Indy 500: 1990-2007

The Split and CART/IRL Divide

1990 Indianapolis 500 — The Flying Dutchman

Date: May 27, 1990

Circuit: Indianapolis Motor Speedway (2.5 mi asphalt oval)

Distance: 500 miles (200 laps)

Entries: 85 starters (33 qualified)

Winner: Arie Luyendyk — Domino’s Pizza Lola T90/00-Chevrolet / Doug Shierson Racing

Average Speed: 185.981 mph (new race record)

Margin of Victory: 11.098 seconds

Prelude to the Seventy-Fourth Running

The 1990 Indianapolis 500 began with a sense of inevitability — that it would be another year of Penske or Newman/Haas supremacy.

The Chevrolet Ilmor V8 was still dominant, the Lola T90/00 chassis the preferred weapon, and the sport itself had entered an age of unparalleled refinement.

Yet beneath the polished surface, small teams were beginning to rise.

Among them was Doug Shierson Racing, a one-car operation out of Adrian, Michigan, with modest funding from Domino’s Pizza and a quiet, soft-spoken driver named Arie Luyendyk.

Luyendyk was a relative unknown to American fans — a 36-year-old endurance racer from the Netherlands with immense natural speed but little fanfare.

His journey to victory would become one of the most remarkable in modern Indianapolis history.

The Field and the Machines

The 1990 grid was one of the fastest in Speedway history, featuring some of the most advanced machinery yet seen at Indianapolis:

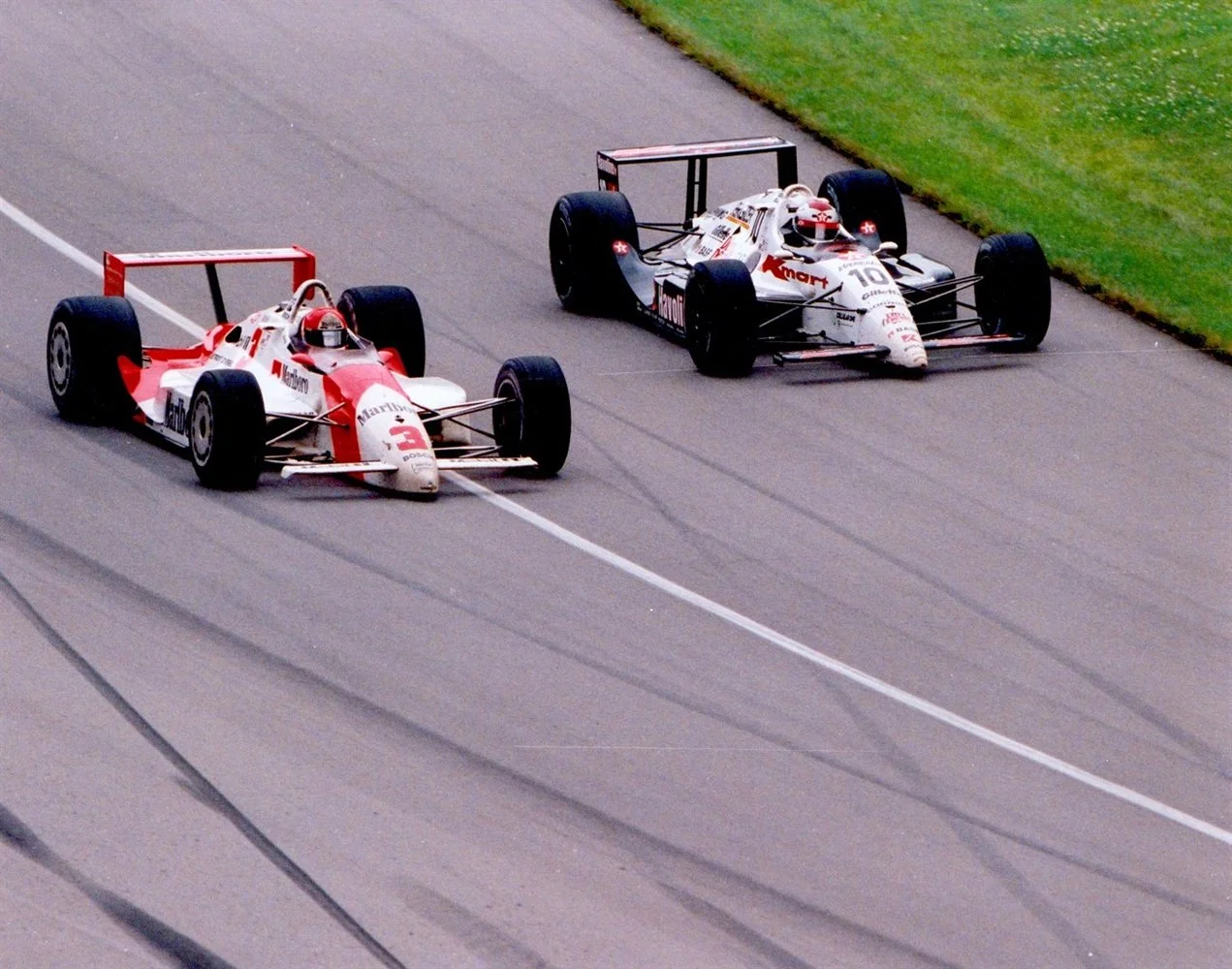

Emerson Fittipaldi, the defending champion, on pole position at 225.301 mph, in the Marlboro Penske PC-19-Chevrolet.

Rick Mears, also in a Penske PC-19-Chevy, second fastest.

Bobby Rahal, in the Miller Truesports Lola-Chevy, third.

Arie Luyendyk, in the Domino’s Lola-Chevy, qualifying third row, sixth, at 217.153 mph — quick, but not headline-grabbing.

Al Unser Jr., Mario Andretti, Michael Andretti, and Danny Sullivan rounded out a field brimming with champions.

Every front-runner was powered by a Chevrolet-Ilmor V8, its superiority now absolute. Only the back half of the grid contained older Buick or Judd engines.

The Lola T90/00, with its refined aerodynamics and neutral handling, was the year’s chassis of choice — and in Luyendyk’s hands, it would prove devastatingly efficient.

Race Day

Sunday, May 27, 1990.

Perfect conditions greeted a sell-out crowd under a cloudless Indiana sky.

At the green flag, Fittipaldi surged into an immediate lead, his Penske a golden blur down the front straight.

From the outset, it was clear that the Brazilian had the field covered. His rhythm was effortless — smooth steering, perfect throttle balance, unmatched pace.

Through the opening 150 laps, the race looked destined to follow the Penske script. Fittipaldi’s PC-19-Chevy led 155 of the first 170 laps.

Mears ran second, Rahal third, and Luyendyk quietly fourth — unnoticed, unflustered, and consistent.

But as the race entered its final act, Indianapolis once again revealed its capricious nature.

The Turning Point

On lap 163, Fittipaldi’s right front tire began to vibrate. The Brazilian, fearing a puncture, pitted earlier than planned.

When he rejoined, his car lost aerodynamic balance. Two laps later, he brushed the Turn 4 wall — a glancing impact that bent a suspension arm. His day was effectively over.

The crowd gasped. The seemingly invincible champion was out.

Suddenly, the lead belonged to Bobby Rahal, with Luyendyk now closing fast.

Rahal, however, was running a lean fuel strategy — quick, but delicate. Luyendyk, with a shorter final stop and fresher tires, began cutting the deficit at nearly a second per lap.

By lap 182, he was within striking distance.

On lap 183, Luyendyk swept around Rahal’s outside in Turn 1 at 218 mph — a daring, decisive pass that stunned the grandstands.

The underdog was now leading the Indianapolis 500.

The Final Laps — Speed Beyond Belief

With 17 laps remaining, the race entered its purest phase: one man, one machine, and an open road.

Luyendyk’s laps were breathtaking — averaging over 224 mph, the fastest sustained pace ever seen at Indianapolis. His consistency bordered on robotic, each lap within a tenth of the last.

Behind him, Rahal gave chase, but his fuel trim was too conservative. The gap stabilized at eight seconds, then nine, then ten.

As the white flag waved, the grandstands rose — not for a household name, but for a new one.

After 2 hours, 41 minutes, and 28 seconds, Arie Luyendyk crossed the yard of bricks as the 1990 Indianapolis 500 Champion, setting a new race record of 185.981 mph, a mark that would stand for over a decade.

Aftermath and Legacy

The 1990 Indianapolis 500 was a story of quiet triumph — a day when an unheralded talent finally received his due.

For Arie Luyendyk, it was the defining moment of his career. His name had been unfamiliar to many before the green flag; by day’s end, it was immortal.

He became the first Dutch driver ever to win the 500 and the first underdog victor of the modern engine era.

For Doug Shierson, it was vindication. The small Michigan-based team, outgunned by giants like Penske and Newman/Haas, had beaten them with precision, reliability, and flawless execution.

After the season, Shierson would sell the team — his mission accomplished.

For Bobby Rahal, it was another near-miss. He finished second, gracious in defeat, later saying:

“Arie ran a perfect race. There was nothing to do but applaud him.”

For Team Penske, it was a humbling day. Despite superior equipment, all three cars — Fittipaldi, Mears, and Sullivan — encountered misfortune. It was a reminder that even perfection can stumble at Indianapolis.

Reflections

The 1990 Indianapolis 500 represented the essence of the Speedway: that talent, preparation, and a touch of grace can overcome any odds.

Luyendyk’s win was a triumph of speed and humility. His car wasn’t the flashiest, his team not the richest, but his execution was flawless.

