Le Mans 1923 - 1939

Pre-War Experimental

1923 — The Birth of Endurance

Hour 0 (4:00 PM) — The Beginning of Forever

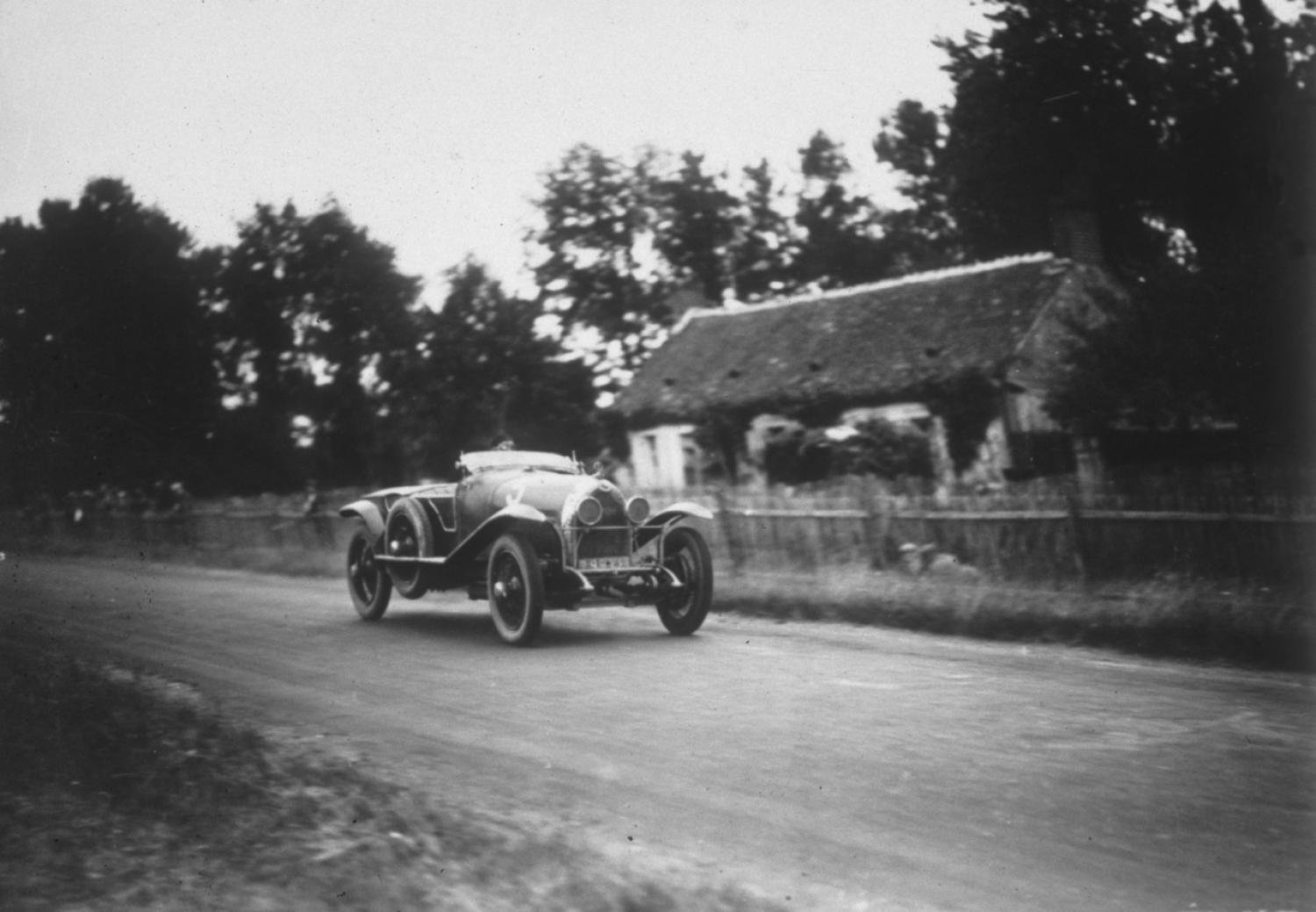

The drizzle begins before the engines even catch. Thirty-three cars sit in loose formation along the public roads south of Le Mans — French tricolors flapping above a damp crowd. No one yet understands they are watching the dawn of something eternal. The flag drops, and a roar rises from the hedgerows. The machines surge forward in clouds of spray and gravel, headlights unlit but nerves ablaze. The Chenard & Walcker #9 rockets away with a clean getaway, its two-man crew of Lagache and Léonard trading short glances — partners in a 24-hour pact of patience and precision.

Hour 1 (5:00 PM) — Settling the Rhythm

The field stretches. Bentley’s lone entrant muscles forward, trading early blows with the French pack. Stones slash into paint and glass; tires hiss across slick tarmac. Already, the race feels longer than it looks. Crews hunch in narrow pit stalls built from wood and sandbags, refueling by hand, timing laps with pocket watches. The Chenard runs steady — unhurried, unsentimental.

Hour 2 (6:00 PM) — The Rain Deepens

Raindrops swell into torrents. Headlamps flicker to life, slicing pale beams through mist. A few cars slide off course; others limp in with punctures. The Bentley suffers a cracked lamp and soldiers on half-blind. Yet the rhythm of the race begins to take shape — not speed against speed, but will against will.

Hours 3–4 (7:00 PM – 8:00 PM) — Into the Dark

Night falls early under heavy clouds. The circuit becomes a black ribbon framed by farmhouses and lanterns. Drivers guide themselves by memory more than sight. The Chenard maintains a metronomic pace, while lesser machines overdrive and falter. A sense of awe descends — this is no ordinary contest; this is survival.

Hours 5–8 (8:00 PM – Midnight) — Attrition Begins

The storm shows no mercy. Mud cakes wheels and clogs radiators. The pit crews’ faces shine with oil and rainwater. Some entries withdraw silently; their engines too battered to continue. Yet the leaders persist, headlights dancing through puddles like ghosts. Lagache and Léonard swap seats, each taking brief rest before returning to the mechanical storm.

Hours 9–12 (Midnight – 3:00 AM) — The Longest Night

Past midnight, the air chills to the bone. Drivers’ goggles frost, lamps flicker, and the circuit feels endless. The Chenard’s rhythm never breaks — gear changes crisp, engine tone unwavering. Bentley’s wounded car gamely pushes on, its driver guided only by memory and instinct. One by one, competitors fade into darkness.

Hours 13–16 (3:00 AM – 6:00 AM) — Dawn’s Promise

The eastern horizon glows faintly violet. Those who have endured this long now drive as if in a trance. Fatigue blurs time itself; minutes dissolve into the hum of engines. Pit stops are conducted in whispers — every bolt tightened is a prayer. When the first light spills across Sarthe, fewer than twenty cars still move under their own power.

Hours 17–20 (6:00 AM – 9:00 AM) — The Morning March

With the dawn comes resolve. The Chenard still leads, running with elegance amid wreckage. Bignan gives distant chase, its drivers clinging to faint hope. The Bentley limps valiantly, its bodywork cracked, its soul intact. The circuit, once festive, now feels sacred — every corner a test of endurance’s meaning.

Hours 21–23 (9:00 AM – 11:00 AM) — Holding the Line

The survivors now focus only on finishing. The Chenard’s lead is secure but fragile — one mistake could erase twenty-three hours of perfection. The car hums past pit wall, coated in grime yet composed. Lagache keeps his throttle measured, Léonard nods silently. Behind them, the world watches in disbelief that such a race can even be finished.

Hour 24 (11:00 AM – Noon) — The First of Many

As the clock strikes noon, a final cheer erupts. The Chenard & Walcker #9 crosses the line, its two drivers waving to soaked marshals and stunned onlookers. They have covered 128 laps — 2,209 kilometers — without failure. The first winners of Le Mans, their names now etched into eternity.

Bentley finishes heroically in fourth, having proven British engineering can stand alongside France’s finest. Only a handful of machines remain moving when the flag falls. The field is battered, the circuit scarred — but the legend is born.

Aftermath

That afternoon, when the engines finally fall silent, Lagache and Léonard step from their car to polite applause that soon swells into something grander. No one quite knows it yet, but this small experiment in the French countryside has changed motor racing forever. Le Mans will return — fiercer, faster, and every bit as unforgiving — and endurance will forever stand as the ultimate measure of man and machine.

Results

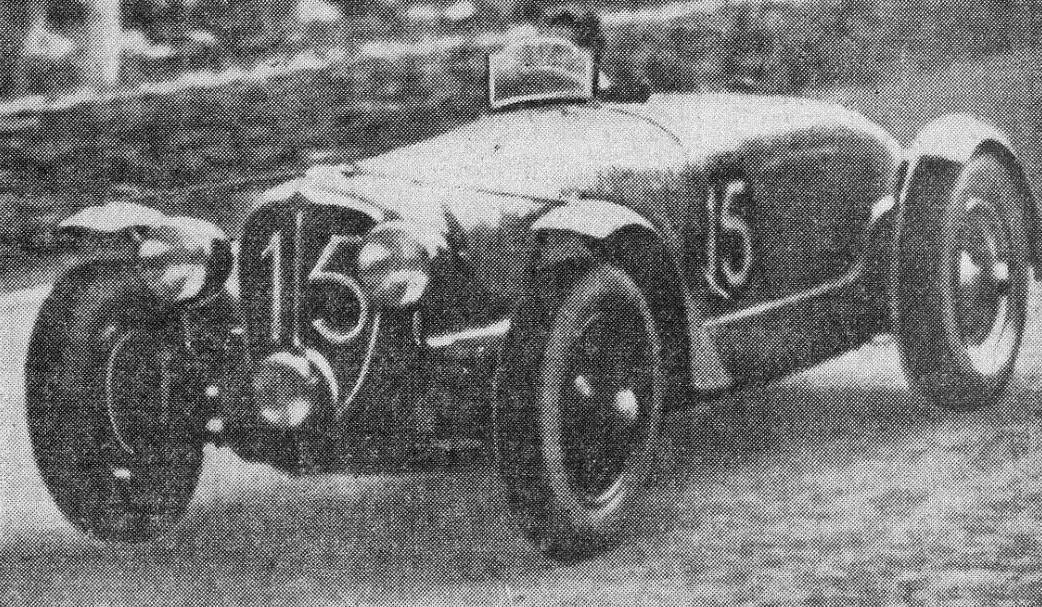

Winners: André Lagache / René Léonard — Chenard & Walcker Type U3 15 CV Sport

Distance: 128 laps (≈ 2,209 km)

Average Speed: ≈ 92 km/h

Second: Raoul Bachmann / Christian Dauvergne — Chenard & Walcker

Third: Fernand Bignon / Raoul De Zúñiga — Bignan 2924 cc

Fourth: John Duff / Frank Clement — Bentley 3 Litre

Sources

24 Hours of Le Mans Official Archive — Automobile Club de l’Ouest (ACO)

The Race — “How Le Mans Got Its Start (1923)”

Goodwood Road & Racing — “The Very First Le Mans”

Motor Sport Magazine — “The First Le Mans Winners (1923)”

The Guardian — “Broken Lights and a Policeman’s Bike: Bentley’s Run at Le Mans 1923”

Wikipedia — 1923 24 Hours of Le Mans Historical Record

1924 — The First Victory for Bentley

Hour 0 (4:00 PM) — A New Dawn, A New Contender

On 14 June 1924 the field is bigger, more ambitious, and the sun beats down on Le Mans. Forty-one cars line up under heat and expectation. The 4-litre Chenard-Walcker of Lagache / Léonard carries prestige and reputation, and it bursts forward at the start, staking a claim early. But from the stands, there’s a ripple of excitement about a slender dark green Bentley 3-litre driven by John Duff and Frank Clement — quieter, leaner, but built for the long war of 24 hours.

