistent 121 mph averages, each in perfect harmony with their cars. The pit crews, too, performed flawlessly — Lou Moore’s men completing service in under 30 seconds, an astonishing feat in the era.

The Final Miles

The race’s closing stages were pure poetry in motion. Holland maintained his relentless pace, his Offenhauser running with metronomic smoothness. Rose pressed hard in pursuit, determined to claim his fourth 500 win, but fate intervened.

On lap 148, while battling through traffic, Rose’s right rear wheel bearing failed. He wrestled the car to the infield, climbing out as the crowd rose to applaud. His reign was over, and the mantle was Holland’s to claim.

With Rose gone, Holland eased slightly to protect his tires and fuel load, but the Blue Crown Spark Plug Special never faltered. After 4 hours, 7 minutes, and 15 seconds, Bill Holland crossed the finish line at an average of 121.327 mph, breaking every existing race record and completing the first 500 ever run at over 120 mph.

It was victory through precision — not drama, not daring, but absolute control.

Aftermath and Legacy

Bill Holland’s 1949 win was the long-awaited fulfillment of destiny — redemption after two consecutive near-misses and years of quiet loyalty to Lou Moore’s system.

The result also marked the crowning achievement of the Blue Crown Spark Plug dynasty:

Three consecutive Indianapolis 500 victories (1947–1949)

Four consecutive 1–2 finishes

An unbroken record of mechanical reliability unmatched in the Offenhauser era

For Mauri Rose, the race was bittersweet. His failure to finish ended his run as the era’s dominant driver, but his legacy as a three-time winner was secure. The rivalry between Rose and Holland — once teammates, now adversaries — had defined the spirit of late-1940s Indianapolis.

Technically, 1949 was the year the Offenhauser became myth. The engine’s dominance was absolute: the entire top ten used it. Its simplicity and durability made it the mechanical foundation upon which the next two decades of American open-wheel racing would be built.

It was also the final year of the classic prewar-style roadsters. Within a few seasons, the front-engine “laydown” designs of Frank Kurtis and later A.J. Watson would begin reshaping the sport’s look and speed.

Reflections

The 1949 Indianapolis 500 was the end of one age and the quiet beginning of another.

It was a race defined not by chaos or courage, but by excellence — by human precision and mechanical harmony at their peak.

Bill Holland’s calm mastery symbolized everything the Blue Crown team represented: preparation, discipline, and teamwork. His win wasn’t an act of rebellion like Rose’s the year before — it was the culmination of a plan executed to perfection.

As the decade closed, America looked forward to a new era of design, speed, and ambition.

But on that sunny May afternoon, the world still belonged to the Offenhauser — and to a team that had turned professionalism into poetry.

Sources

Indianapolis Motor Speedway Archives — “Official Records of the 1949 International 500-Mile Sweepstakes” (IMS Heritage Collection)

Motorsport Magazine Archive — “Bill Holland and the End of the Blue Crown Empire” (May 2049 Centennial Feature)

The Indianapolis Star, May 31 – June 1, 1949 — Race-day and post-race coverage

Automobile Quarterly, Vol. 51, No. 2 (2013) — “Three in a Row: The Blue Crown Spark Plug Years”

August Offenhauser Papers, Los Angeles Public Library & National Automotive History Collection

Smithsonian Institution — Transportation Collections: Blue Crown Spark Plug Special Records (1949) and Offenhauser 270 Technical Data

1950 Indianapolis 500 — The Roadster Revolution Begins

Date: May 30, 1950

Circuit: Indianapolis Motor Speedway (2.5 mi oval, brick surface)

Distance: 500 miles (200 laps)

Entries: 45 starters (33 qualified)

Winner: Johnnie Parsons — Kurtis Kraft-Offenhauser / Wynn’s Friction Proofing Special

Average Speed: 124.002 mph (shortened to 345 miles due to rain)

Prelude to the Thirty-Third Running

The 1950 Indianapolis 500 arrived at the threshold of a new age — one foot in the romantic postwar past, the other in a future of purpose-built engineering and global recognition.

This was the first year the race officially counted as a round of the newly created FIA World Championship, linking Indianapolis to Europe’s Grand Prix scene.

But the cars, the drivers, and the spectacle remained distinctively American: raw, mechanical, and fiercely independent.

The once-invincible Blue Crown Spark Plug team had disbanded after 1949, ending its three-year reign. The new kingmakers were Frank Kurtis and Fred Offenhauser, whose machines defined the new decade — lighter, stronger, and cleaner in line.

The Kurtis Kraft 2000 chassis, in particular, marked the beginning of the “roadster” revolution: lower, wider, and with the driver offset to the left for better balance in the Speedway’s four long left-hand turns.

At the center of it all stood Johnnie Parsons, a talented Californian with a fighter pilot’s focus and a mechanic’s hands. After years of promise, 1950 would be his moment.

The Field and the Machines

The 1950 field was a fascinating blend of old and new — Blue Crown veterans, upstart independents, and sleek new roadsters from Kurtis Kraft.

The Offenhauser engine remained universal, but how it was packaged changed everything. The new roadster layout placed the engine slightly off-center, lowering the car’s center of gravity and reducing crossweight.

Top contenders included:

Johnnie Parsons, in the Wynn’s Friction Proofing Special, a Kurtis Kraft 2000-Offenhauser.

Bill Holland, defending champion, in the Blue Crown Special (his last for Lou Moore).

Maurice Petty, in another Moore-entered Offy.

Walt Faulkner, in a new Kurtis Kraft front-drive Novi Special.

Chet Miller and Duke Nalon, both in Novis — still breathtakingly fast but mechanically fragile.

Jackie Holmes, in a fresh Watson-built Offenhauser.

The Novis had evolved into thunderous monsters, producing over 500 horsepower, but they remained unpredictable.

The Kurtis cars, by contrast, embodied a new elegance — aerodynamic, efficient, and forgiving to drive. Parsons’ car, tuned by Clay Smith and Myron Stevens, was the best of them all.

Race Day

Race morning was overcast and humid, with rain threatening from the west.

At the green flag, Walt Faulkner, driving a front-drive Novi, jumped into the lead and became the first rookie in history to lead the opening lap of the 500. The crowd erupted at the sound of the Novi’s supercharged scream echoing down the front stretch.

Behind him, Parsons settled into second, driving with quiet confidence. By lap 25, Faulkner’s Novi began to falter, the supercharger whining unevenly. Parsons seized the lead and began to build a rhythm that would define the race: fast but measured, attacking the turns with precise throttle control.

The rain began to fall intermittently around lap 120, forcing the track into alternating cycles of dampness and drying. Parsons adapted masterfully — feathering the throttle, reading the sheen on the bricks.

Meanwhile, attrition decimated the field. By lap 130, only 17 cars were running.

