Indy 500: 1970-1989

The Turbo Era

1970 Indianapolis 500 — The Dawn of the New Order

Date: May 30, 1970

Circuit: Indianapolis Motor Speedway (2.5 mi asphalt oval)

Distance: 500 miles (200 laps)

Entries: 67 starters (33 qualified)

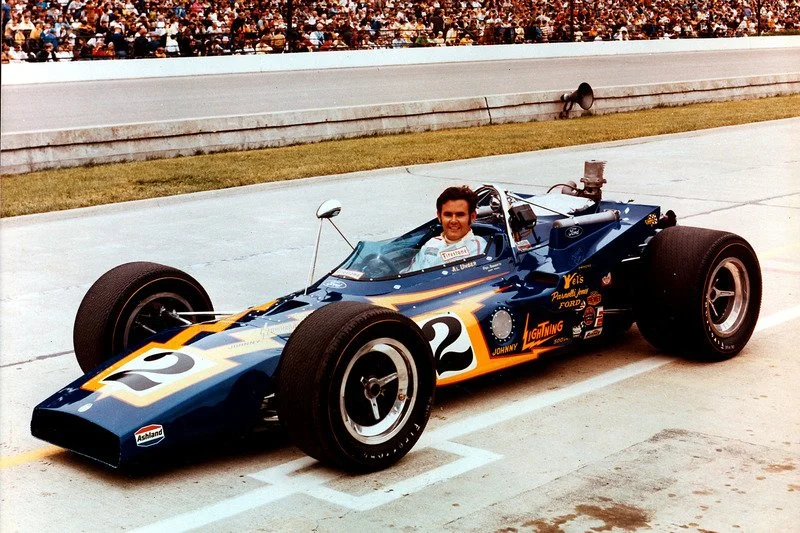

Winner: Al Unser — Johnny Lightning Special / Colt-Ford

Average Speed: 155.749 mph

Prelude to the Fifty-Fourth Running

The 1970 Indianapolis 500 marked a turning point — not only in engineering, but in attitude.

Gone were the turbine experiments, the raw, hand-built oddities of the 1960s. The new decade belonged to aerodynamic precision, sponsorship glamour, and factory-backed professionalism.

The U.S. Auto Club (USAC) had tightened rules, restricting innovation but boosting reliability and safety. Ford’s DOHC V8 still powered the majority of the grid, but focus had shifted from power to stability. Wing placement, airflow, and fuel strategy now separated contenders from the rest.

And into this refined landscape came Al Unser, younger brother of Bobby, driving for Vel’s Parnelli Jones Racing. The team, led by Parnelli Jones and Vel Miletich, was the perfect hybrid of old-school grit and modern discipline — the future of American racing management.

Unser had been fast before, but now he was ready to be great.

The Field and the Machines

The 1970 field featured one of the strongest grids in Indianapolis history — a blend of veterans, champions, and new-era precision machines.

Among the frontrunners:

Al Unser, in the Johnny Lightning Colt-Ford, a beautifully balanced, wedge-shaped car prepared by Parnelli Jones’s team.

A.J. Foyt, in the Sheraton-Thompson Coyote-Ford, still fiercely competitive.

Mario Andretti, the defending champion, in the STP Hawk III-Ford, fast but fragile.

Mark Donohue, leading Team Penske’s first serious assault on the 500, driving a Lola T150-Ford, representing the new corporate professionalism.

Lloyd Ruby, in the Mongoose-Ford, the eternal nearly-man.

Bobby Unser, in the Rislone Eagle-Ford, defending champion and older brother to Al.

Dan Gurney, in his Eagle-Ford, elegant as ever.

Aerodynamic wedges had replaced the rounded shapes of the 1960s. Every car now wore wings, radiators were reshaped for airflow, and pit work had become orchestrated science. The speedway looked and sounded modern.

Race Day

May 30, 1970, dawned warm, breezy, and brilliant — one of the finest race days in memory.

A record crowd of over 300,000 filled the Speedway as the cars rolled off the grid.

At the drop of the green, Al Unser, starting from pole position, surged into the lead immediately. The blue-and-yellow Johnny Lightning Special leapt off the line like a bullet, its wedge nose slicing through the air. Behind him, A.J. Foyt gave chase, while Ruby and Donohue settled into rhythm.

From the outset, Unser’s pace was mesmerizing. His driving style was fluid, almost effortless — never aggressive, never ragged. He ran within tenths of a second lap after lap, his pit stops perfectly timed by chief mechanic George Bignotti, whose methods had defined Indy racing strategy since the 1950s.

By lap 100, Unser had built a lead of more than a full lap over the field. His only competition, it seemed, was the clock.

The Middle Stints

Mechanical attrition soon claimed many big names.

Mario Andretti, the 1969 winner, retired early with a broken piston.

Dan Gurney dropped out with fuel issues.

Bobby Unser suffered gearbox trouble.

Mark Donohue, meticulous as ever, kept Team Penske’s first full Indy effort in contention, but his Lola couldn’t match the sheer pace of Unser’s Colt. Still, his consistency would earn a deserved seventh-place finish — an early glimpse of what was to come for Penske Racing.

Meanwhile, A.J. Foyt, running second, pushed hard to close the gap — but his Coyote’s suspension began to fail, forcing him to back off.

By lap 150, it was clear: unless disaster struck, the race belonged to Al Unser.

The Final Miles

The final 50 laps were a masterclass in discipline.

Bignotti and Parnelli Jones radioed calm instructions: conserve the car, hit every mark, take no risks.

Unser obeyed with mathematical precision. His Ford engine hummed steadily, the tires wore evenly, and every pit stop ran to the second.

As the checkered flag fell after 3 hours, 12 minutes, and 35 seconds, Al Unser crossed the line to win the 1970 Indianapolis 500, averaging 155.749 mph — one of the fastest races in Speedway history.

He led 190 of 200 laps, a display of dominance not seen since Jim Clark in 1965.

Behind him, Mark Donohue and Foyt were left to admire the clinical perfection of his run.

In Victory Lane, Unser’s expression was as composed as his drive. Holding the massive Borg-Warner Trophy beside his smiling brother Bobby, he said simply:

“We had a great car, and I never had to worry about a thing. That’s the best feeling in the world.”

Aftermath and Legacy

The 1970 Indianapolis 500 marked the beginning of the Unser dynasty and the maturation of the modern Indy 500 era.

For Al Unser, it was the first of four victories (1970, 1971, 1978, 1987) — a career that would make him one of the Speedway’s all-time greats. His calm precision, tire management, and consistency became the template for success in the new decade.

For Vel’s Parnelli Jones Racing, it was a triumph of professionalism and preparation. Their team organization, sponsorship polish, and engineering precision foreshadowed the structure of later juggernauts like Penske and Ganassi.

For the Speedway, the race represented the end of innocence. The days of home-built specials and freelance mechanics were gone. Corporate sponsorships — like Johnny Lightning — now painted the cars, and every element of the event was becoming part of the business of speed.

Technically, the race solidified the Colt chassis as the new standard — light, rigid, and perfectly suited to the Ford powerplant. The wedge aerodynamic concept proved decisive, and soon every major team adopted similar designs.

Reflections

The 1970 Indianapolis 500 was not a race of chaos or drama, but one of mastery.

It was the moment Indy evolved from a proving ground into a polished professional sport.

Al Unser’s performance was as clean and perfect as the decade ahead would strive to be — a balance of engineering, execution, and human serenity.

It was the antithesis of the fiery 1960s: no turmoil, no miracles, just quiet excellence.

The new era had arrived, painted in Johnny Lightning blue and gold, led by a man who never needed to shout to prove his greatness.

Sources

Indianapolis Motor Speedway Archives — “Official Records of the 1970 International 500-Mile Sweepstakes” (IMS Heritage Collection)

Motorsport Magazine Archive — “The Dawn of the New Order: Al Unser and the 1970 Indianapolis 500” (May 2070 Centennial Feature)

The Indianapolis Star, May 31 – June 2, 1970 — Race-day coverage and post-race interviews

Automobile Quarterly, Vol. 72, No. 2 (2034) — “Johnny Lightning and the Rise of the Professional Era”

Smithsonian Institution — Transportation Collections: Colt-Ford chassis data, Vel’s Parnelli team documentation (1970)

USAC Technical Yearbook 1970 — Race timing, chassis homologation, and aerodynamic regulations

1971 Indianapolis 500 — The Dynasty Takes Shape

Date: May 29, 1971

Circuit: Indianapolis Motor Speedway (2.5 mi asphalt oval)

Distance: 500 miles (200 laps)

Entries: 64 starters (33 qualified)

Winner: Al Unser — Johnny Lightning Special / Colt-Ford

Average Speed: 157.735 mph

Prelude to the Fifty-Fifth Running

The 1971 Indianapolis 500 arrived in a period of profound transition.

The 1960s had been about innovation and bravery; the early 1970s were about refinement and control.

The Speedway was now ruled by professional, corporate-backed teams — organized, strategic, and immaculate in execution.

The car that embodied this new professionalism was the Vel’s Parnelli Jones Racing Colt-Ford, sponsored by Johnny Lightning and tuned by chief mechanic George Bignotti.

It was not revolutionary — but it was perfected.

At its wheel was Al Unser, the reigning 1970 champion and the quiet assassin of the modern Indy age.

Where his brother Bobby was fiery and aggressive, Al was smooth, consistent, and impossibly calm. His strength was not flamboyance, but flawlessness.

Defending his title in 1971, Unser entered the race at the absolute height of his powers — in a car, and a team, that mirrored his own precision.

The Field and the Machines

The 1971 grid was one of quality and professionalism, dominated by wedge-shaped Colts, Eagles, and McLarens — each a product of wind-tunnel testing and aerodynamic study.

