Le Mans 1949- 1969

Post-War Sports Cars

1949 — Rebirth After the War

Hour 0 (4:00 PM) — The Race Returns

Ten years have passed since the last Le Mans. The circuit bears scars of war — cracked tarmac, rebuilt grandstands, bullet-pocked guardrails. France itself is rebuilding, but the 24 Hours returns as a symbol of renewal.

Fifty-six cars line the grid, an extraordinary act of defiance and hope. New faces and machines stand where legends once did: Ferrari, Jaguar, Talbot-Lago, Aston Martin, Simca, and Delahaye. Many are driven by veterans who had traded helmets for uniforms, now back to reclaim their passion.

The tricolor falls. Engines roar — a sound Europe hasn’t heard in a decade. The 1949 24 Hours of Le Mans begins.

Hour 1 (5:00 PM) — Red Revival

Immediately, the Ferraris capture attention. Two factory-supported 166MM Barchettas — small, nimble, and achingly beautiful — surge forward. Their twelve-cylinder song echoes off the rebuilt pit wall. In car #22, a dark-haired Italian gentleman and an English aristocrat share the cockpit: Luigi Chinetti and Lord Selsdon.

The Talbot-Lagos, elegant but heavy, chase them closely. The Simcas and Delahayes run for national pride. A handful of British privateers — Jaguars and Aston Martins — represent a rising island of speed.

The first hour ends with Chinetti’s Ferrari among the leaders, its tiny V12 defying its size with speed and melody.

Hours 2–3 (6:00–7:00 PM) — France Fights Back

The French Talbots of Rosier and Louveau fight hard, their straight-sixes punching down Mulsanne with thunderous rhythm. The crowds — many attending in wartime uniforms — cheer their countrymen madly.

Yet the Ferraris run differently. Where the Talbots bellow, the 166MM hums — revving high, smooth, and unbothered. Its light frame skips over the cracks in the circuit that still whisper of war.

As dusk falls, a sense of history returns. Le Mans breathes again.

Hours 4–8 (8:00 PM – Midnight) — Night of the Phoenix

Darkness descends, and the floodlights reflect on wet pavement — a brief rain shower sweeps through the valley. The French cars lose time in pit repairs; the Ferraris glide through. Chinetti, now in the car for hours on end, refuses to rest. His co-driver, Lord Selsdon, offers to take over, but Chinetti insists:

“The car feels alive in my hands. I must finish what we started.”

Through the night, the red Barchetta becomes a glowing ember carving through mist.

Hours 9–12 (Midnight – 3:00 AM) — The Endurance of One Man

While others swap drivers every few hours, Chinetti simply continues. Hour after hour, he stays behind the wheel — his eyes hollow but focused, his rhythm perfect. He has now driven nearly two-thirds of the race alone.

The Talbots suffer — one retires with gearbox failure, another with a broken crankshaft. The Aston Martins lose ground. The French crowd, grudgingly admiring, begins to cheer the Italian who refuses to stop.

By 3 AM, Ferrari leads.

Hours 13–16 (3:00 – 6:00 AM) — The Dawn of Ferrari

The first light of morning finds Chinetti still driving. His gloves are soaked with sweat; his face is pale. He finally gives the car to Selsdon for a short stint — less than 90 minutes — before taking the wheel again.

By sunrise, the Ferrari 166MM holds a narrow but firm lead over Louveau’s Talbot-Lago. The little red car, barely 2 liters in displacement, has outlasted giants.

Hours 17–20 (6:00 – 9:00 AM) — The Ferrari March

Morning clears, the circuit glistens. The Ferrari’s rhythm remains flawless — refuel, clean the screen, check the oil, go again. The Talbot presses but begins to overheat. The Aston Martins drop away, one by one.

Chinetti’s relentless drive begins to feel mythical. Spectators realize they are watching not just a race, but a resurrection — of Ferrari, of Le Mans, and of spirit itself.

