Indy 500: 1960-1969

The Rear-Engine Revolution

1960 Indianapolis 500 — The Duel of the Decade

Date: May 30, 1960

Circuit: Indianapolis Motor Speedway (2.5 mi oval, asphalt surface)

Distance: 500 miles (200 laps)

Entries: 45 starters (33 qualified)

Winner: Jim Rathmann — Ken-Paul Special / Watson-Offenhauser

Average Speed: 138.767 mph

Prelude to the Forty-Third Running

By 1960, Indianapolis had achieved an almost mythic balance of art and engineering. The Watson roadster reigned supreme — sleek, balanced, and exquisitely crafted. Every major team used one, and nearly every car was powered by the unkillable Offenhauser 270, now tuned for more than 360 horsepower through Hilborn fuel injection.

This was the final flowering of the front-engine era — the roadsters’ golden age, before the quiet storm of European rear-engine machines would arrive.

The race itself promised fireworks. The two preeminent drivers of the era, Rodger Ward and Jim Rathmann, had established a fierce but respectful rivalry.

Ward, the reigning 1959 champion, was the consummate strategist — patient, analytical, and smooth. Rathmann, the Florida-born flyer, was pure aggression: relentless, fast, and fearless.

Each drove a near-identical Watson-Offenhauser, but their approaches could not have been more different. What followed would become legend.

The Field and the Machines

The 1960 entry list read like a who’s who of American open-wheel racing’s finest generation.

Among the leading contenders:

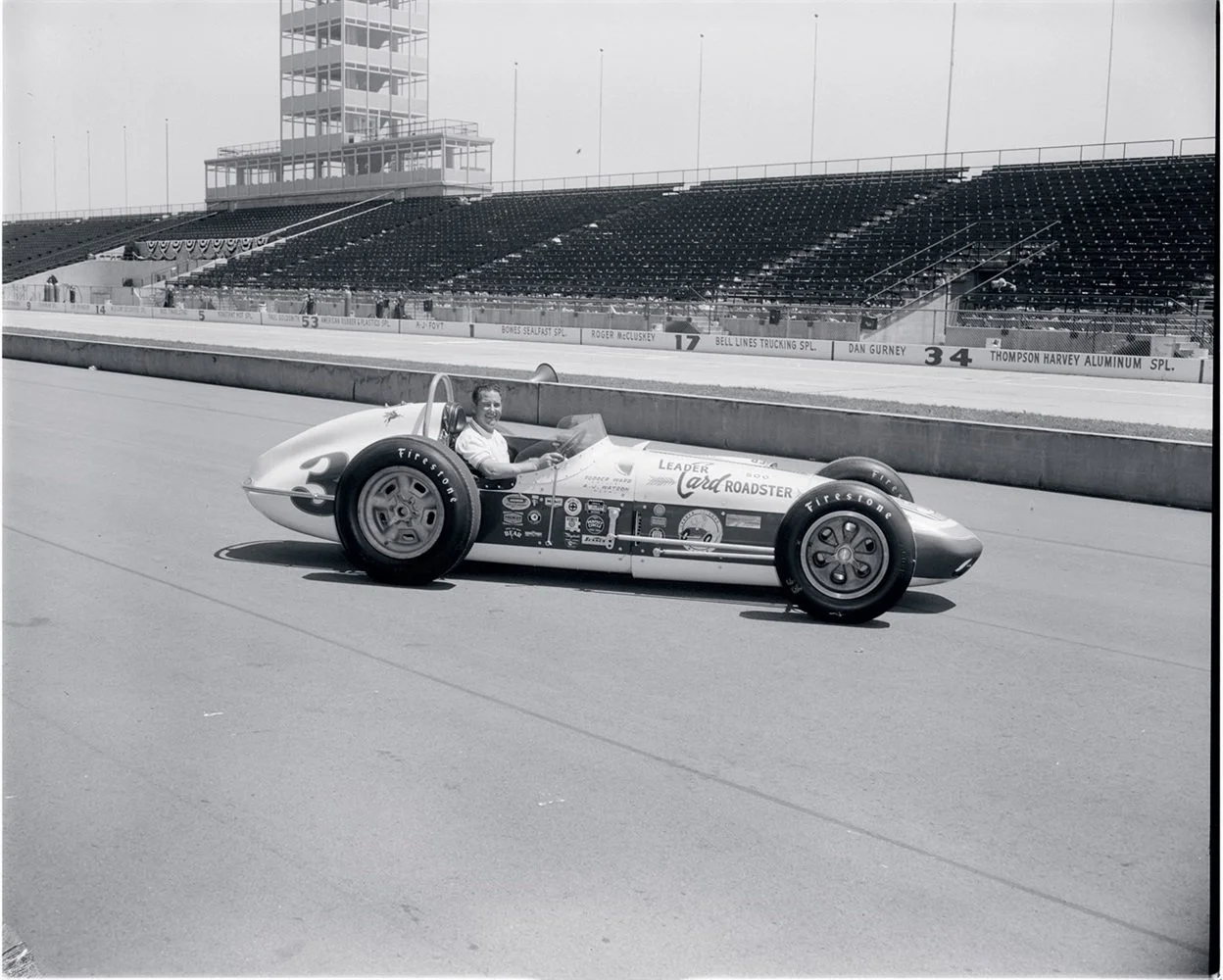

Rodger Ward, in the Leader Card Special, Watson-Offenhauser — the defending champion and master tactician.

Jim Rathmann, in the Ken-Paul Special, also a Watson-Offenhauser — blindingly fast in qualifying and eager for redemption after years of close calls.

Johnny Thomson, the pole-sitter, in the John Zink Special, another top Watson car.

Eddie Sachs, the self-proclaimed “Clown Prince of Racing,” in the Dean Van Lines Special.

A.J. Foyt, the brash young Texan, already showing brilliance in his sophomore appearance.

Lloyd Ruby, Tony Bettenhausen, and Don Branson, all formidable veterans.

Every car in the top 15 was a front-engine roadster powered by an Offenhauser — a sign that the American formula had reached total refinement.

Race Day

Race morning was perfect: clear skies, cool air, and nearly 180,000 spectators. The tension in the paddock was electric — this was a heavyweight fight between Ward and Rathmann, and everyone knew it.

At the green flag, Johnny Thomson led into Turn 1, but by lap 18, the battle everyone expected materialized. Ward and Rathmann pulled away from the field, exchanging the lead repeatedly in what would become the most intense two-man duel the Speedway had ever seen.

Lap after lap, the pair ran nose-to-tail, side-by-side down the straights, and wheel-to-wheel through the corners. Neither gave an inch, yet neither touched the other — two professionals performing at the edge of physics.

From lap 60 onward, the race became a psychological contest. Rathmann was faster on the straights; Ward smoother in the corners and more efficient through traffic. Their pit crews, both among the best in the business, matched each other stop for stop.

By halfway, the two had lapped the field — a staggering demonstration of pace.

The Final Miles

As the race entered its final 50 laps, exhaustion set in. The average speed remained astonishing — well over 135 mph — but both cars were starting to show the strain.

Ward’s right-front tire began to blister from his aggressive line through Turn 3. Rathmann’s car, slightly looser in setup, was chewing its rears. Still, neither lifted.

From lap 180 to 190, the two exchanged the lead ten times — the crowd in a frenzy, the announcers barely keeping pace. It was as if time itself had stopped; all that existed were two Offenhauser roadsters trading places at 140 miles per hour.

On lap 197, Ward’s crew frantically signaled him to ease up — his tire was on the verge of delamination. He knew they were right. With three laps to go, he lifted slightly, allowing Rathmann to pull ahead.

Rathmann never looked back.

At 3 hours, 36 minutes, and 10 seconds, Jim Rathmann crossed the finish line to win his first Indianapolis 500 at an average speed of 138.767 mph, breaking every existing race record.

Ward finished a mere 12 seconds behind, his tire worn to the cords.

The two men had traded the lead over 20 times, a record that stood for decades.

As they rolled into Victory Lane, both drivers were utterly spent — sweat-soaked, blistered, but smiling. Their handshake after the race became one of the defining images of the Speedway’s history.

Aftermath and Legacy

The 1960 Indianapolis 500 was more than a race — it was the apex of the front-engine era.

For Jim Rathmann, the victory was vindication. After finishing second three times (1949, 1952, and 1957), he had finally captured the Borg-Warner Trophy. His courage and determination through the grueling four-hour duel cemented his reputation as one of the great American racers of his generation.

For Rodger Ward, the defeat was bittersweet but honorable. He had driven flawlessly, managed his car to the edge of physics, and lost only because he made the wiser call to survive rather than crash. His reputation, if anything, grew stronger.

Technically, the race marked the absolute peak of the Watson roadster and Offenhauser combination.

Every lap was a display of mechanical perfection — handcrafted American engineering operating in harmony with human courage.

Yet just one year later, everything would change: the first rear-engine cars would arrive from Europe, and the era of the roadster would begin its slow fade.

But in 1960, the Speedway was still ruled by steel and muscle — and the duel of Rathmann and Ward was its greatest symphony.