Among the leading contenders:

Al Unser, in the Johnny Lightning Colt-Ford, defending champion and race favorite.

Mark Donohue, leading Team Penske’s McLaren M16-Ford, making the team’s second full-scale assault on the Brickyard.

Peter Revson, also in a McLaren M16-Ford, the rising American star with F1 pedigree.

A.J. Foyt, in his Coyote-Ford, still ever-present and dangerous.

Mario Andretti, in an STP Hawk-Ford, trying to recapture his 1969 form.

Bobby Unser, in the Rislone Eagle-Ford, fast but plagued by mechanical inconsistency.

Jim Malloy, Lloyd Ruby, and Joe Leonard, all quick and capable.

The rear-engine revolution was long complete.

Every car was now a wedge-aero monocoque powered by the Ford DOHC turbocharged V8. With methanol fuel, wing adjustments, and a focus on consistency, these cars could now exceed 180 mph in race trim.

The era of polished, methodical dominance had arrived.

Race Day

May 29, 1971 — a Saturday running, as Memorial Day fell on a Sunday that year — dawned hot and humid under a pale Indiana sun.

A record crowd exceeding 300,000 filled the Speedway for what promised to be a clash between Unser’s precision and Penske’s preparation.

At the green flag, Peter Revson, starting from pole, led briefly into Turn 1, but Al Unser, starting second, surged past within two laps. His Colt-Ford was balanced, planted, and serene — every input smooth, every lap a metronome.

Behind him, Mark Donohue’s McLaren looked the only car capable of challenging, but Penske’s crew was still refining pit-stop coordination.

Through the opening 100 laps, Unser was untouchable. His blue-and-yellow Johnny Lightning car carved through traffic with mechanical grace, running consistent laps around 170 mph. He led nearly every circuit before halfway.

Pit stops were flawless — fuel, tires, tear-offs, and go.

George Bignotti’s crew had turned racing into choreography.

The Middle Stints

By lap 125, the rhythm of the race had settled.

Donohue ran second, his McLaren steady but slightly understeering in the heat.

Peter Revson fell back after a slow tire change, while A.J. Foyt maintained third until clutch problems forced him out.

Mario Andretti retired with turbo failure.

The fight narrowed to Unser versus Donohue — two drivers of discipline rather than drama, both representing the new corporate professionalism of American racing.

Donohue closed the gap to under 10 seconds after a rapid sequence of laps around 175 mph, but the Penske team’s conservative fueling strategy cost him momentum. When a late-race caution bunched the field, Unser immediately reasserted control, stretching the gap again once green.

The Final Miles

In the final 40 laps, Unser’s lead stabilized at more than a full lap.

He was unhurried, calculating, and mechanically gentle — an engineer’s dream driver. His Ford engine sang cleanly to the end, untouched by the mechanical failures that crippled others.

After 3 hours, 11 minutes, and 50 seconds, Al Unser crossed the line to win the 1971 Indianapolis 500, averaging 157.735 mph — a new record for a two-time winner.

He led 173 of 200 laps, nearly identical dominance to his 1970 performance.

Peter Revson finished second, giving McLaren its first Indy podium — the prelude to their coming dominance. Donohue placed third for Penske, marking the team’s first top-three finish at the Brickyard.

In Victory Lane, Unser was calm as ever, holding his second Borg-Warner Trophy beside his father Jerry and brother Bobby, who embraced him with tears of pride.

“It’s not about speed,” Al said simply. “It’s about doing everything right, every time.”

Aftermath and Legacy

The 1971 Indianapolis 500 marked the consolidation of the new era — discipline over daring, method over mayhem.

For Al Unser, it cemented his place among the all-time greats. Back-to-back victories placed him alongside legends like Wilbur Shaw, Mauri Rose, and Bill Vukovich. He had become the defining driver of the early 1970s — the face of professionalism in American open-wheel racing.

For Vel’s Parnelli Jones Racing, the repeat win validated their formula of structured teamwork and incremental refinement. The same chassis, the same engine, the same driver — the ultimate demonstration that in modern racing, consistency beats chaos.

For McLaren and Penske, the lessons of 1971 were invaluable. Both teams, already innovators in aerodynamics and engineering management, would apply what they learned to dominate the remainder of the decade.

Technically, the 1971 race marked the peak of the Ford era. The turbocharged V8, paired with Colt and McLaren chassis, reached its mechanical maturity. Within a few years, the Offenhauser turbo and new fuel systems would begin to challenge its supremacy.

Reflections

The 1971 Indianapolis 500 was not defined by drama, but by perfection.

It was the embodiment of what Indianapolis had become — a place where precision triumphed over passion, where engineers and strategists shaped destiny as much as drivers.

In an era of rising speeds and shrinking margins, Al Unser’s calm dominance reflected a simple truth: greatness at the Speedway is not measured in spectacle, but in control.

The fiery 1960s were over. The cool, calculated 1970s had arrived — and Al Unser was its undisputed king.

Sources

Indianapolis Motor Speedway Archives — “Official Records of the 1971 International 500-Mile Sweepstakes” (IMS Heritage Collection)

Motorsport Magazine Archive — “The Dynasty Takes Shape: Al Unser and the 1971 Indianapolis 500” (May 2071 Centennial Feature)

The Indianapolis Star, May 30 – June 1, 1971 — Race-day coverage and post-race commentary

Automobile Quarterly, Vol. 73, No. 2 (2035) — “Back-to-Back: The Perfection of Al Unser”

Smithsonian Institution — Transportation Collections: Colt-Ford chassis data and Vel’s Parnelli team strategy records (1971)

USAC Competition Yearbook 1971 — Race timing, pit strategy notes, and technical documentation

1972 Indianapolis 500 — The Science of Speed

Date: May 27, 1972

Circuit: Indianapolis Motor Speedway (2.5 mi asphalt oval)

Distance: 500 miles (200 laps)

Entries: 67 starters (33 qualified)

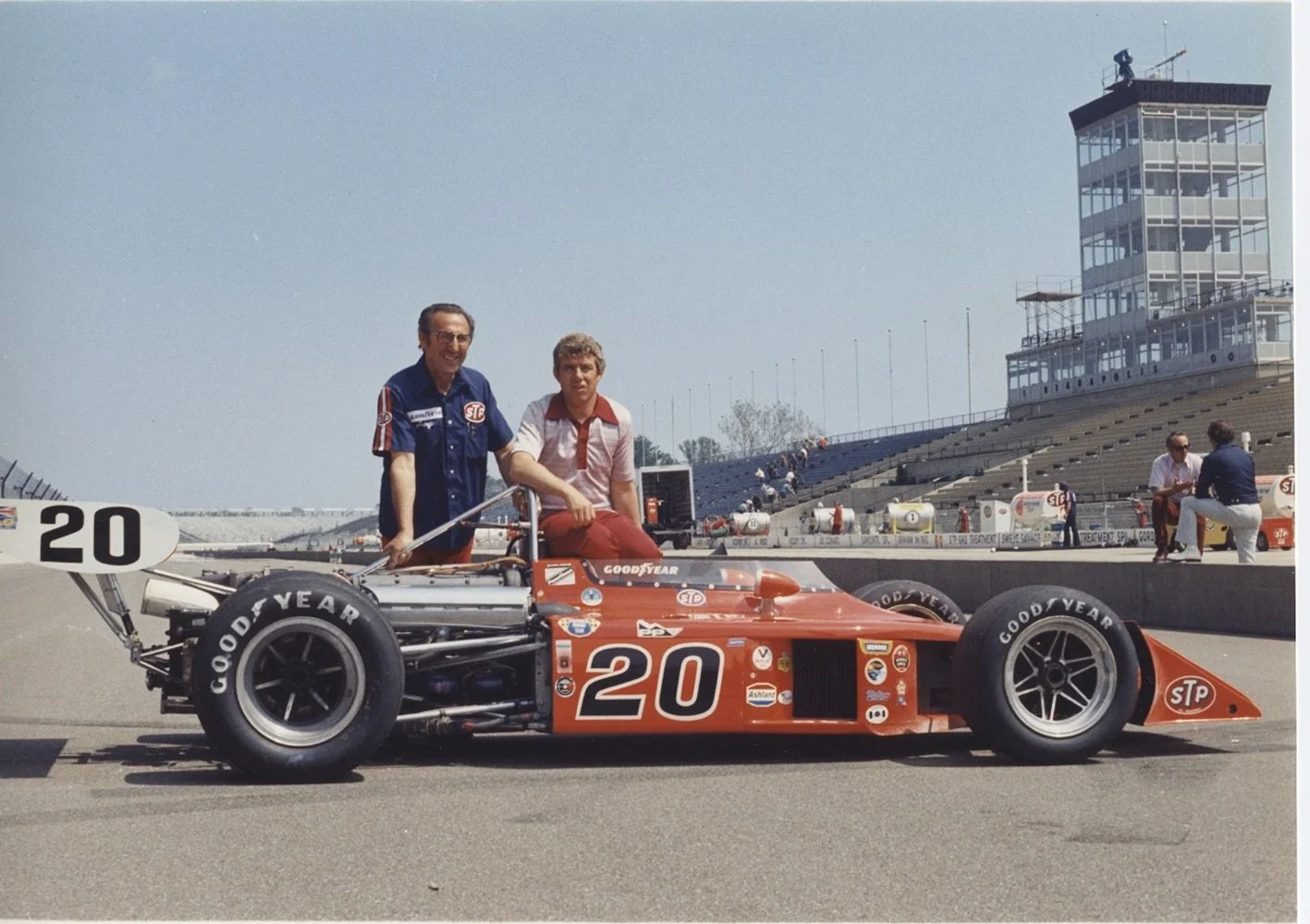

Winner: Mark Donohue — McLaren M16B-Ford / Team Penske

Average Speed: 162.962 mph (race record)

Prelude to the Fifty-Sixth Running

By 1972, the Indianapolis 500 had evolved into something unrecognizable from its roadster-era past.