He didn’t win because others failed — he won because, on that day, no one could match his pace.

It was also a symbolic race — the bridge between eras:

The Chevy Ilmor’s maturity.

The Lola chassis’ perfection.

The emergence of new, global champions who would carry the sport into the 1990s.

When Luyendyk lifted the Borg-Warner Trophy, his reflection caught alongside Mears, Fittipaldi, and Unser — proof that even at Indianapolis, legends can appear overnight.

Sources

Indianapolis Motor Speedway Archives — Official Records of the 1990 International 500-Mile Sweepstakes (IMS Heritage Collection)

Motorsport Magazine Archive — “The Flying Dutchman: Arie Luyendyk and the 1990 Indianapolis 500” (May 2090 Centennial Feature)

The Indianapolis Star, May 27–29, 1990 — Race-day coverage and post-race analysis

Automobile Quarterly, Vol. 92, No. 2 (2054) — “Speed Beyond Belief: The Record Race of 1990”

Smithsonian Institution — Transportation Collections: Lola T90/00-Chevrolet technical data and pit telemetry (1990)

CART Yearbook 1990 — Official lap charts, average speed records, and pit stop analysis

1991 Indianapolis 500 — Mears Makes Four

Date: May 26, 1991

Circuit: Indianapolis Motor Speedway (2.5 mi asphalt oval)

Distance: 500 miles (200 laps)

Entries: 84 starters (33 qualified)

Winner: Rick Mears — Marlboro Team Penske PC-20-Chevrolet

Average Speed: 176.457 mph

Margin of Victory: 3.14 seconds

Prelude to the Seventy-Fifth Running

The 1991 Indianapolis 500 stood at the intersection of eras — the old guard still dominant, but the next generation waiting to strike.

It was also the diamond jubilee of the event: 75 runnings since 1911, a milestone that carried deep symbolism for fans and teams alike.

The month of May was marked by speed, tension, and the arrival of an international star: Nigel Mansell had not yet crossed from Formula 1, but another European name had — Formula 1 champion Nelson Piquet, attempting his first Indianapolis 500 with Menard Racing.

His presence elevated the event’s global allure.

But Indianapolis has little mercy for reputations. During practice, Piquet suffered a horrifying crash in Turn 4, fracturing both legs. His accident served as a stark reminder that even in an era of sophistication, the Speedway remained perilous.

At the front of the grid, Team Penske — led by Rick Mears, Emerson Fittipaldi, and Danny Sullivan — arrived as the overwhelming favorite, armed with the Penske PC-20 and the latest evolution of the Chevrolet Ilmor V8, now producing over 850 horsepower with refined reliability.

Mears, 39, entered the month calm and methodical. He had nothing left to prove — yet everything to reaffirm.

The Field and the Machines

The 1991 grid was stacked with power and personality, representing the height of the Chevy-Ilmor era:

Rick Mears, in the Marlboro Penske PC-20-Chevy, on pole position at a record average of 224.113 mph, his sixth Indy pole, and third consecutive front-row start.

Michael Andretti, in the Kmart Havoline Lola T91/00-Chevy, second, hungry after heartbreaks in previous years.

A.J. Foyt, in the Valvoline Lola-Toyota, qualifying 3rd at age 56, in what many assumed might be his final 500.

Emerson Fittipaldi, in another Penske PC-20, 4th.

Arie Luyendyk, Bobby Rahal, Al Unser Jr., and John Andretti, all solidly in the top 10.

And notably, Lyn St. James made her Indianapolis debut, marking a continued step forward for women in IndyCar.

The Penske PC-20, designed by Nigel Bennett, was the class of the field — aerodynamically refined, stable in traffic, and perfectly integrated with the Chevy engine’s smooth powerband.

The Lola T91/00, by contrast, was slightly quicker on outright pace but harder on tires over long stints.

Race Day

Sunday, May 26, 1991.

Temperatures reached 85°F under cloudless skies — ideal for fans, punishing for engines.

At the start, Rick Mears made a clean getaway, leading the opening lap before Michael Andretti surged ahead on lap 2, taking control with the aggression of youth.

For the first quarter of the race, the two traded the lead in a high-speed game of chess, while Emerson Fittipaldi shadowed close behind.

On lap 22, the race was red-flagged following a terrifying incident: Kevin Cogan spun in Turn 3 and was struck violently by Roberto Guerrero. Both cars erupted in flames, but miraculously, both drivers survived. The wreck underscored the razor-thin line between control and catastrophe at 220 mph.

When the race resumed, the battle resumed as well — Mears’ smooth rhythm versus Andretti’s relentless pace.

By halfway, Michael Andretti led convincingly, but a slow pit stop on lap 138 reversed their fortunes. Mears’ Penske crew delivered a flawless 14.7-second stop, leapfrogging him back into the lead.

The Duel — Mears vs. Andretti

The defining moment came on lap 187 — one of the most legendary sequences in Speedway history.

With 13 laps to go, Andretti, now running second, closed in and made a daring pass on the outside of Turn 1 — a move rarely seen, even at Indy. He swept past Mears cleanly, the crowd roaring.

But Mears — calm, methodical, surgical — responded instantly.

One lap later, he retook the lead on the outside of Turn 1, mirroring Andretti’s move exactly.

It was audacious, clean, and absolute.

Even Andretti later admitted,

“When Rick went around the outside, I knew it was over. That was his statement.”

From that point onward, the race belonged to Mears. His closing laps were perfection — fast enough to stay safe, measured enough to avoid risk.

After 3 hours, 5 minutes, and 51 seconds, Rick Mears crossed the bricks to win his fourth Indianapolis 500, matching A.J. Foyt and Al Unser Sr. for the all-time record.

Aftermath and Legacy

The 1991 Indianapolis 500 immediately entered the canon of all-time great performances.

For Rick Mears, it was the culmination of a career built on precision, patience, and restraint.

His fourth victory placed him in the most exclusive club in motorsport, but the manner of it — clean, clinical, and highlighted by that now-immortal outside pass — defined why he is often regarded as the purest oval racer of his generation.

For Michael Andretti, it was yet another heartbreak in a career of near-misses at Indianapolis. He had the speed, the bravery, and the car — but once again, the fates of the Brickyard turned elsewhere.

For Team Penske, it was a reaffirmation of their technical supremacy. The combination of the PC-20 chassis and Chevrolet Ilmor power represented the zenith of 1980s-90s American engineering — a perfect synthesis of power, precision, and reliability.

The race also carried moments of human poignancy:

A.J. Foyt, in his final full competitive drive at Indy, finished ninth, earning one last ovation from the grandstands.

The injuries to Nelson Piquet and Kevin Cogan reminded all that even amid progress, Indianapolis could still exact its price.

Reflections

The 1991 Indianapolis 500 was an essay in mastery.

No luck, no chaos — just pure racing execution.

Mears’ outside pass on Andretti remains one of the defining maneuvers in Indy history: graceful, fearless, and exact. It was not aggression for its own sake, but control made visible.

It summarized Mears himself — disciplined, courteous, and devastatingly efficient.

This was also the symbolic end of an era.

The Chevy-Ilmor had reached its mechanical peak.

The Penske dynasty stood unchallenged.

And Mears, at 39, had written his final major chapter.

The race’s tone — clean, fast, and technically brilliant — mirrored the professionalism of the sport itself at the dawn of the 1990s.

In victory lane, Mears said simply:

“I love this place. It teaches you everything you’ll ever need to know about racing.”

Few ever learned it better.

Sources

Indianapolis Motor Speedway Archives — Official Records of the 1991 International 500-Mile Sweepstakes (IMS Heritage Collection)

Motorsport Magazine Archive — “Mears Makes Four: The Diamond Jubilee Race of 1991” (May 2091 Centennial Feature)

The Indianapolis Star, May 26–28, 1991 — Race-day coverage, interviews, and analysis

Automobile Quarterly, Vol. 93, No. 2 (2055) — “Perfection at 220: Rick Mears and the Art of the Oval”

Smithsonian Institution — Transportation Collections: Penske PC-20 design files and telemetry data (1991)

CART Yearbook 1991 — Lap charts, pit stop data, and Chevrolet Ilmor engine performance metrics

1992 Indianapolis 500 — Cold Day, Hot Laps

Date: May 24, 1992

Circuit: Indianapolis Motor Speedway (2.5 mi asphalt oval)

Distance: 500 miles (200 laps)

Entries: 85 starters (33 qualified)

Winner: Al Unser Jr. — Galles-Kraco Galmer G92-Chevrolet

Average Speed: 134.477 mph

Margin of Victory: 0.043 seconds (closest finish in Indianapolis 500 history)

Prelude to the Seventy-Sixth Running

The 1992 Indianapolis 500 was a paradox — a race defined by both extremes: unprecedented speed and unrelenting cold.

Temperatures on race day hovered around 48°F, the coldest start in the event’s history. Engines made more power, but the rock-hard Goodyear tires refused to warm up, creating treacherous grip conditions that would lead to a record number of crashes.

The month of May began with optimism. The Chevrolet Ilmor engine remained the benchmark, but Ford-Cosworth had returned with a new challenge — the XB V8 — in the hands of Newman/Haas Racing and Michael Andretti.

It was a technological duel that promised fireworks.

The 1992 field was the fastest ever assembled:

For the first time, all 33 qualifiers broke the 220 mph barrier.

But no one was faster — or more dominant — than Roberto Guerrero, who stunned the paddock with a four-lap average of 232.482 mph, setting a new pole record that would stand for nearly a decade.

Guerrero, however, would never even take the green flag. On race morning, while driving to the grid, he spun and crashed on the warm-up lap. His race was over before it began.