Hour 1 (5:00 PM) — The Chase Unfolds

The Chenard-Walcker leader surges ahead, setting a blistering pace. But the engine note betrays strain. As the first laps tick away, the Bentley sneaks into second, its components calm, its breath steady. Around them, several cars begin to falter — overheating, fuel pressure wavering, tires blistering in the heat. The pits buzz with urgent adjustments.

Hour 2 (6:00 PM) — Flames on Mulsanne

Then disaster. On the Mulsanne Straight, the lead Chenard-Walcker bursts into flame — a moment of tragedy and drama. The flame flickers, the machine falters, the pioneers’ bid collapses. The Bentley inherits the mantle of contention. The race becomes a duel between the Lorraine-Dietrich cars and the British upstart, shifting the narrative of the contest.

Hours 3–4 (7:00 – 8:00 PM) — Night Looms, Pressure Builds

The heat gives way to dusk, and headlights begin their vigil. The Lorraine team pushes three cars in tandem, hoping strength in numbers will overwhelm the lone Bentley. Duff and Clement pace carefully — fast, but never foolish. Every crackle, every shudder, is watched. The field is thinning: retirements multiply.

Hours 5–8 (8:00 PM – Midnight) — Survival Mode

Through the early night, the Lorraine trio trade place among themselves, but one by one they fall back — mechanical wear, clutch trouble, or worse. The Bentley glides through the darkness, untraumatized. In the pits, mechanics top off oil, cool fluids, and swap personnel. The Bentley breathes easier, its strategy unfolding quietly.

Hours 9–12 (Midnight – 3:00 AM) — The Dark Hours

Midnight deepens the field’s suffering. Drivers’ vision dulls, nerves fray, and debris becomes a mortal hazard. The Lorraine hopes flicker — one car slows, then another. The Bentley remains consistent. Exhausted, drivers take short rests; the alternation of motion and pause is a ritual now.

Hours 13–16 (3:00 – 6:00 AM) — Dawn’s Edge

First light looms but seems distant. The Bentley still leads, though with challengers fading. The road is scarred; the circuit pummeled. The pace is relentless. Each lap is a triumph over fatigue. The mechanics lean in shadows; drivers drink coffee, massage limbs, steady breathing.

Hours 17–20 (6:00 – 9:00 AM) — Day Breaks, Stakes Rise

Light returns, and reality sharpens. The lone Bentley faces no rival—Lorraine’s cars are either behind or broken. Duff and Clement gauge what remains: push too hard, risk the final hours; restrain too much, lose pace. The balance is delicate, the lead precarious, but they hold.

Hours 21–23 (9:00 – 11:00 AM) — The Final Gambit

With only hours to go, strategy crystallizes. The Bentley’s crew runs only essential stops. The car slides through the circuit with grace and grit, coated in grime but running true. Duff’s hands are steady; Clement’s judgment calm. The world waits for the moment when the green car crosses into myth.

Hour 24 (11:00 AM – Noon) — Triumph at Last

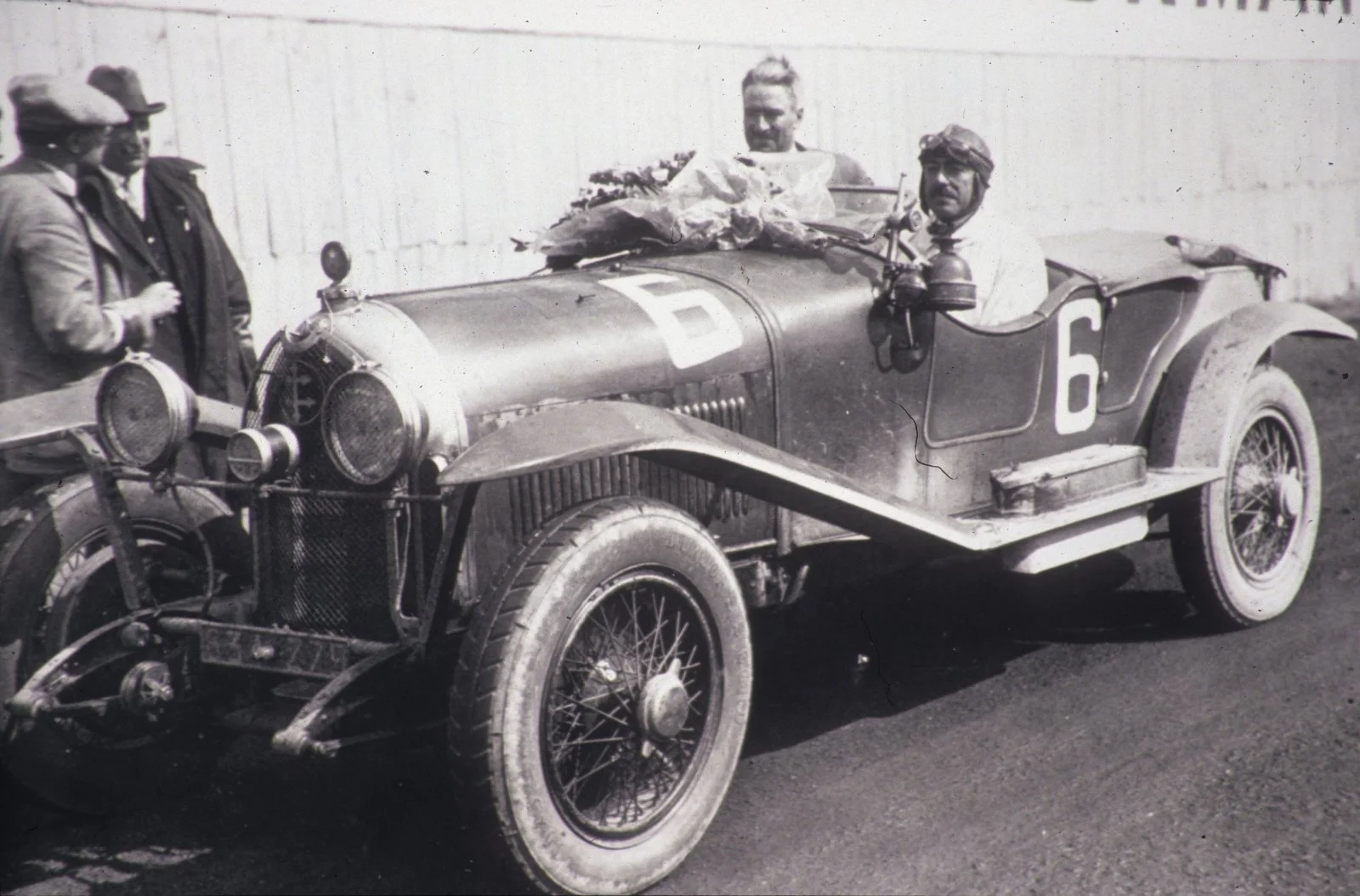

As time lapses toward noon, the Bentley glides across the finish line. Duff and Clement emerge, exhausted but elated. They have done what no British team had yet: won Le Mans. The battlefield of broken machines, scorched parts, and mechanical failure lies behind them. In victory, they cradle the first of many triumphs for Bentley.

Aftermath & Results

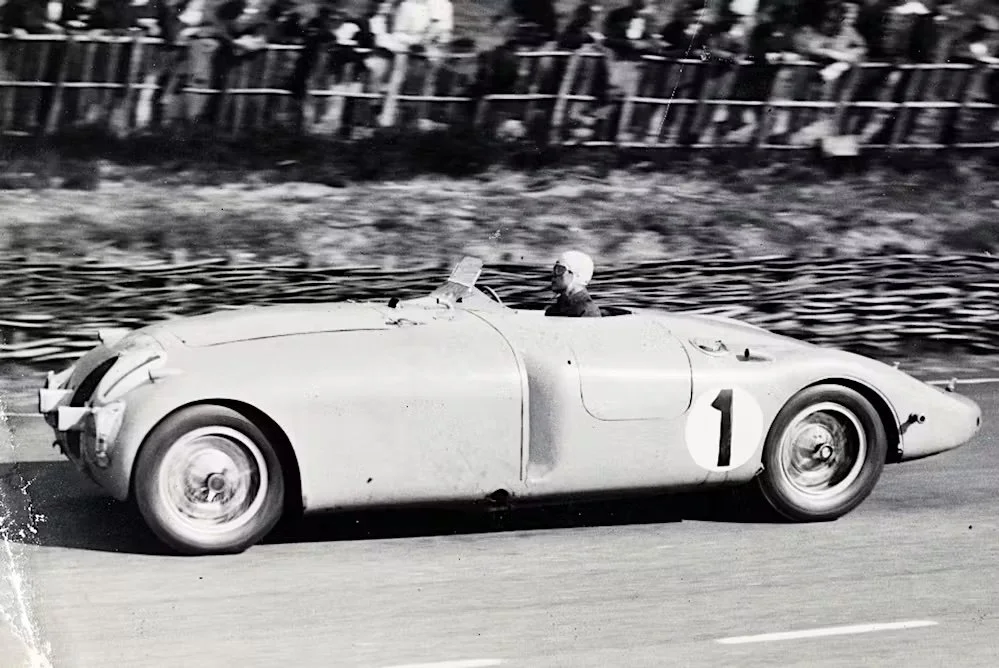

John Duff and Frank Clement, in a Bentley 3-Litre Sport, won the 1924 24 Hours of Le Mans — the first victory by a British constructor.

They bested the remaining Lorraine-Dietrich entries, proving that endurance and discipline could upend raw pace.

Of the 41 starters, only 12 cars finished the full 24 hours under the tougher conditions and stricter target distances.

It was a turning point: a new national rival in endurance racing, and a sign of things to come from Bentley and the so-called “Bentley Boys.”

Sources

1924 24 Hours of Le Mans — Wikipedia Wikipedia

Motorsport Magazine / database on 1924 event Motor Sport Magazine

Experience Le Mans — competitors and results for 1924 experiencelemans.com

24h-lemans.com — Bentley’s history & first win in 1924 24h-lemans.com+1

Frank Clement / John Duff driver biographies Wikipedia+1

1925 — When Lorraine Rose to the Top

Hour 0 (4:00 PM) — A New Ritual Begins

On 20 June 1925 the circuit thrums anew. This year, the start is relocated to the Mulsanne Straight, and for the first time drivers sprint to their cars in the Le Mans “grand start” tradition—feet pounding gravel, overcoats flapping, engines idling. Forty-nine cars line up, the air heavy with warm sun and expectation. The green flag snaps down, and the field storms forward, some engine fires sputtering, others roaring strong.

Hour 1 (5:00 PM) — The Early Shuffle

Immediately the race takes on shape. Bentleys surge, Lorraine-Dietrichs press. In the glare of day, overheating and mechanical strain begin to bite. The Chenard-Walcker entries aim for consistency, quietly threading their way through attrition. But one car, in particular, stands out—a green Lorraine B3-6, its drivers weaving through the pack with quiet confidence.