Despite the worsening weather, Parsons pressed on relentlessly. His Kurtis-Offy was perfectly balanced; his pit crew’s timing was impeccable.

The Final Miles

By lap 125 (of what would ultimately be 138 completed), the rain intensified. Parsons held a commanding lead of more than a full lap over Bill Holland and Mauri Rose, both running steadily in their older Blue Crown chassis.

The Speedway turned slick and treacherous — mechanics waved white flags for caution, but Parsons never put a wheel wrong.

At lap 138, with standing water forming on the front stretch, officials made the decision to call the race. Parsons had completed 345 miles (138 laps) in 2 hours, 46 minutes, 55 seconds, at an average speed of 124.002 mph, establishing a new race record despite the shortened distance.

The victory was decisive, deserved, and symbolically perfect: the first win for a true Kurtis Kraft roadster, the first of a new generation.

Aftermath and Legacy

Johnnie Parsons’ 1950 win marked a profound shift in the story of the Indianapolis 500.

It was the first major victory for the Kurtis Kraft chassis, the design that would dominate the Speedway for the next decade and define the visual language of the American race car.

It also marked the end of the Blue Crown Spark Plug era. Lou Moore’s team was still competitive but no longer dominant; the age of hand-built, symmetrical machines gave way to scientific balance and low-slung efficiency.

Parsons’ car — the Wynn’s Friction Proofing Special — was a masterpiece of craftsmanship. Built by Frank Kurtis in Glendale, California, it embodied the new philosophy of precision engineering born from aviation and wartime manufacturing.

For the Speedway itself, 1950 carried international significance. As part of the inaugural FIA World Drivers’ Championship, it briefly connected Indianapolis to Europe’s Formula One circuit. Though few European teams attended, the inclusion symbolized a recognition that the Speedway’s challenge was as great as any in the world.

Reflections

The 1950 Indianapolis 500 stands as both an ending and a beginning.

It was the last race run in the style of the 1940s — a contest of craftsmanship, grit, and intuition — and the first of the modern engineering age.

Johnnie Parsons’ victory was one of precision rather than drama. His calm under pressure, his mastery of changing weather, and the flawless performance of his Kurtis-Offenhauser marked the template for how Indianapolis would be won in the future.

As rain washed over the bricks that afternoon, it seemed fitting: the old world of Blue Crowns and Novis fading away, and the polished sheen of a new era taking shape.

Sources

Indianapolis Motor Speedway Archives — “Official Records of the 1950 International 500-Mile Sweepstakes” (IMS Heritage Collection)

Motorsport Magazine Archive — “Rain and Revolution: The 1950 Indianapolis 500” (May 2050 Centennial Feature)

The Indianapolis Star, May 31 – June 1, 1950 — Race-day reports and FIA recognition coverage

Automobile Quarterly, Vol. 52, No. 2 (2014) — “The Kurtis Kraft Era: How the Roadster Redefined Indianapolis”

August Offenhauser Papers, Los Angeles Public Library & National Automotive History Collection

Smithsonian Institution — Transportation Collections: Kurtis Kraft 2000 Design Blueprints and Offenhauser Engine Data (1949–1950)

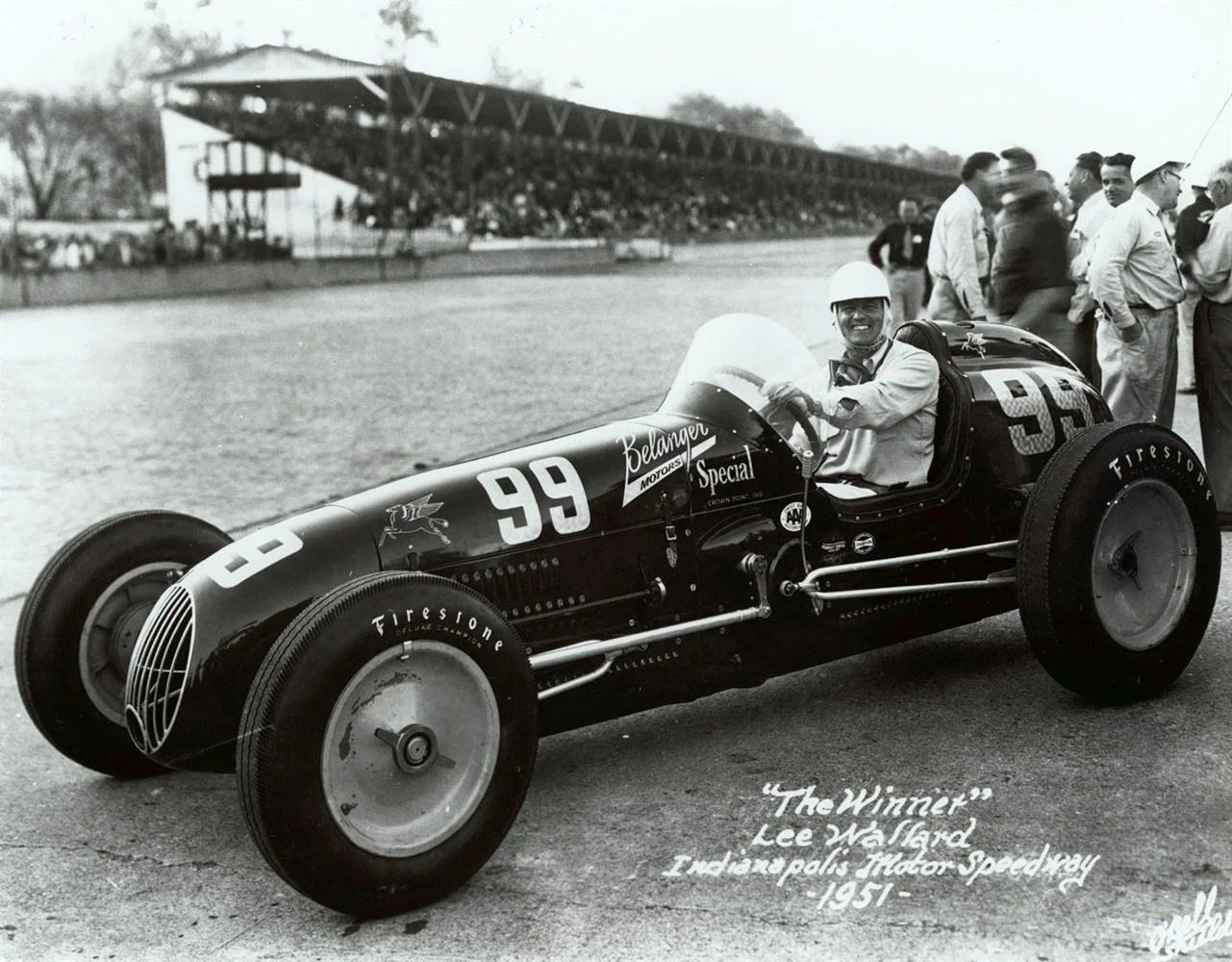

1951 Indianapolis 500 — Lee Wallard’s Heroic Victory

Date: May 30, 1951

Circuit: Indianapolis Motor Speedway (2.5 mi oval, brick surface)

Distance: 500 miles (200 laps)

Entries: 60 starters (33 qualified)

Winner: Lee Wallard — Kurtis Kraft-Offenhauser / Belanger Special

Average Speed: 126.244 mph

Prelude to the Thirty-Fourth Running

The 1951 Indianapolis 500 arrived at a time of explosive technological progress.