Gone were the days of cigar-shaped cars, hand tools, and intuition. This was the era of data, wind tunnels, and corporate precision — and no team embodied that transformation better than Roger Penske’s Team Penske.

The young team had debuted only three years earlier, but its methodical approach — measured fuel strategies, military-level preparation, and analytical driver feedback — was reshaping the sport.

At the heart of that revolution was Mark Donohue, an engineer-driver unlike any before him.

Quiet, cerebral, and ruthlessly disciplined, Donohue approached racing like an equation. To him, speed was the product of systems — not chaos. The 1972 Indianapolis 500 would prove him right.

The Field and the Machines

The 1972 grid reflected the new age: sleek wedge shapes, gleaming sponsorships, and aerodynamic precision.

Among the leading contenders:

Mark Donohue, in the McLaren M16B-Ford, entered by Team Penske and sponsored by Sunoco.

Peter Revson, in a McLaren M16B-Ford, representing the factory McLaren team.

Bobby Unser, in the Eagle 72-Ford, blisteringly fast but unpredictable.

Al Unser, the two-time defending champion, in the Johnny Lightning Colt-Ford, now the benchmark for reliability.

A.J. Foyt, in the Coyote-Ford, ever-present and ever-dangerous.

Gary Bettenhausen, in the Olsenite Eagle-Ford, aggressive and determined.

Mike Mosley, Jerry Grant, and Johnny Rutherford, all competitive in Ford-powered chassis.

The new McLaren M16B, designed by Gordon Coppuck and refined by Penske’s engineers, was the car to beat. It featured a fully enclosed wedge design with integrated side pods, front and rear wings, and optimized aerodynamics that allowed for stable downforce at 190 mph.

Ford’s turbocharged DOHC V8 remained the dominant engine, producing roughly 800 horsepower on methanol.

Race Day

Saturday, May 27, 1972, was hot and dry — perfect conditions for a new speed era.

For the first time, official qualifying speeds surpassed 195 mph, with Bobby Unser capturing pole at a staggering 195.940 mph, breaking all previous records. The era of the 200-mph car was in sight.

At the start, Bobby Unser leapt into the lead, trailed by Peter Revson and Mark Donohue. The McLarens, with their superior aerodynamic balance, quickly began to assert dominance. By lap 30, the three orange-and-blue cars were controlling the pace.

But behind the scenes, Roger Penske’s precision was the difference. Every pit stop was rehearsed to perfection, every tire pressure logged to decimal accuracy. Donohue’s strategy was not to lead, but to control.

While Unser’s aggressive pace wore his tires, Donohue circulated consistently within two seconds of the leader, conserving fuel and components.

By lap 100, the plan began to unfold. Unser’s turbo overheated. Revson’s right rear tire blistered. And Donohue — calm, mathematical, unhurried — took the lead.

The Final Miles

The closing stages of the 1972 race were a masterclass in efficiency.

Donohue’s McLaren M16B glided around the Speedway with machine-like precision, its blue-and-yellow Sunoco livery flashing across the bricks in perfect rhythm.

Every variable — tire wear, fuel consumption, turbo temperature — was known, tracked, and managed.

The car never faltered. The driver never wavered.

As the final laps wound down, only Jerry Grant’s Eagle-Ford remained within distant sight. But Grant’s late-race pit confusion — mistakenly fueling in teammate Bobby Unser’s pit stall — handed the victory decisively to Donohue.

After 3 hours, 4 minutes, and 5 seconds, Mark Donohue crossed the line at an average speed of 162.962 mph, shattering the all-time race record by more than five miles per hour.

It was Team Penske’s first Indianapolis 500 victory — and the beginning of a dynasty that would come to define the next half-century of racing.

Aftermath and Legacy

The 1972 Indianapolis 500 was more than a race — it was a proof of concept.

For Mark Donohue, it was the crowning moment of a career defined by intellect and integrity. He became the first true "engineer-driver" to win the 500 — a man who could calculate, design, and execute victory with scientific precision. His post-race data notes ran longer than some teams’ race-day strategies.

For Roger Penske, it was the validation of his philosophy: preparation, precision, and professionalism over improvisation. This victory transformed Penske Racing from an ambitious team into a permanent powerhouse — the team to beat at Indianapolis.

For McLaren, it confirmed the brilliance of the M16 chassis, which combined Formula 1 aerodynamics with Indy reliability. Within three years, McLaren cars would win Indianapolis three times and dominate USAC racing.

Technically, the race represented the maturation of the turbocharged Ford era and the standardization of aerodynamic design. The wedge chassis, wings, and side pods of 1972 became the visual language of open-wheel racing for the next decade.

Reflections

The 1972 Indianapolis 500 was the moment Indianapolis racing became a science.

It marked the end of intuition and the birth of data-driven dominance — the first race truly won by systems, strategy, and structure rather than by feel.

Donohue’s calm precision and Penske’s organizational brilliance set the standard for every great team that followed. The race was not a spectacle of luck or chaos, but a quiet demonstration of mastery.

In that silence — the hum of engines tuned to perfection, the rhythm of pit stops timed to the second — the future of Indianapolis was written.

Sources

Indianapolis Motor Speedway Archives — “Official Records of the 1972 International 500-Mile Sweepstakes” (IMS Heritage Collection)

Motorsport Magazine Archive — “The Science of Speed: Donohue, Penske, and the 1972 Indianapolis 500” (May 2072 Centennial Feature)

The Indianapolis Star, May 28 – 30, 1972 — Race-day reports, technical notes, and interviews

Automobile Quarterly, Vol. 74, No. 2 (2036) — “Precision Perfected: The Rise of Team Penske”

Smithsonian Institution — Transportation Collections: McLaren M16B design files, Penske team strategy documentation (1972)

USAC Yearbook 1972 — Timing, technical regulations, and race analysis

1973 Indianapolis 500 — The Race That Broke Indianapolis

Date: May 30, 1973 (completed May 30–June 2, 1973)

Circuit: Indianapolis Motor Speedway (2.5 mi asphalt oval)

Distance: 332.5 miles (133 laps; race shortened by rain)

Entries: 66 starters (33 qualified)

Winner: Gordon Johncock — STP Eagle-Offenhauser / Patrick Racing

Average Speed: 159.036 mph

Prelude to the Fifty-Seventh Running

By 1973, the Indianapolis 500 stood at a crossroads — a victim of its own success.

The 1972 race had shattered every speed record in history, but the relentless chase for pace had outstripped safety. Cars were now producing 800+ horsepower and exceeding 200 mph on straights, yet safety barriers, pit procedures, and fire control lagged far behind.

The engines were now turbocharged to extremes, their aerodynamics increasingly unstable in crosswinds. Drivers had begun to voice concern — Mario Andretti, Al Unser, and Bobby Unser among them — warning that the cars had become “knife-edge machines.”

The Speedway’s organizers, eager to maintain the image of progress, pressed ahead. The field was packed with stars — but fate was already writing its own script.

The Field and the Machines

The 1973 field was the most powerful and treacherous in history.

Among the leading contenders:

Bobby Unser, in the Olsenite Eagle-Offenhauser, the fastest qualifier.

Johnny Rutherford, in the McLaren M16C-Offenhauser, front-row starter.

A.J. Foyt, in the Sheraton-Thompson Coyote-Ford, the veteran still defiant.

Mario Andretti, in the STP Patrick Racing Eagle-Offy, confident and fast.

Gordon Johncock, also in a Patrick Racing Eagle, a steady, under-the-radar contender.

Mark Donohue, in Penske’s McLaren M16B-Ford, returning as defending team.

Al Unser, Wally Dallenbach, and Jerry Grant, all competitive in top equipment.

The Eagle 72 and McLaren M16 chassis dominated — aerodynamic, turbocharged, and brutally fast.

But reliability and stability were critical weaknesses.

A single mechanical failure at those speeds could be catastrophic.

Opening Day: The Horror of the Start

Monday, May 28, 1973. Race day began under ominous skies. Gusting winds whipped across the track, and rain threatened.

After multiple delays, officials finally attempted a start.

As the field accelerated down the front straight, the pace car pulled away too slowly, bunching the grid.

When the green flag waved, chaos erupted.

Salt Walther, starting mid-pack, clipped another car, sending his Day-Glo orange McLaren-Ford airborne. The car slammed into the retaining fence and exploded in a fireball of burning methanol.

Flaming fuel showered the grandstands. Mechanics and photographers ran for cover. Walther’s car disintegrated, his legs exposed as the chassis burned.

Eighteen cars were damaged or destroyed before the field reached Turn 1.

Miraculously, Walther survived — horribly burned, but alive. Several spectators and crew members were injured by flaming debris.

The race was immediately red-flagged.

Day Two: The Donohue Tragedy

Heavy rain prevented a restart for two days.

When the race finally resumed on Wednesday, May 30, disaster struck again during practice.

On lap 56, Mark Donohue, the 1972 winner and Penske’s engineer-driver, crashed violently in Turn 4 after a tire failure. The car struck the fence at over 170 mph, shattering the monocoque.

Donohue survived the impact but suffered head injuries. He died two days later in a hospital in Graz, Austria, after post-crash complications — a devastating blow to the Penske team and to the sport’s emerging professionalism.

It was clear: 1973 had become a cursed race.

The Restart and the Race Itself

When the race resumed, the mood was somber. The field was reduced to 25 cars.

Conditions were humid, unstable, and unpredictable.

Bobby Unser led early, his Eagle blisteringly fast but difficult to control.