Hour 2 (6:00 PM) — Scuffles and Setbacks

The circuit reveals its hazards: stones, washouts, vibration. Several entries suffer punctures or damage. One Bentley falters, its mechanics struggling to right it. The Lorraine holds pace, its pulse calm amid turbulence. The rivals jostle, but none decisively break away.

Hours 3–4 (7:00 – 8:00 PM) — Under the Dimming Sky

The sun slants low. Tire wear, engine temperatures, and clutch slips begin to tell. Some teams gamble—pushing hard to gain ground; others ease off, hoping to preserve their machines. The Lorraine B3-6 remains in the top echelons, fending off challengers. Behind it, several ambitious cars fall silent in the pits.

Hours 5–8 (8:00 PM – Midnight) — Night’s Threats

Darkness deepens. Headlights carve arcs across the track. The field thins: some machines drop out entirely, others limp under the weight of damage or fatigue. The Lorraine’s crew works efficiently during stops—cooling fluids, topping oil, keeping drivers alert. The car seems built for this night: steady, relentless.

Hours 9–12 (Midnight – 3:00 AM) — The Midnight Gauntlet

Midnight brings its own trials. Night air chills, driver fatigue sets in, and visibility blurs. Mist and spray hang low in corners. Some cars slow considerably or retire outright. But the Lorraine presses on, lapping steadily, strategy locked in. The chase seems distant now.

Hours 13–16 (3:00 – 6:00 AM) — Dawn’s Edge

The eastern sky begins its pale glow. The circuit lies battered and weary, but the Lorraine continues as if untouched. Rivals are either far behind or no longer moving. The pace is methodical. Drivers sip cool water, flex cramped limbs, stare ahead through wakeful eyes. The distance to go shrinks, yet the path remains treacherous.

Hours 17–20 (6:00 – 9:00 AM) — Light Returns, Pressure Rises

With morning, visibility sharpens. Each corner demands renewed respect. The Lorraine leads, its tires worn, its engine humming in rhythm. A fading Bentley or Sunbeam may attempt a late lunge, but none can truly challenge. Crews hold their breath: one misstep now could lose everything.

Hours 21–23 (9:00 – 11:00 AM) — The Final Gamble

In the final hours, every lap becomes a test of nerve. The Lorraine crew foregoes unnecessary stops; the car glides on fumes of grit and endurance. The chase is faint, the gaps real. The driver pair stretch, knowing the finish looms but not assured. The sun climbs, shadows shorten, and the track echoes with remembrance of those who fell behind.

Hour 24 (11:00 AM – Noon) — The Crown of Victory

As the clock approaches noon, the Lorraine B3-6 crosses the finish line. Gérard de Courcelles and André Rossignol step free, exhausted, elated. They have covered 2,233.982 km at an average 93.082 km/h. Under bright skies and applause, Lorraine claims its first Le Mans victory. The field behind is thin, but the triumph is absolute.

Aftermath & Full Results

Winner:

Gérard de Courcelles / André Rossignol in a Lorraine-Dietrich B3-6 Sport

Distance: 2,233.982 km

Average Speed: 93.082 km/h

Margin to 2nd: ~73.362 km

Other Highlights / Awards:

Fastest Lap: André Lagache, Chenard & Walcker, 9′10″ (≈ 112.987 km/h)

Index of Performance: Raymond Glaszmann / Manso de Zúñiga, Chenard & Walcker

Triennial Cup Winner: Robert Sénéchal / Albéric Loqueneux, Chenard & Walcker

Biennial Cup Winner: Raymond Glaszmann / Manso de Zúñiga, Chenard & Walcker

Notes:

This race marked the debut of the Le Mans “run-to-car” start, adding spectacle and danger.

Tragically, driver Marius Mestivier lost his life in an accident during the event.

The victory positioned Lorraine-Dietrich as a real rival to Bentley in endurance prestige — a rare shift in the early years.

Sources

24h-lemans.com — “90 Years Ago: The 1925 24 Hours of Le Mans”

UniqueCarsAndParts — “Le Mans 1925” race data

RacingSportsCars — 1925 Le Mans official results

Wikipedia — “1925 24 Hours of Le Mans”

Motorsports Database — race overview

Automuseum / archival historical commentary

1926 — Bentley’s Return and Lorraine’s Dynasty

Hour 0 (4:00 PM) — The Curtain Rises Again

The summer of 1926 greets Le Mans with bright skies and the scent of petrol hanging over the Sarthe fields. Thirty-seven cars line the grid, engines burbling in uneven chorus. The flag falls, and once again drivers sprint across the tarmac to their machines — the ritual now unmistakably Le Mans. Dust swirls, crowds cheer, and the 24 Hours begins in earnest.

The defending champions, Lorraine-Dietrich, arrive as favorites. Their blue B3-6s are proven, elegant, relentless. Bentley, bruised but unbowed after 1924’s glory and 1925’s disappointment, returns with one car for Duff and Clement, the duo who first brought Britain victory. This time, endurance will decide which marque’s legend grows.

Hour 1 (5:00 PM) — Early Heat and Quick Paces

The first laps are feverish. Lorraine-Dietrichs surge to the front — three of them moving as one, their straight-sixes humming with mechanical confidence. The Bentley charges behind, the only British flag amid a sea of French blue. The circuit shimmers under the sun, and already the slower entrants are losing ground.

Hour 2 (6:00 PM) — Bentley’s Misfortune

Barely two hours in, misfortune strikes. The Bentley’s rear axle begins to groan; vibration worsens. In the pits, Duff and Clement confer with mechanics, tightening fasteners, refueling, adjusting bearings. But the issue returns — a wounded rhythm beneath the bonnet. Their hopes fade before night even falls.

Hours 3–4 (7:00 – 8:00 PM) — Lorraine Asserts Control

With Bentley hobbled, the Lorraines stretch away. Car #4, driven by Robert Bloch and André Rossignol, sets a relentless pace — smooth, confident, without drama. The team’s formation-running strategy holds: one car leading, one shadowing, one ready to inherit should trouble come.

The rest of the field fights for the scraps. Chenard & Walcker, fast but fragile, chase gamely, while several lesser entries bow out before dusk.

Hours 5–8 (8:00 PM – Midnight) — Nightfall’s Trial

Darkness drops with heavy cloud and cool air. The track, now gleaming and slick, demands precision. Headlamps tremble over stone-lined corners. The Lorraine trio, evenly spaced, begin the night’s long march — their lead comfortable, yet never relaxed.

Bentley soldiers on despite its mechanical ailments, its lap times tumbling. In the pits, Duff’s frustration is visible, but so too is his resolve: they will finish, no matter how far down the order.

Hours 9–12 (Midnight – 3:00 AM) — Endurance Over Elegance

The small hours expose the fragile. One Chenard retires, a Delage follows, their engines cracked from strain. Lorraine continues unbothered, a picture of methodical engineering. Drivers swap every few hours, oil is checked by lantern light, and timing clerks scribble through the chill. The B3-6 seems untouchable.

Hours 13–16 (3:00 – 6:00 AM) — The Quiet Before Dawn

The night softens into dawn mist. The lead Lorraine purrs on, its rhythm hypnotic. Bloch and Rossignol, unhurried yet precise, maintain an average speed north of 90 km/h — formidable in these conditions. By sunrise, fewer than twenty cars remain circulating.

Hours 17–20 (6:00 – 9:00 AM) — Morning Light, Uneasy Calm

The early light brings both clarity and fatigue. The blue Lorraines flash by grandstands now draped in dew. One car drops slightly with gearbox trouble, but the other two continue faultlessly. The lead machine — Bloch and Rossignol — runs smooth, confident, its engine note unwavering. Mechanics nod quietly; their work, for once, is perfect.

Hours 21–23 (9:00 – 11:00 AM) — Preserve the Lead

In the closing hours, Lorraine’s team orders discipline. Speeds drop slightly. They can afford it. The crowd, sensing inevitability, begins to celebrate already. Bentley limps on in defiance, finishing what it started — symbolic of the endurance spirit itself.

Hour 24 (11:00 AM – Noon) — Back-to-Back Triumph

At noon, the blue Lorraine crosses the line to waves of cheers and the crackle of cameras. The French marque has done it again — a second consecutive victory, this one a sweep of the podium. Bloch and Rossignol embrace at the pit wall, smeared in oil and triumph.

Behind them, teammates Courcelles and de Gavardie finish second, Stalter and Brisson third. The three Lorraines fill the rostrum, sealing one of the most dominant performances the race has ever seen.

Aftermath & Results

Winners: Robert Bloch / André Rossignol — Lorraine-Dietrich B3-6

Distance: 2,552.029 km

Average Speed: 106.315 km/h

Second: Gérard de Courcelles / Marcel de Gavardie — Lorraine-Dietrich B3-6

Third: Henri Stalter / Louis Brisson — Lorraine-Dietrich B3-6

Fastest Lap: Rossignol — 8′25″ (approx. 113 km/h)

Notes:

The victory marked Lorraine-Dietrich’s final factory win at Le Mans before the marque’s withdrawal from racing.

Bentley’s mechanical misfortune delayed its resurgence until 1927, when the Bentley Boys would begin their reign.

1926 stands as the only year to date when a single manufacturer swept all three podium positions at Le Mans.

Sources

Automobile Club de l’Ouest (ACO) — Official 24 Heures du Mans Archive

24h-lemans.com — “Lorraine’s Golden Years (1925–1926)”

Motorsport Magazine Database — 1926 24 Hours of Le Mans Results

RacingSportsCars.com — Race Summary and Statistics

Wikipedia — 1926 24 Hours of Le Mans

Goodwood Road & Racing — “Bentley and the French Years” Feature

1927 — The White House Crash

Hour 0 (4:00 PM) — The Calm Before the Storm

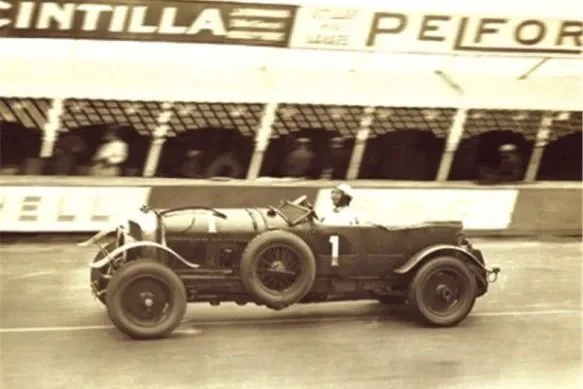

The late-June sun hangs low over the Sarthe countryside. Forty-one machines line up, shining under a blue sky—Lorraine-Dietrich, Ariès, Salmson, and three green Bentleys. The crowd is restless; British flags wave beside French tricolors. At the signal, the drivers sprint across the road, leaping into their cockpits in the now-iconic Le Mans start. Engines fire, tires spin, and a thunderous roar rolls down the Mulsanne Straight.

Bentley’s hopes rest on three cars: the works entry for Dudley Benjafield and Sammy Davis, another for Leslie Callingham and George Duller, and a privateer driven by Frank Clement and John Duff. All eyes turn to the British green as they streak past the pits. This is the year they intend to reclaim the crown.

Hour 1 (5:00 PM) — A Strong Opening

The first hour is electric. The Bentleys push hard, establishing themselves near the front. Lorraine-Dietrichs, still confident from their previous dominance, match them lap for lap. The course is dusty and fast; new surface sections make cornering treacherous. For now, all three Bentleys run clean.