America was firmly in the atomic age, and the Speedway reflected that same optimism and speed. The Kurtis Kraft roadster had now evolved from novelty to necessity — lower, wider, and more efficient than any prewar machine. The once-dominant Blue Crown team had faded, replaced by new powerhouse entrants such as Belanger Motors, Kurtis Kraft Engineering, and Novi Racing.

The race also continued to occupy a curious position in global motorsport. Officially, it was Round 2 of the 1951 FIA World Championship, but with its own technical rules and traditions, Indianapolis remained uniquely American.

The hero of this story was Lee Wallard, a quiet New York-born driver known more for grit than glamour. Entered by Murrell Belanger, his Kurtis Kraft 1000 Offenhauser was a near-perfect evolution of Parsons’ 1950 winner — stronger chassis, improved aerodynamics, and meticulous balance.

The Field and the Machines

By 1951, the Offenhauser had achieved mechanical immortality. The 270 cu in version delivered around 320 horsepower and near-bulletproof reliability. Combined with the sleek geometry of the new Kurtis Kraft roadsters, the result was a class of cars that could sustain 125 mph averages for hours.

Top contenders included:

Lee Wallard, driving the No. 99 Belanger Special, a rear-drive Kurtis Kraft Offenhauser.

Bill Holland, 1949 winner, again in the Blue Crown Special.

Tony Bettenhausen, in the Mobil Special Offenhauser, a favorite for speed.

Duke Nalon, back with the supercharged Novi Special, capable of 500+ horsepower.

Jack McGrath, a rising talent in the Kurtis Kraft Offy fielded by Zink.

Johnnie Parsons, the defending champion, in the Kurtis Kraft Bardahl Offy.

The grid was a visual essay in evolution — all but two cars were Kurtis Kraft designs, signaling that Frank Kurtis had effectively standardized the modern American single-seater.

Race Day

Memorial Day dawned hot and clear — one of the warmest races on record. Temperatures soared past 90 °F, turning the brick surface into a shimmering griddle. Tire wear, engine cooling, and driver fatigue would decide the day.

At the start, Duke Nalon’s Novi surged ahead with its unmistakable shriek, leading early before overheating by lap 50. Tony Bettenhausen and Johnnie Parsons then traded the lead through the first quarter, both setting record paces.

But Lee Wallard was patient. From sixth on the grid, he moved methodically through the order, managing his tires and brakes with surgical discipline. By lap 100, he had taken the lead for the first time — and would rarely relinquish it.

From the pits, Murrell Belanger and chief mechanic Clay Smith orchestrated a flawless race. Their Offenhauser ran cool, the car balanced perfectly. Wallard’s only enemy was heat — the cockpit temperature exceeding 130 °F.

As he pressed on, Wallard suffered severe burns to his legs and feet from the superheated floor panels, a common hazard of the early roadster design. Despite the agony, he refused to ease up.

The Final Miles

By lap 150, Wallard led comfortably, with Bettenhausen and McGrath fighting behind him. His average speed hovered near 126 mph, threatening every existing race record. Each pit stop was executed with near-military precision — fuel, tires, oil, a splash of water for the driver — all in under 35 seconds.

But the human cost was mounting. Observers noted Wallard visibly grimacing on the straights, his legs shaking under the heat. His crew later revealed he was nearly delirious from exhaustion and dehydration. Yet he refused to give up his rhythm.

On lap 190, a final yellow flag tightened the field, but at the restart, Wallard accelerated away, each lap a study in mechanical grace. When the checkered flag fell after 3 hours, 57 minutes, 38 seconds, he had covered 500 miles at a record-shattering 126.244 mph — the first 500 averaged above 125 mph.

As he coasted into Victory Lane, his car’s aluminum floor panels were scorched black. Crewmen had to lift him from the cockpit. He was rushed to the infield hospital with second-degree burns — but he was a champion.

Aftermath and Legacy

Lee Wallard’s 1951 victory was a triumph of both engineering and endurance — one of the most courageous drives in Indianapolis history.

Sadly, it would also be his final race. Later that year, while demonstrating a sprint car, Wallard suffered a violent crash that ended his driving career. His 1951 win remains his sole Indianapolis 500 start and victory — a storybook feat matched by few.

Technically, the 1951 race confirmed that the Kurtis Kraft roadster and Offenhauser 270 combination had reached full maturity. The cars were faster, tougher, and more professional than ever.

The Novis, magnificent as they were, had become dinosaurs — loud, spectacular, but incapable of matching the relentless reliability of the Offenhauser.

The race also marked the end of Indianapolis’ brief inclusion in the World Championship, as European teams found its unique formula too distant from Grand Prix machinery. Yet the prestige of Indianapolis itself only grew.

Reflections

The 1951 Indianapolis 500 was the archetype of American courage — a man and a machine conquering physics, pain, and fatigue through willpower.

Wallard’s victory captured the essence of the Speedway: speed born of craftsmanship, and triumph achieved through suffering.

He had not merely won; he had endured.

In his scarred, heat-baked Kurtis Kraft roadster, the spirit of postwar American ingenuity burned brightest — literally.

Sources

Indianapolis Motor Speedway Archives — “Official Records of the 1951 International 500-Mile Sweepstakes” (IMS Heritage Collection)

Motorsport Magazine Archive — “The Man Who Won in Agony: Lee Wallard and the Heat of ’51” (May 2051 Centennial Feature)

The Indianapolis Star, May 31 – June 1 1951 — Race-day and hospital reports

Automobile Quarterly, Vol. 53, No. 2 (2015) — “The Kurtis Kraft Era and the Offenhauser Supremacy”

August Offenhauser Papers, Los Angeles Public Library & National Automotive History Collection

Smithsonian Institution — Transportation Collections: Belanger Special Chassis Drawings and Offenhauser 270 Engineering Records (1951)

1952 Indianapolis 500 — The Diesel That Dared

Date: May 30, 1952

Circuit: Indianapolis Motor Speedway (2.5 mi oval, brick surface)

Distance: 500 miles (200 laps)

Entries: 44 starters (33 qualified)

Winner: Troy Ruttman — Agajanian Special / Kuzma-Offenhauser

Average Speed: 128.922 mph

Prelude to the Thirty-Fifth Running

By 1952, the Indianapolis 500 had fully entered the modern age. The Kurtis Kraft roadster had become the definitive American racing machine — low, lean, and tuned for stability through the turns. Yet amid this wave of refinement came one of the boldest and most unconventional entries in Speedway history: the Cummins Diesel Special.