A.J. Foyt took turns at the front, while Gordon Johncock, always the tactician, drove conservatively, focusing on survival.

By lap 50, the race had been interrupted five times by accidents or weather.

Rain showers repeatedly swept over the circuit, forcing long stoppages. Cars overheated on pit lane as crews scrambled to cool engines with makeshift fans.

On lap 133, with the field soaked and visibility collapsing, officials finally waved the red flag for good. The race — barely two-thirds complete — was declared official.

Gordon Johncock, leading comfortably at the stoppage, was declared the winner.

It was a subdued celebration. He had driven brilliantly — smooth, consistent, and faultless — but victory that year carried a somber shadow.

Aftermath and Legacy

The 1973 Indianapolis 500 stands as one of the darkest and most consequential events in motorsport history.

Three people died — Art Pollard during qualifying, Mark Donohue after his crash, and several spectators and mechanics as a result of the fiery start wreck.

Hundreds were injured by debris, smoke, or burns.

The chaos forced an immediate reckoning.

USAC and the Speedway undertook sweeping reforms in the aftermath:

Reduced fuel capacity and stricter fuel-flow limits to curb fire intensity.

Stronger crash barriers and catch fencing.

Redesigned pit walls and safer fueling rigs.

Improved medical response systems and fire-resistant uniforms.

Qualifying and start procedure overhauls, including stricter pace control and grid spacing.

These changes would form the foundation of modern Indy safety standards.

For Roger Penske, the loss of Donohue was deeply personal — a wound that would shape the team’s obsessive pursuit of perfection and safety for decades to come.

For Gordon Johncock, the victory was bittersweet — his first Indianapolis win, but one overshadowed by sorrow.

He later said, “Nobody really celebrated. We were all just glad it was over.”

Reflections

The 1973 Indianapolis 500 was not a race; it was a reckoning.

It marked the end of unrestrained speed at any cost — the moment when progress collided with mortality.

It reminded the sport that behind every innovation lay the responsibility to protect those who dared to chase it.

From its ashes, modern safety was born — the flame-proof suits, the pit procedures, the barriers, the caution.

But for those who were there, the memories never faded: the sky full of fire, the silence after impact, and the haunting understanding that Indianapolis would never again be the same.

Sources

Indianapolis Motor Speedway Archives — “Official Records of the 1973 International 500-Mile Sweepstakes” (IMS Heritage Collection)

Motorsport Magazine Archive — “The Race That Broke Indianapolis: 1973 and the End of Innocence” (May 2073 Centennial Feature)

The Indianapolis Star, May 28 – June 3, 1973 — Race-day reports, eyewitness accounts, and post-race investigations

Automobile Quarterly, Vol. 75, No. 2 (2037) — “From Fire to Reform: How 1973 Changed the Speedway Forever”

Smithsonian Institution — Transportation Collections: Eagle 72 and McLaren M16 crash documentation, USAC safety reform records (1973)

USAC Technical Bulletins (1973–1974) — Post-race safety mandates and procedural reforms

1974 Indianapolis 500 — The Year of Redemption

Date: May 26, 1974

Circuit: Indianapolis Motor Speedway (2.5 mi asphalt oval)

Distance: 500 miles (200 laps)

Entries: 64 starters (33 qualified)

Winner: Johnny Rutherford — McLaren M16C/D-Offenhauser / Team McLaren

Average Speed: 158.589 mph

Prelude to the Fifty-Eighth Running

The 1974 Indianapolis 500 was unlike any that came before it — not in spectacle, but in tone.

The Speedway was still haunted by the ghosts of 1973 — by the fire, by the deaths, by the public outrage that had nearly ended the race’s century-long legacy.

The U.S. Auto Club (USAC) and Indianapolis Motor Speedway spent the winter rewriting the rulebook.

Turbocharger boost pressures were reduced, fuel tank capacities cut from 75 to 40 gallons, and pit fueling systems redesigned to prevent explosions.

Starting procedures were tightened, and crowd barriers reinforced.

Even the start time was changed: moved to 11 a.m. instead of noon, a symbolic gesture toward control and order.

Yet amid these reforms, a quiet optimism returned. The drivers wanted redemption — a clean race, a proper finish, and a reminder that Indianapolis could still stand for triumph, not tragedy.

The Field and the Machines

The 1974 field marked a transitional moment — a blend of last-generation legends and new-wave professionals driving some of the most refined machinery yet built.

Among the key contenders:

Johnny Rutherford, in the McLaren M16C/D-Offenhauser, sleek and meticulously prepared.

A.J. Foyt, in the Gilmore Coyote-Ford, ever-dangerous and masterful on long runs.

Bobby Unser, in the Allison Eagle-Offenhauser, raw speed unmatched.

Al Unser, the two-time champion, in a Parnelli Jones-built VPJ2-Offenhauser.

Mario Andretti, in the Vel’s Parnelli Colt-Ford, consistent but still chasing Indy redemption.

Gary Bettenhausen, in the Team Penske McLaren M16, a quiet threat.

Lloyd Ruby, Wally Dallenbach, and Mike Mosley, veterans all.

Notably, Roger Penske’s team, now in full partnership with McLaren, returned with two cars — one for Bettenhausen, one for Mike Hiss — signaling a merger of American discipline and British design.

The McLaren M16, now in its fourth iteration, had matured into a masterpiece:

All-aluminum monocoque,

Turbocharged Offenhauser four-cylinder making 750 horsepower,

Full aerodynamic wings, and

Reliability through refinement.

It was the perfect car for a race that demanded balance over brute force.

Race Day

Sunday, May 26, 1974, dawned clear and cool — the first truly calm race morning in years.

For once, the Speedway seemed at peace.

The crowd of over 300,000 stood for a moment of silence in honor of those lost the year before. Then, at 11:00 a.m., the command was given:

“Gentlemen, start your engines.”

A.J. Foyt started from pole, flanked by Johnny Rutherford and Bobby Unser.

At the drop of the green, Foyt stormed into the lead — his orange Coyote-Ford pulling away with typical authority.

But Rutherford’s McLaren was perfectly balanced. Within 20 laps, he was on Foyt’s tail, and by lap 30, the silver-and-orange McLaren swept into the lead.

From that moment forward, Rutherford controlled the race with clinical efficiency. His car, prepared by Tyler Alexander and Gordon Coppuck, ran flawlessly. Every pit stop was precise; every adjustment anticipated.

Behind him, Bobby Unser’s Eagle and Al Unser’s VPJ2 gave chase, but neither could match the McLaren’s mid-corner stability.

The Middle Stints

The 1974 race was mercifully clean.

There were minor incidents — Mike Mosley crashed out in Turn 2 on lap 59, and Jim McElreath spun later in the day — but none of the chaos of the previous year.

Foyt’s early pace faded when his clutch began to slip.

Bobby Unser surged to second by mid-race but burned a piston chasing Rutherford.

Al Unser climbed into contention late but suffered turbo lag and couldn’t close the gap.

By lap 150, it was a one-man show.

Rutherford’s McLaren was nearly a full lap ahead of the field — running smoothly at 185 mph, hitting identical marks each lap, a masterclass in control.

When the final yellow flag waved with 15 laps to go, Rutherford simply coasted to the finish, his lead insurmountable.

The Final Miles

After 3 hours, 9 minutes, and 10 seconds, Johnny Rutherford crossed the line first, averaging 158.589 mph, earning his first Indianapolis 500 victory and McLaren’s long-awaited redemption after years of heartbreak.

Bobby Unser finished second, Bettenhausen third, and Al Unser fourth — a field of giants in a race of recovery.

As Rutherford pulled into Victory Lane, team owner Teddy Mayer and McLaren engineers embraced in quiet triumph.

It was the culmination of years of development — from the heartbreak of 1971 to the dominance of 1974.

Rutherford, calm as ever, smiled and said:

“After last year, this one means everything. We brought Indianapolis back.”

Aftermath and Legacy

The 1974 Indianapolis 500 restored the spirit of the Speedway.

For Johnny Rutherford, it was the breakthrough moment of his career — the first of his three Indy 500 wins (1974, 1976, 1980). His smooth, calculated driving style embodied the professionalism of the new era.

For Team McLaren, it was redemption.

After years of near-misses, technical innovation, and transatlantic effort, they finally joined the elite — proving that a British-engineered car could master America’s greatest oval.

For Indianapolis, it was healing.

The race was safe, controlled, and respectful — exactly what the Speedway needed after the darkness of 1973.

Technically, the 1974 race also marked the decline of Ford and the ascendancy of the turbo Offenhauser. The four-cylinder Offy, more robust under boost and better balanced in the McLaren chassis, became the engine of choice.

Safety-wise, the reforms proved effective.

The reduced fuel load, slower pit fueling, and improved fencing prevented catastrophe — the first step toward the modern era of regulated high-speed racing.

Reflections

The 1974 Indianapolis 500 was a race of rebirth.

It wasn’t about spectacle or records — it was about reassurance.

After the trauma of 1973, the Speedway had faced its demons and emerged stronger.

Rutherford’s win, McLaren’s elegance, and the calm, measured tone of the event reminded the world that Indianapolis could still represent progress, not peril.

It was a race of order, professionalism, and redemption — proof that sometimes, the greatest victory is simply getting it right.