Hour 2 (6:00 PM) — Disaster on the Straight

Then, chaos. Just after 6 PM, approaching the Maison Blanche (“White House”) corners, the track clogs with slower traffic. A Th. Schneider spins across the racing line. One by one, cars pile into the wreckage. Metal, oil, and smoke scatter across the road. The accident eliminates more than a dozen competitors in moments. Two of the Bentleys are caught in the melee—Callingham’s and Duff’s—both destroyed.

Only one remains: the #3 Bentley 3 Litre Sport of Benjafield and Davis.

Hours 3–4 (7:00–8:00 PM) — Through the Wreckage

The circuit is chaos. Marshals clear debris, smoke hangs thick in the air. Davis steers the surviving Bentley through the wreck with one headlamp gone and the left front wing bent over the tire. He presses on regardless. In the pits, Bentley’s team watches in silence; the car is crippled, but not dead.

Hours 5–8 (8:00 PM – Midnight) — Bentley Fights Back

Night settles over a shaken race. Many entries withdraw from damage or fear. The lone Bentley circles methodically, the bodywork flapping, lights dim, steering skewed. Davis nurses it with care, coaxing speed from the wounded machine. Competitors pity the sight—then realize it’s still gaining time.

Hours 9–12 (Midnight – 3:00 AM) — Rain and Resolve

Rain falls in the early hours, turning the course slick. The Lorraine-Dietrichs suffer gearbox and electrical gremlins. Through sheer consistency, the battered Bentley climbs into the top five. Benjafield takes over, driving by instinct through fog and fatigue. They are no longer racing others—they are defying circumstance itself.

Hours 13–16 (3:00 – 6:00 AM) — The Dawn Charge

At first light, the pit crew huddles around the car, straightening fenders, re-wiring lamps, and refilling fluids. Davis returns to the wheel and pushes. To everyone’s disbelief, the Bentley’s lap times rise. By sunrise, they are leading. The battered green machine, once nearly wrecked, now commands Le Mans.

Hours 17–20 (6:00 – 9:00 AM) — A Race of Survival

The morning reveals a decimated field—only 17 cars remain. Lorraine-Dietrich’s challenge collapses; one after another their engines surrender. Benjafield coaxes the wounded Bentley through each lap, never over 100 km/h on the straights, never losing rhythm. The car groans in protest, but holds.

Hours 21–23 (9:00 – 11:00 AM) — Every Second Counts

The final stretch is agony. The gap to the second-placed Salmson shrinks, then widens again as fatigue grips both sides. The Bentley’s oil pressure flickers, its tires worn to threads. Yet the two drivers, black-eyed and grim, refuse to yield. Davis, recalling later, said it felt as if “the car willed itself onward.”

Hour 24 (11:00 AM – Noon) — Triumph in Ruin

At last, after 24 grueling hours, the green #3 Bentley limps past the flag. The crowd erupts. Its body is dented, its paint charred, one headlamp smashed—but it has won. Benjafield and Davis embrace beside their car, the roar of the British contingent echoing through the stands.

They have conquered not by perfection, but by sheer survival.

Aftermath & Results

Winners: Dr. Dudley Benjafield / Sammy Davis — Bentley 3 Litre Sport

Distance: 2,617.41 km

Average Speed: 109.06 km/h

Second: Georges Casse / Robert Lallement — Salmson GS 8

Third: Jean Roussel / Jean Hasley — Tracta Gephyre

Notables:

The “White House Crash” remains one of Le Mans’ defining early incidents, shaping the race’s reputation for chaos and endurance.

The victory saved Bentley’s reputation and ignited the era of the Bentley Boys, whose spirit of bravery and camaraderie became motorsport legend.

The battered winning car was later nicknamed “Old Number Seven”, restored, and displayed as a symbol of resilience.

Sources

Automobile Club de l’Ouest (ACO) — Official 1927 24 Heures du Mans Archive

24h-lemans.com — “The White House Crash: Le Mans 1927”

Motorsport Magazine Archive — Race Report, July 1927 Issue

Goodwood Road & Racing — “Bentley’s Miracle Win of 1927”

RacingSportsCars.com — 1927 Results and Entrant Records

Wikipedia — 1927 24 Hours of Le Mans

1928 — The Distance Duel

Hour 0 (4:00 PM) — The Green Wave Rises

Under a blistering early summer sky, the 33 entrants roar to life. This year, foreign marques outnumber the French for the first time, and Bentley arrives with confidence. As the flag drops, the Bentleys surge forward, the roar of British engines echoing through the Sarthe countryside. Among them is #4, driven by Woolf Barnato and Bernard Rubin, and another with Henry Birkin and Jean Chassagne, already pressing to show their might.

Hour 1 (5:00 PM) — Pace and Promise

The Bentleys push hard from the outset, establishing a lead. But another challenger looms: the American Stutz of Édouard Brisson and Robert Bloch, bullying its way forward. The track, newly resurfaced in places and better lit, allows sharper speeds—still, the distance prize now means every lap counts, not just leading.

Hour 2 (6:00 PM) — Attrition Begins

Two Bentleys and an Ariès already bow out to mechanical failures. The field shrinks. The duel now focuses between Barnato’s Bentley and the Stutz. They trade the lead through corners, their lap times neck-and-neck. Behind them, crews strain to maintain the machines that survive.

Hours 3–4 (7:00 – 8:00 PM) — Night Approaches, Tensions Rise

Twilight deepens. The duel intensifies. Barnato’s Bentley begins to falter slightly—its radiator hisses, temperature rises, foaming water sprays. The Stutz presses, hoping to overtake. But Bloch’s gearbox is fragile, and he must respect that weakness. Around them, other cars retire—Chrysler, Lagonda, Alvis—many beaten by simple failure.

Hours 5–8 (8:00 PM – Midnight) — Survival in the Dark

Darkness falls fully. Drivers lean through corners by instinct, headlights slicing shadows. Barnato nurses the Bentley through rising heat and squeaks; the Stutz presses, sometimes leading, sometimes yielding. They alternate lead, lap after lap, neither giving quarter. The rest of the field is fading rapidly.

Hours 9–12 (Midnight – 3:00 AM) — The Midnight Gauntlet

Midnight sees the field nearly halved. Only 17 cars finish in total. Crews work furiously, spies of failure everywhere. Barnato eases off at times, letting the Bentley cool; Bloch in the Stutz fights bravely, but clutch and gearbox groan under strain. Each passing hour feels like a test of will.

Hours 13–16 (3:00 – 6:00 AM) — Dawn’s Near

In the pre-dawn gloom, the battle continues. Barnato and Rubin in the Bentley hold the narrow advantage. One misstep might cost everything. Birkin in the other Bentley, though he’s set a sensational lap record (8′07″), is too far behind. The leading pair pace themselves, breathing through the final stretch.

Hours 17–20 (6:00 – 9:00 AM) — Daylight Returns

Morning light returns to reveal a wrecked but fighting Bentley, trailing vapor, radiator spewing steam. The Stutz, now suffering gearbox trouble, begins to lose pace. Barnato presses cautiously, ever aware the machine’s limits are near. Every lap is a negotiation: push or preserve?

Hours 21–23 (9:00 – 11:00 AM) — The Final Stretch

Now every second is precious. Barnato times his run. He coaxingly roof the Bentley through its final circuits, free-wheeling on downslopes to ease heat, letting the engine rest where possible. The Stutz, clutch slipping, cannot sustain the pace. The gap grows, then shrinks—tension high to the last lap.

Hour 24 (11:00 AM – Noon) — Victory by a Whisper

In the last half hour, Barnato’s Bentley rolls over the finish line, 128 laps, but by a pain-staking oversight, he arrives too early and must complete an extra lap to qualify. With radiator steaming and speed reduced, he coasts the final circuits. The Stutz overtakes “on paper” but is later un-lapped. Finally, Barnato crosses officially, 13 km ahead—just enough margin in this epic duel.

The crowd erupts. The battered, steaming Bentley, worked nearly beyond endurance, has prevailed in perhaps the closest Le Mans duel yet.

Aftermath & Results

Winners: Woolf Barnato / Bernard Rubin — Bentley 4½ Litre

Distance: 2,669.27 km

Average Speed: ≈ 111.22 km/h

Second: Édouard Brisson / Robert Bloch — Stutz BB Blackhawk

Third: Third place surfaces in the Chrysler entries; a solid but distant run.

Fastest Lap: Henry Birkin (Bentley) — 8′07″ (~127.60 km/h)

Notables:

This was Bentley’s second Le Mans victory and the first distance prize winner.

It marked the inaugural “Coupe à la Distance” awarded to the car that covered the greatest distance, regardless of class.

The margin—13 km after nearly 2,700 km—was razor-thin, making it one of the race’s most dramatic finishes to date.

Birkin’s lap record still stands as one of the most celebrated in early Le Mans lore.

Sources

Motorsport Magazine (July 1928) — “Le Mans 1928 Race Report” Motor Sport Magazine

RacingSportsCars.com — 1928 Le Mans results racingsportscars.com

Wikipedia — “1928 24 Hours of Le Mans” Wikipedia

ExperienceLeMans.com — Competitors & results 1928 Experience Le Mans

24h-lemans.com — 90th anniversary retrospective 24h-lemans.com

Primotipo — historical reflection on Bentley in Le Mans primotipo...

1929 — The Year of the Bentley Sweep

Hour 0 (4:00 PM) — A New Layout, A New Ambition

Gray clouds hang low over Sarthe as the field rolls forward on the updated 16.34-km circuit (a by-pass shortens the track by nearly a kilometer). The roar of Bentleys dominates the grid. Among them, the Speed Sixes sparkle with promise. Birkin and Barnato take the lead from the flag; Clement, Kidston, Benjafield follow close behind. A slender American Stutz prowls near their heels. As the flag drops, engines thunder, dust billows, and the 24-hour war begins.

Hour 1 (5:00 PM) — Lap Record from the Start

Barely a lap in, Birkin stamps his authority with a new lap record: 7m57s from a standing start, immediately setting the tone. Behind him, the Bentleys fan out in formation. A gap forms to the chasing Stutz and Chrysler machines. Early retirements begin—some French entries falter, mechanical parts failing under strain.

Hour 2 (6:00 PM) — Sparks and Flames

The pace is brutal. In the pits, mechanics pour over wires, tighten bolts, change tires. But disaster strikes: Brisson’s Stutz, after fueling, erupts in flames. Fire engulfs the rear before he can bring it to a halt. He escapes, shaken. His car, however, is scorched and limps away later with repairs. The damage is done. The Bentleys press on.

Hours 3–4 (7:00 – 8:00 PM) — The Bentley Phalanx

By dusk, four Bentleys dominate the top slots. Their mechanics work like clockwork, pit stops snappy; driver changes seamless. The Stutz press, but is increasingly fragile. Non-Bentley contenders vanish one by one under mechanical stress. The green cars carry the day.

Hours 5–8 (8:00 PM – Midnight) — Into the Gloom

Night falls. Headlights slice through fog and spray. The Bentleys pick off lap after lap, the field thinning rapidly. Kidston and Dunfee slip back momentarily for bulb and wiring repairs; Benjafield’s car leaks water. But the formation presses on, their rhythm relentless. The Stutz slows further; its exhaustion evident.