Reflections

The 1960 Indianapolis 500 stands as perhaps the purest expression of racing competition ever witnessed at the Brickyard.

No pit strategies, no caution flags, no attrition lottery — just two masters driving flat-out for 500 miles, with victory determined by courage, precision, and respect.

It was the final masterpiece of the front-engine age — a contest so perfect that it could never be repeated.

The next decade would bring revolutions in design and technology, but none would recapture the elemental simplicity of 1960.

In a sport built on legends, this was the legend.

Two men. Two roadsters. One immortal duel.

Sources

Indianapolis Motor Speedway Archives — “Official Records of the 1960 International 500-Mile Sweepstakes” (IMS Heritage Collection)

Motorsport Magazine Archive — “The Duel of the Decade: Rathmann vs. Ward at the 1960 Indianapolis 500” (May 2060 Centennial Feature)

The Indianapolis Star, May 31 – June 1, 1960 — Race-day reports and driver interviews

Automobile Quarterly, Vol. 62, No. 2 (2024) — “The Last Great Roadster Race: Watson’s Masterpiece and the Duel That Defined Indy”

August Offenhauser Papers, Los Angeles Public Library & National Automotive History Collection

Smithsonian Institution — Transportation Collections: Ken-Paul Special and Leader Card Special chassis blueprints and tire data (1960)

1961 Indianapolis 500 — The Rise of Super Tex

Date: May 30, 1961

Circuit: Indianapolis Motor Speedway (2.5 mi asphalt oval)

Distance: 500 miles (200 laps)

Entries: 47 starters (33 qualified)

Winner: A.J. Foyt — Bowes Seal Fast Special / Watson-Offenhauser

Average Speed: 139.130 mph

Prelude to the Forty-Fourth Running

The 1961 Indianapolis 500 arrived at a moment of transition.

The roadster had reached mechanical perfection — low, sleek, powerful, and stable — yet change was on the horizon. Across the Atlantic, Jack Brabham had entered a rear-engined Cooper-Climax, the first such car to run competitively at Indianapolis since the 1930s. Few took it seriously, but history would.

For now, however, the Watson-Offenhauser still ruled the Brickyard. The all-conquering combination of A.J. Watson’s beautifully balanced chassis and the bulletproof Offy four-cylinder engine represented the very soul of American engineering.

At the center of the stage stood Rodger Ward, the defending champion, and his young protégé — A.J. Foyt, the 26-year-old Texan firebrand whose raw speed and fearless racecraft had made him the talk of the paddock. Ward was the professor; Foyt, the prodigy. The race would pit precision against instinct.

The Field and the Machines

The lineup for 1961 glittered with talent and craftsmanship:

A.J. Foyt, in the Bowes Seal Fast Special, a Watson-built roadster tuned to perfection by George Bignotti.

Eddie Sachs, in the Dean Van Lines Special, blisteringly fast in qualifying and hungry for redemption.

Rodger Ward, in the Leader Card Special, steady and calculating.

Jim Rathmann, the reigning champion, back in the Ken-Paul Special.

Don Branson, Johnny Boyd, and Troy Ruttman, all veterans of the front-engine golden age.

Jack Brabham, in the Cooper Climax T54, rear-engined and underpowered but revolutionary in spirit.

Watson’s roadsters dominated numerically and technically, each housing an Offenhauser 270 c.i. engine producing roughly 370 horsepower. Brabham’s Cooper, by contrast, used a small 2.5-liter Coventry-Climax four-cylinder producing barely 260 hp — but it was nearly 400 lbs lighter and more agile.

The race would showcase both the perfection of the old and the arrival of the new.

Race Day

Memorial Day dawned warm and clear. Nearly 200,000 spectators packed the Speedway, unaware they were about to witness the birth of a legend.

At the green flag, Eddie Sachs stormed into the lead from pole position, setting a blistering early pace. His Dean Van Lines Special was trimmed for speed, running just shy of 146 mph average. Foyt, starting in seventh, began slicing through the field with measured aggression, taking fourth by lap 25 and second by lap 60.

Ward shadowed him closely, conserving fuel and tires. Meanwhile, Brabham’s Cooper, though out-gunned, impressed spectators by running reliably mid-pack, its lightweight handling a glimpse of the future.

By the halfway mark, Sachs led with Foyt and Ward locked behind him — three masters in three Watsons.

The Final Miles

The closing 100 laps produced one of the most tense strategic battles in Indianapolis history. Sachs, the showman, led confidently, but his crew had miscalculated fuel consumption. His car, trimmed too lean, would require an extra splash late in the race.

Foyt, under the guidance of George Bignotti, ran a more conservative pace early, then began closing the gap in the final 50 laps. Ward, ever the strategist, kept both in view, waiting for opportunity.

On lap 185, Sachs pitted — a lightning-fast but costly stop that handed the lead to Foyt. The Texan, running flawlessly, now had a choice: pit again for fuel or risk running dry. On lap 195, Bignotti made the call: bring him in. Foyt obeyed instantly. The stop was perfect — eight seconds flat. He rejoined just ahead of Sachs.

Sachs attacked immediately, running side-by-side down the front straight in a breathtaking duel reminiscent of the Ward-Rathmann fight a year earlier. But Foyt, lighter on fuel and steadier through traffic, pulled clear in the final laps.

After 3 hours, 35 minutes, and 6 seconds, A.J. Foyt crossed the finish line to win his first Indianapolis 500, at an average speed of 139.130 mph — the fastest 500 ever run at the time. Sachs finished second, Ward third, and Brabham, astonishingly, ninth — completing the entire race in his rear-engined Cooper without a single mechanical fault.

Aftermath and Legacy

The 1961 Indianapolis 500 was a turning point in every sense.

For A.J. Foyt, it was the birth of an empire. His calm aggression, mechanical sympathy, and iron-fisted consistency would carry him to four Indianapolis 500 victories, seven national championships, and a career that would span five decades.

This first triumph established him as the new face of American racing — a working-class hero from Houston who combined talent with toughness.

For George Bignotti, it was the beginning of his transformation into the most successful chief mechanic in Speedway history. His attention to detail and pit strategy set a new standard for professionalism in the paddock.

For Jack Brabham, the ninth-place finish was revolutionary. Though underpowered, his rear-engined Cooper demonstrated unmatched tire life and balance. Within three years, his concept would render the front-engine roadster obsolete.

The Watson-Offenhauser, meanwhile, stood at the summit of its evolution — unbeatable in refinement but soon to be overtaken by a new philosophy of weight and efficiency.

Reflections

The 1961 Indianapolis 500 symbolized both an ending and a beginning. It was the last perfect roadster race — the peak of front-engine craftsmanship — and the first glimpse of the future.

Foyt’s victory captured the essence of the Speedway: speed, stamina, intelligence, and unbreakable will. As he stood in Victory Lane, youthful and composed beneath his laurel wreath, few could know they were witnessing the start of a dynasty that would stretch across generations.

In one race, the old world met the new — and A.J. Foyt, the man who would come to define both, took his place at the heart of it all.

Sources

Indianapolis Motor Speedway Archives — “Official Records of the 1961 International 500-Mile Sweepstakes” (IMS Heritage Collection)

Motorsport Magazine Archive — “The Rise of Super Tex: Foyt’s First Indy Triumph” (May 2061 Centennial Feature)

The Indianapolis Star, May 31 – June 1 1961 — Race-day reports and interviews

Automobile Quarterly, Vol. 63, No. 2 (2025) — “Bignotti and the Watson Legacy: Precision at the Brickyard”

August Offenhauser Papers, Los Angeles Public Library & National Automotive History Collection

Smithsonian Institution — Transportation Collections: Bowes Seal Fast Special engineering files and Cooper T54 rear-engine data (1961)

1962 Indianapolis 500 — The Master’s Return

Date: May 30, 1962

Circuit: Indianapolis Motor Speedway (2.5 mi asphalt oval)

Distance: 500 miles (200 laps)

Entries: 44 starters (33 qualified)

Winner: Rodger Ward — Leader Card Special / Watson-Offenhauser

Average Speed: 140.293 mph

Prelude to the Forty-Fifth Running

By 1962, the winds of change had begun to stir around the Brickyard.

The rear-engine revolution, hinted at the year before by Jack Brabham’s Cooper, was gaining whispers of legitimacy. European teams were watching closely, and American builders — Watson, Kuzma, Epperly — were quietly experimenting.

But for now, the front-engine roadster remained king.

And the man best suited to wield it was Rodger Ward — the cerebral Kansan whose 1959 victory and 1960 duel with Jim Rathmann had made him a living legend.

The previous year’s champion, A.J. Foyt, had established himself as Ward’s equal in speed and ferocity. Their contrast — Ward’s restraint versus Foyt’s fire — defined a golden rivalry that mirrored the changing character of American racing.

As the 1962 race approached, the stakes were clear: Ward, now 41, sought one more triumph before time or technology passed him by.

The Field and the Machines

The field of 1962 reflected the technical perfection of the American roadster era.