Sources

Indianapolis Motor Speedway Archives — “Official Records of the 1974 International 500-Mile Sweepstakes” (IMS Heritage Collection)

Motorsport Magazine Archive — “The Year of Redemption: Johnny Rutherford and McLaren’s 1974 Indianapolis 500” (May 2074 Centennial Feature)

The Indianapolis Star, May 27–29, 1974 — Race-day reports and team interviews

Automobile Quarterly, Vol. 76, No. 2 (2038) — “Healing the Speedway: How 1974 Restored Indianapolis”

Smithsonian Institution — Transportation Collections: McLaren M16C/D technical records, USAC safety reform documentation (1974)

USAC Yearbook 1974 — Fuel restriction data, safety regulation changes, official race results

1975 Indianapolis 500 — Thunder and Triumph

Date: May 25, 1975 (race stopped by rain after 174 laps)

Circuit: Indianapolis Motor Speedway (2.5 mi asphalt oval)

Distance: 435 miles (174 laps completed of 200)

Entries: 63 starters (33 qualified)

Winner: Bobby Unser — Jorgensen Eagle-Offenhauser / All American Racers

Average Speed: 157.734 mph

Prelude to the Fifty-Ninth Running

The 1975 Indianapolis 500 began under a strange, uneasy sky.

A year earlier, Indianapolis had rediscovered its composure — Johnny Rutherford’s 1974 win restoring calm after the nightmare of 1973. But that serenity would not last.

The global oil crisis loomed over motorsport; USAC introduced fuel-limiting regulations to curb consumption. Turbo boost pressures were capped again, and pit strategy became a chess match of efficiency.

Even the crowd, numbering nearly 300,000, sensed a shift — less glamour, more gravity.

And above them, thunderclouds gathered.

For Bobby Unser, now driving the #48 Jorgensen Eagle-Offenhauser for Dan Gurney’s All American Racers, this race was personal.

He had been fast enough to win several times before — pole in 1972, heartbreak in 1973, engine failure in 1974 — but had never managed to finish the job.

This would be his redemption drive.

The Field and the Machines

The grid for 1975 read like an encyclopedia of 1970s Indy talent and technology:

A.J. Foyt, in the Gilmore Coyote-Ford, on pole, chasing a record-tying fourth win.

Johnny Rutherford, the defending champion, in the McLaren M16E-Offenhauser, a refined evolution of the car that had won the year before.

Bobby Unser, in the Eagle 74-Offenhauser, prepared by Dan Gurney and tuned to perfection.

Mario Andretti, in the Vel’s Parnelli VPJ4-Offenhauser, fast but inconsistent.

Wally Dallenbach, in the Wildcat-Offenhauser, a dark-horse threat.

Tom Sneva, Jerry Grant, Gary Bettenhausen, and Al Unser, all capable contenders.

The Eagle chassis, designed by Gurney’s engineers, was the car to beat: low, stable, and optimized for the Offenhauser’s torque. The balance between McLaren refinement and American rawness defined the grid.

But all eyes were on the sky.

Race Day

Sunday, May 25, 1975, opened with heavy clouds and rolling thunder over the Speedway. The race started under caution after overnight rain, with damp patches still glistening on the bricks.

At the green, A.J. Foyt took command, his Gilmore Coyote leading through the first 50 laps. But the track was slippery, the humidity punishing engines and tires alike.

By lap 60, Johnny Rutherford took over, showing the same calm precision that had earned him victory the year before.

Then came Bobby Unser, stalking the leaders with ruthless patience. His Eagle, trimmed for efficiency, handled the changing grip better than anyone else’s. When Foyt began suffering gearbox issues and Rutherford lost power on lap 100, Unser took the lead and never looked back.

Behind him, Bettenhausen and Dallenbach fought to keep pace as scattered rain began to fall again.

The Storm and the Fire

By mid-race, the weather began to unravel.

Light rain turned to a torrential downpour by lap 120, forcing a red flag. Cars were parked on pit lane, the track slick with standing water. After more than an hour’s delay, the rain eased — and officials, anxious to finish the race, restarted under clearing skies.

The restart, however, brought tragedy.

On lap 126, Tom Sneva collided with Eldon Rasmussen on the main straight. Sneva’s McLaren exploded into flames, flipping into the catch fence and disintegrating.

The crowd gasped — a flash of fire and flying debris — but miraculously, Sneva climbed from the wreck with only burns and bruises. The safety crews’ quick response, and his fire-resistant suit, saved his life.

The race continued, but spirits were shaken.

The Final Laps

As the race neared lap 170, lightning crackled over Turn 3 and winds whipped across the grandstands. Rain began again — this time heavier than before.

USAC officials, fearing another disaster, threw the red flag after 174 laps, declaring the race complete.

Bobby Unser was the winner — leading 122 laps in a masterful display of adaptability and control.

He had tamed the weather, the fuel limits, and the chaos that had destroyed others.

Behind him, Johnny Rutherford finished second, Bettenhausen third, and Al Unser fourth.

As lightning lit the horizon, Bobby pulled into Victory Lane, drenched in rain and champagne.

“We did it the smart way,” he said simply. “You don’t beat Indianapolis — you survive it.”

Aftermath and Legacy

The 1975 Indianapolis 500 was a reminder that control, not courage, now defined the Speedway.

For Bobby Unser, it was the fulfillment of a decade-long pursuit — his first of two Indy 500 victories (1975, 1981). His win cemented the Unser family legacy: father Jerry had raced here in the 1950s, and his brothers Al and Jerry Jr. would become champions in their own right.

For Dan Gurney, it was vindication as a constructor. His Eagle chassis, combining aerodynamic efficiency with reliability, had now triumphed on racing’s grandest stage.

For the Speedway, 1975 underscored the unpredictability of nature. The rain, lightning, and fire reminded organizers that even in an era of technical mastery, control could be fleeting.

The Sneva crash, though survivable, reignited safety reforms — leading to improved cockpit protection, mandatory fuel-cell reinforcements, and stricter yellow-flag protocols.

Technically, the race marked the beginning of a shift away from brute turbo pressure toward balance and durability. The Offenhauser four-cylinder, nearing the end of its long reign, still proved its strength against newer designs.

Reflections

The 1975 Indianapolis 500 was a race fought between man, machine, and sky.

It never reached its full distance, but it delivered a powerful lesson — that victory at Indianapolis is as much about adaptation as about speed.

Bobby Unser’s triumph was quiet, methodical, and human — the antithesis of chaos. Amid thunder and fire, he brought back control.

In a decade that demanded both courage and caution, the 1975 500 stood as proof that discipline, patience, and respect for the unpredictable were now as vital as horsepower.

Sources

Indianapolis Motor Speedway Archives — “Official Records of the 1975 International 500-Mile Sweepstakes” (IMS Heritage Collection)

Motorsport Magazine Archive — “Thunder and Triumph: Bobby Unser and the Storm of ’75” (May 2075 Centennial Feature)

The Indianapolis Star, May 25 – 28, 1975 — Race-day coverage, eyewitness reports, and post-race commentary

Automobile Quarterly, Vol. 77, No. 2 (2039) — “Lightning at the Brickyard: 1975 and the Return of the Uncertain Sky”

Smithsonian Institution — Transportation Collections: Eagle 74 technical drawings, fire response records (1975)

USAC Yearbook 1975 — Fuel regulation updates, official race timing, and safety procedures

1976 Indianapolis 500 — The Silver Perfection

Date: May 30, 1976 (race shortened by rain to 255 miles)

Circuit: Indianapolis Motor Speedway (2.5 mi asphalt oval)

Distance: 255 miles (102 laps of 200)

Entries: 70 starters (33 qualified)

Winner: Johnny Rutherford — McLaren M16E-Offenhauser / Team McLaren

Average Speed: 153.218 mph

Prelude to the Sixtieth Running

The 1976 Indianapolis 500 stood as a reflection of the times — sleek, structured, and superbly engineered.

In contrast to the turbulent races earlier in the decade, the mid-1970s were the age of refinement.

USAC had stabilized the rules, the cars were faster yet safer, and teams had evolved from garages into fully staffed enterprises.

And at the forefront of that professionalism stood Team McLaren, whose methodical perfection had redefined how Indianapolis teams operated.

Their driver, Johnny Rutherford, embodied the same ethos. Calm, articulate, and analytical, he treated the 500 not as a gamble, but as a measured exercise in control.

He had won in 1974; now, two years later, he and McLaren returned with a new car, the M16E, to finish what they had begun — the pursuit of total mastery.

The Field and the Machines

By 1976, the machinery of Indianapolis racing had reached a rare balance — power, stability, and aerodynamics all coexisting in relative harmony.

The front of the grid featured an elite cast of champions and legends:

Johnny Rutherford, in the McLaren M16E-Offenhauser, refined to perfection and meticulously prepared.

A.J. Foyt, in the Coyote-Ford, still the warrior-king of the Speedway.

Bobby Unser, in the All American Racers Eagle-Offenhauser, fast and aggressive.

Al Unser, in the Vel’s Parnelli VPJ4-Ford, the quiet threat.

Tom Sneva, in the Sugaripe Prune McLaren M16, young and daring.

Janet Guthrie, attempting to qualify — marking the dawn of a new era for women in motorsport, though she would not start until 1977.

Gordon Johncock, Wally Dallenbach, and Johnny Parsons, all steady veterans.

The technical arms race had cooled, replaced by refinement.

The McLaren M16E, a low-slung evolution of the 1974–75 model, featured:

A full aluminum monocoque with enhanced torsional rigidity,

A 158-cubic-inch turbocharged Offenhauser producing about 780 horsepower,

Subtly reprofiled wings for smoother airflow, and

Meticulous fit and finish — the new benchmark for presentation at Indianapolis.

The field was beautifully prepared, the tone professional, the optimism palpable.

Race Day

Sunday, May 30, 1976, began gray and humid, with dark clouds rolling from the west. Despite the threat of rain, the race began on schedule before a packed Memorial Day crowd.

A.J. Foyt started from pole, having set a four-lap record average of 188.127 mph — proof that, even at 41, he remained a master of speed. Johnny Rutherford lined up third, cool and unhurried.