Hours 21–23 (9:00 – 11:00 AM) — The Human Machine

By now, Chinetti has driven nearly 22 of the 24 hours. He can barely stand during pit stops, collapsing briefly before climbing back in. Reporters watch in disbelief as he wipes his brow, starts the engine, and roars back into the dawn.

The Ferrari’s engine sings unchanged. The crowd roars every lap.

Hour 24 (11:00 AM – Noon) — The Rebirth of Le Mans

At noon on June 19th, the red Ferrari 166MM Barchetta crosses the finish line. Luigi Chinetti raises a trembling hand. Exhausted, soaked, and weeping, he has done the impossible — driving all but 72 minutes of the race himself.

Behind him, the Talbot-Lago of Louveau and Levegh finishes second, proud but beaten. France applauds; Italy celebrates.

Ferrari, founded only two years earlier, is now immortal.

Le Mans lives again.

Aftermath & Results

Winners: Luigi Chinetti / Lord Selsdon — Ferrari 166MM Barchetta

Distance: 3,177.34 km

Average Speed: 132.95 km/h

Second: Pierre Louveau / René Levegh — Talbot-Lago T26GS

Third: Henri Louveau / Jean de Pourtales — Delahaye 175S

Fastest Lap: Luigi Chinetti — 5′41″ (~148 km/h)

Notes:

This was the first Le Mans held after World War II, symbolizing Europe’s rebirth.

Ferrari’s first Le Mans victory, achieved just two years after its founding.

Luigi Chinetti drove roughly 23 of 24 hours, one of the most astonishing solo endurance feats in racing history.

The race marked the beginning of Ferrari’s legacy at Le Mans — one that would stretch across decades.

The event’s success proved Le Mans could survive war, politics, and loss — and still inspire the world.

Sources

Automobile Club de l’Ouest (ACO) — Official 1949 24 Heures du Mans Records

24h-lemans.com — “1949: The Return of the 24 Hours”

Motorsport Magazine — July 1949 Race Report

RacingSportsCars.com — 1949 Results Database

Goodwood Road & Racing — “Chinetti and the Race that Rebuilt Le Mans”

Wikipedia — 1949 24 Hours of Le Mans

1950 — The Return of the Machines

Hour 0 (4:00 PM) — The Modern Age Begins

Le Mans awakens to a new decade. The scars of war are fading, replaced by optimism and machinery more sophisticated than ever before.

The grandstands glimmer with fresh paint; the field brims with legends in the making: Ferrari, Aston Martin, Jaguar, Talbot-Lago, Allard, and Delahaye.

Fifty-six cars line the grid. At the front, the bright red Ferrari 166MMs of Luigi Chinetti and Lord Selsdon — last year’s heroes — idle beside the powerful Talbot-Lago T26s, France’s pride. Among them, a newcomer from Coventry stands quietly: the sleek green Jaguar XK120, its aluminum body reflecting the clouds.

The tricolor falls. Engines scream. Le Mans 1950 is underway — and so is the modern era of endurance racing.