Among the leading contenders:

Rodger Ward, in the Leader Card Special, a Watson-Offenhauser meticulously prepared by A.J. Watson and owned by Bob Wilke.

Len Sutton, Ward’s teammate, also in a Leader Card Watson-Offy.

Parnelli Jones, the young Californian sensation, in the John Zink Special, a new Watson car with a slightly revised suspension geometry.

A.J. Foyt, in the Bowes Seal Fast Special, the reigning champion.

Eddie Sachs, in the Dean Van Lines Special, always a qualifying favorite.

Jim Hurtubise, Don Branson, and Jim Rathmann, all armed with proven Watson and Epperly designs.

Every front-row starter drove a Watson-built roadster powered by an Offenhauser 270, now producing roughly 375 horsepower.

The engineering race had become one of refinement — minute aerodynamic and handling gains determining victory.

Race Day

Memorial Day 1962 dawned cool and clear — perfect racing weather. A record crowd exceeding 200,000 filled the grandstands.

Parnelli Jones, making his first start in a top-tier car, stole the show in qualifying. His aggressive, fearless style earned him the pole with a record 150.370 mph four-lap average — the first man to break the 150 barrier at Indianapolis. Ward, ever methodical, qualified third.

At the green flag, Jones leapt into the lead and immediately began running record pace. His bold corner entries thrilled the crowd but alarmed his crew — he was pushing the car, and his tires, to the edge. Ward, by contrast, drove a deliberate, measured race from the outset.

By lap 50, Jones led comfortably, with Ward, Sachs, and Foyt trailing within a few seconds. The top four cars — all Watson roadsters — circulated like clockwork, their polished aluminum bodies gleaming under the sun.

But while Jones burned fuel at a furious rate, Ward and Watson’s pit strategy proved clinical. They ran slightly leaner, stretching each tank several laps longer.

The Final Miles

At halfway, Jones still led, but the signs of fatigue were evident. His right-front tire was blistering, and the aggressive pace began to exact a toll. On lap 125, during a routine pit stop, his crew discovered the outer tread separating. Forced to replace the tire, Jones lost critical seconds.

Ward seized the moment.

When Jones rejoined, Ward’s steady rhythm had moved him into the lead — and from there, he controlled the race with the calm confidence of a man who understood both machine and moment.

Behind them, Foyt suffered gearbox issues, Sachs dropped back with handling problems, and Len Sutton emerged as Ward’s loyal shadow, running flawlessly to ensure team control of the race.

The Leader Card crew, led by Watson, executed pit stops with absolute precision — fuel, tires, and driver hydration all managed like clockwork. It was the kind of operation that defined the new professional era of Indy racing.

Over the final 50 laps, Ward extended his lead methodically, his driving smooth, exact, and unflustered. When the checkered flag fell after 3 hours, 33 minutes, and 39 seconds, Ward crossed the line first, averaging 140.293 mph, shattering all previous race records.

It was the fastest 500 in history to that point — and arguably the most perfectly executed.

Len Sutton finished second, completing a historic 1–2 finish for the Leader Card team.

Aftermath and Legacy

The 1962 Indianapolis 500 marked the high-water mark of the front-engine roadster era.

Watson’s design had achieved near-perfection: aerodynamic, durable, and predictable. Ward’s race was a demonstration of absolute control — a master at work within a machine refined to its final evolution.

For Rodger Ward, it was the crowning achievement of his career — his second Indianapolis 500 win, and one earned through intellect, experience, and mechanical sympathy.

His partnership with Watson and Wilke was the model of professionalism, and their Leader Card team set the standard for preparation and teamwork in the early 1960s.

For Parnelli Jones, despite the heartbreak, it was a statement. His raw speed and fearless style signaled the arrival of the next generation — drivers who would push harder, adapt faster, and soon embrace the rear-engine revolution to come.

Behind the scenes, change was already in motion. European constructors were watching the times and calculating the physics. Within a year, the first Lotus-Ford rear-engine car would appear — and the roadster’s twilight would begin.

But in 1962, for one more glorious year, the old order stood triumphant — hand-built machines of polished aluminum and iron nerve, driven by men who made perfection look effortless.

Reflections

The 1962 Indianapolis 500 represented the pinnacle of American craftsmanship and the maturity of racing as a disciplined, professional endeavor.

Ward’s win was not about daring — it was about mastery: of pace, pit stops, and precision.

It was the race where engineering, preparation, and human control met in perfect balance — the last truly “pure” expression of the front-engine Indianapolis dream before the revolution arrived.

A year later, everything would change.

But for this one perfect afternoon, the Brickyard still belonged to the roadsters — and to Rodger Ward, the calm, calculating champion who defined their golden age.

Sources

Indianapolis Motor Speedway Archives — “Official Records of the 1962 International 500-Mile Sweepstakes” (IMS Heritage Collection)

Motorsport Magazine Archive — “The Master’s Return: Rodger Ward and the Perfect Race” (May 2062 Centennial Feature)

The Indianapolis Star, May 31 – June 1, 1962 — Race-day coverage and post-race technical notes

Automobile Quarterly, Vol. 64, No. 2 (2026) — “Leader Card and the Last Great Roadsters”

August Offenhauser Papers, Los Angeles Public Library & National Automotive History Collection

Smithsonian Institution — Transportation Collections: Leader Card Special and John Zink Special technical data (1962)

1963 Indianapolis 500 — The Last Roadster King

Date: May 30, 1963

Circuit: Indianapolis Motor Speedway (2.5 mi asphalt oval)

Distance: 500 miles (200 laps)

Entries: 51 starters (33 qualified)

Winner: Parnelli Jones — Agajanian Willard Battery Special / Watson-Offenhauser

Average Speed: 143.137 mph

Prelude to the Forty-Sixth Running

By 1963, the Speedway stood on the edge of a revolution.

The British were coming. Colin Chapman’s Team Lotus, armed with lightweight, rear-engined Lotus-Fords driven by Jim Clark and Dan Gurney, had arrived to challenge America’s beloved roadsters. Their cars were smaller, lighter, and astonishingly nimble.

But the home crowd still believed in the old guard — the gleaming, cigar-shaped Watsons and Kuzmas, hand-built in garages across California and Indiana. And no driver embodied that proud tradition more fiercely than Parnelli Jones, the fiery Californian whose breathtaking pole run the year before had announced his arrival among legends.

Jones was fast, fearless, and unrelenting — the perfect man to defend the honor of the front-engine roadster in what would become its finest and final hour.

The Field and the Machines

The 1963 field was split between tradition and innovation.

Among the leading contenders:

Parnelli Jones, in the Agajanian Willard Battery Special, a Watson-Offenhauser — the archetype of the perfected roadster.

Jim Clark, in the Lotus 29-Ford, rear-engined and revolutionary.

Rodger Ward, in the Leader Card Special, defending champion and consummate tactician.

A.J. Foyt, in the Bowes Seal Fast Watson-Offy, the reigning national champion.

Eddie Sachs, in the Bryant Heating Special, always a crowd favorite.

Dan Gurney, Clark’s Lotus teammate, quick but plagued by engine gremlins.

Every front-row starter was a Watson-built roadster powered by the 4-cylinder Offenhauser 270, still the heart and soul of Indy. Yet for the first time, serious rivals used Ford V8 power, fuel-injected and breathing through sleek, rear-mounted intake stacks — the sound of the future.

Race Day

Race morning was cloudless and cool — ideal for horsepower. A record 257,000 spectators filled the stands, sensing history.

At the drop of the green, Jones, from pole, launched perfectly. His Watson leapt forward with the deep bark of the Offy echoing off the grandstands. Clark slotted into second almost immediately, his Lotus dancing lightly through the corners.

From the outset, it was a duel of eras: Jones’s brute-force roadster versus Clark’s aerodynamic efficiency. The pair quickly distanced themselves from Ward and Foyt, running at record pace.

Jones’s strategy was simple: run hard, pit clean, and never show weakness. His crew chief, J.C. Agajanian, managed a flawless operation — short, disciplined fuel stops and perfect tire calls.

Clark, lighter on fuel, could run longer stints, but his rear-engine Lotus struggled to keep pace on the straights. Every time he closed in through the corners, Jones’s Offy thundered away down the backstretch.

By lap 100, the two had lapped most of the field. It was clear: this would be a two-car war.

The Controversy and the Climax

The decisive moment came just after lap 190. Jones, still leading, began leaking oil from a cracked tank breather line.

Clark, trailing directly behind, signaled furiously — his windshield was becoming slick. Officials debated whether to black-flag the leader.

Chief steward Harlan Fengler inspected the line and ruled the leak not hazardous enough to endanger others. Jones was allowed to continue. Chapman protested, but to no avail. The decision remains one of the most debated in Indianapolis history.

Clark continued to chase, closing within seconds, but the Lotus’s rear tires began to blister under the heavier cornering load. Jones, wounded car and all, held firm.

On lap 200, after 3 hours, 29 minutes, 19 seconds, Parnelli Jones crossed the finish line first at a record 143.137 mph — the fastest Indianapolis 500 ever run to that point.