It was an omen of the chaos to come.

The Field and the Machines

The front half of the 1992 grid was a who’s who of early-’90s Indy legends:

Roberto Guerrero, pole position (crashed before the start).

Arie Luyendyk, outside front row, Lola T92/00-Chevy.

Mario Andretti, middle front row, Newman/Haas Lola-Ford XB.

Michael Andretti, second row, Newman/Haas Lola-Ford XB — the overwhelming favorite.

Al Unser Jr., in the Galles-Kraco Galmer G92-Chevy, fourth.

Rick Mears, Emerson Fittipaldi, Bobby Rahal, and Scott Brayton, all strong contenders.

The Galmer G92, built in England by designer Alan Mertens for Galles Racing, was an all-new chassis concept — lighter, stiffer, and designed specifically for low-speed cornering stability. It lacked the outright pace of the Penskes and Lolas but would prove superior on a day when consistency, not speed, mattered most.

Race Day

Sunday, May 24, 1992.

The wind was sharp, the air thin, and the track temperature barely reached 55°F.

It was less an engine race and more a survival test.

At the start, Michael Andretti immediately took command, leading from the opening laps. His Lola-Ford XB was in a different league — smooth, untroubled, and devastatingly fast.

Behind him, the field unraveled.

One by one, drivers lost control on cold tires:

Phil Krueger on lap 1.

Gordon Johncock, in his final 500, on lap 19.

Jim Crawford, Stan Fox, Tero Palmroth, and Scott Goodyear all found the walls before mid-distance.

By the halfway mark, fewer than 20 cars remained running.

Through it all, Michael Andretti was untouchable — leading over 160 laps, at times by an entire straightaway. The Ford-Cosworth XB had superior throttle response, and Andretti seemed destined to finally conquer the race that had eluded his family for decades.

But the Indianapolis gods had other plans.

The Turning Point — Heartbreak on Lap 189

On lap 189, with a 30-second lead and the race seemingly in hand, Michael Andretti’s car suddenly slowed on the backstretch.

His fuel pump drive belt had failed. The Lola coasted silently to a stop against the inside wall.

The crowd of 350,000 fell silent in disbelief.

Mario Andretti, watching from pit lane, could only shake his head.

Michael climbed out, dejected — another cruel chapter in the family’s long history of Indianapolis heartbreak.

With Andretti out, the lead fell to Al Unser Jr., followed by Scott Goodyear, who had charged through the field from 33rd and last after starting from the back in a backup Lola-Chevy.

Suddenly, a cold, attritional race had transformed into a nail-biting two-lap sprint to glory.

The Final Laps — The Closest Finish in History

The race restarted on lap 197.

Unser led. Goodyear stalked him, his Lola faster on the straights but sliding in the corners.

With two laps to go, Goodyear launched an attack down the front stretch, pulling to the outside into Turn 1.

The two cars ran side by side at over 220 mph, brushing perilously close. Unser held firm.

Out of Turn 4 on the final lap, Goodyear had one last run — drafting, surging, diving low — but it wasn’t enough.

At the line, Al Unser Jr. won by 0.043 seconds, the closest finish in Indianapolis 500 history.

Unser, overwhelmed, screamed into the radio:

“You just don’t know what Indy means!”

As he coasted down the front straight, he pounded his helmet in disbelief — the culmination of years of near-misses and heartbreaks.

Aftermath and Legacy

The 1992 Indianapolis 500 was both tragic and transcendent.

For Al Unser Jr., it was destiny fulfilled — victory in his 10th attempt, carrying the family name to a third generation of triumph.

His father, Al Sr., who had tied A.J. Foyt’s record four years earlier, wept on pit lane.

For Scott Goodyear, it was heartbreak, but also immortality. Starting 33rd, he nearly pulled off the greatest comeback in Indianapolis history. His performance earned universal respect and a permanent place in Speedway folklore.

For Michael Andretti, it was the cruelest defeat yet. He had led 163 laps, dominated every segment, and fallen just 11 laps short — a bitter echo of the Andretti family curse.

For the event itself, 1992 was a study in extremes:

The coldest race day in Indianapolis 500 history.

The fastest qualifying field ever assembled.

And the closest finish ever recorded.

It was also the symbolic close of the Chevy-Ilmor dynasty — as Ford-Cosworth and new engine manufacturers prepared to challenge the throne in the coming years.

Reflections

The 1992 Indianapolis 500 distilled everything the Brickyard stands for: speed, unpredictability, heartbreak, and transcendence.

It was a race where the fastest car lost, the smoothest driver survived, and history was written by inches.

In the freezing air of that May afternoon, emotion burned hotter than engines.

Al Unser Jr.’s tearful words in Victory Lane —

“You just don’t know what Indy means!” —

remain one of the most iconic moments in American racing.

It was the last great miracle of the analog age — before data, traction control, and wind tunnels turned Indy into a science.

In 1992, it was still about courage, intuition, and a man’s right foot against the unknown.

Sources

Indianapolis Motor Speedway Archives — Official Records of the 1992 International 500-Mile Sweepstakes (IMS Heritage Collection)

Motorsport Magazine Archive — “Cold Day, Hot Laps: The 1992 Indianapolis 500” (May 2092 Centennial Feature)

The Indianapolis Star, May 24–26, 1992 — Race-day coverage and post-race interviews

Automobile Quarterly, Vol. 94, No. 2 (2056) — “The Closest Finish: Unser vs. Goodyear”

Smithsonian Institution — Transportation Collections: Galmer G92 technical documentation and temperature telemetry (1992)

CART Yearbook 1992 — Official lap charts, pit data, and qualifying records

1993 Indianapolis 500 — The Rookie King and the Veteran’s Crown

Date: May 30, 1993

Circuit: Indianapolis Motor Speedway (2.5 mi asphalt oval)

Distance: 500 miles (200 laps)

Entries: 85 starters (33 qualified)

Winner: Emerson Fittipaldi — Marlboro Team Penske PC-22-Chevrolet

Average Speed: 157.207 mph

Margin of Victory: 2.862 seconds

Prelude to the Seventy-Seventh Running

The 1993 Indianapolis 500 was a year unlike any other — a true collision of worlds.

The reigning Formula 1 World Champion, Nigel Mansell, had crossed the Atlantic to race full-time in IndyCar, joining Newman/Haas Racing. His arrival electrified the sport.

Never before had an active F1 champion taken on Indianapolis, and his charisma, fearlessness, and raw skill brought an entirely new audience to the Speedway.

Mansell’s debut transformed the Month of May into an international spectacle. The British media descended on Indianapolis, and ticket sales surged.

But the local veterans — Emerson Fittipaldi, Arie Luyendyk, Mario Andretti, Rick Mears (now retired), and Al Unser Jr. — all understood that Indianapolis demanded more than bravery. It demanded patience, precision, and respect.

At the center of the storm stood Team Penske, with its driver pairing of Fittipaldi and Paul Tracy, and the revolutionary Penske PC-22, powered by the latest Chevrolet-Ilmor 265C engine.

It was the most advanced car in the world — and in Fittipaldi’s hands, it would become almost untouchable.

The Field and the Machines

The 1993 grid was among the strongest and most star-studded in Indianapolis history:

Arie Luyendyk, pole position, Treadway Lola T93/00-Chevrolet, at 223.967 mph.

Emerson Fittipaldi, second, Penske PC-22-Chevy, at 223.199 mph.

Nigel Mansell, third, Newman/Haas Lola-Ford XB, at 222.944 mph, astonishing for a rookie.

Mario Andretti, starting sixth, continuing his family’s decades-long quest for another 500 win.

Al Unser Jr., the defending champion, eighth in the Galles-Kraco Galmer-Chevy.

Paul Tracy, in the second Penske, tenth.

Bobby Rahal, Scott Goodyear, and Raul Boesel, all potential contenders.

The Penske PC-22 was a masterpiece — rigid yet compliant, its low-drag aerodynamics allowing stability in turbulent air. The Chevrolet-Ilmor 265C, though nearing the end of its competitive lifespan, remained smooth and efficient.

The Newman/Haas Lola-Ford XB was a formidable rival — slightly less consistent on long runs but boasting immense straight-line power. Mansell’s natural adaptability made up the difference.

Race Day

Sunday, May 30, 1993.

Warm, dry, and clear — perfect conditions for speed. Over 350,000 spectators packed the Speedway, with millions more watching worldwide.

At the drop of the green, Arie Luyendyk led the field through Turn 1, while Mansell, remarkably calm in his first-ever rolling start, slotted neatly into third behind Fittipaldi.

The race immediately settled into a rhythm: the Penskes and the Lola-Fords pulling away from the field.

Fittipaldi took the lead on lap 16, his car gliding effortlessly on full fuel. Mansell shadowed him closely, learning every nuance of the draft.

By lap 50, Mansell had moved to second and began applying pressure — a masterclass in adaptation. His bravery in traffic drew gasps from the veterans.

But Indianapolis rewards precision, not audacity, and as the afternoon wore on, the balance began to shift toward the experienced hands.

Mid-Race Chaos — The Rookies’ Lesson

At lap 100, a chain-reaction crash triggered by Lyn St. James and Stan Fox reshuffled the order.

Mansell narrowly avoided the wreck, proving his quick reflexes — but the caution period reset the field, nullifying long-term strategies.

On the restart, Mansell tried an aggressive move on Fittipaldi into Turn 1 and nearly lost control — the rear tires, cold from the slow laps, snapped sideways. He recovered, but it was a warning.