Hours 9–12 (Midnight – 3:00 AM) — The Long, Dark Gauntlet

The pit signals are quiet; the leaders are steady. Clement’s Bentley, though delayed earlier, pushes now to regain time. The competitor field is skeletal. Some cars crawl by with broken parts; others vanish forever. The Bentleys, though, remain smooth, unbroken.

Hours 13–16 (3:00 – 6:00 AM) — Fading Shadows

Through the darkest hours, the green phalanx keeps its course. Birkin and Barnato remain out front, unshaken. Others rotate, drivers rest and revive. The track is rough, unforgiving, but their machines endure. The chase from Chrysler and Stutz is now distant and fading.

Hours 17–20 (6:00 – 9:00 AM) — Dawn’s Triumph

The sky brightens. The Bentleys’ lead is commanding. The surviving challengers strain in vain, their pace hollowed by wear. Birkin, Barnato, Clement carve circuits like history; Kidston, Benjafield keep formation. The task isn’t to win—it's to finish. And they will.

Hours 21–23 (9:00 – 11:00 AM) — The Final March

With only hours left, the team management signals for formation finish. One by one, the Bentleys glide in behind their leader, engines purring, mechanical spirits intact. Behind them, the field is diminished. The challengers’ fight is over. The green machines, battered but undefeated, bear down.

Hour 24 (11:00 AM – Noon) — The Sweep Is Complete

As the 24 hours expire, the four Bentleys cross the line in formation. Birkin & Barnato lead the pack, followed by Kidston/Dunfee, Benjafield/d’Erlanger, Clement/Chassagne. The crowd erupts at this display of dominance: a complete 1–2–3–4 by one team, the first such sweep in Le Mans history.

Aftermath & Results

Winners: Woolf Barnato / Sir Henry “Tim” Birkin — Bentley Speed Six

Distance: 2,843.83 km

Average Speed: 118.49 km/h

Second: Glen Kidston / Jack Dunfee — Bentley 4½ Litre

Third: Dudley Benjafield / Baron André d’Erlanger — Bentley 4½ Litre

Fourth: Frank Clement / Jean Chassagne — Bentley 4½ Litre

Fastest Lap: Sir Henry “Tim” Birkin — 7m21s (~133.55 km/h)

Notables:

This was Bentley’s most dominant Le Mans performance yet, unmatched in its era. racingsportscars.com+3Wikipedia+3sportscars.tv+3

The sweep of the first four finishing positions underlined the strength of the works program and the mechanical resilience of the Speed Six. radiolemans.co+4Wikipedia+4sportscars.tv+4

The Stutz, once a fierce rival, succumbed to fire and mechanical exhaustion. Wikipedia+2sportscars.tv+2

Half the field retired by dawn, unable to match the endurance or reliability of the Bentleys. sportscars.tv+224h-lemans.com+2

1930 — Speed, Risk, and the Last of the Speed Sixes

Hour 0 (4:00 PM) — Into the Heat

The sun blazes over Sarthe. Only 18 cars take the start, the smallest field in Le Mans history. Yet the challenge ahead is vast. Mercedes enters with a fearsome 7.1 L SSK supercharged machine, piloted by Rudolf Caracciola and Christian Werner. Bentley, defending its dominance, fields three Speed Sixes and three “Blower” Bentleys. Among the mix is the first-ever all-female pairing: Odette Siko and Marguerite Mareuse in a Bugatti Type 40.

The roar is instantaneous. Caracciola’s Mercedes streaks ahead on the Mulsanne Straight. Birkin’s Blower Bentley pursues with ferocity, closing the gap. The race, as ever, begins as a duel of nerve and metal.

Hour 1 (5:00 PM) — Lap Records and Early Warnings

Caracciola sets a blistering pace, breaking off the supercharger to conserve fuel. Birkin responds, tearing around the lap in 6′52″, then pushing to 6′48″ and overtaking the Mercedes under braking at Mulsanne. The field reels. But the strain shows: Birkin’s rear tyre blows; he pits, changes, and storms back to the chase. It’s a warning: speed invites disaster.

Hours 2–3 (6:00–7:00 PM) — Swaps and Strategy

The leading cars swap position as tyres, fuel, and strategy play out. Birkin’s second tyre blows, forcing yet another stop. Meanwhile, Barnato and Kidston in the “works” Speed Six maintain measured pace, avoiding extremes. The Mercedes fights on, strong but not invulnerable. Off in lower classes, Talbots and small-engine cars work their own battles with reliability, plugs, fuel mixes, and overheating.

Hours 4–8 (8:00 PM – Midnight) — Night Encroaches on the Trail

By nightfall, the Mercedes and Bentleys duel under lamps and moonlit roads. The Mercedes, despite its early vigor, begins to slow—dynamo trouble, flickering lights, weakening battery. Around 1:30 am, Caracciola’s light dims and intervals grow. He limps into the pits; a wire from the dynamo has come loose. The battery dies. His bid ends. The Bentleys, now unchallenged, press on through the darkness in formation.

Hours 9–16 (Midnight – 6:00 AM) — The Quiet March

With the Mercedes gone, the Bentleys take command. The works Speed Sixes lead, their pace steady, smooth, disciplined. The Blower Bentleys, heavy and understeering, begin to slip behind. In the small classes, the Talbot AO90 earns respect for staying alive. The women’s Bugatti, Siko / Mareuse, drives faultlessly, quietly threading her way toward finish.

In the dead of night, fewer than half the starters remain in motion. Pit stops are efficient and silent; drivers rest briefly, then return to their machines grim-faced. Every lap is an affirmation of endurance over bravado.

Hours 17–20 (6:00 – 9:00 AM) — Dawn’s Preservation

The sky lightens. The leading Bentleys maintain a safe margin. The pace slows slightly—not for fatigue, but for calculation. The “Blowers” lag, their extra weight and complexity taking toll. Behind them, Talbots, Bugattis, Tractas fight for class honors. But the distance to the top is already stretching.

Hours 21–23 (9:00 – 11:00 AM) — Safeguarding the Finish

In these final hours, strategy transforms into survival. The leading Bentleys run almost in formation, only servicing for essentials. Any mechanical quirk now risks everything. The Bugatti women, still on the move, attract admiration as they close in on small-car distance targets. But the spotlight stays on the green machines ahead.

Hour 24 (11:00 AM – Noon) — Victory and Legacy

As the clock strikes noon, the Speed Six of Woolf Barnato / Glen Kidston crosses the line. Behind them, the other works Bentley follows; the Blowers limp home where they can. The strategy — consistency, caution, endurance — has beaten the flash and risk.

The Bugatti pairing Siko / Mareuse finishes seventh overall — a moral triumph as much as a technical one, their all-female entry earning quiet nods of respect.

Thus ends 1930: the last great victory for Bentley’s Speed Six, a testament to the old guard before rapid change would sweep through Le Mans in the 1930s.

Aftermath & Results

Winners: Woolf Barnato / Glen Kidston — Bentley Speed Six

Distance: 2,930.66 km

Average Speed: 122.111 km/h

Second: Frank Clement / Dick Watney — Bentley Speed Six

Third: Brian Lewis / Baron Essendon / Hugh Eaton — Talbot AO90

Other class winners / notes:

The “Blower” Bentleys all failed to finish (mechanical failure).

The Talbot AO90 claimed class victory in 3.0 L class.

Odette Siko / Marguerite Mareuse, in their Bugatti, became the first all-female team to complete Le Mans, finishing 7th overall.

Fastest Lap: Henry Birkin — 6′48″ (~144.36 km/h)

Sources

“1930 24 Hours of Le Mans” — Wikipedia en.wikipedia.org

Motorsports Database / Magazine — 1930 race report & results motorsportmagazine.com

RacingSportsCars.com — 1930 Le Mans results racingsportscars.com

24h-en-piste.com — official 1930 results listing 24h-en-piste.com

RadioLeMans / Charles Dresser history — “1930: speed and endurance” radiolemans.co

24h-lemans.com — Bentley success in the era 1924–1930 24h-lemans.com

Experience LeMans — competitor & event summary 1930 experiencelemans.com

1931 — The End of the Bentley Era

Hour 0 (4:00 PM) — Shadows Over the Empire

The air is heavy with change. Bentley, once untouchable, arrives at Le Mans uncertain. W.O. Bentley himself is gone from the company, and its finances hang by a thread. The familiar forest-green cars return — two 4-Litre and one 8-Litre — but they feel like relics of a fading empire.

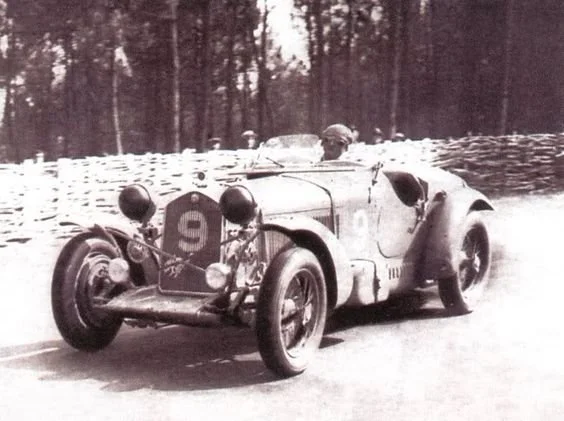

Across the paddock, Alfa Romeo has arrived. Sleek red 8C 2300s, lighter, faster, and thoroughly modern. Drivers Luigi Chinetti and Henry Birkin — yes, the same Birkin who made his name with Bentley — now wear Italian colors. On the grid, Scuderia Ferrari men hover quietly, adjusting goggles and grins. The tide is shifting.

The tricolor falls. Forty-six cars leap into motion, engines roaring into the warm June air. Dust billows across the Mulsanne. The era of unchallenged Bentley dominance ends here — though no one yet knows it.

Hour 1 (5:00 PM) — Red vs Green

The first hour is a clash of philosophies. The heavy Bentleys thunder down the straights, their torque immense. But the nimble Alfas slice through corners like scalpels, lighter on tires, quicker to brake. Birkin’s 8C trades the lead with Howe’s Bentley; neither concedes.

Behind them, Talbot, Delage, and Bugatti fight in their own battles — elegance and reliability over raw speed.

Hours 2–3 (6:00–7:00 PM) — The Duel Intensifies

As the evening sun slants low, the Bentleys begin to sweat. Their massive engines devour fuel, forcing frequent stops. Alfa Romeo, meanwhile, sips fuel carefully. Chinetti and Birkin manage their pace, alternating between attack and restraint.

By 7 PM, the Italian cars lead. The green giants follow, grumbling and overheating.

Hours 4–8 (8:00 PM – Midnight) — The Night Descends

Dusk brings a violet glow over the circuit. The air cools, but the race grows hotter. Bentley’s 8-Litre, immense and beautiful, suffers mechanical woe — clutch fade, oil leaks, cooling problems. One car limps to the pits, another withdraws entirely before midnight.

The Alfas, by contrast, glide through the darkness. Their small headlights dart through corners like fireflies. Birkin and Howe exchange leads, the former driving for Italy, the latter for England. The symbolism isn’t lost on the crowd.

Hours 9–12 (Midnight – 3:00 AM) — Silence and Attrition

The night is merciless. By midnight, nearly half the field is gone. Cars sit at odd angles on the grass, hoods open, engines spent. The noise softens to a hum, interrupted by the occasional burst of an Alfa Romeo’s straight-eight howl.

Birkin, once Bentley’s pride, now leads in the scarlet 8C 2300. His rhythm is flawless — fast, fearless, fluid. Howe, pushing his Bentley too hard, feels it begin to falter.