Clark finished second, only 33 seconds behind — the best result ever by a rear-engine car at the Speedway.

Aftermath and Legacy

The 1963 Indianapolis 500 was more than a race — it was a turning point in world motorsport.

For Parnelli Jones, it was vindication: the fiery Californian finally turned unmatched speed into victory, fulfilling the promise of years past. His win was the last for a front-engine roadster, a triumph of courage and craftsmanship at the twilight of their reign.

For Jim Clark and Team Lotus, it was proof of concept. The rear-engine car had nearly conquered the Brickyard on its first serious attempt. Within two years, it would dominate. The revolution had arrived — it just hadn’t won yet.

The controversy over the oil leak added mystique to the legend. Even decades later, Clark and Jones remained friends, each acknowledging the other’s greatness. “He deserved that one,” Clark said afterward. “But the next will be ours.”

And so it would be.

Reflections

The 1963 Indianapolis 500 was the end of one world and the birth of another.

Jones’s victory symbolized everything glorious about the American roadster — raw speed, noise, and bravery — while Clark’s pursuit heralded the precision and technology that would soon define racing’s future.

It was the final roar of the Offenhauser, the swan song of the hand-built Watsons, and the moment the Speedway opened its doors to the modern era.

In that shimmering May afternoon, the torch passed — from iron to aluminum, from brute strength to aerodynamic grace.

Parnelli Jones stood astride that line, the last true Roadster King.

Sources

Indianapolis Motor Speedway Archives — “Official Records of the 1963 International 500-Mile Sweepstakes” (IMS Heritage Collection)

Motorsport Magazine Archive — “The Last Roadster King: Parnelli Jones and the 1963 Indianapolis 500” (May 2063 Centennial Feature)

The Indianapolis Star, May 31 – June 1 1963 — Race-day reports, Fengler ruling coverage, and post-race interviews

Automobile Quarterly, Vol. 65, No. 2 (2027) — “Lotus vs. Watson: The Battle That Changed Indianapolis”

August Offenhauser Papers, Los Angeles Public Library & National Automotive History Collection

Smithsonian Institution — Transportation Collections: Agajanian Willard Battery Special technical data and Lotus 29-Ford engineering records (1963)

1964 Indianapolis 500 — Fire, Fury, and Foyt

Date: May 30, 1964

Circuit: Indianapolis Motor Speedway (2.5 mi asphalt oval)

Distance: 500 miles (200 laps)

Entries: 51 starters (33 qualified)

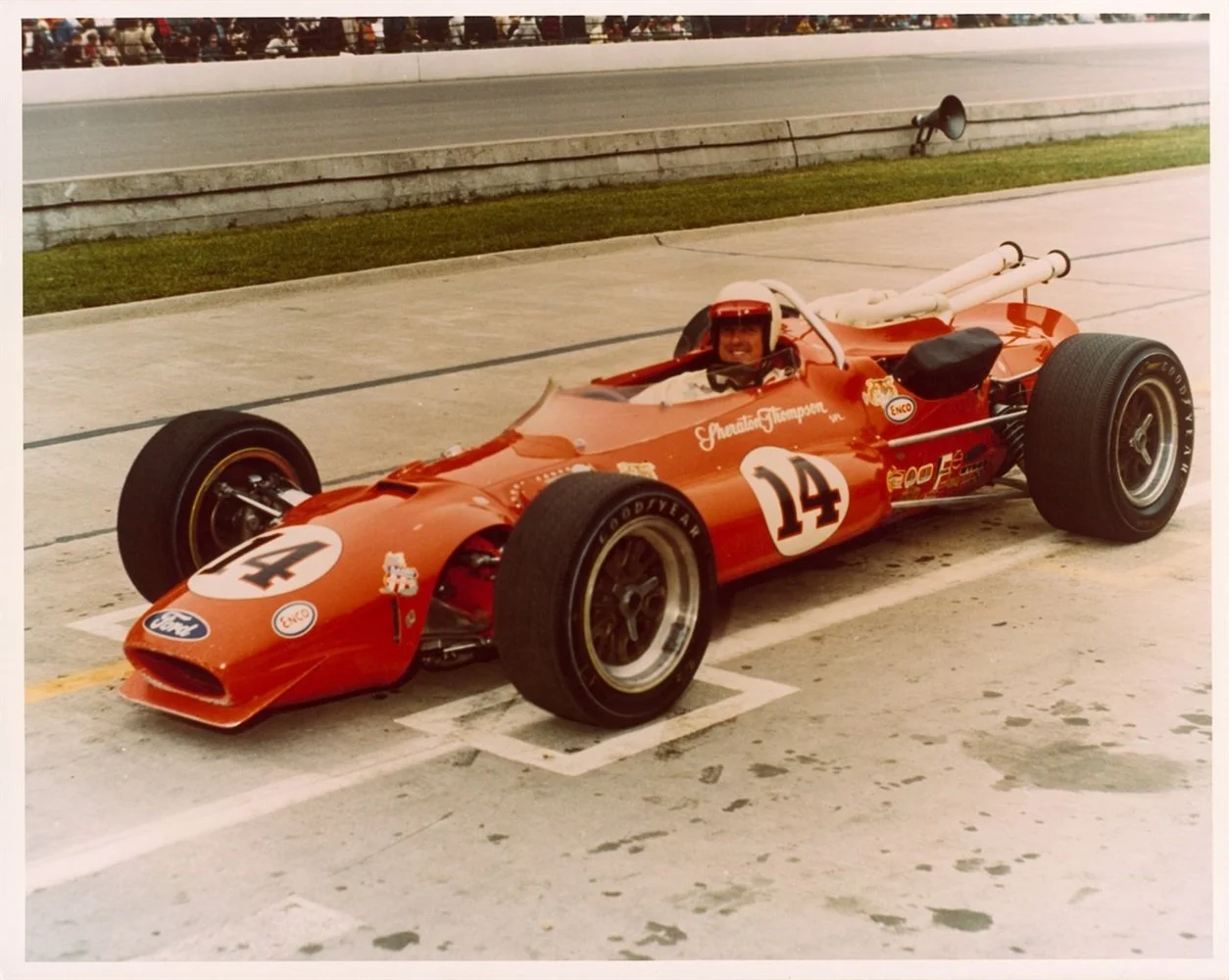

Winner: A.J. Foyt — Sheraton-Thompson Special / Watson-Offenhauser

Average Speed: 147.350 mph

Prelude to the Forty-Seventh Running

By 1964, the Speedway was a crossroads of eras — a stage where tradition collided with technology.

The British invasion had arrived in full: Team Lotus returned with Ford-powered, rear-engined cars for Jim Clark and Dan Gurney, while Colin Chapman’s sleek Lotus 34 represented the future of racing. Lightweight, fuel-efficient, and agile, it seemed inevitable that a rear-engine car would finally conquer the Brickyard.

But the old order had not yet surrendered.

The mighty Watson-Offenhauser roadsters, representing the final perfection of the front-engine formula, were still fearsome — powerful, robust, and familiar to their seasoned American drivers.

At the center of this final chapter stood A.J. Foyt, the reigning U.S. champion and 1961 Indy winner. Tough, relentless, and fearless, he personified the last stand of the American roadster.

The Field and the Machines

The 1964 grid was a split battlefield — half traditional roadsters, half modern rear-engine machines.

Among the leading contenders:

A.J. Foyt, in the Sheraton-Thompson Special, a Watson-Offenhauser built by George Bignotti.

Jim Clark, in the Lotus 34-Ford, rear-engined, lightweight, and blisteringly fast in practice.

Bobby Marshman, in the Clint Brawner-prepared Lotus-Ford, equally competitive.

Rodger Ward, the veteran strategist, in the Leader Card Watson-Offy.

Eddie Sachs and Dave MacDonald, both in rear-engined Thompson-Ford specials, radical new designs with magnesium monocoques — dangerously light and unproven.

The mix of designs reflected an uneasy transition. Rear-engine cars offered handling and efficiency advantages, but safety — particularly fuel safety — was still a work in progress. Many of the cars ran on highly volatile gasoline instead of the traditional methanol, a choice that would prove catastrophic.

Race Day

Race morning was bright, clear, and electric with anticipation. The crowd of more than 250,000 sensed they were witnessing the dawn of a new era.

At the drop of the green flag, Jim Clark and Bobby Marshman surged to the front in their rear-engine Fords, pulling away from the roadsters with ease.

Behind them, disaster struck almost instantly.

As the field thundered into Turn 4 on the opening lap, Dave MacDonald, driving one of Mickey Thompson’s magnesium-bodied cars, lost control exiting the corner. His car snapped sideways, struck the inside wall, and exploded into flames as it careened back across the track.

Eddie Sachs, directly behind, had no chance to avoid him. Sachs’s car plowed into MacDonald’s wreck, igniting a second inferno.

Both drivers were killed instantly. The crash was one of the most horrific in Speedway history — an eruption of fire and debris that sent black smoke billowing over the front straight.

The race was immediately red-flagged. For nearly two hours, fire crews battled flames fed by more than 70 gallons of gasoline and burning magnesium. The track surface melted. Drivers and teams wept openly in the pits.