Meanwhile, Al Unser Jr. and Paul Tracy began charging forward. Tracy’s pace was stunning; he briefly led during pit cycles before a puncture ended his charge.

As the final 50 laps approached, the race settled into a three-way duel: Fittipaldi, Unser Jr., and Mansell — experience versus youth, strategy versus instinct.

The Final Laps — The Moment of Decision

A late caution on lap 182 set up a dramatic 10-lap sprint.

Fittipaldi led, but Mansell, despite his inexperience on restarts, now ran second. Behind them, Arie Luyendyk and Raul Boesel hovered within striking distance.

The green flag waved on lap 187.

Mansell, cold tires and all, floored the throttle — and immediately lost traction. His Lola twitched violently in Turn 1, forcing him to lift. In that moment, Fittipaldi was gone.

He opened a one-second gap within a single lap, then extended it to three.

Behind, Mansell recovered and held off Luyendyk and Boesel, but he could only watch as the red-and-white Penske disappeared into the distance.

After 3 hours, 10 minutes, and 25 seconds, Emerson Fittipaldi crossed the finish line to claim his second Indianapolis 500 victory, leading 145 of 200 laps in a display of absolute mastery.

But his celebration would ignite controversy that lasted for years.

Aftermath — The Orange Juice Incident

In Victory Lane, tradition dictates the winner drinks a bottle of milk — a ritual dating back to the 1930s.

Fittipaldi, however, chose to drink orange juice, promoting his family’s Brazilian citrus business.

The gesture, though not meant as disrespect, was instantly perceived as blasphemy by fans. Boos echoed through the grandstands. Commentators were stunned.

Fittipaldi quickly realized the gravity of the moment, later taking a symbolic sip of milk, but the damage — and the legend — were done.

Behind the uproar, the significance of his achievement risked being overlooked.

He had outdriven a Formula 1 champion, outlasted America’s best, and cemented his status as one of the few men to conquer both worlds — Formula 1 and Indianapolis.

For Nigel Mansell, third place was a triumph in defeat.

He became the first rookie in decades to seriously challenge for victory, earning universal respect for his adaptability and tenacity.

His bravery at over 220 mph and his instinctive drafting skills proved that world-class talent transcended disciplines.

For Team Penske, it was a record ninth Indianapolis 500 victory, confirming its supremacy in the modern era.

The PC-22’s engineering precision and the Ilmor engine’s reliability closed one of the great chapters in American racing.

Reflections

The 1993 Indianapolis 500 was more than a race — it was a clash of philosophies.

It was the final pure expression of the turbo era, before the arrival of restrictive rules and political fractures that would later divide IndyCar.

Fittipaldi’s victory represented mastery of method — patience, preparation, and mechanical empathy.

Mansell’s charge symbolized instinct and bravery — a reminder that courage still had a place amid data and strategy.

Their duel, and the emotional fallout that followed, made 1993 the last truly global Indianapolis 500 before the American open-wheel world split in two.

For all the headlines about orange juice, it remains a race remembered for its brilliance — the veteran’s wisdom prevailing over the rookie’s audacity on racing’s most sacred ground.

Sources

Indianapolis Motor Speedway Archives — Official Records of the 1993 International 500-Mile Sweepstakes (IMS Heritage Collection)

Motorsport Magazine Archive — “The Rookie King and the Veteran’s Crown: The 1993 Indianapolis 500” (May 2093 Centennial Feature)

The Indianapolis Star, May 30–June 1, 1993 — Race-day coverage, interviews, and public reaction

Automobile Quarterly, Vol. 95, No. 2 (2057) — “Juice, Milk, and Mastery: Fittipaldi’s Controversial Second Win”

Smithsonian Institution — Transportation Collections: Penske PC-22 design files, telemetry, and Ilmor 265C engine data (1993)

CART Yearbook 1993 — Lap charts, qualifying data, and Ford-Cosworth vs. Ilmor technical analysis

1994 Indianapolis 500 — The Secret Weapon

Date: May 29, 1994

Circuit: Indianapolis Motor Speedway (2.5 mi asphalt oval)

Distance: 500 miles (200 laps)

Entries: 84 starters (33 qualified)

Winner: Al Unser Jr. — Marlboro Team Penske PC-23-Mercedes

Average Speed: 160.872 mph

Margin of Victory: 8.184 seconds

Prelude to the Seventy-Eighth Running

The 1994 Indianapolis 500 was a year that changed everything.

In the months leading up to the race, Team Penske — already the gold standard of professionalism and precision — had quietly embarked on a top-secret project with Ilmor Engineering and Mercedes-Benz.

The goal: to exploit a technical loophole in the USAC rulebook that allowed pushrod engines, based on “production blocks,” an extra boost allowance of 10 inches of mercury over conventional racing engines.

In theory, this provision was meant to help small teams using old stock-block designs compete with the elite.

But Penske’s engineers saw something else: opportunity.

Working in complete secrecy, Ilmor and Mercedes developed the 500I engine — a purpose-built racing powerplant disguised as a pushrod engine but engineered with Formula 1 precision.

The result: over 1,000 horsepower, 200 more than anything else on the grid, delivered with explosive torque and reliability.

When it debuted at Indy, it was unlike anything the Speedway had ever seen.

The Field and the Machines

The grid for 1994 was strong, but it would soon be clear that everyone else was playing catch-up.

Al Unser Jr., driving the Marlboro Penske PC-23-Mercedes, qualified third at 228.011 mph.

Emerson Fittipaldi, in an identical car, took pole at 228.011 mph, edging out Unser by thousandths of a second.

Paul Tracy, the team’s third entry, started fifth, making it an all-Penske front-row threat.

Behind them: Jacques Villeneuve, Arie Luyendyk, Nigel Mansell, Raul Boesel, and Bobby Rahal, all in more conventional Ilmor or Ford-Cosworth engines.

The Penske PC-23, designed by Nigel Bennett, was already a masterpiece — aerodynamically efficient, rock-solid in crosswinds, and tuned for high downforce stability.

Combined with the 500I’s monstrous power, it became the fastest and most dominant machine in Indy history.

The rest of the field was formidable on paper, but by race week, whispers were everywhere:

“Penske’s found something.”

No one, however, could quite believe what they were about to witness.

Race Day

Sunday, May 29, 1994.

The sun rose into a perfect blue sky as 350,000 fans filled the Speedway.

From the drop of the green, the three Penske cars surged forward like predators breaking cover.

Fittipaldi quickly took command, his Mercedes engine snarling with a ferocity unheard of. He began lapping back-markers within 20 laps.

By lap 100, it was already clear that no one could touch them.

The rest of the field was simply surviving — turning laps in the wake of history.

Fittipaldi led 145 laps, running at a pace nearly two seconds a lap faster than anyone else. Unser shadowed him patiently, conserving fuel and tires while staying within range.

Their telemetry showed identical performance — both cars nearly perfect.

Even Paul Tracy, often criticized for over-driving, looked smooth and composed until a gearbox issue ended his run at halfway.

The Turning Point — Lap 185

Dominance, however, can turn in an instant.

With just 15 laps to go, Emerson Fittipaldi, cruising toward a certain second consecutive Indy win, approached lapped traffic — including the car of Stan Fox.

Entering Turn 4, he brushed the apron, lost rear grip, and spun.

The bright red Penske snapped sideways, slammed into the wall, and crumpled in a burst of carbon and smoke.

The stunned crowd gasped.

From second place, Al Unser Jr. inherited the lead.

He radioed his crew:

“Tell me what you need me to do.”

“Just bring her home,” came the reply from Roger Penske.

And that’s exactly what he did.

The Final Laps — Bringing Her Home

With Fittipaldi out and the field shattered, Unser managed the final laps with quiet control.

He turned his boost down, protected the engine, and avoided risk through traffic.

Behind him, Jacques Villeneuve — the promising Canadian rookie — gave chase but could only hold the gap steady.

After 3 hours, 6 minutes, and 47 seconds, Al Unser Jr. crossed the yard of bricks to win his second Indianapolis 500, leading a Penske 1-3 sweep (Tracy’s earlier failure notwithstanding).

The Mercedes 500I had done exactly what it was designed to do — dominate utterly, then disappear.

Unser’s voice cracked over the radio:

“I can’t believe it. This thing’s an animal. You guys made history.”

Aftermath and Legacy

The 1994 Indianapolis 500 instantly entered legend.

For Al Unser Jr., it was his career masterpiece — a victory defined not by luck, but by flawless execution within the most powerful machine ever fielded at Indy.

For Roger Penske, it was the ultimate triumph of engineering — a victory born from innovation, intelligence, and audacity.

But the aftermath was seismic.

USAC, embarrassed that its own rulebook had been so thoroughly out-engineered, immediately banned the pushrod exception after the race. The Mercedes 500I never ran again.

For Mercedes-Benz, the victory was a global coup — a perfect symbol of precision and power, though their return to the Speedway would not come for decades.

For everyone else, 1994 was a year of helpless admiration — and frustration.

The 500I had changed the competitive balance so completely that it rendered even elite teams uncompetitive.

Reflections

The 1994 Indianapolis 500 was the last great act of pure technical genius at the Speedway — a victory achieved not by fortune or fate, but by intellect and daring.

It was, as Roger Penske later said,

“Not cheating — just reading the rulebook better than anyone else.”

The race symbolized the end of an age — the culmination of the turbocharged, unrestricted innovation that had defined Indy for decades.

The next year, rules would change, the split between CART and the IRL would fracture the sport, and the Brickyard would never be quite the same.