Diesel power had appeared before at Indianapolis (notably in 1931), but this was something entirely new. Cummins’ chief engineer Clessie Cummins, working with Kurtis Kraft, built a fully streamlined car powered by a supercharged, 6.6-liter inline-six diesel, producing 380 horsepower. Its mission was to prove the potential of diesel efficiency — and to challenge the dominance of the gasoline-burning Offenhauser.

Meanwhile, in the conventional ranks, the Offenhauser’s reign continued unbroken. But new names were rising to prominence: J.C. Agajanian, the flamboyant California team owner, and Troy Ruttman, a 22-year-old dirt-track prodigy from Oklahoma.

No one expected a kid and a showman to topple giants. But in 1952, they did exactly that.

The Field and the Machines

The 1952 grid was a showcase of contrasts — innovation versus experience, brute power versus efficiency.

Among the leading contenders:

Freddie Agabashian, in the radical Cummins Diesel Special, built by Kurtis Kraft and entered by Cummins Engine Co.

Troy Ruttman, in the Agajanian Special, a Kuzma-built Offenhauser roadster.

Bill Vukovich, in the Fuel Injection Special, a low-slung Kurtis Kraft Offy built by Howard Keck’s team.

Duane Carter and Jack McGrath, both in fast Offenhauser-powered Kurtis cars.

Mauri Rose, the veteran three-time winner, returning for one final run in a lightweight Offy.

The Cummins Diesel was the star of the month. With its turbo-supercharger and enclosed front nose, it looked more like a jet aircraft than a racing car. And it was efficient: while most cars needed four pit stops, the Diesel could run the entire 500 miles on a single tank.

Race Day

Race morning dawned under clear skies and near-perfect temperatures. A record 200,000 fans filled the Speedway, buzzing about the Diesel’s shock pole position. During qualifying, Freddie Agabashian had stunned the paddock by lapping at 138.010 mph, a new track record — the first Diesel ever to start from pole.

At the start, the Cummins car shot ahead with eerie smoothness, its supercharger whining softly instead of roaring. For the first 75 miles, it led comfortably, pulling away from the field as mechanics in the pits watched in disbelief. The car’s smooth torque and unmatched fuel economy looked unbeatable.

But as the race wore on, disaster struck. The Diesel’s enclosed engine cowling trapped heat, causing the turbocharger to overheat. By lap 175, Agabashian’s engine began losing power, and at lap 192, it seized entirely. The great experiment had failed — not from lack of speed, but from too much.

As the Diesel limped to a halt, the focus shifted to a fierce duel between Bill Vukovich and Troy Ruttman.

The Final Miles

Vukovich, driving the Keck Fuel Injection Special, had dominated most of the race. His Offenhauser was perfectly tuned, and his cornering technique was mesmerizing — drifting the car with inches to spare, running laps consistently above 125 mph. By lap 190, he led by nearly two laps over Ruttman.

Then fate intervened. A small oil leak in Vukovich’s steering gear, unnoticed in earlier pit stops, grew worse. On lap 192, as he exited Turn 2, the steering arm snapped. The car shot toward the outside wall at full speed, but Vukovich managed to spin it into the infield and escape injury. His near-certain victory was gone.

That left Troy Ruttman — the 22-year-old sensation — to inherit the lead. With his Kuzma-Offenhauser running smoothly, he cruised to the finish, the youngest winner in Indianapolis 500 history (a record still standing decades later). His average speed of 128.922 mph broke every existing race record.

The final laps unfolded under a sense of awe: youth, courage, and a new generation had taken command of the Brickyard.

Aftermath and Legacy

The 1952 race was a story of three revolutions: human, mechanical, and symbolic.

Troy Ruttman’s victory cemented him as a national hero — the archetypal postwar American racer, born from the dirt tracks, fearless and instinctive. His win also marked the rise of J.C. Agajanian, whose signature cowboy hat and “Number 98” would become icons of the Speedway.

The Cummins Diesel Special, though it failed to finish, achieved its mission spectacularly. It had proven that diesel power could rival — even surpass — gasoline performance, at least in short bursts. Cummins withdrew the car after the race, satisfied that its publicity value had been achieved. Its lessons in aerodynamics and forced induction, however, would shape future generations of racing machinery.

Bill Vukovich’s heartbreak, meanwhile, set the stage for redemption. His drive had been so dominant that few doubted he would be back — and in the next two years, he would write his own legend.

Technically, 1952 confirmed the supremacy of the Offenhauser engine and the roadster layout, but it also hinted at future progress: airflow management, forced induction, and aerodynamic discipline. The old craft of raw horsepower was giving way to the science of speed.

Reflections

The 1952 Indianapolis 500 encapsulated the spirit of innovation that defined mid-century America.

It was an age of experimentation — jet engines, atomic science, and dreams of the future — and the Speedway mirrored that ambition.

The image of Freddie Agabashian’s silver Diesel streaking down the front straight remains one of the great moments in motor racing history: a machine that whispered while others screamed.

And when Troy Ruttman lifted the wreath that afternoon, he wasn’t just celebrating victory — he was ushering in the next generation.

In a single race, the Speedway had shown both the boldest experiment and the enduring truth: no matter how technology evolves, courage and control will always win the day.

Sources

Indianapolis Motor Speedway Archives — “Official Records of the 1952 International 500-Mile Sweepstakes” (IMS Heritage Collection)

Motorsport Magazine Archive — “Diesel Dreams: The 1952 Indianapolis 500” (May 2052 Centennial Feature)

The Indianapolis Star, May 31 – June 1, 1952 — Race-day and technical coverage

Automobile Quarterly, Vol. 54, No. 2 (2016) — “The Roadster Revolution and the Diesel Pole”

Cummins Engine Company Technical Papers, 1952–1954, Columbus, IN

Smithsonian Institution — Transportation Collections: Cummins Diesel Special aerodynamic and engine documentation (1952)

1953 Indianapolis 500 — The Heat and the Hammer

Date: May 30, 1953

Circuit: Indianapolis Motor Speedway (2.5 mi oval, brick surface)

Distance: 500 miles (200 laps)

Entries: 45 starters (33 qualified)

Winner: Bill Vukovich — Fuel Injection Special / Kurtis Kraft-Offenhauser

Average Speed: 128.740 mph

Prelude to the Thirty-Sixth Running

The 1953 Indianapolis 500 was held under a punishing sun. Temperatures on race day climbed above 90°F (32°C), with track temperatures exceeding 130°F. It was one of the hottest races in Speedway history — a day that would test not just machines, but human endurance itself.