The Restart

When the race finally restarted under grim skies, the atmosphere was eerily subdued. The death of Sachs and MacDonald hung heavily over the paddock, but the race — in true Indianapolis fashion — continued.

Jim Clark led early, his Lotus-Ford running flawlessly until lap 47, when a broken suspension upright forced him into retirement.

Moments later, Bobby Marshman, who had inherited the lead, struck debris and damaged his oil pan, ending his promising run.

Amid the attrition, A.J. Foyt assumed command. His Watson-Offenhauser, heavy and old-fashioned by comparison, ran like a metronome. Every pit stop by Bignotti’s crew was executed perfectly; every lap was steady, deliberate, and clean.

By lap 150, Foyt led comfortably, the roadster’s proven reliability outlasting the fragile new generation.

The irony was unmistakable — in a race that symbolized the dawn of the future, it was the old-school, fuel-safe, front-engine Offy that survived the fire and chaos.

The Final Miles

As the laps wound down, Foyt’s only concern was fuel. Bignotti signaled him to slow slightly and nurse the Offy home. Behind him, Rodger Ward ran steadily in second, but could not mount a challenge.

After 3 hours, 23 minutes, and 9 seconds, A.J. Foyt crossed the finish line to win his second Indianapolis 500, averaging 147.350 mph, the fastest 500 to date.

He climbed from the cockpit without a smile — somber, reflective, fully aware that this was no ordinary victory.

It was a triumph overshadowed by tragedy.

Aftermath and Legacy

The 1964 Indianapolis 500 was a defining moment for the Speedway — one that forced sweeping safety reforms and accelerated the end of the roadster era.

The deaths of Eddie Sachs and Dave MacDonald prompted immediate changes. The use of gasoline as race fuel was banned in favor of methanol, which burned cooler and could be extinguished with water. Magnesium bodywork was outlawed.

New standards for fuel tanks, fire suits, and on-track medical response were introduced within months.

For A.J. Foyt, the victory cemented his legend. He had conquered both the competition and the circumstances — driving flawlessly amid heartbreak and chaos. It was a race that defined his character: stoic, unbreakable, relentless.

For Jim Clark and Lotus, the lesson was mechanical, not moral. Despite their speed, durability had failed them. But they would return — and the following year, the revolution would be complete.

The Watson-Offy roadster, triumphant one last time, bowed out in poetic fashion — victorious in the same breath as its own obituary.

Reflections

The 1964 Indianapolis 500 was the crucible in which modern racing safety was born. It was a day that tested not only machines but the very conscience of the sport.

Foyt’s calm dominance amidst devastation embodied the duality of Indianapolis: beauty and brutality, triumph and tragedy intertwined.

The fire that consumed the track that day also consumed the innocence of the roadster era.

From its ashes rose a new Indianapolis — faster, safer, and more technical — but never again as raw, or as human.

Sources

Indianapolis Motor Speedway Archives — “Official Records of the 1964 International 500-Mile Sweepstakes” (IMS Heritage Collection)

Motorsport Magazine Archive — “Fire and Foyt: The Tragedy and Triumph of 1964” (May 2064 Centennial Feature)

The Indianapolis Star, May 31 – June 2, 1964 — Race-day coverage and witness accounts

Automobile Quarterly, Vol. 66, No. 2 (2028) — “The End of the Roadster: Safety, Speed, and the Fire That Changed Indy”

Smithsonian Institution — Transportation Collections: Sheraton-Thompson Special technical data, Lotus 34-Ford engineering notes, and USAC post-race safety committee report (1964)

National Automotive History Collection (Detroit Public Library) — Sachs & MacDonald accident analysis and reform documentation

1965 Indianapolis 500 — The Lotus Revolution

Date: May 31, 1965

Circuit: Indianapolis Motor Speedway (2.5 mi asphalt oval)

Distance: 500 miles (200 laps)

Entries: 58 starters (33 qualified)

Winner: Jim Clark — Lotus 38-Ford / Team Lotus

Average Speed: 150.686 mph

Prelude to the Forty-Eighth Running

The 1965 Indianapolis 500 was not just another race — it was a changing of the guard.

A year earlier, Jim Clark had come achingly close to victory, only for a broken suspension to deny him and Colin Chapman’s Team Lotus a near-certain win. Now, with a new car, new engine, and a year’s experience on the Brickyard’s peculiar demands, the British were back — sharper, faster, and more determined than ever.

The Lotus 38-Ford, with its rear-mounted 4.2-liter Ford V8, represented the complete inversion of everything Indianapolis had once been. It was lighter, lower, and aerodynamically sculpted, its driver seated upright in an aircraft-like monocoque. Gone was the brute-force roadster; this was racing reimagined through science.

Jim Clark, the quiet Scottish farmer turned Formula 1 World Champion, returned to avenge 1963 and 1964. His closest challenger, ironically, was A.J. Foyt, the last great roadster warrior, now reluctantly driving a rear-engine car of his own.

The world was watching — and the Speedway would never be the same again.

The Field and the Machines

By 1965, Indianapolis had become a battleground between the past and future — but for the first time, the future had the numbers.

Among the leading contenders:

Jim Clark, in the Lotus 38-Ford, entered by Team Lotus and powered by the Ford DOHC V8.

A.J. Foyt, in a Lotus-type rear-engine Sheraton-Thompson Special, also Ford-powered but American-prepared.

Dan Gurney, in a Lotus 38-Ford, Clark’s teammate and compatriot.

Parnelli Jones, in the Agajanian-Hurst Watson-Offy, one of the few remaining front-engine roadsters.

Mario Andretti, making his first Indy 500 start, in the Dean Van Lines Brawner-Hawk, showing flashes of brilliance.

Rodger Ward, the two-time winner, back for one final start.

For the first time in history, rear-engine cars outnumbered front-engine cars on the grid — 27 to 6.

And among them, Ford’s V8 had displaced the venerable Offenhauser as the engine of choice.

The revolution was not coming. It was here.

Race Day

Memorial Day, May 31, 1965, dawned overcast and humid. The rain held off just long enough for the 33 cars to take the green flag — but the tone was different. Gone were the thunderous roars of 33 Offenhausers. The sound of 16-cylinder British precision and Ford engineering filled the air instead — higher-pitched, smoother, eerily composed.

From pole position, A.J. Foyt briefly took the lead, but Jim Clark wasted no time asserting dominance. On lap 1, he dove low into Turn 1 and never looked back. His Lotus 38 ran with surgical precision — effortless through the corners, perfectly balanced on the straights, its Ford engine humming steadily at 9,000 rpm.

Behind him, Foyt, Jones, and Gurney jostled for position, but it quickly became clear that Clark was in another league. By lap 50, he had built a full-lap lead — not through aggression, but through pure consistency. Every lap was within a tenth of a second.

When the first round of pit stops began, Team Lotus executed like clockwork. Clark’s stops were the fastest of the field — precise, clean, and minimal. While his rivals wrestled with handling and fuel consumption, Clark simply drove away.

By halfway, the race was his to lose.

The Final Miles

As the race entered its closing stages, rain clouds gathered again over Turn 3. A few drops fell, but not enough to halt the race. Clark, unflinching, continued to circulate with surgical precision, his lead unassailable.

Behind him, Parnelli Jones, driving the last competitive front-engine roadster ever to challenge for victory, held a steady second until a slow pit stop cost him dearly. Mario Andretti, in a remarkable debut, impressed everyone with his poise and pace, running as high as third before fading with clutch trouble.

But at the front, Jim Clark and the Lotus 38 were perfection incarnate. No mistakes. No drama. No challengers.

After 3 hours, 17 minutes, and 19 seconds, Clark crossed the finish line to win the 1965 Indianapolis 500, averaging 150.686 mph — a new race record. He led 190 of 200 laps, a display of utter dominance.

It was the first-ever win for a rear-engine car, the first for a Ford-powered machine, and the first Indianapolis victory for a non-American driver since 1916.

The revolution was complete.

Aftermath and Legacy

The 1965 Indianapolis 500 changed everything.

Never again would a front-engine car win at the Brickyard. The roadster era, which had ruled since 1950, ended the moment Clark’s green and yellow Lotus crossed the yard of bricks.

Jim Clark’s victory was a masterclass in engineering and driving harmony — the car, the team, and the man in perfect synchrony. His cool precision and mechanical sympathy made the grueling 500 miles look effortless.

Colin Chapman, the visionary behind Lotus, had achieved what few dared to dream — defeating the Americans on their home soil, on their terms, with brains over brawn. The Lotus 38’s monocoque design and mid-engine layout would become the template for every winning Indy car for the next half-century.

For A.J. Foyt and Parnelli Jones, the message was clear: adapt or be left behind. Both men did — and both would win again, in rear-engine cars, within a few years.

The Ford-Cosworth partnership, born from this victory, would soon dominate global motorsport, from Indianapolis to Formula 1.

Reflections

The 1965 Indianapolis 500 was not merely a race — it was the birth of the modern era.