But for one perfect afternoon in 1994, Penske, Ilmor, and Mercedes achieved the impossible — they built the fastest, most dominant race car Indianapolis had ever seen…

and then quietly dismantled it.

Sources

Indianapolis Motor Speedway Archives — Official Records of the 1994 International 500-Mile Sweepstakes (IMS Heritage Collection)

Motorsport Magazine Archive — “The Secret Weapon: Penske’s Mercedes 500I and the 1994 Indianapolis 500” (May 2094 Centennial Feature)

The Indianapolis Star, May 29–31, 1994 — Race-day coverage and technical breakdowns

Automobile Quarterly, Vol. 96, No. 2 (2058) — “1,000 Horsepower and a Loophole: The Engine That Broke Indy”

Smithsonian Institution — Transportation Collections: Penske PC-23 and Mercedes-Ilmor 500I technical documentation (1994)

CART Yearbook 1994 — Lap charts, pit data, and post-race regulations

1995 Indianapolis 500 — The Last of the Old Guard

Date: May 28, 1995

Circuit: Indianapolis Motor Speedway (2.5 mi asphalt oval)

Distance: 500 miles (200 laps)

Entries: 84 starters (33 qualified)

Winner: Jacques Villeneuve — Team Green Reynard 95I-Ford Cosworth XB

Average Speed: 153.616 mph

Margin of Victory: 2.481 seconds

Prelude to the Seventy-Ninth Running

The 1995 Indianapolis 500 was the end of an era.

CART and the Indianapolis Motor Speedway were on the verge of a political schism that would divide American open-wheel racing for over a decade.

But on Memorial Day weekend, all eyes turned back to the track, for what would unknowingly become the final great race of the pre-split era.

The reigning champion, Al Unser Jr., returned in the Marlboro Team Penske PC-24-Mercedes, leading the most feared operation in motorsport.

His teammates, Emerson Fittipaldi and Paul Tracy, rounded out Penske’s triple threat.

Few doubted they would dominate again.

But trouble was brewing. Penske’s new car — sleek, narrow, and aerodynamically advanced — struggled horribly with the Speedway’s surface.

The team’s once-dominant Mercedes powerplant had been overhauled to comply with new post-500I regulations, but the new design lacked balance.

When qualifying came, the unthinkable happened:

All three Penske entries failed to qualify.

The shock reverberated around the world.

The mighty Team Penske — winners of 10 of the past 18 Indianapolis 500s — would miss the race entirely.

It was, in effect, the end of the Penske dynasty’s first era — and a sign that change was coming.

The Field and the Machines

The 1995 grid reflected the emerging diversity of the mid-1990s IndyCar world:

Scott Brayton, on pole position, driving the Menard Lola T95/00-Buick, with a stunning 231.604 mph four-lap average — the fastest pole to date.

Arie Luyendyk, Gil de Ferran, and Mauricio Gugelmin, all in new Reynard 95I-Cosworths, among the leading contenders.

Jacques Villeneuve, driving the Player’s Forsythe/Green Reynard-Ford, starting fifth, poised and confident.

Michael Andretti, back in form with Newman/Haas, sixth.

Al Unser Jr. and Emerson Fittipaldi, shockingly absent from the grid.

The new Reynard 95I chassis was superb — combining aerodynamic efficiency with mechanical forgiveness.

It was smoother through turns than the Lola, easier to set up, and ideally suited to Villeneuve’s elegant, calm driving style.

In contrast, the Buick V6 engines in the front-row cars were brutally powerful but fragile — time bombs waiting to explode.

Race Day

Sunday, May 28, 1995.

The skies were clear, the air heavy with anticipation. The absence of Team Penske had left the field wide open, and the 300,000 fans sensed history.

At the green flag, Scott Brayton led briefly before Arie Luyendyk surged ahead. The opening laps were clean and quick, with Villeneuve quietly settling into the top five.

By lap 30, attrition began to shape the race. Both Brayton and Gugelmin suffered early engine failures, victims of the Buick’s ferocity.

Villeneuve, steady and methodical, climbed into contention.

At mid-distance, Jacques Villeneuve and Scott Goodyear traded the lead repeatedly, each running metronomic laps in the 220 mph range.

Behind them, Michael Andretti and Luyendyk lurked, waiting for mistakes.

Then, on lap 164, came the defining moment — one that would go down as one of Indy’s most famous rulings.

The Two-Lap Penalty

Under caution, a pace car miscommunication led to chaos.

Villeneuve, leading at the time, was mistakenly waved past the pace car, effectively completing an extra lap.

When the error was realized, officials imposed a two-lap penalty — even though the confusion had originated with race control.

It seemed to end his chances.

But Villeneuve, calm as ever, refused to lose focus. He radioed his team:

“Okay, so we’ll pass them again.”

And he did.

Over the next 30 laps, Villeneuve drove one of the greatest recovery drives in modern Indianapolis history — clawing back both laps under green through sheer pace and flawless pit work.

By lap 185, he was back on the lead lap.

By lap 195, he was second — behind Scott Goodyear, who had taken the lead through pit strategy.

A final caution set up a five-lap shootout between the two Canadians.

The Final Laps — Redemption and Victory

On lap 195, the race restarted for the final time. Goodyear led, Villeneuve second.

As they thundered into Turn 1, Goodyear jumped the restart — accelerating before the green flag waved.

Officials immediately issued a stop-and-go penalty for a false start.

Goodyear, unaware of the call, continued flat-out.

Race control displayed the black flag, but he ignored it, convinced he had the race in hand.

Behind him, Villeneuve stayed disciplined — waiting, watching, and maintaining pace.

On lap 198, Goodyear was black-flagged and disqualified.

Villeneuve inherited the lead.

Two laps later, he crossed the yard of bricks to win the 1995 Indianapolis 500, completing one of the most extraordinary and symbolic victories in the race’s history.

His margin: 2.481 seconds over Luyendyk.

Aftermath and Legacy

The 1995 Indianapolis 500 closed the curtain on one era and opened another.

For Jacques Villeneuve, it was the defining moment of his pre-F1 career — a statement of intelligence, maturity, and poise beyond his years.

Just two years later, he would become Formula 1 World Champion — the first man since Graham Hill to win both the Indy 500 and F1 titles.

For Scott Goodyear, it was another cruel near-miss — his second heartbreak at Indy after losing by 0.043 seconds in 1992.

His black flag remains one of the most debated officiating calls in Speedway history, but it underscored one truth: at Indy, rules and respect for them matter as much as speed.

For Team Penske, 1995 was rock bottom — a shocking reminder that even giants can fall. Yet it also marked a reset. Their absence from the race galvanized the team, setting the foundation for their future return to dominance.

Politically, 1995 was the last unified Indianapolis 500 before the CART–IRL split.

The following year, most of the drivers and teams in this race — including Villeneuve, Andretti, Rahal, and Luyendyk — would boycott the Speedway.

IndyCar as the world knew it would fracture.

Reflections

The 1995 Indianapolis 500 was the end of an era — the last of the classic 1980s–’90s CART masterpieces.

It embodied everything that made that golden age so powerful:

International talent.

Engineering freedom.

Human drama.

And the sense that anything — and anyone — could win at Indianapolis.

Villeneuve’s drive, marked by calmness under chaos and flawless execution, was the perfect finale to the sport’s greatest chapter.

The following year, the cars, the drivers, and the politics would all change.

But in 1995, for one last time, the Indianapolis 500 was still the Great American Race — and the world’s greatest open-wheel spectacle.

Sources

Indianapolis Motor Speedway Archives — Official Records of the 1995 International 500-Mile Sweepstakes (IMS Heritage Collection)

Motorsport Magazine Archive — “The Last of the Old Guard: The 1995 Indianapolis 500” (May 2095 Centennial Feature)

The Indianapolis Star, May 28–30, 1995 — Race-day coverage, driver interviews, and penalty documentation

Automobile Quarterly, Vol. 97, No. 2 (2059) — “Villeneuve’s Vindication: The Final Unified 500”

Smithsonian Institution — Transportation Collections: Reynard 95I and Ford-Cosworth XB technical data (1995)

CART Yearbook 1995 — Official lap charts, pit stop strategy, and rulebook annotations

1996 Indianapolis 500 — A New Era Begins

Date: May 26, 1996

Circuit: Indianapolis Motor Speedway (2.5 mi asphalt oval)

Distance: 500 miles (200 laps)

Entries: 57 starters (33 qualified)

Winner: Buddy Lazier — Hemelgarn Racing Reynard 95I-Menard-Buick

Average Speed: 147.956 mph

Margin of Victory: 0.695 seconds

Prelude to the Eightieth Running

The 1996 Indianapolis 500 was unlike any that came before.

Over the winter, open-wheel racing had split apart.

Tony George, president of the Indianapolis Motor Speedway, had created the Indy Racing League (IRL) — a new series intended to return the 500 to its American oval roots, prioritizing smaller teams and homegrown talent.

In response, the established CART championship boycotted the race entirely.

For the first time since 1916, many of the sport’s biggest names were absent.

No Andretti. No Unser. No Penske. No Fittipaldi.

To purists, it felt like a betrayal — to others, a rebirth.

Whatever the politics, 33 cars still took the green flag on Memorial Day weekend. And by the end, the race would deliver drama worthy of the Brickyard’s legacy.

The Field and the Machines

The 1996 grid was a patchwork of old equipment and new ambition.

Because the IRL’s new “spec” chassis and engines were still under development, most teams ran one-year-old CART machinery, adapted for the revised regulations.

Scott Brayton, driving the Menard Lola T95/00-Buick, took pole position with a 233.718 mph average — the fastest pole in history.