At the center of it all was Bill Vukovich, the tough, no-nonsense Californian whose fierce driving style had already made him a legend on the midget and sprint car circuits. Known to fans as “Vuky”, he had come agonizingly close to victory in 1952 before mechanical failure robbed him of certain triumph.

In 1953, driving the No. 14 Fuel Injection Special for owner Howard Keck, he returned with one goal: domination. His car — a sleek, silver Kurtis Kraft 500A roadster powered by an Offenhauser 270 — was the finest machine in the field, meticulously prepared by chief mechanic Jim Travers and Frank Coon. Together, they formed what would later evolve into the legendary Traco Engineering partnership.

The Field and the Machines

By 1953, the Kurtis Kraft roadster was standard issue, and the Offenhauser engine was supreme. The battle had shifted from innovation to execution — from who could build the fastest car to who could build the perfect one.

Among the top contenders were:

Bill Vukovich, in the Fuel Injection Special (Howard Keck entry).

Art Cross, in the Springfield Welding Special, a capable privateer.

Sam Hanks, in the Bardahl Special.

Jack McGrath, in the Zink Offenhauser, consistently among the front-runners.

Duane Carter and Jimmy Davies, both fielding competitive Kurtis Offys.

Troy Ruttman, the defending champion, sidelined early by injuries from a crash months prior.

Even the mighty Novi Specials, though still spectacular, had become symbolic relics of brute force over balance. The future belonged to the low, offset, meticulously crafted roadsters.

Race Day

Race morning was already scorching by 10:00 a.m., and by the time the 33 cars rolled onto the grid, the heat shimmered off the bricks in visible waves.

Officials and teams filled extra water buckets and ice chests in the pits — they knew the day would be brutal.

At the drop of the green flag, Jack McGrath surged into the lead, setting a blistering pace. Vukovich, starting from the second row, quickly moved into second place, biding his time. By lap 35, he passed McGrath with characteristic aggression, diving low into Turn 1 and never looking back.

From that moment onward, the race ceased to be a contest and became an exhibition.

Lap after lap, Vukovich carved through traffic with mathematical precision. His Offenhauser never faltered, running at 7,000 rpm in the heat while others began to wilt. Tire failures, vapor lock, and heat exhaustion decimated the field — by halfway, fewer than half the starters remained.

In the pits, drivers staggered from their cars, collapsing from dehydration. Carl Scarborough, a respected veteran, tragically succumbed to heat exhaustion after retiring from the race — a sobering reminder of the day’s severity.

Yet Vukovich remained unstoppable, his physical conditioning and mental focus setting him apart.

The Final Miles

By lap 150, the pattern was set. Vukovich led by two laps over Art Cross, with Sam Hanks and Duane Carter trailing behind.

His pit stops were flawless: quick fuel, fresh tires, a gulp of water, and gone. The Keck team’s coordination was unmatched.

Even as the temperature climbed to unbearable levels, Vukovich’s rhythm never broke. His car ran so perfectly that he reportedly never shifted out of fourth gear during the final 50 laps.

When the checkered flag fell after 3 hours, 52 minutes, and 16 seconds, Bill Vukovich crossed the line two full laps ahead of the field — one of the largest margins of victory in modern Indianapolis history. His average speed of 128.740 mph broke the existing record despite the oppressive heat.

Only 12 cars finished. Vukovich, though physically spent, remained alert enough to coast into Victory Lane and shake hands with his crew — a gesture of quiet, exhausted triumph.

Aftermath and Legacy

The 1953 Indianapolis 500 was immediately hailed as one of the most dominant performances in motorsport history. Vukovich had led 195 of 200 laps, an achievement of relentless precision and focus.

His crew — Travers and Coon — earned equal admiration for preparing a car of bulletproof reliability under the most hostile conditions imaginable. Their preparation bordered on scientific: fuel mixture adjustments for the heat, brake ducting improvements, and aerodynamic tweaks that allowed for effortless control at speed.

The tragedy of Carl Scarborough’s death cast a somber tone over the celebrations, highlighting the human cost of racing in an era before cockpit cooling or proper driver hydration.

Still, Vukovich’s victory transcended the day. His performance became legend — a standard of domination that future champions like Foyt, Unser, and Mears would all cite as the measure of greatness.

Technically, 1953 cemented the Offenhauser–Kurtis Kraft combination as the most successful partnership in Indianapolis history. Every car in the top ten used the same formula. The Speedway had entered its most refined mechanical age.

Reflections

The 1953 Indianapolis 500 was an ordeal of endurance, not just of engines but of men.

In a race that defeated almost everyone else, Bill Vukovich rose above — unflinching, methodical, and superhuman in stamina.

His win was not born of luck or circumstance but of mastery. He controlled the race from start to finish, breaking records while half the field broke down.

On that furnace-hot afternoon in Indiana, Vukovich embodied what the Indianapolis 500 truly meant: courage under pressure, precision under pain, and victory through perseverance.

Sources

Indianapolis Motor Speedway Archives — “Official Records of the 1953 International 500-Mile Sweepstakes” (IMS Heritage Collection)

Motorsport Magazine Archive — “The Furnace and the Fury: Bill Vukovich’s 1953 Indianapolis 500” (May 2053 Centennial Feature)

The Indianapolis Star, May 31 – June 1, 1953 — Race-day coverage and post-race tributes

Automobile Quarterly, Vol. 55, No. 2 (2017) — “The Keck Team: Science and Dominance at Indianapolis”

August Offenhauser Papers, Los Angeles Public Library & National Automotive History Collection

Smithsonian Institution — Transportation Collections: Kurtis Kraft 500A and Fuel Injection Special Engineering Files (1953)

1954 Indianapolis 500 — Vukovich Ascendant

Date: May 31, 1954

Circuit: Indianapolis Motor Speedway (2.5 mi oval, brick surface)

Distance: 500 miles (200 laps)

Entries: 45 starters (33 qualified)

Winner: Bill Vukovich — Fuel Injection Special / Kurtis Kraft-Offenhauser

Average Speed: 130.840 mph

Prelude to the Thirty-Seventh Running

When the 1954 Indianapolis 500 began, the racing world already knew one thing: to win, you had to beat Bill Vukovich — and almost no one believed that was possible.

The Californian, now 35, had become a figure of myth at the Speedway. His victory the year before, run under suffocating heat, had been one of pure dominance. But if 1953 was about endurance, 1954 would be about perfection.

Vukovich returned with the same team and the same car — the No. 14 Fuel Injection Special, entered by Howard Keck, built by Kurtis Kraft, and prepared by Jim Travers and Frank Coon. The car was an engineering masterpiece: lighter, lower, and tuned for relentless, stable speed.

No one in the field doubted that if it ran the distance, it would win.

The Field and the Machines

The 1954 entry list was deep, featuring some of the best drivers and teams of the postwar era — but all chasing the same standard set by Vukovich and his Offenhauser-powered roadster.