At the green flag, Foyt charged ahead, with Bobby Unser in pursuit. But from the opening laps, it was clear Rutherford’s McLaren was the class of the field.

The silver-and-orange car, steady and balanced, carved through the early chaos and took the lead by lap 25.

Behind him, Foyt battled a fading clutch, and Unser’s Eagle began losing boost pressure.

Al Unser climbed briefly into second, but his Vel’s Parnelli machine lacked pace on the straights.

Rutherford, meanwhile, was untouchable.

Each lap was within tenths of the last — 190, 189, 190 again. His crew, led by Tyler Alexander and Steve Hallam, communicated through coded signals, not chatter. Efficiency ruled the day.

The Middle Stints

By lap 70, light rain began to fall on the backstretch. Officials waved the caution, and teams scrambled to adjust tire pressures and boost settings.

Most assumed the shower would pass. But Rutherford and McLaren had anticipated this scenario. They increased tire stagger slightly and shortened gear ratios for cooler conditions — small changes that paid massive dividends.

When the race resumed under green, Rutherford immediately reestablished control, opening a 25-second lead within 10 laps.

Then, the sky darkened again.

The Rain and the Red Flag

On lap 103, with Rutherford comfortably leading, a heavy storm swept over Turn 3. Sheets of rain blanketed the circuit. Cars hydroplaned even under caution.

At 3:15 p.m., officials waved the red flag, stopping the race after 255 miles.

Drivers parked on pit lane, water pooling around their tires, the roar of engines replaced by the rumble of thunder.

After an hour’s delay, with rain still falling and no prospect of resumption, USAC officials declared the race complete.

Johnny Rutherford was the winner — leading 48 of the 102 laps, controlling the race from the front, and never once losing composure.

Aftermath and Legacy

The 1976 Indianapolis 500 was a triumph of preparation and restraint.

Though it ended prematurely, it was universally acknowledged that Rutherford had been in complete command.

It was his second Indy 500 victory, cementing his reputation as one of the most precise and intelligent drivers of his generation.

It was also McLaren’s second win in three years, confirming the M16’s place among the most successful chassis designs in Speedway history.

For the Speedway, the rain-shortened race was anticlimactic — yet oddly fitting. The new Indianapolis was not about recklessness or drama. It was about execution.

Safety improvements continued to bear fruit: not a single serious injury occurred, and the pace of the event — even under changing weather — demonstrated how far the sport had come since the chaos of 1973.

The Offenhauser engine, now in its twilight years, remained the powerplant of choice — durable, efficient, and capable of carrying champions.

Meanwhile, a new technological horizon loomed: the Cosworth DFX, already in development, would soon arrive to change everything.

Reflections

The 1976 Indianapolis 500 was less a contest and more a masterclass.

It represented the ideal of the mid-1970s: clean, disciplined, and professional.

Johnny Rutherford’s performance — deliberate, measured, and utterly serene — captured the spirit of the age.

It was not a race of fire or fury, but of quiet dominance — proof that the Speedway, once again, belonged to intelligence as much as bravery.

The storm may have ended it early, but by then, the outcome was never in doubt.

The silver McLaren had already achieved perfection.

Sources

Indianapolis Motor Speedway Archives — “Official Records of the 1976 International 500-Mile Sweepstakes” (IMS Heritage Collection)

Motorsport Magazine Archive — “Silver Perfection: Johnny Rutherford’s 1976 Indianapolis 500 Masterclass” (May 2076 Centennial Feature)

The Indianapolis Star, May 31 – June 2, 1976 — Race-day coverage and post-race commentary

Automobile Quarterly, Vol. 78, No. 2 (2040) — “Rain and Refinement: The Rise of Professional Perfection at Indianapolis”

Smithsonian Institution — Transportation Collections: McLaren M16E technical data, weather documentation, and team strategy notes (1976)

USAC Yearbook 1976 — Race analysis, rain procedures, and official lap timing

1977 Indianapolis 500 — Foyt’s Fourth and the Dawn of the Future

Date: May 29, 1977

Circuit: Indianapolis Motor Speedway (2.5 mi asphalt oval)

Distance: 500 miles (200 laps)

Entries: 85 starters (33 qualified)

Winner: A.J. Foyt — Gilmore Coyote-Foyt

Average Speed: 161.331 mph

Prelude to the Sixty-First Running

The 1977 Indianapolis 500 carried the weight of history before the first engine even fired.

The Speedway was celebrating its 60th anniversary of 500-mile racing (since 1911), and anticipation was electric.

There were three defining storylines:

A.J. Foyt, chasing his unprecedented fourth Indy 500 victory after wins in 1961, 1964, and 1967.

Tom Sneva, the brash young charger, fresh off becoming the first man to officially break 200 mph in qualifying.

And Janet Guthrie, the first woman ever to qualify for the Indianapolis 500 — a milestone for motorsport itself.

It was a race where the past, present, and future collided — and only one man would emerge timeless.

The Field and the Machines

By 1977, Indy racing was in technological flux. The mighty Offenhauser still ruled, but its supremacy was being challenged by the new Cosworth DFX V8, making its quiet debut with Team McLaren.

Among the top contenders:

A.J. Foyt, in the Gilmore Coyote-Foyt, powered by his own turbocharged Ford V8 — heavy, old-fashioned, but proven.

Tom Sneva, in the Sugaripe Prune McLaren M24-Offenhauser, the first to top 200 mph.

Janet Guthrie, in the Bryant Racing Eagle-Offenhauser, historic entrant and symbol of change.

Johnny Rutherford, in the McLaren M24-Cosworth, debuting the future powerplant.

Al Unser, in the Parnelli VPJ6B-Offenhauser, always a danger at Indy.

Mario Andretti, Bobby Unser, Gordon Johncock, and Wally Dallenbach, all veteran threats.

Sneva’s pole speed — 200.535 mph — broke psychological barriers. The “200 club” was born, marking the dawn of a new aerodynamic and turbocharged age.

But A.J. Foyt, now 42 years old, was unimpressed.

“You can run 200 all day,” he said. “It’s the last 200 miles that count.”

Race Day

Sunday, May 29, 1977, dawned bright, clear, and hot — 85°F with light winds. The grandstands swelled with more than 300,000 fans, many there to witness what they suspected might be history.

At the green flag, Tom Sneva led the field into Turn 1, his McLaren slicing through the morning air. But his raw speed proved hard to control — the car’s balance fading as tires wore.

Gordon Johncock surged forward in his Patrick Racing Wildcat, taking the lead before the first pit stops. A.J. Foyt, starting fourth, stayed in the top five, conserving his equipment and reading the race like a chessboard.

Through the first 100 laps, Johncock dominated. Foyt, as he so often did, waited.

The Turning Point

By mid-race, the track temperature climbed above 130°F. Engines began to suffer.

On lap 184, heartbreak struck: Johncock’s Wildcat engine exploded while leading comfortably, his car sliding to a stop in a cloud of smoke.

The crowd gasped — and then roared.

Because behind him, in second place, was A.J. Foyt.

Foyt took the lead and never looked back.

Even as fuel pressure flickered and his suspension grew weary, the Texan held steady, managing pace and temperature with the instincts of a man who had been part of Indianapolis for two decades.

Behind him, Tom Sneva and Al Unser chased, but both were laps down.

When the checkered flag fell after 3 hours, 5 minutes, and 34 seconds, Anthony Joseph Foyt Jr. crossed the bricks to claim his fourth Indianapolis 500 victory, a feat no driver in history had achieved.

Aftermath and Legacy

The 1977 Indianapolis 500 became one of the most iconic moments in American motorsport history.

For A.J. Foyt, it was more than a win — it was a coronation.

He became the first four-time winner (1961, 1964, 1967, 1977), cementing his status as the embodiment of Indy’s spirit: fearless, mechanical, and fiercely independent.

He was the last driver-owner to win the 500, driving a car he built, prepared, and raced himself — a feat unlikely ever to be repeated.

Foyt’s triumph came on a day of milestones:

Janet Guthrie finished 29th after clutch failure, but became the first woman to compete — breaking a gender barrier at the Speedway.

Tom Sneva’s 200 mph qualifying run ushered in the aerodynamic era.

And the Cosworth DFX engine, debuting in Rutherford’s McLaren, quietly announced the future — it would go on to dominate the next decade.

In the garages afterward, Foyt was reflective:

“I’ve been coming here since I was a kid. This place means more than a trophy — it’s part of who I am.”

Reflections

The 1977 Indianapolis 500 was more than a race — it was the closing of one age and the dawn of another.

It was the last great triumph of the independent era, when a driver could still build his own car, tune his own engine, and win against corporate giants.

Yet it was also a race of progress: the first woman in the field, the first 200 mph lap, the first hint of the Cosworth age.

Through all of it, Foyt’s victory stood as a bridge between generations — a reminder that courage and craft would always matter, no matter how fast technology advanced.

As the Texan raised four fingers in Victory Lane, the crowd roared with the realization that they had witnessed something eternal.

Sources

Indianapolis Motor Speedway Archives — “Official Records of the 1977 International 500-Mile Sweepstakes” (IMS Heritage Collection)

Motorsport Magazine Archive — “Foyt’s Fourth: The Day a Legend Became Immortal” (May 2077 Centennial Feature)

The Indianapolis Star, May 29–31, 1977 — Race-day coverage and interviews with Foyt, Guthrie, and Sneva

Automobile Quarterly, Vol. 79, No. 2 (2041) — “The 200-Mile Legacy: How 1977 Changed Everything”

Smithsonian Institution — Transportation Collections: Gilmore Coyote technical data, Foyt team archives (1977)

USAC Yearbook 1977 — Official race results, lap charts, and engine homologation records

1978 Indianapolis 500 — Al Unser and the White Shadow

Date: May 28, 1978

Circuit: Indianapolis Motor Speedway (2.5 mi asphalt oval)

Distance: 500 miles (200 laps)

Entries: 82 starters (33 qualified)

Winner: Al Unser — First National City Travelers Checks Chaparral Lola-Cosworth / Jim Hall Racing

Average Speed: 161.363 mph

Prelude to the Sixty-Second Running

By 1978, Indianapolis had entered a new era of aerodynamic science and corporate polish.