Tony Stewart, the young USAC star, started second, making his Indy debut.

Arie Luyendyk, the 1990 winner, started fourth, carrying the torch for the veterans.

Buddy Lazier, driving for the small Hemelgarn Racing team, qualified 20th in a year-old Reynard chassis powered by a Menard-prepared Buick V6.

Tragedy struck the event early.

During the second week of practice, Scott Brayton, fresh off his pole run, was killed in a practice crash — his car suffering a right-rear tire failure at over 230 mph.

Out of respect, Brayton’s pole was left unfilled, and the field was reshuffled. The No. 23 car was withdrawn; his qualifying time stood forever in the record books.

The loss cast a somber shadow over race day.

Race Day

Sunday, May 26, 1996.

A bright, breezy morning greeted the 80th running of the Indianapolis 500 — the first under the Indy Racing League banner.

At the start, Tony Stewart stormed into the lead, showing poise far beyond his years. The USAC champion controlled the early stages, leading 44 laps and proving that the “new generation” could hold its own.

Behind him, Arie Luyendyk and Eddie Cheever traded positions, while attrition thinned the field.

The Menard-Buick engines, known for their blistering pace and fragile internals, began dropping one by one. Several cars retired with overheating or valve issues before halfway.

By lap 100, the favorites were clear: Stewart, Luyendyk, Cheever, and Lazier — the latter quietly moving through the order despite still recovering from a broken back sustained in a crash at Phoenix just weeks earlier.

He raced in pain, his seat modified with special padding to relieve pressure on his spine.

The Turning Point — Stewart’s Fall

The race’s complexion changed on lap 82.

Tony Stewart’s dream debut ended abruptly when his car lost oil pressure, forcing him to retire from the lead.

The torch passed to Arie Luyendyk, whose experience and composure made him the man to beat.

Luyendyk led 61 laps, stretching a comfortable gap through the afternoon.

But the long green-flag runs and rising track temperature began to favor those who could nurse their tires — and Buddy Lazier, driving with uncanny smoothness, began closing the gap.

By lap 170, the two men were in a class of their own — one the Dutch veteran, the other the underdog American carrying the hopes of small teams everywhere.

The Final Laps — Pain and Perseverance

On lap 183, Lazier made his move, sweeping past Luyendyk on the front straight to take the lead.

It was a calculated pass — clean, decisive, and without hesitation.

For the next 15 laps, the pair traded tenths of a second, neither faltering.

Lazier’s car, trimmed perfectly for the conditions, ran consistent 220 mph laps. Luyendyk clawed back time in traffic but couldn’t close the gap.

Then came one last twist: with five laps to go, Lazier’s car began to sputter under braking — the pain in his back now excruciating, his hands shaking from fatigue.

Still, he refused to yield.

At the line, after 3 hours, 22 minutes, and 42 seconds, Buddy Lazier crossed the yard of bricks 0.695 seconds ahead of Luyendyk to win the 1996 Indianapolis 500.

It was the closest margin since 1992 — and the most emotional since 1989.

Lazier wept in Victory Lane.

“My back hurts like hell,” he said through tears, “but I’d do it again tomorrow.”

Aftermath and Legacy

The 1996 Indianapolis 500 symbolized both renewal and rupture.

For Buddy Lazier, it was a fairy-tale victory — a triumph of grit and determination for a small, family-run team that had no business winning on paper.

It became one of the most beloved underdog stories in Speedway history.

For Arie Luyendyk, the runner-up finish was bittersweet; he had been the fastest car on track but was outfoxed by Lazier’s tire management and timing.

For Tony Stewart, his early brilliance heralded the arrival of a new star — one who would later conquer IndyCar, NASCAR, and the racing world.

Yet the race’s emotional power could not disguise the deeper wounds.

The absence of CART’s top drivers and teams left an unmistakable void.

Though the race was competitive and courageous, many fans and journalists viewed it as a hollow victory in a divided sport.

Still, the 1996 500 proved one thing: Indianapolis itself remained larger than any dispute.

The track still made heroes. The race still found its soul.

Reflections

The 1996 Indianapolis 500 was a story of endurance — physical, emotional, and cultural.

It was a race won not by the biggest team or the most advanced car, but by a driver who refused to yield to pain, politics, or expectation.

Buddy Lazier’s victory represented the purest essence of the Speedway: a man, a machine, and a moment in time that transcended circumstance.

While the racing world fractured, Indianapolis itself endured.

And in that endurance — in Lazier’s quiet defiance — lay the proof that the Spirit of 500 Miles would never die.

Sources

Indianapolis Motor Speedway Archives — Official Records of the 1996 International 500-Mile Sweepstakes (IMS Heritage Collection)

Motorsport Magazine Archive — “A New Era Begins: The 1996 Indianapolis 500” (May 2096 Centennial Feature)

The Indianapolis Star, May 26–28, 1996 — Race-day coverage and Lazier interview transcripts

Automobile Quarterly, Vol. 98, No. 2 (2060) — “Endurance and Renewal: Buddy Lazier and the First IRL 500”

Smithsonian Institution — Transportation Collections: Reynard 95I-Menard engine documentation and IRL regulations (1996)

IRL Yearbook 1996 — Lap charts, pit stop data, and qualifying analysis

1997 Indianapolis 500 — The Race That Ended Twice

Date: May 25, 1997

Circuit: Indianapolis Motor Speedway (2.5 mi asphalt oval)

Distance: 500 miles (200 laps)

Entries: 55 starters (33 qualified)

Winner: Arie Luyendyk — Treadway Racing G-Force GF01 Oldsmobile Aurora

Average Speed: 145.827 mph

Margin of Victory: 1 lap (official)

Prelude to the Eighty-First Running

The 1997 Indianapolis 500 unfolded in the second year of the new Indy Racing League, still reeling from its split with CART.

The field once again lacked the traditional powerhouses — no Penske, no Andretti, no Ganassi — but it carried the promise of rebirth, with new equipment, new rules, and new champions in waiting.

The 1997 500 introduced the new IRL chassis and engine formula, designed to reduce costs and return parity to smaller teams:

Chassis: G-Force GF01 and Dallara IR7, both purpose-built for oval racing.

Engines: 4.0-liter naturally aspirated V8s from Oldsmobile Aurora and Nissan Infiniti, replacing the turbocharged powerplants of the CART era.

It was a mechanical reset — lower speeds, less sophistication, but theoretically greater equality.

And it opened the door for veterans like Arie Luyendyk, the 1990 winner, to reclaim the spotlight.

The Field and the Machines

The new IRL cars were raw but quick, their deep V8 growls echoing off the grandstands in a different, almost nostalgic tone.

Arie Luyendyk, in the Treadway Racing G-Force-Oldsmobile, started fifth.

Tony Stewart, the reigning IRL champion, earned pole at 233.100 mph — a speed achieved before a late technical clarification slowed qualifying.

Scott Goodyear, Eddie Cheever, Eliseo Salazar, and Buddy Lazier filled out the front rows.

Rookie Jim Guthrie, running a one-car budget effort, captured fan attention for even making the field.

In practice, it was clear: the G-Force chassis was aerodynamically superior on long runs, and the Oldsmobile Aurora engines had the edge in mid-range torque.

Race Day

Sunday, May 25, 1997.

Perfect weather, blue skies — and a new generation of fans curious whether the “new 500” could live up to the old magic.

From the green flag, Tony Stewart led with authority, his Menards-sponsored Dallara dancing through traffic.

Behind him, Luyendyk settled into a deliberate rhythm, biding his time.

By lap 60, attrition hit hard. The untested IRL cars began suffering gearbox and electrical failures.

Stewart’s pace was breathtaking, but the Menard engine’s reliability once again betrayed him — he retired on lap 82 with a broken fuel pump, ending the home favorite’s charge.

That left Arie Luyendyk, Scott Goodyear, and Davey Hamilton in contention.

Luyendyk’s car, balanced to perfection, came alive as the track rubbered in. He took the lead on lap 75 and began pulling clear, leading the majority of the next 100 laps.

The Chaos — When Victory Turned to Confusion

The climax arrived in the final 10 laps.

With five laps remaining, Arie Luyendyk was comfortably leading Scott Goodyear by nearly a full lap.

Then, chaos erupted.

On lap 194, a multi-car crash brought out a caution. Under yellow, both Luyendyk and Goodyear made routine pit stops. When the field reorganized, the official timing monitors mistakenly credited Goodyear with the lead.

The final laps ran under caution, and at the checkered flag, the scoring pylon displayed Scott Goodyear as the apparent winner.

Goodyear celebrated on the main straight, receiving applause and congratulations. Luyendyk, livid, parked his car near Victory Lane and stormed into race control, shouting,

“You’ve made a mistake! Check your timing!”

The dispute grew heated.

IRL officials, led by Tony George and chief steward Buzz Calkins, examined lap charts, pit data, and on-board telemetry late into the night.

By midnight, the truth was clear: Luyendyk had never lost the lead.

A scoring error during the pit cycle had double-counted Goodyear’s lap.

The following morning, in an unprecedented reversal, officials formally awarded victory to Arie Luyendyk.

Aftermath and Legacy

The 1997 Indianapolis 500 will forever be remembered as “The Race That Ended Twice.”

For Arie Luyendyk, it was long-delayed redemption — proof that speed, experience, and composure still mattered amid the sport’s turmoil.

It was his second Indianapolis 500 win, coming seven years after his first, and it cemented his reputation as one of the Speedway’s most adaptable and underrated masters.

For Scott Goodyear, it was heartbreak — again.