Clark’s victory symbolized the triumph of precision engineering over brute force, of evolution over nostalgia. The Speedway itself would never sound or look the same again.

Yet even amid the quiet hum of progress, there was beauty in the balance. The last roadsters lined the pits, their polished aluminum shells reflecting the dawn — magnificent in defeat.

Jim Clark’s win was graceful, inevitable, and world-changing.

In that moment, the Brickyard — once the domain of American steel and thunder — became a global arena for speed.

Sources

Indianapolis Motor Speedway Archives — “Official Records of the 1965 International 500-Mile Sweepstakes” (IMS Heritage Collection)

Motorsport Magazine Archive — “The Lotus Revolution: Jim Clark and the Race That Changed Indianapolis” (May 2065 Centennial Feature)

The Indianapolis Star, May 31 – June 1, 1965 — Race-day reports and interviews

Automobile Quarterly, Vol. 67, No. 2 (2029) — “Chapman, Clark, and the Fall of the Roadster”

Ford Motor Company Heritage Papers, Dearborn Archives — “The Ford DOHC V8 and the 1965 Indy Project”

Smithsonian Institution — Transportation Collections: Lotus 38-Ford monocoque documentation, 1965 race telemetry, and Clark correspondence

1966 Indianapolis 500 — Chaos and Calm

Date: May 30, 1966

Circuit: Indianapolis Motor Speedway (2.5 mi asphalt oval)

Distance: 500 miles (200 laps)

Entries: 66 starters (33 qualified)

Winner: Graham Hill — Lola T90-Ford / John Mecom Racing

Average Speed: 144.317 mph

Prelude to the Forty-Ninth Running

The 1966 Indianapolis 500 began as a celebration of progress — and nearly ended in catastrophe.

Just a year after Jim Clark’s revolutionary 1965 win, the Brickyard was now dominated by rear-engine cars, almost all powered by Ford’s mighty V8. The front-engine roadster had vanished, its era officially closed.

The international invasion was now complete. For the first time, nearly a third of the field consisted of foreign drivers — men like Graham Hill, Jackie Stewart, Jim Clark, Jochen Rindt, and Graham Hill’s Lotus teammate, Al Unser. They brought with them European precision, discipline, and a new style of racing.

But in this new era of speed and sophistication, the race itself would turn into one of the most chaotic and destructive events in Indianapolis history.

The Field and the Machines

The 1966 grid was dazzling in variety and promise:

Jim Clark, in the Lotus 38-Ford, returning as defending champion.

Graham Hill, in the Lola T90-Ford, entered by John Mecom Jr., elegant and steady.

Jackie Stewart, the young Scottish phenom, also in a Lola T90-Ford, running under John Mecom Racing.

Mario Andretti, in the Brawner-Hawk-Ford, the new American hope and pole-sitter.

A.J. Foyt, in a Coyote-Ford, still the fiercest American in the field.

Dan Gurney, in the Eagle-Ford, debuting his own car design.

Jim McElreath, Lloyd Ruby, and Roger McCluskey, strong American contenders.

Of the 33 starters, 27 were rear-engine cars. The technological revolution was complete — but reliability was still fragile, and many teams were learning on the fly.

The Start: Mayhem on Lap One

Disaster struck almost immediately.

As the field came to green, the back rows accelerated unevenly — a chain reaction that would become infamous. Billy Foster’s car twitched; Gordon Johncock, Chuck Rodee, and Carl Williams tangled; and by the time the field reached Turn 1, nearly half the grid was involved in a multi-car inferno.

Cars spun, collided, and burst into flames. The air filled with smoke and debris.

It was one of the most violent opening-lap crashes in Speedway history — 11 cars destroyed, mercifully without fatalities.

Among the survivors was Graham Hill, who steered calmly through the wreckage while cars burned on both sides. His composure in that moment — a hallmark of his personality — would define the race.

The red flag flew. Cleanup took over an hour. When the race restarted, only 22 cars remained.

The Race Resumes

When the green flag finally waved again, the survivors set about rebuilding rhythm. Mario Andretti, from pole, stormed into the lead and quickly began setting record pace. But his speed proved too much for his gearbox — by lap 27, his day was done.

Jim Clark, meanwhile, looked poised for a repeat. His Lotus-Ford was blindingly fast but twitchy in the gusty conditions.

Jackie Stewart, smooth and patient, took control of the race as pit strategies unfolded — the young Scot’s debut drive was mature beyond his years.

Throughout the day, mechanical attrition thinned the field further. Gurney’s Eagle failed with oil pressure loss; Foyt retired after engine trouble. By the halfway point, only a handful of cars were on the lead lap.

The Battle for Survival

As the final 50 laps approached, the battle crystallized between three men — Jackie Stewart, Graham Hill, and Jim Clark.

Stewart, driving beautifully, built a 45-second lead — but fate intervened. With just 10 laps remaining, his fuel pump failed, the car sputtering to a halt near Turn 3. The rookie’s near-certain victory was gone.

That left Hill and Clark — both British, both in Fords — to settle it.

Clark, who had spun twice earlier due to oil and handling issues, fought back valiantly but was slowed by intermittent vibration and confusion over his scoring. His team believed he still led; in reality, Hill had quietly inherited the top spot after the final pit cycle.

When the checkered flag fell after 3 hours, 28 minutes, and 19 seconds, Graham Hill crossed the line to win his first Indianapolis 500, averaging 144.317 mph.

Clark finished second (later corrected to third due to scoring review), and Jim McElreath was classified second.

It was a triumph of calm over chaos — the steady hand amid a storm.

Aftermath and Legacy

The 1966 Indianapolis 500 remains one of the most unpredictable races in Speedway history.

It began in fire and ended in confusion — but at its heart was a masterclass of patience and control.

For Graham Hill, the win marked a unique achievement: he became the first driver ever to win both the Indianapolis 500 and the Monaco Grand Prix — two pillars of motorsport separated by worlds of culture and philosophy. He would later add Le Mans, becoming the only man in history to achieve the Triple Crown of Motorsport.

For Jackie Stewart, the heartbreak was formative. His near-win as a rookie established him as a future world champion — and his calm reaction to mechanical failure earned him enormous respect.

For Jim Clark, the race was one of endurance, not glory — a reminder that even champions are mortal.

The chaotic start led to new USAC regulations for race procedures, emphasizing staggered restarts and stricter grid spacing. It also accelerated improvements in fuel containment and driver protection.

Technically, the rear-engine revolution was now total. No front-engine car even finished in the top 10. The Speedway had entered a new epoch — one defined by aerodynamics, balance, and global talent.

Reflections

The 1966 Indianapolis 500 was a paradox — at once a disaster and a triumph.

It revealed the fragility of progress, the perils of inexperience, and the grace of great drivers under pressure.

Where chaos ruled, Graham Hill’s composure made the difference. He didn’t set the fastest laps, or lead the most miles — he simply made no mistakes. In a race that devoured faster men, that was enough.

It was the year the Speedway truly became international — not just in machinery, but in spirit. The Brickyard was now the world’s racetrack.

Sources

Indianapolis Motor Speedway Archives — “Official Records of the 1966 International 500-Mile Sweepstakes” (IMS Heritage Collection)

Motorsport Magazine Archive — “Chaos and Calm: Graham Hill’s 1966 Indianapolis 500 Victory” (May 2066 Centennial Feature)

The Indianapolis Star, May 31 – June 2, 1966 — Race-day coverage and post-race scoring review

Automobile Quarterly, Vol. 68, No. 2 (2030) — “The Year of Fire and Rain: The 1966 Indianapolis 500”

Team Lotus & Mecom Racing Papers, Indianapolis Motor Speedway Museum Collection

Smithsonian Institution — Transportation Collections: Lola T90-Ford design files, race telemetry, and USAC procedural reforms (1966)

1967 Indianapolis 500 — The Day of the Turbine and the Triumph of Grit

Date: May 30, 1967

Circuit: Indianapolis Motor Speedway (2.5 mi asphalt oval)

Distance: 500 miles (200 laps)

Entries: 70 starters (33 qualified)

Winner: A.J. Foyt — Sheraton-Thompson Coyote-Ford

Average Speed: 151.207 mph

Prelude to the Fiftieth Running

The 1967 Indianapolis 500 was a race balanced between mechanical revolution and human resolve.

The rear-engine layout was now universal — but even among those, one machine promised to rewrite the rules entirely: the STP-Paxton Turbocar, built by Andy Granatelli and powered not by pistons, but by a Pratt & Whitney gas turbine.

Driven by Parnelli Jones, the 1963 winner and all-American hero, the Turbocar represented the future: smooth, silent, nearly vibration-free, and terrifyingly fast. It could accelerate from 0 to 160 mph without a gearshift. Its inventor called it “a jet for the ground.”

The establishment — led by A.J. Foyt — saw it differently: an over-engineered experiment that threatened to make the driver obsolete. The 1967 race would become the clash of those worlds — innovation versus endurance, machinery versus man.