Hours 13–16 (3:00 – 6:00 AM) — Dawn’s Edge

Morning mists rise from the low fields. The Alfas still dominate. Howe’s Bentley limps into the pits, water pouring from its seams. Its crew works desperately, but the damage is terminal.

The spectators awaken to see the red cars leading by vast margins. The only challenge comes from Bugatti, quick but inconsistent, and a plucky OM from Italy.

Hours 17–20 (6:00 – 9:00 AM) — The Art of Survival

As sunlight returns, the Alfas shift from attack to preservation. Chinetti drives like a metronome — smooth, precise, conserving every moving part. His co-driver, Lord Howe, mirrors the rhythm. In this era before team radios, they communicate through instinct and hand signals at the pit wall.

Bentley’s last surviving entry soldiers on in the lower ranks — an honorable but hollow end to a dynasty.

Hours 21–23 (9:00 – 11:00 AM) — The Race Belongs to Milan

The lead Alfa continues without error. Only a mechanical fluke could stop it now. The crowd, sensing inevitability, flocks toward the grandstand. Pit boards wave calm instructions: “NO RISK.”

Behind, a pair of Talbots and Bugattis fight gallantly for minor places. It’s clear: the age of brute strength is over. Precision and lightness are the new kings.

Hour 24 (11:00 AM – Noon) — The Red Victory

The clock strikes noon, and the crowd erupts as the red Alfa Romeo crosses the finish line. Chinetti and Howe embrace beneath the tricolor. The Bentley era is over — the Italians have claimed the crown.

The Alfas finish one-two, both 8C 2300s running flawlessly, completing over 3,000 km at an average speed never before seen. Where Bentley’s thunder once echoed, now a new song hums: the symphony of speed, control, and engineering elegance.

Aftermath & Results

Winners: Lord Howe / Sir Henry “Tim” Birkin — Alfa Romeo 8C 2300 LM

Distance: 3,017.65 km

Average Speed: 125.35 km/h

Second: Boris Ivanowski / Henri Stoffel — Alfa Romeo 8C 2300 LM

Third: De Maleplane / Melleville — Talbot AO90

Fastest Lap: Henry Birkin — 7m03s (≈139 km/h)

Notes:

This was Alfa Romeo’s first Le Mans victory — and the beginning of its four-year domination.

It was also the last appearance of the factory Bentleys, as financial collapse forced W.O. Bentley’s company into receivership later that year.

The partnership between Alfa Romeo and Scuderia Ferrari began to blossom here — the seed of an empire that would dominate motorsport for decades.

The victory of Lord Howe and Birkin was poetic: a British noble and a former Bentley hero leading Italy to triumph.

Sources

Automobile Club de l’Ouest (ACO) — Official 1931 24 Heures du Mans Records

24h-lemans.com — “1931: Alfa Romeo’s First Triumph”

Motorsport Magazine — “Le Mans 1931 Race Report,” July 1931 Issue

RacingSportsCars.com — Complete Results Database

Wikipedia — 1931 24 Hours of Le Mans

Goodwood Road & Racing — “When Birkin Went Red: How Alfa Dethroned Bentley”

1932 — The Dawn of the Modern Le Mans

Hour 0 (4:00 PM) — A New Circuit, A New Era

The 24 Hours of Le Mans returns to a transformed stage. The ACO has shortened the course to 13.492 km by removing the perilous stretch through Pontlieue and adding a new right-hand link from Tertre Rouge directly to Maison Blanche. It’s smoother, faster, and for the first time includes permanent pit structures — a glimpse of the race’s future.

Thirty-three machines line the start under blazing sun. The red Alfa Romeo 8C 2300s stand poised at the front — sleek, low, and purposeful — defending their 1931 crown. Their opposition is a patchwork of Bugattis, Talbots, and Rileys, plus the valiant but aging Aston Martin and OM entries.

At the drop of the tricolour, engines shriek and the field charges away. Dust plumes rise, echoing across the Sarthe valley. The modern era of Le Mans has begun.

Hour 1 (5:00 PM) — Alfa Ascendant

Within the first laps, the Alfas make their statement. Raymond Sommer, partnered with Luigi Chinetti, takes an early lead — their 8C slicing through traffic with surgical precision. Behind them, the sister Alfa of Franco Cortese and Tazio Nuvolari (the “Flying Mantuan”) keeps close, its exhaust crackle like machine-gun fire.

The Bugattis fight bravely but can’t match the Alfas’ composure through Maison Blanche. By the first pit cycle, the Italians have built a minute’s cushion.

Hours 2–3 (6:00–7:00 PM) — French Resilience

The Talbots and Delahayes press on, slower but unyielding. The French crowds cheer each local hero who roars past. Yet the Italian cars dominate the air — their twin-cam eights smooth and sonorous.

At the three-hour mark, the first mechanical retirements arrive: oil leaks, misfiring magnetos, a shattered half-shaft. The heat takes its toll.

Hours 4–8 (8:00 PM – Midnight) — Into the Night

Darkness descends over the new circuit. Headlamps swing wide through the high-speed Maison Blanche curve, now more dangerous for its added speed. Sommer and Chinetti continue their rhythm — precise, unflinching.

Nuvolari, in the second Alfa, begins to push. The crowd senses the duel building between teammates: raw aggression versus cool calculation. Bugatti No. 44 falls back with engine troubles, and the field thins by half.

Hours 9–12 (Midnight – 3:00 AM) — Rain and Firelight

A fine rain sweeps across Sarthe. The course gleams under headlamps. The Alfas slow slightly but remain unchallenged. Talbot and Aston Martin pick their way through puddles, engines hissing.

At 2 AM, Sommer pits for tires and coffee, still leading. The crew’s efficiency borders on art. Each second gained in the pit is another lap on the road.

Hours 13–16 (3:00 – 6:00 AM) — The Chase That Wasn’t

Before dawn, the second Alfa begins to fade. Nuvolari’s ferocity has cost him — a failing brake cylinder, a slipping clutch. Sommer, meanwhile, glides through the gloom, his car whispering along the straights as others thunder and cough.

By sunrise, his lead exceeds five laps. The red car seems unbreakable.

Hours 17–20 (6:00 – 9:00 AM) — Daylight Dominion

Morning brings calm. The rain clears. Spectators return to the fences, picnic baskets in hand, watching the crimson machines flash by like clockwork. Sommer and Chinetti maintain perfect balance — never over-revving, never gambling.

The remaining Bugattis trail, valiant but beaten by modernity. The French crowd cheers them anyway.

Hours 21–23 (9:00 – 11:00 AM) — Preservation Over Pace

The final hours are measured and controlled. Sommer keeps the revs low, Chinetti counting each lap with precision. Mechanics at pit wall exchange nods — the car’s heartbeat steady, oil pressure perfect. Only catastrophe could stop them now.

Hour 24 (11:00 AM – Noon) — A Red Dawn Victorious

At exactly noon, the red Alfa Romeo 8C 2300 LM crosses the finish line, unchallenged. The crowd surges forward. Sommer and Chinetti, drenched in oil and exhaustion, shake hands atop their car. Behind them, another Alfa finishes second, sealing a one-two repeat for Italy.

For the first time in history, a car has averaged more than 125 km/h over 24 hours. The modern era of endurance racing has truly arrived.

Aftermath & Results

Winners: Raymond Sommer / Luigi Chinetti — Alfa Romeo 8C 2300 LM

Distance: 2 960.08 km

Average Speed: 123.41 km/h

Second: Tazio Nuvolari / Franco Cortese — Alfa Romeo 8C 2300 LM

Third: Luce / de Maleplane — Talbot AO90

Fastest Lap: Raymond Sommer — 6′33″ (~136 km/h)

Notes:

This was Alfa Romeo’s second consecutive win, confirming the 8C 2300 as the car to beat.

The new circuit layout, faster and safer, established the modern rhythm of Le Mans.

Luigi Chinetti’s calm endurance and Sommer’s relentless pace became the blueprint for professional endurance teamwork.

Bentley did not return; their factory had fallen silent the year before. The new world belonged to Milan.

Sources

Automobile Club de l’Ouest (ACO) — Official 1932 24 Heures du Mans Records

24h-lemans.com — “1932: The New Circuit and Alfa’s Dominance”

Motorsport Magazine — July 1932 Issue Race Report

RacingSportsCars.com — 1932 Results Database

Goodwood Road & Racing — “Sommer & Chinetti: The Men Who Perfected Endurance”

Wikipedia — 1932 24 Hours of Le Mans

1933 — The Reign of Red and Rain

Hour 0 (4:00 PM) — Heat, Dust, and the Roar of Tradition

The June afternoon shimmers with heat as the tricolor falls. Thirty-three starters launch forward, the air alive with the sound of supercharged engines. The red Alfa Romeo 8C 2300s lead the charge, chasing their third consecutive victory.

In the front row: Raymond Sommer and Tazio Nuvolari, both titans. Luigi Chinetti and Philippe Varent take the second Alfa, while French challengers from Bugatti, Talbot, and Delahaye line up behind. Aston Martin fields a pair of green DB2s — brave, if outmatched.

Within minutes, the Alfas thunder ahead, their long hoods slicing through sunlight and haze. Behind them, the rest of the field fights to breathe their dust.

Hour 1 (5:00 PM) — The Red Train

Sommer takes the lead immediately, his Alfa running smooth, the straight-eight singing. Nuvolari follows, stalking his teammate, waiting for weakness. Bugatti’s Jean Gaupillat pushes hard in pursuit but overdrives early, and his car begins to fade.

By the end of the first hour, the Alfas are one-two. The rest fight merely for survival.

Hours 2–3 (6:00–7:00 PM) — The Duel Begins

Nuvolari cannot wait. The fiery Mantuan dives past Sommer through Maison Blanche in a move few dare to try. The crowd gasps; the teammates trade the lead back and forth like prizefighters. For the next two hours, the red cars duel at terrifying pace, each lap faster than the last. Their pit crews beg restraint. Neither listens.

Hours 4–8 (8:00 PM – Midnight) — Darkness and Disaster

As night falls, the duel continues into madness. Flames from exhausts lick the rain-specked air. The lead Alfas trade seconds under the stars. Then, just before midnight, disaster strikes: Sommer’s Alfa hits a patch of oil and spins at Arnage. The car slides into the ditch but miraculously avoids destruction. He limps back to the pits, mud-splattered but running.

Nuvolari seizes the lead — but even his machine shows signs of strain. A clutch groans, the gearbox howls. Rain begins to fall.

Hours 9–12 (Midnight – 3:00 AM) — The Rain Arrives

The storm hits hard. Sheets of water drench the circuit, and the drivers wrestle their cars through the darkness. Headlights reflect off standing water, blinding and deadly. Many cars skid out — Talbots, MGs, and even the mighty Delahaye 138s aquaplane off the road.

Nuvolari’s Alfa powers through the torrent like a red ghost, tires cutting arcs through the rain. Behind, Sommer claws back ground, refusing to yield.

Hours 13–16 (3:00 – 6:00 AM) — The Bleeding Dawn

By dawn, the rain softens to mist. The Alfas remain first and second, but their pace has punished them. Sommer’s radiator leaks. Nuvolari’s clutch threatens failure. Mechanics work with quiet urgency, wrapping tools in rags to keep them from slipping in their wet hands.