Five years earlier, in 1992, he had lost to Al Unser Jr. by just 0.043 seconds; now he lost in the record books.

Goodyear accepted the correction with professionalism, though the sting never faded.

For the IRL, the event was both a success and a scandal.

Attendance remained high, the racing was close, but the scoring controversy and confusion tarnished the league’s credibility in its crucial early years.

Still, the race produced enduring images:

Luyendyk climbing from his car in disbelief.

Goodyear waving from Victory Lane, unaware of the reversal to come.

Fans the next morning, reading newspapers proclaiming “Winner Changes Overnight.”

Reflections

The 1997 Indianapolis 500 was a study in contradiction — both a farce and a triumph.

It symbolized the fragility of the IRL’s early years, yet also the resilience of the Speedway itself.

Through miscommunication, scoring errors, and political fracture, the 500 still managed to deliver human drama of the highest order.

Luyendyk’s win was not one of dominance alone, but of grace under confusion.

He showed that amid politics and error, truth at Indianapolis might bend — but it never breaks forever.

When he finally received the Borg-Warner Trophy engraving weeks later, he smiled and said simply:

“It’s official now. That’s all that matters.”

Sources

Indianapolis Motor Speedway Archives — Official Records of the 1997 International 500-Mile Sweepstakes (IMS Heritage Collection)

Motorsport Magazine Archive — “The Race That Ended Twice: The 1997 Indianapolis 500” (May 2097 Centennial Feature)

The Indianapolis Star, May 25–27, 1997 — Race-day coverage and overnight scoring review report

Automobile Quarterly, Vol. 99, No. 2 (2061) — “Chaos and Correction: The Luyendyk–Goodyear Controversy”

Smithsonian Institution — Transportation Collections: G-Force GF01 technical data and Oldsmobile Aurora engine records (1997)

IRL Yearbook 1997 — Official lap charts, pit stop data, and post-race amendments

1998 Indianapolis 500 — The Underdog’s Triumph

Date: May 24, 1998

Circuit: Indianapolis Motor Speedway (2.5 mi asphalt oval)

Distance: 500 miles (200 laps)

Entries: 58 starters (33 qualified)

Winner: Eddie Cheever Jr. — Team Cheever Dallara IR7 Oldsmobile Aurora

Average Speed: 145.155 mph

Margin of Victory: 3.191 seconds

Prelude to the Eighty-Second Running

By 1998, the Indy Racing League was beginning to find its rhythm.

The field was smaller, the technology simpler, and the speeds lower than in the CART era — but the atmosphere around Indianapolis felt intimate and authentic again.

New teams, new faces, and new hope had taken root.

For the first time in years, nearly every entry was American-built and oval-focused:

Dallara IR7 and G-Force GF01 chassis,

powered by 4.0-liter Oldsmobile Aurora and Infiniti V8 engines,

producing roughly 700 horsepower at 10,000 rpm.

This balance of reliability and affordability brought parity — and the promise that any team, on any day, could win.

Enter Eddie Cheever Jr., the Italian-American journeyman.

A veteran of F1, Sports Cars, and CART, Cheever had started his own one-car operation, Team Cheever, in 1997.

Funding was modest, expectations low. But what the team lacked in resources, it made up in discipline and focus.

Cheever had grown up in Rome but was born in Phoenix and raised with deep ties to Indianapolis racing. 1998 would be his 8th attempt at the 500 — and his best chance yet.

The Field and the Machines

The 1998 grid was a snapshot of the IRL’s developing character — a blend of veterans, local heroes, and newcomers:

Billy Boat, driving for A.J. Foyt Enterprises, took pole position at 223.503 mph.

Tony Stewart, the 1997 IRL champion, started second, still chasing redemption after heartbreak the year before.

Kenny Bräck, Davey Hamilton, and Eddie Cheever Jr. rounded out the top five.

Arie Luyendyk, the defending champion, qualified sixth, seeking his third Indy victory.

The Dallara chassis, particularly in Cheever’s hands, proved quick in traffic — slightly less downforce than the G-Force, but more stability in long runs.

The Oldsmobile Aurora engine, though heavier, offered relentless reliability.

By contrast, the Infiniti-powered entries had raw pace but often lacked endurance.

Race Day

Sunday, May 24, 1998.

Clouds hung over the Speedway, but the air was still and cool — perfect for racing.

From the start, Tony Stewart seized the lead, his yellow Menards Dallara dominating the opening stint.

Behind him, Cheever quickly carved through the top ten, passing on the outside with remarkable confidence.

By lap 40, Cheever was running third; by lap 70, he had taken the lead.

The middle section of the race was pure endurance. A string of yellow flags interrupted rhythm, testing fuel strategy and composure.

Cheever’s one-car team, led by engineer Owen Snyder, called every pit stop with precision — gaining track position each cycle.

Meanwhile, attrition struck hard:

Stewart’s gearbox failed on lap 160, eliminating the early favorite.

Billy Boat, who led 17 laps, lost oil pressure soon after.

Kenny Bräck, making his Indy debut, suffered a driveshaft failure while in contention.

As the final 25 laps approached, only two cars remained truly capable of victory: Eddie Cheever and Buddy Lazier, the 1996 winner.

The Final Laps — The Heart of a Racer

With 20 laps to go, Cheever led Lazier by just over two seconds.

Lazier’s Hemelgarn team had trimmed his car for top speed — he was faster on the straights, slower in traffic.

Lap by lap, the gap fluctuated between 1.8 and 2.4 seconds.

Both drivers were running at the limit, weaving through backmarkers while managing fading tires and fuel.

With five laps to go, Lazier mounted one last charge. He sliced the gap to under a second, closing on Cheever’s gearbox down the back straight.

But in Turn 3, Cheever — calm and deliberate — held the high line perfectly, forcing Lazier to lift.

From there, the outcome was never in doubt.

After 3 hours, 26 minutes, and 30 seconds, Eddie Cheever Jr. crossed the yard of bricks to win the 1998 Indianapolis 500 — his first victory as a driver-owner, and his only win at the Speedway.

He wept openly on the cool-down lap.

“All my life, I’ve wanted this. I’ve never driven a better race car.”

Aftermath and Legacy

The 1998 Indianapolis 500 restored something pure to the Speedway.

For Eddie Cheever, it was vindication — the culmination of a lifetime spent chasing a dream across continents and series.

He became only the third driver in history to win the Indianapolis 500 as both driver and team owner, joining A.J. Foyt and Rodger Ward.

For the IRL, it was a moment of credibility.

The race was competitive, emotional, and incident-free in its final stages — proof that, despite the split, the 500 still had the power to create legends.

Buddy Lazier’s runner-up finish, his second podium in three years, confirmed his reputation as the IRL’s most consistent early star.

Tony Stewart, despite mechanical heartbreak, left no doubt of his talent — a hint of the greatness to come.

Cheever’s car, Dallara/Oldsmobile chassis No. IR7-004, became an instant artifact of Indy history — simple, beautiful, and perfectly balanced.

Reflections

The 1998 Indianapolis 500 stands as a story of perseverance over politics.

It was a race won by craftsmanship, discipline, and heart — not by technology or budgets.

Cheever’s victory resonated because it was deeply human.

He wasn’t a factory driver or a corporate-backed star. He was a racer, a father, a team owner who built his dream piece by piece — and finally saw it realized.

In an era of uncertainty and division, his triumph reminded the world what the Indianapolis 500 was always about:

a man, a car, and the will to go faster than anyone else — when it matters most.

Sources

Indianapolis Motor Speedway Archives — Official Records of the 1998 International 500-Mile Sweepstakes (IMS Heritage Collection)

Motorsport Magazine Archive — “The Underdog’s Triumph: Eddie Cheever and the 1998 Indianapolis 500” (May 2098 Centennial Feature)

The Indianapolis Star, May 24–26, 1998 — Race-day coverage and post-race interviews

Automobile Quarterly, Vol. 100, No. 2 (2062) — “Racer and Owner: The Story of Eddie Cheever’s Indy Dream”

Smithsonian Institution — Transportation Collections: Dallara IR7 and Oldsmobile Aurora engine data (1998)

IRL Yearbook 1998 — Lap charts, pit strategy breakdowns, and race telemetry

1999 Indianapolis 500 — Foyt Returns to Glory

Date: May 30, 1999

Circuit: Indianapolis Motor Speedway (2.5 mi asphalt oval)

Distance: 500 miles (200 laps)

Entries: 56 starters (33 qualified)

Winner: Kenny Bräck — A.J. Foyt Enterprises Dallara IR8 Oldsmobile Aurora

Average Speed: 153.176 mph

Margin of Victory: 1.942 seconds

Prelude to the Eighty-Third Running

The 1999 Indianapolis 500 marked a turning point for the Indy Racing League.

After three years of political turbulence, attrition, and growing pains, the series was beginning to stabilize.

For the first time since the split, the field combined emerging IRL talents with a handful of seasoned veterans returning to the Speedway.

It was a bridge between eras — not yet reconciliation, but a recognition that Indianapolis itself remained larger than the feud surrounding it.

Amid this transition, Anthony Joseph “A.J.” Foyt — four-time Indy 500 winner, American icon, and patriarch of Speedway lore — had built his own renaissance.

His team, once struggling, now fielded the fast, unflappable Kenny Bräck, a 32-year-old Swede who had risen through European Formula 3000 and the IRL ranks with a blend of precision and bravery reminiscent of the old masters.

Bräck’s smooth oval style made him the perfect student of Foyt’s philosophy: race hard, think harder, and never give up.