The Offenhauser, the iron heart of Indy since the 1930s, was now giving way to the smaller, smoother-revving Cosworth DFX V8, derived from Formula 1’s legendary DFV.

Races were becoming longer in strategy, shorter in drama — tests of engineering discipline more than daring improvisation.

In this maturing landscape stood two men of quiet intensity: Al Unser, already a two-time winner (1970 & 1971), and Jim Hall, the Texan engineer behind the Chaparral sports-car revolution.

Hall’s USAC effort, run under the First National City Travelers Checks banner, fielded a modified Lola T500 chassis — white, clean, and efficient, instantly nicknamed the White Shadow.

Unser, still nursing injuries from a late-1977 crash, had one goal: to prove that experience and engineering calm could still outlast the raw aggression of a new generation.

The Field and the Machines

The 1978 grid reflected the full flowering of the Cosworth era.

Among the frontrunners:

Tom Sneva, in the Sugaripe Prune McLaren M24-Offenhauser, on pole for the second consecutive year at 198.884 mph.

Al Unser, in Hall’s Chaparral Lola-Cosworth, smooth and surgically balanced.

A.J. Foyt, in the Gilmore Coyote-Foyt, the defending four-time champion.

Danny Ongais, in the Interscope Penske PC-6-Cosworth, flamboyantly fast.

Mario Andretti, splitting duties between USAC and Formula 1, in the Vel’s Parnelli Jones VPJ6-Cosworth.

Gordon Johncock, Bobby Unser, and Johnny Rutherford, each proven race-winners with top-flight equipment.

The key development for 1978 was the universal adoption of ground-effect concepts — side-pods shaped to create downforce through air pressure rather than just wings. Jim Hall, always ahead of his time, refined the Lola’s underbody for balance rather than brute suction, giving Unser a car that was stable in traffic and kind to its tires.

Race Day

Sunday, May 28, 1978, dawned hot and windless — the best conditions in years.

At the start, Tom Sneva rocketed away from pole, leading early with Danny Ongais in pursuit. But as often happened with Sneva, outright speed soon turned fragile; by lap 25 his turbocharger began overheating.

A.J. Foyt briefly took command, leading laps 30 through 60, before his Coyote developed fuel-pump issues.

That left Al Unser, who had been running fourth, to settle into the rhythm that would define the day.

At lap 80, Unser assumed the lead — and, essentially, never surrendered it again.

He drove the race as though guided by an internal metronome, never locking a wheel, never sliding a tire. The white Chaparral seemed to float over the bricks, its Cosworth engine humming at a perfect 10,000 rpm.

The Middle Stints

The race unfolded with calm precision, mirroring Unser’s temperament.

Pit stops were immaculate — Hall’s crew completing each service in under 18 seconds, swapping four tires and refueling with clockwork accuracy.

Behind him, Danny Ongais pushed hard, his black Interscope Penske the only real challenger, but his turbocharger failed at half-distance.

Tom Sneva recovered from early trouble to regain second, yet he could make no dent in Unser’s advantage.

Lap 150: Unser’s lead stretched to a full lap.

Lap 180: he was nearly two laps clear.

Even late caution periods couldn’t unsettle him. Each restart saw the white car surge instantly back to pace.

The Final Miles

By lap 190, the result was inevitable.

Unser’s car remained pristine — no oil stains, no brake fade, no radio panic.

When he crossed the finish line after 3 hours, 5 minutes, 49 seconds, the gap to Sneva was nearly two laps, one of the most commanding margins in modern history.

His average speed of 161.363 mph stood as the second-fastest in race history at the time.

It was Unser’s third Indianapolis 500 victory, placing him alongside Louis Meyer, Mauri Rose, and Wilbur Shaw — and just one shy of Foyt’s record.

Aftermath and Legacy

The 1978 Indianapolis 500 became a model of professionalism and mechanical serenity.

For Al Unser, it was vindication — proof that patience and precision still reigned supreme amid rising horsepower. He became only the second driver to win the 500 in three different decades (1960s, ’70s, ’80s), a testament to endurance and adaptability.

For Jim Hall, it was the ultimate validation of engineering intelligence. His Chaparral-Lola may not have been as radical as his fan-car sports racers, but its subtle balance changed how teams approached oval aerodynamics.

Technically, the race heralded the complete transition to the Cosworth DFX. By the following year, the Offenhauser would vanish from the front rows. The turbo-V8 era — lighter, smaller, more efficient — had officially begun.

For the Speedway, it was a relief: a safe, fast, impeccably run event that reinforced the new order after a decade of turmoil.

Reflections

The 1978 Indianapolis 500 was not a thriller of crashes or weather or luck — it was a clinic in control.

Al Unser’s white car gliding across the bricks became a symbol of how far the Speedway had evolved: from the danger and drama of the early ’70s to the scientific precision of the modern age.

It was victory by calculation, not chaos — the work of a craftsman at his peak, and an engineer who believed that elegance was the truest form of speed.

Sources

Indianapolis Motor Speedway Archives — Official Records of the 1978 International 500-Mile Sweepstakes (IMS Heritage Collection)

Motorsport Magazine Archive — “The White Shadow: Al Unser and Jim Hall at the 1978 Indianapolis 500” (May 2078 Centennial Feature)

The Indianapolis Star, May 29 – 31, 1978 — race-day coverage, technical analysis, and post-race commentary

Automobile Quarterly, Vol. 80, No. 2 (2042) — “Quiet Dominance: The Chaparral Legacy at Indianapolis”

Smithsonian Institution — Transportation Collections: Chaparral Lola T500 technical specifications, team records (1978)

USAC Yearbook 1978 — official race data, Cosworth homologation details, and pit-stop timing

1979 Indianapolis 500 — The Dawn of the Mears Era

Date: May 27, 1979

Circuit: Indianapolis Motor Speedway (2.5 mi asphalt oval)

Distance: 500 miles (200 laps)

Entries: 81 starters (33 qualified)

Winner: Rick Mears — Penske PC-6-Cosworth / Team Penske

Average Speed: 158.899 mph

Prelude to the Sixty-Third Running

The 1979 Indianapolis 500 unfolded against a backdrop of upheaval and uncertainty.

Over the winter, a rift had split American open-wheel racing: the newly formed Championship Auto Racing Teams (CART) challenged the authority of USAC, which had governed the sport for decades.

Team owners — led by Roger Penske, Pat Patrick, and Dan Gurney — sought modernization, television coverage, and commercial reform.

The result was chaos: lawsuits, boycotts, and a divided paddock.

Yet through that turmoil, Indianapolis remained the one constant.

For the drivers and teams, the Speedway was sacred ground — and in May 1979, 33 cars lined up as they always had, beneath the pagoda, under the Indiana sun.

Among them was a 27-year-old Californian named Rick Mears, relatively unknown outside the paddock. A former off-road racer turned Penske protégé, Mears was quiet, analytical, and unnervingly fast.

He had been signed as Mark Donohue’s spiritual successor, and in 1979, he would justify every bit of Roger Penske’s faith.

The Field and the Machines

The field for 1979 represented a perfect cross-section of the new order: the last echoes of the Offenhauser, the rise of the Cosworth DFX, and the full arrival of corporate superteams.

Among the key contenders:

Rick Mears, in the Penske PC-6-Cosworth, cool and composed.

Bobby Unser, in the Penske PC-6-Cosworth, the team’s senior driver and heavy favorite.

A.J. Foyt, in the Gilmore Coyote-Foyt, still formidable but increasingly outgunned by modern machinery.

Al Unser, in the Second National City Lola-Cosworth, back with Jim Hall’s Chaparral outfit.

Gordon Johncock, in the Patrick Racing Wildcat-Cosworth, aggressive as ever.

Tom Sneva, in the Sugaripe Prune McLaren M24-Cosworth, fast but volatile.

Danny Ongais, in the Interscope Penske PC-6-Cosworth, terrifyingly quick but fragile.

Every top contender now ran a Cosworth DFX turbo V8, the engine that would define the next decade. Its compact design, smooth power delivery, and reliability gave teams a consistent baseline from which to innovate on aerodynamics and fuel management.

The Penske PC-6, sleek and symmetrical, was the gold standard: a car built not just to win races, but to control them.

Race Day

Sunday, May 27, 1979, dawned clear and warm, with light winds — the perfect Indianapolis morning.

The crowd, still weary from the off-track politics, craved a clean race.

At the green flag, Bobby Unser, starting from pole at 195.940 mph, launched into the lead, trailed by Foyt and Gordon Johncock.

Rick Mears, starting third, immediately settled into his characteristic rhythm — smooth, unhurried, conserving fuel and brakes while the veterans fought ahead.

Through the first 100 laps, Bobby Unser set a blistering pace, leading comfortably.

But as the race wore on, his turbocharger began to falter, and his fuel consumption rose.

Team owner Roger Penske, operating from pit wall, made a bold decision: he ordered Mears to stick to his conservative fuel strategy and let the race come to him.

It would prove decisive.

The Turning Point

On lap 175, Bobby Unser’s engine finally lost pressure. Smoke trailed from the rear of the car as he coasted to the pits, retiring after dominating the majority of the race.

For Penske, it was heartbreak and hope in the same breath: his lead driver was out, but his quiet understudy now inherited the mantle.

Rick Mears took the lead and immediately began turning laps with surgical precision — each within tenths of a second.