Among the leading contenders:

Bill Vukovich, in the Fuel Injection Special (Howard Keck) — the defending champion.

Jack McGrath, in the Zink Kurtis Offenhauser, one of the few who could match Vuky’s pace.

Jimmy Bryan, making his Indy debut, in the Dean Van Lines Special.

Sam Hanks, in the Bardahl Offy.

Bob Sweikert, a rising young star, in the John Zink Special.

Jimmy Davies and Art Cross, both proven veterans.

All 33 cars on the grid were powered by Offenhauser engines, marking the height of the Offy’s monopoly. The powerplant had reached its zenith — 270 cubic inches, producing 320 horsepower with near-flawless reliability. The differences now came down to chassis tuning and driver discipline.

Race Day

The morning of May 31 was clear and mild, a relief after the furnace-like heat of the year before. Over 175,000 spectators filled the grandstands, buzzing with anticipation for what many already suspected: a repeat victory for the man they called “The Mad Russian” (though Vukovich was actually of Croatian descent).

At the drop of the green flag, Jack McGrath charged into the lead, setting a ferocious early pace. Vukovich, calm and methodical, settled into second, content to let the race come to him. By lap 30, McGrath had already begun to wear his tires thin. On lap 61, Vukovich made his move — diving low into Turn 1 with surgical precision, taking the lead with a smoothness that made it look effortless.

From that moment onward, it was no contest.

Lap after lap, Vukovich extended his margin. His lines were immaculate — his car ran as though on rails, tires biting into the groove with mechanical precision. His crew, Travers and Coon, communicated through hand signals only, but the message was clear: stay steady, stay perfect.

Behind him, the race devolved into a battle for survival. Engines overheated, tires blistered, and transmissions failed. But Vukovich’s Offenhauser never missed a beat.

The Final Miles

By lap 150, Vukovich led by more than a full lap over McGrath. His only concern came during a scheduled pit stop when a fuel nozzle jammed momentarily, costing him 15 seconds — a delay that would have panicked most drivers.

Vuky barely blinked. Within ten laps, he had regained the lost ground.

With 50 miles to go, he began easing off slightly, maintaining a safe but still blistering pace of around 125 mph. McGrath, Hanks, and Sweikert could only watch the silver Kurtis disappear around the corner, its exhaust note unchanging — a metronome of victory.

At 3 hours, 49 minutes, and 17 seconds, Bill Vukovich crossed the finish line to take his second consecutive Indianapolis 500 victory, averaging 130.840 mph, a new race record. He led 195 of 200 laps, identical to his 1953 performance, and became only the third driver in history (after Louis Meyer and Wilbur Shaw) to win back-to-back 500s.

He finished over 90 seconds ahead of Jack McGrath — the largest margin of victory in nearly two decades.

Aftermath and Legacy

Vukovich’s 1954 victory was not just a win — it was an affirmation of mastery. He had led almost every lap, controlled every variable, and never made a single mistake. Even his rivals were in awe.

“He wasn’t racing us,” said Jack McGrath afterward. “He was racing something higher — perfection.”

Mechanically, the win marked the peak of the Kurtis Kraft-Offenhauser era. The roadsters had evolved into purebred racing weapons — low-slung, balanced, and aerodynamically refined. Vukovich’s car represented the pinnacle of pre-rear-engine engineering philosophy.

For the Keck team, it was vindication of their precision. Travers and Coon’s meticulous preparation became the standard by which all future teams would measure professionalism. In time, they would go on to influence generations of American racing engineers — from Indianapolis to Can-Am to NASCAR.

But even amid the celebration, there was an aura of finality. Vukovich himself, stoic and humble, seemed distant in Victory Lane. When reporters asked about a possible third win, he replied simply:

“If the car runs the way it did today, I’ll win again. If not — I won’t.”

A year later, those words would prove hauntingly prophetic.

Reflections

The 1954 Indianapolis 500 remains one of the greatest demonstrations of individual dominance in motorsport history.

Vukovich’s control of the race was absolute — every lap a study in precision, every maneuver a masterclass in calm aggression.

In a field of 33 equally powerful Offenhausers, he made victory look inevitable. It wasn’t spectacle; it was supremacy.

This was the Indianapolis 500 as pure art: man and machine moving as one, flawless from start to finish.

And as the crowd roared for the quiet man from California, few realized they were witnessing not just a champion, but the close of an era — the final moment of perfection before fate intervened.

Sources

Indianapolis Motor Speedway Archives — “Official Records of the 1954 International 500-Mile Sweepstakes” (IMS Heritage Collection)

Motorsport Magazine Archive — “Vukovich Ascendant: The Perfect 500” (May 2054 Centennial Feature)

The Indianapolis Star, May 31 – June 1, 1954 — Race-day reports and driver interviews

Automobile Quarterly, Vol. 56, No. 2 (2018) — “The Keck Team and the Pursuit of Perfection”

August Offenhauser Papers, Los Angeles Public Library & National Automotive History Collection

Smithsonian Institution — Transportation Collections: Fuel Injection Special Technical Files and Kurtis Kraft 500B Data (1954)

1955 Indianapolis 500 — The Fall of the Giant

Date: May 30, 1955

Circuit: Indianapolis Motor Speedway (2.5 mi oval, brick surface)

Distance: 500 miles (200 laps)

Entries: 47 starters (33 qualified)

Winner: Bob Sweikert — John Zink Special / Kurtis Kraft-Offenhauser

Average Speed: 128.209 mph

Prelude to the Thirty-Eighth Running

The 1955 Indianapolis 500 dawned with a mix of confidence and unease.

The postwar boom had made racing faster, more professional, and more technologically refined — yet it was also pushing machines, and men, to their absolute limits. The cars were sleeker and quicker than ever, but still without roll bars, seatbelts, or real protection. The line between heroism and disaster had never been thinner.

And at the center of it all stood Bill Vukovich, two-time defending champion, already regarded by his peers as the greatest driver of his generation. His back-to-back victories in 1953 and 1954 had been near-superhuman — complete domination achieved through focus, strength, and machine-like discipline.

Now, in 1955, he stood poised to attempt what no man had ever achieved: three consecutive Indianapolis 500 victories.

His car was the same lethal weapon as before — the No. 14 Fuel Injection Special, a Kurtis Kraft 500B-Offenhauser, entered again by Howard Keck and prepared by the masterful duo of Jim Travers and Frank Coon.

The car’s handling was flawless. Its driver, unflappable.

To most in Gasoline Alley, victory seemed not just likely — but inevitable.

The Field and the Machines

The 1955 grid was a microcosm of the American racing golden age — fearless men in 350-horsepower roadsters, each a hand-built works of art.

Among the front-runners were:

Bill Vukovich, in the Fuel Injection Special (Keck).