In the lower classes, the French machines — Bugattis and Talbots — soldier on, battered but proud. The British Lagondas and Aston Martins fade into attrition.

Hours 17–20 (6:00 – 9:00 AM) — Blood and Precision

With daylight comes renewed aggression. Sommer drives with a surgeon’s touch, balancing speed and preservation. Nuvolari, by contrast, attacks relentlessly, shaving seconds per lap even as his clutch slips.

The Alfas run so hard that their nearest rival — a Bugatti T50 — is more than 20 laps behind. The only threat now is themselves.

Hours 21–23 (9:00 – 11:00 AM) — Exhaustion and Triumph

The final hours blur into endurance. Sommer’s Alfa develops a misfire but continues. Nuvolari’s clutch holds — barely. The rain returns intermittently, coating the track in treachery.

Spectators cheer every pass, aware they are witnessing the peak of Italian mastery. No car since the Bentleys has shown such dominance.

Hour 24 (11:00 AM – Noon) — Victory in Scarlet

At the stroke of noon, the checkered flag waves. The red Alfa Romeo 8C 2300 of Tazio Nuvolari and Raymond Sommer crosses first — victorious yet exhausted. Their duel has become legend: ruthless, passionate, and entirely victorious.

The sister Alfa, driven by Chinetti and Varent, finishes second. Bugatti’s T50 fills the final podium slot, brave but distant.

As the rain subsides, the two winning drivers — soaked, mud-streaked, and smiling — shake hands on the pit wall. Le Mans 1933 belongs to Alfa Romeo, to the 8C 2300, and to two men who refused to drive like mortals.

Aftermath & Results

Winners: Tazio Nuvolari / Raymond Sommer — Alfa Romeo 8C 2300 LM

Distance: 3,145.16 km

Average Speed: 130.32 km/h

Second: Luigi Chinetti / Philippe Varent — Alfa Romeo 8C 2300 LM

Third: Jean Gaupillat / Louis Trintignant — Bugatti T50

Fastest Lap: Tazio Nuvolari — 6′03″ (~144 km/h)

Notes:

This marked Alfa Romeo’s third consecutive victory, cementing the 8C 2300 as the definitive endurance car of the era.

The internal duel between Sommer and Nuvolari became one of Le Mans’ great legends — an early echo of future teammate rivalries.

Rain and attrition claimed more than half the field, but the Alfas never faltered mechanically.

By 1933, Le Mans had transformed into a proving ground for national pride — a test of industrial endurance as much as human will.

Sources

Automobile Club de l’Ouest (ACO) — Official 1933 24 Heures du Mans Records

24h-lemans.com — “1933: The Duel in the Rain”

Motorsport Magazine — July 1933 Race Report

RacingSportsCars.com — 1933 Results Database

Goodwood Road & Racing — “Nuvolari and Sommer: The Rivalry That Defined a Generation”

Wikipedia — 1933 24 Hours of Le Mans

1934 — The Last Dance of the Alfas

Hour 0 (4:00 PM) — Clouds Over Le Mans

The start of the 1934 24 Hours feels different. The confident roar of Alfa Romeo still echoes down the Mulsanne, but the mood is uneasy. The once-invincible 8C 2300s return — yet without the same factory presence. Scuderia Ferrari, now running the works cars on behalf of Alfa, sends two scarlet entries.

Across the grid, the field has grown to forty-two starters. Among them: Lagonda, MG, Riley, Aston Martin, and a new French force in the nimble blue Delahayes. The sky looms grey and unsettled. The air is cool. It feels like the dawn of something new — and the twilight of something great.

The tricolor falls. Engines bellow. Drivers sprint across the tarmac and leap into cockpits. Another Le Mans begins.

Hour 1 (5:00 PM) — Early Balance of Power

The Alfas immediately assert themselves. The car of Luigi Chinetti and Philippe Varent surges into the lead, with Sommer and Benoist close behind in the second Ferrari-run machine. Behind them, the British Rileys and Lagondas snap at the tailpipes, lighter and nimbler through the corners, though lacking in raw pace.

Already, the Bugattis struggle — too fragile for the pounding Sarthe straights. The Talbots, too, begin to fade early. By the end of the first hour, it’s a familiar sight: Alfa at the front, red and relentless.

Hours 2–3 (6:00–7:00 PM) — A New Challenger Emerges

Rain spits from the clouds, then steadies into a light drizzle. The British teams thrive in it. The Riley Ulsters — small, tidy, and beautifully balanced — begin to claw their way up the order. The Lagondas, heavy but indestructible, lurk nearby.

At the front, Sommer’s Alfa leads, but Chinetti’s is nursing fuel starvation issues. Mechanics scramble with funnels and rags, a reminder that even Italian precision can falter under French rain.

Hours 4–8 (8:00 PM – Midnight) — The Night Beckons

As darkness falls, the race finds its rhythm. Sommer and Benoist stretch their lead to a commanding five laps. Behind, Rileys, Aston Martins, and Delahayes trade places with quiet fury.

Then, just before midnight, calamity: Sommer’s leading Alfa pulls into the pits trailing a faint mist of oil. The mechanics swarm it, tightening, topping, sealing — but it’s terminal. A cracked oil tank ends their bid. Sommer climbs out in silence. The pit lane, for years ruled by his machine, feels suddenly empty.

Chinetti’s Alfa inherits the lead, limping slightly from its earlier fuel woes.

Hours 9–12 (Midnight – 3:00 AM) — The Rain Returns

By midnight, the rain returns in earnest, and with it chaos. One Lagonda spins off near Arnage, losing half an hour. A Bugatti collides with a Talbot in the dark, both destroyed. The Rileys, however, thrive in the slick. Their balance, lightness, and sure-footedness keep them alive while heavier cars struggle.

Chinetti and Varent nurse the surviving Alfa carefully. The lead shrinks, but the car still runs strong.

Hours 13–16 (3:00 – 6:00 AM) — Dawn of Doubt

Morning comes with pale light and ground fog. The Alfa’s lead remains — but the British cars are closing. The Rileys lap faster, their 1½-litre engines running clean and consistent. The Aston Martin Ulster of Charles Martin and Maurice Falkner rises through the order.

Chinetti’s Alfa begins to sputter again. Fuel feed problems worsen; misfires echo through the pit straight. Mechanics fix what they can — but the car is no longer perfect.

Hours 17–20 (6:00 – 9:00 AM) — The British Charge

The Rileys, one by one, move up the leaderboard. The little blue-and-white cars run like clockwork, clicking off laps with mathematical precision. The crowd senses a possible upset.

At 8:30 AM, the leading Alfa pits for a long stop. Fuel lines are cleared, spark plugs replaced. It loses nearly two laps. When it re-joins, the top three are separated by mere minutes: Alfa, Riley, Aston.

Hours 21–23 (9:00 – 11:00 AM) — Hanging On

The rain stops, leaving the track slick and treacherous. The Riley No. 27 closes the gap to one lap, but its drivers know they dare not push harder — the Alfa still has speed in reserve. Chinetti coaxes his wounded machine through each sector like a shepherd guiding a tired horse.

The crowd stands now, silent between the rumbles. The next mistake could decide the race.

Hour 24 (11:00 AM – Noon) — The Final Lap of the Red Empire

As noon strikes, the red Alfa Romeo of Luigi Chinetti and Philippe Varent takes the flag — weary but victorious. The once-dominant marque has won again, but this time by survival, not supremacy.

The British Rileys finish second and third, having proven their mettle and reliability. Their smaller engines may not have won the war, but they’ve shown what the next generation of endurance machines will look like.

The crowd’s cheers are respectful, not raucous. Le Mans 1934 is remembered not for domination — but for the passing of an era.

Aftermath & Results

Winners: Luigi Chinetti / Philippe Varent — Alfa Romeo 8C 2300 LM (Scuderia Ferrari)

Distance: 3,049.19 km

Average Speed: 127.04 km/h

Second: Percy Maclure / Cyril Paul — Riley Ulster Imp

Third: Freddie Dixon / Charlie Dodson — Riley Nine

Fastest Lap: Raymond Sommer (Alfa Romeo) — 6′12″ (~142 km/h)

Notes:

Alfa Romeo claimed its fourth consecutive Le Mans victory, all with variants of the 8C 2300.

Scuderia Ferrari officially ran the team for Alfa, marking Enzo Ferrari’s first Le Mans victory as entrant.

The Rileys’ 2–3 finish heralded a new age of precision engineering and endurance discipline.

1934 is remembered as the last true chapter of the “Alfa dynasty” before the rise of Lagonda, Delahaye, and Bugatti in the late 1930s.

Sources

Automobile Club de l’Ouest (ACO) — Official 1934 24 Heures du Mans Records

24h-lemans.com — “1934: Scuderia Ferrari’s First Le Mans Triumph”

Motorsport Magazine Archive — July 1934 Race Report

RacingSportsCars.com — Full 1934 Entry & Results List

Goodwood Road & Racing — “When Alfa’s Reign Began to Fade”

Wikipedia — 1934 24 Hours of Le Mans

1935 — The Fall of Alfa, the Rise of Lagonda

Hour 0 (4:00 PM) — Storm in the Air

Grey clouds hang over the Sarthe circuit as thirty-eight cars line the grid. The once-dominant red Alfa Romeos of Scuderia Ferrari are here again — two 8C 2300s, smooth and purposeful — but the aura of invincibility has faded. Across from them stands a new breed of challengers: the Lagonda M45 Rapide, Aston Martins, Rileys, Delahayes, and a handful of Bugattis hungry to end Italy’s reign.

The tricolor drops. Drivers sprint across the slick tarmac, leap into cockpits, and twist ignitions. Engines roar. Tyres spit water. The 13.49 km circuit awakens to a howl of thunder and gasoline.

Hour 1 (5:00 PM) — Red at the Front, Grey on the Horizon

The opening laps look familiar — the Alfas lead confidently, their engines smooth and their pace commanding. Behind them, the Lagondas and Rileys settle into rhythm, biding their time. But the weather has other plans. A sudden shower drenches the track. Within minutes, visibility collapses. Cars slither through Arnage and Mulsanne like shadows on glass.

Sommer and Chinetti in the lead Alfa back off slightly, unwilling to gamble. The Lagonda of Johnny Hindmarsh and Luis Fontés, running in fourth, seems to come alive in the wet — its heavy chassis now a virtue rather than a flaw.

Hours 2–3 (6:00–7:00 PM) — The Race Tightens

As the rain steadies, attrition begins. Two Bugattis spin out at Maison Blanche; one catches fire. The small-engine MGs fall victim to misfires. But the Lagonda presses forward — Hindmarsh’s smooth hands keeping the big British car planted while others flounder. By dusk, it runs second behind the Alfas.

Hours 4–8 (8:00 PM – Midnight) — Darkness Descends

The rain returns, heavier now, and with it chaos. Lightning flashes beyond the trees. The red Alfas, their lamps cutting arcs of gold through the storm, remain fast but restless. The pit boards read “SLOW” — an order few heed.

Near midnight, fate intervenes: one of the Ferraris slows, smoke trailing. A cracked fuel line. Mechanics scramble in vain; the leak proves fatal. Only one Alfa remains, the Chinetti/Sommer car, holding a fragile lead.

Behind it, the Lagonda runs flawlessly. Its drivers — methodical, calm — share brief nods at every changeover. They are driving not to chase, but to outlast.