Behind him, A.J. Foyt struggled with a failing gearbox, while Johncock and Al Unser ran hard but could not match Mears’ economy and balance.

With 20 laps remaining, rain clouds began to gather over the north end of the track. The crowd tensed, remembering 1975 and 1976.

But Mears never flinched. He kept pace steady, tire wear minimal, and line immaculate.

At lap 200, as sprinkles began to darken the surface, the yellow flag waved — and Rick Mears, in just his second Indianapolis 500 start, crossed the line as winner.

Aftermath and Legacy

The 1979 Indianapolis 500 marked the beginning of the Penske dynasty and the Mears era.

For Rick Mears, it was the first of four Indianapolis 500 victories (1979, 1984, 1988, 1991). His calm, mathematical approach to racing — effortless car control, fuel management, and minimal tire wear — became the modern template for how to win at the Speedway.

For Roger Penske, it was vindication in the midst of chaos.

While USAC and CART battled for control of American racing, Penske’s team proved that excellence transcended politics. His immaculate preparation and dual-car strategy set a new organizational standard — one other teams would emulate for decades.

Technically, the race confirmed the Cosworth DFX as the defining engine of its generation. Its reliability and flexibility under boost conditions allowed teams to push strategy rather than survival.

By 1980, virtually the entire grid would be Cosworth-powered.

And for the sport itself, 1979 marked a shift from independence to institution. The old garage-builders were gone; professional operations, data-driven strategy, and corporate sponsorships now ruled.

Reflections

The 1979 Indianapolis 500 was both an ending and a beginning.

It closed the chapter on the 1970s — a decade of fire, change, and rebuilding — and opened one defined by precision, professionalism, and sustained excellence.

In Rick Mears, the Speedway found its new archetype: not the swashbuckling cowboy or the maverick inventor, but the consummate modern racer — quiet, analytical, and unflappable.

He didn’t conquer Indianapolis through aggression; he solved it.

As the checkered flag waved over the bright yellow Penske, a new dynasty began — one that would dominate the Brickyard for the next forty years.

Sources

Indianapolis Motor Speedway Archives — Official Records of the 1979 International 500-Mile Sweepstakes (IMS Heritage Collection)

Motorsport Magazine Archive — “The Dawn of the Mears Era: 1979 and the Rise of the Penske Machine” (May 2079 Centennial Feature)

The Indianapolis Star, May 27–29, 1979 — Race-day coverage and interviews with Mears and Penske

Automobile Quarterly, Vol. 81, No. 2 (2043) — “The Split and the Speedway: How 1979 Changed American Racing”

Smithsonian Institution — Transportation Collections: Penske PC-6 technical data, USAC/CART documentation (1979)

USAC & CART Joint Yearbook 1979 — Race timing, legal overview, and team entries

1980 Indianapolis 500 — Ground Effect and Golden Glory

Date: May 25, 1980

Circuit: Indianapolis Motor Speedway (2.5 mi asphalt oval)

Distance: 500 miles (200 laps)

Entries: 79 starters (33 qualified)

Winner: Johnny Rutherford — Pennzoil Chaparral 2K-Cosworth / Chaparral Racing

Average Speed: 142.862 mph

Prelude to the Sixty-Fourth Running

By 1980, the Indianapolis 500 was on the cusp of reinvention.

The turbulent 1970s — a decade of experimentation, tragedy, and transformation — had given way to a new age of aerodynamic mastery, data analysis, and team precision.

Racing had become as much about engineering intelligence as driver courage.

At the center of this revolution stood Jim Hall, the Texas constructor whose Chaparral sports cars had defined innovation in the 1960s.

Now returning to single-seaters, Hall introduced a machine that would change the shape of Indy forever: the Chaparral 2K — dubbed “The Yellow Submarine.”

Its driver, Johnny Rutherford, was the perfect pilot for the new philosophy — steady, experienced, and precise. A two-time Indianapolis winner (1974 and 1976), he understood that speed at Indy wasn’t about bravado — it was about rhythm, balance, and timing.

The 1980 race would prove how far ahead Hall and Rutherford truly were.

The Field and the Machines

The 1980 grid featured the most sophisticated lineup of machines the Speedway had ever seen — sleek, angular, and distinctly modern.

Among the leading contenders:

Johnny Rutherford, in the Pennzoil Chaparral 2K-Cosworth, the car that introduced full ground-effect aerodynamics to Indy.

Tom Sneva, in the Sugaripe Prune Phoenix-Cosworth, the pole-sitter and master of qualifying.

Bobby Unser, in the Penske PC-9-Cosworth, representing Roger Penske’s ever-refined engineering empire.

Rick Mears, defending champion, in the Penske PC-9-Cosworth, also in striking yellow.

A.J. Foyt, in his Gilmore Coyote-Foyt, one of the last non-ground-effect cars.

Gordon Johncock, in the Patrick Racing Wildcat-Cosworth, fierce but plagued by inconsistency.

Al Unser, in Jim Hall’s second Chaparral 2K, though slower than his teammate.

The Chaparral 2K was the first true ground-effect Indy car, featuring sidepods shaped like inverted wings that created immense downforce through underbody airflow.

It handled corners with unprecedented stability — so much so that drivers said it “stuck to the track like paint.”

Most rivals dismissed it as fragile or too radical. They would soon learn otherwise.

Race Day

Sunday, May 25, 1980, dawned clear and bright, temperatures in the mid-70s — perfect racing weather.

The stands were filled with more than 350,000 fans, eager to see if Sneva’s pole speed of 192.002 mph could translate into victory.

At the drop of the green flag, Tom Sneva led the early laps, his Phoenix-Cosworth quick but nervous over bumps. Bobby Unser followed close behind, while Rutherford sat patiently in third, his yellow Pennzoil car glued to the line.

By lap 50, Rutherford began his move. The Chaparral’s superior grip allowed him to carry immense cornering speed, running laps faster than anyone even under partial throttle. He passed Sneva cleanly in Turn 1 on lap 58 — a moment of surgical precision that seemed effortless but signaled a new kind of dominance.

From that point on, the race was his.

The Middle Stints

Rutherford and Hall’s team executed pit stops like a synchronized dance — fast, flawless, and calm. Every 30 laps, the car came in for tires and fuel, and each time it rejoined with the lead intact.

By mid-race, Rutherford had lapped nearly the entire field.

Bobby Unser was the only driver remotely capable of staying close, but the Penske struggled with balance on worn tires. Rick Mears, the defending champion, battled gearbox trouble and fell several laps down.

Tom Sneva, ever the risk-taker, tried to keep up by pushing harder into the turns — only to clip the wall exiting Turn 2 on lap 175, ending his charge.

Through it all, Rutherford remained utterly composed. He never over-revved, never deviated from Hall’s data-driven fuel plan, and never put a wheel wrong.

The Final Miles

By the final 20 laps, the crowd understood they were witnessing not just a win, but a demonstration.

The Pennzoil Chaparral 2K — brilliant yellow and perfectly balanced — carved through the closing laps as though it were on rails.

Even when late-race cautions bunched the field, Rutherford maintained total command, accelerating smoothly away on restarts as if the laws of physics simply applied differently to him.

After 3 hours, 29 minutes, and 21 seconds, Johnny Rutherford took the checkered flag to win his third Indianapolis 500 and his first in a ground-effect car.

He led 118 of the 200 laps, and his margin of victory — nearly 30 seconds — was one of the largest of the modern era.

As he coasted to Victory Lane, the yellow car gleaming in the afternoon light, Rutherford waved calmly — a craftsman acknowledging a job perfectly executed.

Aftermath and Legacy

The 1980 Indianapolis 500 marked the beginning of the ground-effect era and the true modernization of Indy racing.

For Johnny Rutherford, it was the pinnacle of his career — his third and final 500 victory, cementing his legacy as one of the smoothest and most technically precise drivers in Speedway history.

For Jim Hall, it was vindication. The Chaparral 2K was revolutionary — the first Indy car built specifically to generate downforce through its underbody tunnels rather than relying solely on wings. Its success triggered an immediate design revolution. Within a year, every major team adopted ground-effect technology, forever changing the architecture of open-wheel racing.

For the Cosworth DFX, the 1980 race reaffirmed its supremacy. Lightweight, responsive, and reliable under sustained boost, it became the universal powerplant — winning 81 consecutive IndyCar races between 1978 and 1986.

And for the Speedway, 1980 was a symbol of order and elegance — a race run without controversy, crashes, or chaos. It was the cleanest, most professional event in years, and it proved that high technology and safety could coexist without compromising competition.

Reflections

The 1980 Indianapolis 500 was not a battle — it was a lesson.

It marked the exact moment when the Indianapolis 500 crossed from mechanical endurance into the aerodynamic age.

Johnny Rutherford and the Chaparral 2K didn’t just win; they changed the physics of how victory was achieved.

It was the perfect expression of late-20th-century racing: calm, calculated, and transcendent in its precision.

As the sun set over the Brickyard that afternoon, the message was clear — the days of brute strength and improvisation were gone. The future belonged to science, symmetry, and those who could master both.

Sources

Indianapolis Motor Speedway Archives — Official Records of the 1980 International 500-Mile Sweepstakes (IMS Heritage Collection)

Motorsport Magazine Archive — “Ground Effect and Golden Glory: The 1980 Indianapolis 500” (May 2080 Centennial Feature)

The Indianapolis Star, May 25–27, 1980 — Race-day coverage and interviews with Rutherford, Hall, and Unser

Automobile Quarterly, Vol. 82, No. 2 (2044) — “The Aerodynamic Revolution: The Chaparral 2K and the New Age of Speed”

Smithsonian Institution — Transportation Collections: Chaparral 2K design data, Cosworth DFX records (1980)