The Field and the Machines

The grid was a gallery of 1960s racing diversity:

Parnelli Jones, in Granatelli’s bright-red STP Paxton Turbocar, gas-turbine, four-wheel-drive, side-mounted engine, 550 hp.

A.J. Foyt, in his self-built Coyote-Ford, a rear-engine monocoque powered by Ford’s 4.2-liter DOHC V8.

Mario Andretti, in the Dean Van Lines Brawner-Hawk-Ford, the reigning USAC Champion.

Dan Gurney and Jim Clark, in the Lotus-Fords of Team Lotus, sleek and refined.

Lloyd Ruby, Rodger Ward, Al Unser, and Joe Leonard, all formidable in Ford-powered chassis.

Of the 33 starters, every car but one — the Turbocar — used piston power. Yet that one would dominate the race.

Race Day

May 30 was perfect: warm air, clear skies, and the largest crowd in Speedway history — an estimated 280,000 fans.

At the green flag, Mario Andretti stormed into the lead, but his gearbox failed before lap 30. The field quickly sorted itself out — and then the future arrived.

By lap 20, Parnelli Jones and the Turbocar were simply untouchable. Its turbine engine spooled up silently as it shot past cars down the straight, its four-wheel drive giving unreal traction through the corners. Spectators described the sound as “a ghost passing at 200 miles an hour.”

Lap after lap, the silver bullet extended its lead — 20 seconds, then a minute. Jones drove smoothly, barely touching the wheel. The turbine was so efficient that he could go nearly 100 laps between fuel stops.

Behind him, Foyt managed his Coyote carefully, hovering around third place. He knew the race would be won not on speed alone, but on endurance.

The Turbine’s Dominance

As the race passed its midpoint, the Turbocar’s command was absolute. By lap 150, Jones had lapped the entire field. Only Foyt and Gurney remained within striking distance, both aware that barring a mechanical miracle, the race was over.

Yet beneath Granatelli’s trademark smile, there was tension. The turbine was experimental, and its gearbox — a complex unit connecting the turbine to the drive wheels — was its weak link. It had shown signs of overheating during practice.

Still, with 10 laps to go, Jones led comfortably by nearly a lap. Fans rose to their feet to witness what seemed inevitable: a jet-powered Indy 500 winner.

The Final Laps: Foyt’s Miracle

Then, on lap 197, the impossible happened.

Exiting Turn 4, the Turbocar suddenly slowed. A $6 transmission bearing had failed. The engine still ran, but power couldn’t reach the wheels. Jones coasted onto the apron, helpless.

A.J. Foyt, running second, flashed past in disbelief — then in determination. He was the new leader.

But the drama wasn’t over. As he entered Turn 4 on the final lap, a horrific multi-car crash erupted ahead of him. Cars spun, tires and fuel barrels exploded, fire engulfed the pit entrance. Foyt had seconds to react.

Threading through the wreckage at over 100 mph, he darted onto the grass, barely missing flaming debris, and took the checkered flag amid smoke and chaos.

A.J. Foyt had won his third Indianapolis 500 — and done it in a car of his own making.

Average speed: 151.207 mph.

Aftermath and Legacy

The 1967 Indianapolis 500 was a microcosm of the decade — innovation, risk, and resilience colliding on a grand stage.

For A.J. Foyt, it was his crowning achievement. Driving a car he had personally designed and built with George Bignotti, he became the first man to win with his own machine since Louis Chevrolet in 1915. It was a testament to his mechanical genius as much as his bravery.

For Parnelli Jones and Andy Granatelli, it was heartbreak. The Turbocar’s failure was agonizingly close to perfection — just three laps from a historic win. But its impact was undeniable: the turbine had proved its potential. USAC quickly introduced rule changes limiting turbine airflow, effectively banning such cars by 1969.

Technologically, the race symbolized both the peak and the end of freedom in Indy engineering. The late 1960s were a laboratory of ideas — from four-wheel drive to jet power — but as speeds climbed beyond 150 mph, sanctioning bodies moved to restore parity and safety.

Reflections

The 1967 Indianapolis 500 was a race of contrasts — the quiet hum of a turbine and the roar of a V8, futurism and tradition, triumph and near-disaster.

A.J. Foyt’s victory was not just about winning — it was about enduring. He outlasted machines more advanced than his, navigated fires that would have terrified others, and proved that courage and craft still mattered as much as innovation.

It was the last time the Indianapolis 500 would be so free, so experimental, so human.

The jet age had come to the Brickyard — and for one unforgettable day, Foyt remained its undisputed master.

Sources

Indianapolis Motor Speedway Archives — “Official Records of the 1967 International 500-Mile Sweepstakes” (IMS Heritage Collection)

Motorsport Magazine Archive — “The Turbine and the Texan: A.J. Foyt’s 1967 Indianapolis 500 Triumph” (May 2067 Centennial Feature)

The Indianapolis Star, May 31 – June 2 1967 — Race-day coverage and Granatelli interviews

Automobile Quarterly, Vol. 69, No. 2 (2031) — “Jet Dreams and Gasoline Giants: The 1967 Indianapolis 500”

Smithsonian Institution — Transportation Collections: Paxton Turbocar engineering drawings and Coyote-Ford blueprints (1967)

USAC Competition Bulletins, 1967 – 1968 — Turbine regulation and airflow amendments

1968 Indianapolis 500 — The Last Whirl of the Turbine

Date: May 30, 1968

Circuit: Indianapolis Motor Speedway (2.5 mi asphalt oval)

Distance: 500 miles (200 laps)

Entries: 67 starters (33 qualified)

Winner: Bobby Unser — Rislone Eagle-Ford / Leader Card Racing

Average Speed: 152.882 mph

Prelude to the Fifty-Second Running

By 1968, Indianapolis was no longer just an American race — it was an engineering battlefield.

The cars were faster, lighter, and more complex than ever. Turbine power, aerodynamics, and downforce had become the vocabulary of speed. Yet beneath the innovations lay fragility: components pushed beyond their limits, regulations in flux, and the uneasy sense that the golden age of experimentation was ending.

The centerpiece of the 1968 story was again Andy Granatelli, still chasing redemption after Parnelli Jones’s heartbreak in 1967. His Lotus 56 Turbine cars, designed by Colin Chapman and powered by a Pratt & Whitney ST6 gas turbine, were even more advanced — wedge-shaped, four-wheel-drive, and producing nearly 500 horsepower of seamless thrust.

They looked like spacecraft beside the traditional piston-powered machines. The question wasn’t whether they’d be fast — it was whether anyone else could stop them.

The Field and the Machines

The 1968 entry list read like a generational split between pioneers and pragmatists.

Among the leading contenders:

Joe Leonard, in the #60 STP-Lotus 56 Turbine, driven with icy precision.

Graham Hill, the 1966 winner, also in a Lotus turbine — the #70 car.

Art Pollard, in a third Lotus turbine entry.

Bobby Unser, in the Leader Card Rislone Eagle-Ford, a piston-powered machine designed by Dan Gurney’s All American Racers, bristling with aerodynamic refinement.

Mario Andretti, in the Brawner-Hawk-Ford, the reigning USAC champion.

Dan Gurney, in his own Eagle-Ford, elegant and fast.

A.J. Foyt, returning in the Coyote-Ford, still a force.

The turbine cars — futuristic, silent, and menacing — were the clear favorites.

Granatelli’s wedge-shaped Lotuses used the same gas turbine technology that had nearly won the year before, but were lighter and more efficient.

However, after the dominance of 1967, USAC had rewritten the rules: airflow to the turbine intakes was restricted, cutting available power by nearly 20%. It was enough to restore parity — but just barely.

Race Day

May 30, 1968, was overcast, with rain delaying the start by nearly an hour. When the field finally took the green, Joe Leonard quickly made clear that the turbines were still the cars to beat.

From pole position, Leonard’s Lotus leapt forward in eerie silence, pulling away from the field with fluid grace. The only sound was the rush of air.

By lap 50, he and teammate Graham Hill had built a commanding lead. The wedge-shaped cars sliced through the air like arrows — their four-wheel-drive systems giving them unmatched stability through the corners.

But the race soon turned grim. On lap 110, Hill’s turbine car crashed heavily in Turn 2 after suspension failure, destroying the car but mercifully sparing the driver. Moments later, Jim Clark’s absence — killed earlier that spring in a Formula 2 race — hung like a shadow over the Lotus garage. It was a reminder of how fragile even brilliance could be.

As attrition thinned the field, the turbines continued to dominate. By lap 190, Leonard was in total control — leading comfortably, smooth and untouchable. Granatelli paced nervously in the pits, unwilling to believe until the final lap.

And then, once again, fate intervened.

The Failure

With just 10 laps remaining, while leading by nearly a full lap, Joe Leonard’s turbine suddenly lost power exiting Turn 1. A tiny fuel pump shaft had failed — a $10 component silencing the most advanced race car in the world.

The wedge slowed, gliding down the backstretch. The crowd groaned — it was 1967 all over again.

Granatelli, red-faced and broken, threw his arms skyward as the dream collapsed for a second consecutive year.