Hours 9–12 (Midnight – 3:00 AM) — The Long Vigil

Through the soaked night, the Lagonda keeps steady. The Alfas, lighter but more temperamental, begin to struggle with clutch wear and electrical gremlins. A Riley retires with gearbox failure. Another Bugatti hydroplanes into a barrier.

At 2 AM, Hindmarsh pits for oil and tyres. Fontés climbs in, visor dripping, and disappears into the dark. The car’s six-cylinder engine hums evenly, every note a promise of survival.

Hours 13–16 (3:00 – 6:00 AM) — Dawn and Determination

The first light of morning cuts through mist. Only fifteen cars remain. The leading Alfa still holds a small edge, but its engine note grows uneven. Mechanics whisper of valve trouble. The Lagonda, unhurried, closes the gap with mechanical precision.

At 5 AM, Sommer pits, his car coughing. The Lagonda passes, taking the lead as the sun breaks through the cloud. The crowd erupts — Britain leads Le Mans again.

Hours 17–20 (6:00 – 9:00 AM) — Sunshine and Strategy

The rain stops, and the circuit begins to dry. Fontés and Hindmarsh settle into a disciplined pace, protecting their advantage. The Alfas try to respond, but it’s too late; reliability, not raw speed, has decided the day. The Lagonda glides past the pits, its dark green paint glistening. Every lap strengthens its place in history.

Hours 21–23 (9:00 – 11:00 AM) — The Final Test

The last hours are tense. The Lagonda’s clutch starts to slip, its brakes fade, and its drivers nurse it carefully. The Alfa Romeo, still gallant in defeat, continues in second — a champion conceding its crown with dignity.

The crowd, sensing the inevitable, crowds the railings. Britain is about to reclaim Le Mans for the first time since 1930.

Hour 24 (11:00 AM – Noon) — Victory for the Isles

At high noon, under clearing skies, the dark green Lagonda M45 Rapide crosses the line. Fontés raises a hand, Hindmarsh waves the Union Jack from the pit wall. After four years of Italian rule, Le Mans is British once more.

The Alfa Romeo follows several laps down — valiant but beaten by a heavier, steadier rival. The survivors limp home behind them: Rileys, Astons, Delahayes. The age of roaring red Alfas ends, and the quiet, enduring heart of British endurance begins.

Aftermath & Results

Winners: Johnny Hindmarsh / Luis Fontés — Lagonda M45 Rapide

Distance: 2,987.05 km

Average Speed: 124.46 km/h

Second: Raymond Sommer / Luigi Chinetti — Alfa Romeo 8C 2300

Third: Charles Brackenbury / Maurice Falkner — Aston Martin Ulster

Fastest Lap: Raymond Sommer — 6′20″ (~139 km/h)

Notes:

Lagonda’s victory was the first all-British win since 1930, and its only overall Le Mans triumph.

The race was plagued by rain and accidents, leaving barely half the field classified.

It marked the symbolic end of Alfa Romeo’s dominance; Ferrari’s privateer effort would soon focus elsewhere.

The victory revitalized British interest in endurance racing and set the stage for Aston Martin’s postwar rise.

Sources

Automobile Club de l’Ouest (ACO) — Official 1935 24 Heures du Mans Records

24h-lemans.com — “1935: Lagonda’s Lone Triumph”

Motorsport Magazine — July 1935 Issue Race Report

RacingSportsCars.com — Full 1935 Results Database

Goodwood Road & Racing — “When Lagonda Dethroned Alfa Romeo”

Wikipedia — 1935 24 Hours of Le Mans

1937 — France Strikes Back

Hour 0 (4:00 PM) — Return of the 24 Hours

A year’s silence has hung over Le Mans. The 1936 race was lost to labor strikes and unrest, but now, in June 1937, the grandstands hum again. The air smells of fuel, wet tarmac, and anticipation. The tricolor drops; forty-three cars leap forward into motion.

Gone are the roaring Bentleys and the imperious Alfas. In their place stands a new generation of French machinery — Bugatti, Talbot, Delahaye — eager to reclaim home glory. Germany, too, has arrived, sending powerful BMW 328s that whisper of the precision to come. Britain fields its usual mix of Rileys, Lagondas, and MGs, noble if out-gunned.

At the head of the grid sits a dark blue Bugatti 57G “Tank,” driven by Jean-Pierre Wimille and Robert Benoist — its aerodynamic shape alien amid the upright pre-war racers. As the flag falls, the crowd senses change. The era of brute force is ending; the age of streamlining has begun.

Hour 1 (5:00 PM) — The Blue Machines Surge

The Bugatti Tanks immediately dominate. Wimille storms through the first laps, his car’s enclosed bodywork slicing through the air while others wrestle drag and turbulence. The Talbots and Delahayes try to respond, but the Bugatti’s pace is untouchable.

Behind them, the German BMWs run neatly, their inline-sixes humming with quiet precision. The British Rileys play a conservative game, running steady in the midfield — a lesson learned from years of attrition.

Hours 2–3 (6:00–7:00 PM) — Rain and Attrition

Rain arrives by the third hour, turning the circuit into a mirror. Cars dance and slide through Arnage and Maison Blanche. A Delahaye spins into the ditch, a Talbot retires with clutch failure, and one of the Bugatti “Tanks” pits with electrical gremlins.

But Wimille’s car, #2, presses on — calm, unflinching. He drives with the precision of a surgeon, placing the car exactly where the grip remains. By nightfall, he and Benoist lead comfortably.

Hours 4–8 (8:00 PM – Midnight) — Night of the Tanks

As darkness falls, the Bugatti’s advantage grows. Its streamlined shell and improved headlights make it nearly unbeatable on the straights. The only real rival is another Bugatti, the #3 car of Labric and Brivio, but it too begins to suffer minor gearbox trouble.

In the pits, engineers work by lamplight, the blue cars gleaming under rain droplets. Mechanics whisper: If these cars finish, they’ll rewrite history.

Hours 9–12 (Midnight – 3:00 AM) — Order and Precision

The night passes in rhythm. Wimille and Benoist swap driving duties seamlessly. The BMWs remain fast but cautious, their debut more about endurance than glory. A Riley retires with engine failure; another MG slides off at Tertre Rouge.

By 3 AM, the Bugatti #2 has built an eight-lap lead. The pits are quiet except for the rhythmic hum of its straight-eight engine echoing through the rain.

Hours 13–16 (3:00 – 6:00 AM) — Dawn and Discipline

As dawn rises over the Sarthe valley, the rain ceases. Mist clings to the trees. The blue Bugatti glides past the grandstands with regal calm. Behind, the remaining French cars have formed a protective phalanx — Delahaye, Talbot, and a surviving Bugatti — ensuring that home soil will claim the day.

For Wimille and Benoist, it’s no longer a battle but a test of restraint. Their lead is unassailable; the only enemy is complacency.

Hours 17–20 (6:00 – 9:00 AM) — The Morning March

The crowds return, waving tricolors and flags of Bugatti’s home province. The BMWs begin a late charge, chasing podiums. Their smoothness impresses; their reliability frightens competitors. It’s a warning for the future — but for now, France reigns supreme.

The Bugatti mechanics signal across the pit wall: “Tenez le rythme” — hold the rhythm. Wimille nods silently, his goggles fogged, his focus absolute.

Hours 21–23 (9:00 – 11:00 AM) — No Mistakes

The field is exhausted. Barely fifteen cars remain. The Bugatti #2 continues to lap without error, its tires worn but intact, its oil pressure steady. The only threat comes from within: fatigue. Benoist drives the penultimate stint, every corner exact, every downshift clean.

Hour 24 (11:00 AM – Noon) — A French Renaissance

As the clock strikes noon, the Bugatti 57G Tank crosses the line in triumph. The grandstands erupt. After years of British and Italian domination, France has reclaimed Le Mans. Wimille and Benoist embrace in front of the pit wall as blue flags wave in the wind.

Behind them, another Bugatti finishes second; the BMWs secure distant but celebrated top-five positions. For the first time in years, the tricolor flies highest.

The victory feels bigger than racing. It is France’s redemption — mechanical, emotional, and national — in the uncertain calm before the world darkens again.

Aftermath & Results

Winners: Jean-Pierre Wimille / Robert Benoist — Bugatti 57G Tank

Distance: 3 287.5 km

Average Speed: 136.99 km/h

Second: Pierre Veyron / Roger Labric — Bugatti 57G

Third: Henne / Falkenhausen — BMW 328

Fastest Lap: Jean-Pierre Wimille — 5′ 43″ (~145 km/h)

Notes:

The Bugatti 57G introduced full aerodynamic streamlining, setting a new endurance benchmark.

It marked France’s first overall Le Mans victory since 1926, and Bugatti’s only overall win.

The BMW 328’s performance foreshadowed German engineering dominance to come.

Benoist and Wimille, both heroes of pre-war racing, would later serve the French Resistance — their Le Mans triumph taking on poignant historical weight after the war.

Sources

Automobile Club de l’Ouest (ACO) — Official 1937 24 Heures du Mans Records

24h-lemans.com — “1937: The Return of Le Mans and the Bugatti Tanks”

Motorsport Magazine — July 1937 Issue Race Report

RacingSportsCars.com — 1937 Results Database

Goodwood Road & Racing — “Bugatti’s Triumph at Le Mans 1937”

Wikipedia — 1937 24 Hours of Le Mans

1938 — Triumph in Tragedy

Hour 0 (4:00 PM) — The Race Returns Under a Dark Sky

The mood is somber. Political tensions in Europe simmer beneath the surface, and thunderheads gather over the Sarthe Valley. Yet the crowd still comes — 43 cars on the grid, the air electric with engines and anxiety.

The French teams arrive in force: Delahaye, Talbot, and Bugatti stand ready to defend home soil after the Bugatti “Tank” triumph of 1937. Their rivals are equally formidable — BMW’s 328, Lagonda’s V12, and the first works-entered Alfa Romeo 2900B, a supercharged, 330-horsepower monster unlike anything seen before.

When the tricolor falls, the field explodes forward. The howl of engines mixes with thunder overhead. For all its grandeur, the 1938 Le Mans feels haunted from the first lap.

Hour 1 (5:00 PM) — The Red and the Blue

The Alfa Romeos take an immediate lead. Raymond Sommer’s scarlet car, partnered with Clemente Biondetti, storms down Mulsanne at over 220 km/h, leaving sprays of mist behind. The French Delahayes, nimble and lighter, cling to their slipstream.

By the end of the first hour, Sommer leads, chased by a trio of Delahayes — all running a careful pace, their drivers cautious in the worsening rain.

Hour 2 (6:00 PM) — Disaster at Maison Blanche

The storm intensifies, sheets of rain slashing across the track. Just before 6 PM, tragedy strikes: on the approach to Maison Blanche, the British driver R. T. O. Handley in a Riley loses control on standing water. His car skids sideways into the path of the Frenchman Pat Fairfield. The impact sends both machines tumbling into the embankment.

The wreckage bursts into flames. Marshals rush forward, but the inferno is too fierce. Both drivers perish within minutes. The race continues, but the grandstands fall silent. The 1938 race will forever carry their names in mourning.

Hours 3–4 (7:00 – 8:00 PM) — Rain and Resolve

Even as grief spreads through the pits, the race pushes on. Sommer drives with fury, pulling clear of the French pack. The Delahaye 135CS of Eugène Chaboud and Jean Trémoulet counters with consistent laps, staying within reach.