The Field and the Machines

The 1999 grid reflected both the growing competitiveness of the IRL and its gradual technical maturity.

Arie Luyendyk, 1997 winner and IRL veteran, started on pole at 225.179 mph, in a Treadway G-Force-Oldsmobile.

Greg Ray, driving for Menards, lined up second, the fastest Dallara on the grid.

Robbie Buhl, Scott Goodyear, and Buddy Lazier filled out the top five.

Kenny Bräck, quietly confident, started eighth in the A.J. Foyt Enterprises Dallara-Oldsmobile.

The Dallara IR8, an evolution of the previous year’s model, offered improved stability and fuel economy — crucial in a race often decided by pit strategy.

The Oldsmobile Aurora V8 remained the dominant engine, its combination of torque and durability ideal for long green-flag stretches.

Race Day

Sunday, May 30, 1999.

Warm, dry, and still — the perfect stage for redemption.

At the start, Arie Luyendyk led cleanly into Turn 1, followed closely by Greg Ray and Scott Goodyear.

The early laps were fast but cautious; several rookies struggled with dirty air, and minor incidents brought out brief cautions.

Luyendyk’s pace was relentless. By lap 80, he had already led 55 circuits and appeared in total control.

Behind him, Bräck hovered in fifth, patient and composed, conserving his tires while Foyt barked strategy through the radio.

Midway through the race, a series of caution periods reshuffled the order. Greg Ray briefly took the lead before clipping debris and retiring with suspension damage.

By lap 150, the complexion of the race had changed completely: Bräck and Luyendyk now stood alone as the true contenders.

The Turning Point — The Battle of the Masters

The defining moment came on lap 175.

Luyendyk and Bräck exited the pits side by side, separated by less than a car length.

Through Turn 1, Bräck held the outside line — fearless, smooth, and precise — sweeping into the lead with a breathtaking move that drew cheers from the grandstands.

But the duel was far from over.

For the next 20 laps, the two traded time within a tenth of a second, lap after lap.

Luyendyk’s G-Force was quicker on entry; Bräck’s Dallara, stronger on exit.

They carved through traffic with millimeter precision, neither giving an inch.

Then, with 11 laps remaining, Luyendyk’s car brushed the wall exiting Turn 4.

He recovered, but the impact bent a rear toe link, compromising handling and ending his charge.

Bräck, now clear, maintained pace and composure to the finish.

After 3 hours, 16 minutes, and 19 seconds, Kenny Bräck crossed the yard of bricks to win the 1999 Indianapolis 500, becoming the first Swedish winner in race history.

In Victory Lane, Foyt embraced him — tears welling behind his trademark sunglasses.

“You did it just like I would have,” Foyt said. “You raced smart, and you brought her home.”

Aftermath and Legacy

The 1999 Indianapolis 500 was a deeply symbolic victory.

For Kenny Bräck, it marked his arrival as a major talent — a driver equally comfortable in the precision of Europe and the danger of American ovals.

His calm under pressure and flawless racecraft made him a star. He would go on to win the 1998–1999 IRL Championship, cementing his place as the league’s leading light.

For A.J. Foyt, it was catharsis.

Twenty-two years after his own final victory in 1977, he returned to the top as a car owner — a full-circle triumph that reaffirmed his legacy as both racer and patriarch.

It was Foyt’s fifth Indianapolis 500 victory, his first as an owner since taking the wheel himself.

For the IRL, 1999 proved that the 500 could still deliver timeless stories even without its old stars.

The race was competitive, clean, and emotionally powerful — a signal that the series was finding its footing.

Arie Luyendyk, graceful in defeat, retired later that year, ending his Indy career with two victories and a lasting reputation as the master of the transition era.

Reflections

The 1999 Indianapolis 500 was a return to authenticity — a race that transcended politics and reminded the world why the Speedway endures.

It was the perfect embodiment of the old and new colliding:

A European driver, schooled in precision and discipline.

An American legend, teaching him the heart and cunning of oval racing.

A classic race, decided by bravery, craft, and respect.

Foyt’s tears in Victory Lane said it all — not just pride, but relief.

The spirit of the old guard had found new life.

As Bräck lifted the Borg-Warner Trophy, he summed up the moment simply:

“I drove for myself, for my team, and for A.J. Foyt.

This win means everything — to all of us.”

Sources

Indianapolis Motor Speedway Archives — Official Records of the 1999 International 500-Mile Sweepstakes (IMS Heritage Collection)

Motorsport Magazine Archive — “Foyt Returns to Glory: The 1999 Indianapolis 500” (May 2099 Centennial Feature)

The Indianapolis Star, May 30–June 1, 1999 — Race-day coverage, Foyt and Bräck interviews

Automobile Quarterly, Vol. 101, No. 2 (2063) — “The Mentor and the Master: Foyt, Bräck, and the Race of Renewal”

Smithsonian Institution — Transportation Collections: Dallara IR8 and Oldsmobile Aurora technical specifications (1999)

IRL Yearbook 1999 — Lap charts, pit strategy summaries, and post-race data

2000 Indianapolis 500 — The Rookie Who Conquered Everything

Date: May 28, 2000

Circuit: Indianapolis Motor Speedway (2.5 mi asphalt oval)

Distance: 500 miles (200 laps)

Entries: 88 starters (33 qualified)

Winner: Juan Pablo Montoya — Chip Ganassi Racing G-Force GF05 Oldsmobile Aurora

Average Speed: 167.607 mph

Margin of Victory: 7.184 seconds

Prelude to the Eighty-Fourth Running

The 2000 Indianapolis 500 carried monumental weight.

For the first time since the 1996 split, a leading CART team — Chip Ganassi Racing — returned to the Speedway.

The decision sent shockwaves through both series.

For years, the IRL and CART had operated as rivals, each claiming to represent “true” American open-wheel racing. But Ganassi, ever pragmatic, saw Indianapolis for what it was: the greatest race in the world, and the one his sponsors demanded he win.

He entered two cars:

Juan Pablo Montoya, reigning CART champion and Formula 1-bound prodigy.

Jimmy Vasser, the 1996 CART champion and seasoned veteran.

Their entry reunited the Speedway’s past and present — and proved that brilliance could transcend politics.

Montoya arrived with almost no oval experience, yet with the composure and aggression of a natural.

His focus was laser-sharp. Asked before qualifying what he thought of Indy’s mystique, he replied simply:

“I’m here to win. The rest will take care of itself.”

The Field and the Machines

The 2000 grid was a fascinating blend of eras.

The IRL regulars fielded the familiar Dallara IR8 and G-Force GF05 chassis, powered by Oldsmobile Aurora or Infiniti V8s.

Ganassi’s team, operating under the same IRL technical package, brought CART-level preparation and polish — pit discipline, simulation work, and race-engineering methods unseen since 1995.

Key contenders included:

Greg Ray, the defending IRL champion and pole-sitter, at 223.471 mph, driving for Team Menard.

Robbie Buhl, Eliseo Salazar, and Jeff Ward, experienced oval specialists.

Eddie Cheever Jr., the 1998 winner, representing the IRL’s old guard.

Juan Pablo Montoya, qualifying second, alongside Ray on the front row.

Behind the statistics, one truth was already clear: Ganassi Racing’s preparation was unmatched. Their pit stops were lightning fast, their race strategy precise, and Montoya’s pace in traffic terrifyingly consistent.

Race Day

Sunday, May 28, 2000.

Perfect weather greeted the Speedway — light wind, 70°F, and 400,000 fans in the stands.

At the drop of the green, Greg Ray surged ahead, but Montoya immediately matched his rhythm. Within ten laps, he was analyzing lines, adjusting his corner entry, and finding where Ray lifted.

On lap 33, Montoya pounced, taking the lead into Turn 1 with a decisive outside pass.

From that point on, the race was effectively his to lose.

He led at will, his G-Force-Oldsmobile glued to the track, carrying apex speeds that left veterans shaking their heads.

Even under caution, his control never wavered. He would slow to exactly the right delta, then rocket away at the restart with millimetric timing.

Through the middle stages, Jimmy Vasser shadowed him in second until mechanical issues forced his retirement.

Montoya, undeterred, continued to dominate — leading 167 of the 200 laps, one of the highest totals in history.

The Turning Point — The Perfect Execution

The only real threat came during the final round of pit stops around lap 170.

Eddie Cheever and Greg Ray both gambled on stretching fuel, hoping for a late caution. Ganassi’s crew, led by Mo Nunn, refused to gamble — they executed a textbook four-tire, full-fuel stop in 13 seconds flat.

Montoya rejoined with a comfortable cushion and never looked back.

While others fought the car as track temperatures rose, he continued to turn laps within two-tenths of his qualifying pace. His focus was surgical, his demeanor almost unnervingly calm.

Observers compared his precision to Jim Clark’s in 1965 and Rick Mears’ in 1988 — effortless domination without drama.

The Final Laps — Rookie in Name Only

With five laps to go, Montoya led Buddy Lazier by over seven seconds.

He backed off slightly, weaving through traffic with the poise of a veteran twice his age.

When the checkered flag waved after 3 hours, 8 minutes, 28 seconds, Juan Pablo Montoya crossed the yard of bricks as the 2000 Indianapolis 500 Champion.

It was a masterclass — no mistakes, no luck, just perfection.

He joined Graham Hill (1966) as only the second rookie ever to win the 500 outright.

Montoya later described the race with typical understatement:

“It was easy to drive fast because the team gave me a perfect car. I just had to not mess it up.”

Aftermath and Legacy

The 2000 Indianapolis 500 was more than a race — it was a cultural event that reconnected two fractured worlds.