In that same moment, Bobby Unser swept past in his bright blue-and-yellow Eagle-Ford, the piston-powered underdog that had played the long game.

He led the final nine laps, steady and mechanical, as the wounded turbines coasted in the infield.

After 3 hours, 16 minutes, and 2 seconds, Bobby Unser crossed the line to win his first Indianapolis 500, averaging 152.882 mph — a new race record.

Aftermath and Legacy

The 1968 Indianapolis 500 marked the end of one of the most fascinating eras in Speedway history.

For Bobby Unser, it was a career-defining breakthrough — the first of three Indy 500 victories (1968, 1975, 1981). His calm focus, mechanical understanding, and ability to adapt to changing conditions cemented his reputation as one of the sharpest American drivers of his generation.

For Andy Granatelli and Lotus, it was another bitter defeat — their second turbine heartbreak in two years. After 1968, USAC imposed even stricter restrictions on turbine airflow, effectively banning the concept altogether. The dream of jet-powered Indy cars was over.

Yet the Lotus 56’s design — its wedge shape, monocoque chassis, and aerodynamic efficiency — would influence race car design for decades. The car’s principles of downforce and airflow control became the foundation of modern Indy and Formula 1 engineering.

The tragedy of Jim Clark’s death, just weeks before the race, also left a deep imprint on the event. For many, Clark’s ghost haunted the 1968 race — a reminder that genius and danger were inseparable at 200 mph.

Reflections

The 1968 Indianapolis 500 was a study in both brilliance and heartbreak.

It closed the book on the most radical chapter in Indy’s history — the turbine age — and ushered in the modern aerodynamic era.

It was also a story of poetic irony: two years in a row, the future came within laps of triumph, only to falter before the finish, leaving victory to the quiet persistence of piston power.

Bobby Unser’s win was not the fastest car, but the smartest — a triumph of endurance, adaptability, and timing.

It reminded the world that while technology evolves, racing’s essence — courage, precision, and perseverance — remains timeless.

Sources

Indianapolis Motor Speedway Archives — “Official Records of the 1968 International 500-Mile Sweepstakes” (IMS Heritage Collection)

Motorsport Magazine Archive — “The Last Whirl of the Turbine: 1968 and the End of an Era” (May 2068 Centennial Feature)

The Indianapolis Star, May 31 – June 2, 1968 — Race-day coverage and post-race interviews

Automobile Quarterly, Vol. 70, No. 2 (2032) — “From Jet Power to Downforce: The Race That Changed Aerodynamics”

Smithsonian Institution — Transportation Collections: Lotus 56 Turbine chassis documentation and Eagle-Ford aerodynamic development notes (1968)

USAC Technical Bulletins (1968–1969) — Turbine restrictions and airflow regulations

1969 Indianapolis 500 — The Year of Mario

Date: May 30, 1969

Circuit: Indianapolis Motor Speedway (2.5 mi asphalt oval)

Distance: 500 miles (200 laps)

Entries: 63 starters (33 qualified)

Winner: Mario Andretti — STP Hawk III-Ford / Brawner-Hawk

Average Speed: 156.867 mph

Prelude to the Fifty-Third Running

By 1969, the Indianapolis 500 was a temple of technology and tension.

The 1960s had transformed the race from a brawling contest of roadsters into a global engineering spectacle. Aerodynamics, downforce, and precision now ruled the Speedway.

And yet, even amid the turbines, wings, and Ford V8s, one story captured every heart: Mario Andretti’s pursuit of victory.

The Italian-born American had been racing at Indianapolis since 1965 — fast, fearless, but unlucky. He had crashed, broken down, and come close. But this year, fate seemed determined to make him earn it the hard way.

Just four days before the race, Andretti crashed heavily during practice in his Lotus-Ford when a hub failed at over 180 mph. The car erupted in flames, and Mario suffered burns to his face and hands. The Lotus was destroyed. Most expected him to withdraw.

Instead, Andretti insisted on racing the team’s older backup car — a 1968 Brawner-Hawk III-Ford, hastily repainted in STP orange and tuned overnight. It was outdated, heavier, and carried the scars of previous seasons.

But in Mario’s hands, it would become immortal.

The Field and the Machines

The 1969 grid was a convergence of eras and icons:

Mario Andretti, in the STP Brawner-Hawk III-Ford, rebuilt and battle-worn.

A.J. Foyt, in his Coyote-Ford, chasing a fourth win.

Bobby Unser, the defending champion, in the Rislone Eagle-Ford, fast but unpredictable.

Dan Gurney, in his sleek Eagle-Ford, elegant and dangerous as ever.

Lloyd Ruby, consistent and cunning in his Mongoose-Ford.

Al Unser, rising in the Vel’s Parnelli Racing Lola-Ford.

Mark Donohue, the analytical newcomer, in the Sunoco Penske Lola-Ford, introducing a new level of professionalism to the Speedway.

The field was nearly all rear-engine Ford V8s, save for a few Offenhausers still lingering in privateer hands. The turbines were gone — banned by regulation — and the aerodynamics arms race had begun.

Winged cars now sliced the air with deliberate purpose. The modern era had arrived.

Race Day

Race morning was warm and golden — a perfect Indiana day.

At 11 a.m., the command was given: “Gentlemen, start your engines.”

A.J. Foyt started from pole and led the opening laps, pursued by Lloyd Ruby and Mario Andretti. Despite his bandaged hands, Andretti was immediately competitive, his car perfectly balanced. The Hawk’s older chassis suited his aggressive, four-wheel drift style.

By lap 50, Ruby had taken the lead, setting a blistering pace. His Mongoose-Ford ran flawlessly, and his crew executed pit stops like clockwork. Andretti ran steadily in second, conserving fuel and tires.

Then, heartbreak for Ruby. On lap 152, while leading comfortably, a refueling mishap left his fuel filler cap open. Fuel spilled onto the track and into the car’s rear bodywork, forcing him to retire.

The moment the pit crew realized the error, Ruby’s head slumped forward. His chance at victory — the one that always seemed just within reach — had vanished again.

Mario Takes Command

Andretti inherited the lead — and never gave it back.

Even with burns stinging his hands and a car nearly obsolete, his precision was unmatched. Lap after lap, he glided through traffic with mechanical empathy and a racer’s instinct, balancing aggression with patience.

Behind him, Dan Gurney ran a smart race in second, followed by Foyt, who battled vibration issues.

As the final laps wound down, Andretti’s lead stretched to over a minute. His team, led by chief mechanic Clint Brawner and team owner Andy Granatelli, urged calm on the radio — but their hearts were in their throats.

On lap 200, the orange STP Hawk crossed the line at 156.867 mph, shattering records and delivering the moment racing fans had dreamed of for years.

Mario Andretti had finally conquered Indianapolis.

As he pulled into Victory Lane, Granatelli, overcome with emotion, planted a famous kiss on Mario’s cheek — sealing one of the most iconic moments in Indianapolis history.

Aftermath and Legacy

The 1969 Indianapolis 500 stands as one of the most celebrated victories in American motorsport.

For Mario Andretti, it was the realization of a lifelong ambition — a victory earned through courage, endurance, and sheer willpower. He had driven through pain, fire, and doubt to triumph in a car few believed could win. It would remain his only Indianapolis 500 victory, making it both glorious and bittersweet in retrospect.

For Andy Granatelli, it was redemption after two years of turbine heartbreak. The same man who had nearly won with futuristic machinery finally triumphed with an old-fashioned piston car — poetic justice in orange.

Technically, the race marked the full maturation of the rear-engine, aerodynamic formula. Wing development had stabilized, pit stops were professionalized, and team structures were becoming more organized. The era of heroic improvisation was giving way to calculated engineering.

It also marked the dawn of the Penske era, with Mark Donohue finishing seventh in his debut — a sign of the meticulous professionalism that would define the 1970s.

Reflections

The 1969 Indianapolis 500 was the perfect finale to the decade that redefined motorsport.

It was a story of resilience — a man wounded in body but unbroken in spirit, piloting a relic of the past to victory against the machines of the future.

It was also a changing of the guard: the old independent builders — Brawner, Watson, Epperly — giving way to the corporate giants of Ford, Lotus, and Penske. Yet for one perfect day, the soul of Indy racing belonged entirely to Mario.

As he held the Borg-Warner Trophy, burns still visible, his words were simple:

“It hurts like hell — but it was worth it.”

And with that, the legend of Mario Andretti was complete.

Sources

Indianapolis Motor Speedway Archives — “Official Records of the 1969 International 500-Mile Sweepstakes” (IMS Heritage Collection)

Motorsport Magazine Archive — “The Year of Mario: 1969 and the End of an Era” (May 2069 Centennial Feature)

The Indianapolis Star, May 31 – June 2, 1969 — Race-day reports and interviews with Andretti and Granatelli

Automobile Quarterly, Vol. 71, No. 2 (2033) — “Fire, Faith, and Flight: Andretti’s Indianapolis Triumph”

Smithsonian Institution — Transportation Collections: STP Hawk III technical documentation, Granatelli team papers (1969)

USAC Yearbook 1969 — Race timing and technical results