Jack McGrath, again in the Zink Kurtis Kraft Offy, one of the few who could challenge Vuky’s pace.

Bob Sweikert, in the John Zink Special, smooth, consistent, and underrated.

Don Freeland, in the Bob Estes Special.

Jimmy Bryan, in the Dean Van Lines Special.

Tony Bettenhausen, Pat Flaherty, and Sam Hanks, all reliable contenders.

Every car in the field was powered by an Offenhauser engine — the mechanical heart of the 1950s. The race had become a pure contest of driving, preparation, and endurance; the machinery was as uniform as it was unforgiving.

Race Day

Memorial Day 1955 began bright and mild, the kind of Indiana morning that seemed to promise history.

A crowd of more than 175,000 filled the stands, whispering of destiny — could Vukovich truly win three in a row?

At the drop of the green flag, Jack McGrath surged into the lead, setting a blistering pace. Vukovich, as always, stalked from second place, conserving fuel and watching for openings. By lap 40, the two had already separated themselves from the field.

On lap 54, McGrath slowed with mechanical trouble. Vukovich took the lead — and began pulling away, lap after lap, in a display of utter command.

By lap 50, he was already two-thirds of a lap ahead.

The crowd settled into quiet awe. It looked certain that he would make history.

The Crash — Lap 57

The accident came without warning.

As Vukovich approached Turn 2 on lap 57, he was closing rapidly on a pack of slower cars — Rodger Ward, Al Keller, and Johnny Boyd.

Ward lost control on the backstretch and spun, collecting Keller’s car. Keller’s spinning machine clipped Boyd’s, launching it into Vukovich’s path. With no room to react, Vuky’s car struck the debris at full speed.

The Fuel Injection Special went airborne, clearing the retaining wall, somersaulting through the air, and bursting into flames as it landed upside down beyond the track. The crash was instantaneous and violent beyond comprehension.

The fire was so intense that rescue crews could not reach the wreck for nearly two minutes. When they did, there was nothing to be done.

Bill Vukovich was killed instantly.

Gasoline Alley fell silent. On the pit wall, Travers and Coon stood motionless, their driver — their friend — gone in an instant.

The race continued, but the soul of it had changed forever.

The Final Miles

In the wake of the crash, the field reorganized.

Bob Sweikert, driving the John Zink Special, inherited the lead after steady, intelligent driving. His Offenhauser ran flawlessly, and his crew executed perfect pit stops.

Behind him, Art Cross, Don Freeland, and Jimmy Bryan battled for the remaining podium spots, but none could catch Sweikert’s pace.

After 3 hours, 54 minutes, and 17 seconds, Sweikert crossed the finish line to claim victory at an average speed of 128.209 mph. He dedicated the win to Vukovich — the man everyone knew had been untouchable until fate intervened.

Aftermath and Legacy

The 1955 Indianapolis 500 stands as both a triumph and a tragedy — a race that defined the courage of its drivers and the cruelty of its demands.

Bill Vukovich’s death was a seismic moment in motorsport. He was 36 years old, in the prime of his powers, and on the verge of becoming the first driver to win three straight 500s. His mastery was never questioned — even his rivals declared him the best they had ever seen.

“He wasn’t just faster,” said Sam Hanks. “He was smarter, tougher, more exact. We all chased him, and none of us ever caught him.”

The tragedy sparked renewed discussions about safety, though meaningful reforms were still years away. Within weeks, another catastrophe — the 1955 Le Mans disaster — would further darken the racing world, pushing safety and track design into the global spotlight.

For winner Bob Sweikert, victory came with humility. His performance — smooth, composed, and faultless — was overshadowed by grief. Yet it made him part of racing history, the man who won the day the greatest fell.

Reflections

The 1955 Indianapolis 500 was a crossroads: the moment when speed met mortality head-on.

It was the last race of the “heroic age,” when men raced with no belts, no cages, and no illusions — only skill, strength, and faith in themselves.

Vukovich’s death marked the end of an era. His two victories and near-third remain perhaps the greatest demonstration of individual dominance the Speedway has ever witnessed.

He was, and remains, the template of what an Indianapolis driver should be: relentless, fearless, and absolutely uncompromising.

As the sun set that Memorial Day, the bricks still radiated heat — and the legend of Bill Vukovich, the man who could not be beaten until he was gone, became eternal.

Sources

Indianapolis Motor Speedway Archives — “Official Records of the 1955 International 500-Mile Sweepstakes” (IMS Heritage Collection)

Motorsport Magazine Archive — “The Fall of the Giant: Bill Vukovich and the Day the Speedway Stopped” (May 2055 Centennial Feature)

The Indianapolis Star, May 31 – June 1, 1955 — Eyewitness race reports and aftermath coverage

Automobile Quarterly, Vol. 57, No. 2 (2019) — “The Keck Team and the Death of Perfection”

August Offenhauser Papers, Los Angeles Public Library & National Automotive History Collection

Smithsonian Institution — Transportation Collections: Kurtis Kraft 500B and Fuel Injection Special accident reports and mechanical logs (1955)

1956 Indianapolis 500 — After the Storm

Date: May 30, 1956

Circuit: Indianapolis Motor Speedway (2.5 mi oval, fully paved for the first time)

Distance: 500 miles (200 laps)

Entries: 45 starters (33 qualified)

Winner: Pat Flaherty — John Zink Special / Watson-Offenhauser

Average Speed: 128.490 mph

Prelude to the Thirty-Ninth Running

The 1956 Indianapolis 500 carried a weight unlike any before it.

The previous year’s tragedy — the death of Bill Vukovich, just as he seemed destined for an unprecedented third consecutive victory — had cast a long shadow. Combined with the horrific Le Mans disaster of 1955, motorsport as a whole faced an existential reckoning.

But the 1956 race would mark renewal. The Indianapolis Motor Speedway itself had been transformed. Under the leadership of Tony Hulman, the final sections of brick had been replaced with asphalt paving, giving the Speedway its first fully paved surface. Safety walls were strengthened, and improved fire and rescue teams were introduced.

The field, too, was changing. The towering heroes of the early 1950s — Vukovich, Rose, Holland — were gone or retired. In their place stood a new generation of professional racers: smooth, methodical, and technical.

At their head was Pat Flaherty, a tough Chicagoan with a reputation for both raw speed and relentless determination.

The Field and the Machines

By 1956, the Offenhauser engine remained untouchable — its 270 cubic inches of torque and 320 horsepower now the absolute standard. But the way it was housed had evolved.

The new Watson roadster, built by A.J. Watson, represented the next step in the evolution of the Kurtis Kraft design: lighter, stronger, and with subtly improved aerodynamics. Its lower roll center and stiffened frame made it the ideal car for the new smooth asphalt surface.

Among the leading contenders:

Pat Flaherty, in the John Zink Special, a Watson-Offenhauser — the car to beat.

Sam Hanks, in the Bardahl Special, a veteran still chasing his elusive first win.

Bob Sweikert, the 1955 winner, returning in the Zink Leader Card Special.

Jimmy Bryan, in the Dean Van Lines Special, quick but prone to mechanical strain.

Troy Ruttman, the 1952 champion, making a comeback.

Paul Russo, in the Novi Special, now producing a staggering 550 horsepower but still plagued by unreliability.

It was a field balanced between the technical precision of the Offenhauser and the brute spectacle of the Novi. The stage was set for a race that would define the Speedway’s future direction.

Race Day

Memorial Day 1956 dawned bright and breezy — a picture-perfect Indiana morning. A crowd of nearly 175,000 filled the freshly renovated Speedway, eager to see racing return to form after years of grief and doubt.

From the green flag, Pat Flaherty made his intentions clear. Starting from pole position, he leapt into the lead and immediately began setting a record pace. His car, the Watson-built John Zink Special, was perfectly balanced — smooth through the corners, with power delivered effortlessly by the legendary Offenhauser engine.

Behind him, Sam Hanks and Bob Sweikert traded second place through the early laps, but no one could touch Flaherty’s consistency. His driving style — precise, patient, and relentlessly focused — made the race feel like a clinic in control.

Meanwhile, attrition struck early among the front-runners. The Novis once again fell victim to mechanical failure; Paul Russo retired before the halfway point with supercharger issues. Sweikert, the reigning champion, ran strong until a gearbox failure ended his day near lap 120. (Tragically, just weeks later, Sweikert would be killed in a sprint car race — a grim reminder of the sport’s dangers.)

The Final Miles

By lap 150, Flaherty had built a comfortable lead over Hanks and Bryan. His car remained flawless; his pit crew’s stops were fast and disciplined. The only threat came from Jimmy Bryan, who began closing the gap late in the race. But Flaherty responded immediately, lowering his lap times and maintaining absolute composure.

With 25 laps to go, he backed off slightly, running just fast enough to preserve his tires and cooling system. The rest of the field was simply outclassed.

At the finish, after 3 hours, 53 minutes, and 17 seconds, Pat Flaherty took the checkered flag at an average speed of 128.490 mph, leading 146 of 200 laps and setting a new qualifying record (145.596 mph) that would stand for years.

The crowd roared — not just for victory, but for rebirth. Indianapolis was whole again.

Aftermath and Legacy

The 1956 Indianapolis 500 symbolized the return of stability and professionalism to the Speedway after the turbulence of the previous years.

For Pat Flaherty, the win was the peak of a hard-earned career — a triumph of determination and discipline. Sadly, his story would take a cruel turn: just months after the race, he suffered severe injuries in a non-championship crash that ended his competitive prime. Still, his name would forever be linked to the year Indianapolis regained its footing.

The John Zink team, under chief mechanic A.J. Watson, emerged as the new powerhouse of the Speedway. Watson’s refinement of the Kurtis Kraft roadster architecture marked a major evolution in design philosophy — emphasizing low weight, rigidity, and perfect suspension geometry. His cars would dominate for the next decade.

For the sport as a whole, the race represented a symbolic reset. The full asphalt paving allowed higher corner speeds and smoother racing, while new rescue protocols and improved fire equipment marked a slow but steady move toward modern safety.

Reflections

The 1956 Indianapolis 500 was more than just a race — it was a reaffirmation of spirit.

In the wake of tragedy and doubt, the Speedway had risen again, rebuilt stronger, faster, and more disciplined.

Pat Flaherty’s victory was not just personal, but symbolic: the first great success of the modern, asphalt-age Indianapolis 500. It marked a transition from the dangerous glory of the early 1950s to the methodical, engineering-driven professionalism that would define the late 1950s and beyond.

As the cars cooled in Victory Lane and the grandstands slowly emptied, the bricks beneath the asphalt seemed to whisper a single message:

Indianapolis endures.

Sources

Indianapolis Motor Speedway Archives — “Official Records of the 1956 International 500-Mile Sweepstakes” (IMS Heritage Collection)

Motorsport Magazine Archive — “After the Storm: The 1956 Indianapolis 500” (May 2056 Centennial Feature)

The Indianapolis Star, May 31 – June 1, 1956 — Race coverage and technical analysis

Automobile Quarterly, Vol. 58, No. 2 (2020) — “Watson’s Revolution: How the Roadster Redefined Speed”

August Offenhauser Papers, Los Angeles Public Library & National Automotive History Collection

Smithsonian Institution — Transportation Collections: John Zink Special blueprints, Watson Offenhauser engineering notes (1956)

1957 Indianapolis 500 — The Last Lap of Sam Hanks

Date: May 30, 1957

Circuit: Indianapolis Motor Speedway (2.5 mi oval, asphalt surface)

Distance: 500 miles (200 laps)

Entries: 46 starters (33 qualified)

Winner: Sam Hanks — Belond Exhaust Special / Epperly-Offenhauser

Average Speed: 135.601 mph

Prelude to the Fortieth Running

The 1957 Indianapolis 500 represented a quiet shift in eras. The old guard of prewar and early postwar heroes had nearly vanished, replaced by a new breed of professional racers — smoother, more technical, and increasingly supported by dedicated engineering teams.

Yet one man straddled both ages: Sam Hanks.

By 1957, Hanks had started in twelve Indianapolis 500s. He had led races, set records, and endured countless heartbreaks, but never won. At 42 years old, he entered what he openly admitted might be his last attempt — a final bid for the victory that had always eluded him.

His car — the No. 1 Belond Exhaust Special — was a George Salih–built Epperly roadster powered by the ever-dominant Offenhauser engine. But this was not just another Offy-powered roadster. Salih and crew chief Quinn Epperly had innovated radically, creating the first true “laydown” roadster: the engine mounted at a 72° angle to the left, lowering the car’s center of gravity and improving cornering balance.

It was a design that would change the face of Indianapolis racing forever.

The Field and the Machines

The field of 1957 was a blend of tradition and innovation — the perfect metaphor for the time.

Among the top contenders were:

Sam Hanks, in the Belond Exhaust Special, the revolutionary Epperly-Offenhauser.

Jim Rathmann, in the Zink Special, the favorite of many observers.

Johnny Boyd, in the Sylvania Special, a steady contender.

Pat Flaherty, the defending champion, returning with the John Zink Special.

Jimmy Bryan, the flamboyant and fearless Dean Van Lines driver, one of the fastest men on dirt or pavement.

Eddie Sachs, a rookie making his debut.

The Offenhauser engine remained universal — still producing roughly 330 horsepower from 270 cubic inches — but the true battleground had shifted to chassis geometry and weight distribution.

The “laydown” Epperly would prove the decisive innovation, its stability allowing higher sustained cornering speeds than any previous design.

Race Day