Hour 1 (5:00 PM) — The Thunder of Talbot

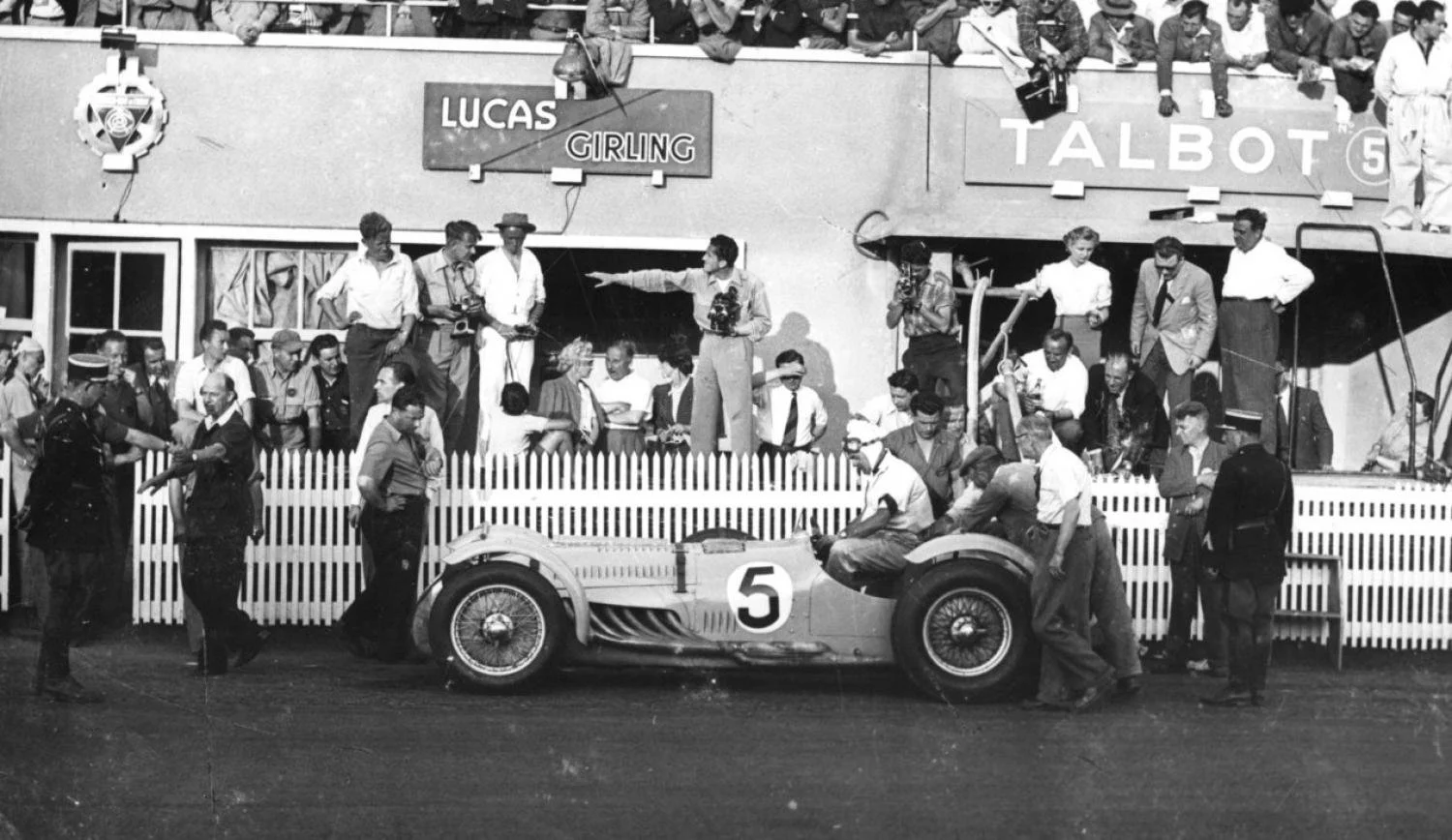

The Talbot-Lagos charge to the front. Their massive 4.5-litre straight-sixes bellow down the Mulsanne, overwhelming the smaller Ferraris in sheer power. Pierre Meyrat and Guy Mairesse lead, followed closely by Louis Rosier’s #5 Talbot.

The Ferraris, nimble but less robust, bide their time. The Jaguars — fast but untested — stay mid-pack, pacing themselves.

By the end of the first hour, the Talbots roar at the front, but the green Jaguars begin to impress with their smoothness.

Hours 2–3 (6:00–7:00 PM) — The Race of Contrasts

The pattern becomes clear: French muscle versus Italian finesse versus British poise. The Talbots storm the straights but brake poorly. The Ferraris corner beautifully but strain on the long Mulsanne. The Jaguars, their twin-cam engines new to endurance, run quietly — perhaps too quietly to be trusted.

Crowds line every hill and farmhouse roof, watching this new battle of philosophies unfold.

Hours 4–8 (8:00 PM – Midnight) — Nightfall and Nerves

As the first postwar night settles, the race transforms. Headlights flicker across the damp circuit. The Talbots begin to falter — brake fade, overheating, and gear selection trouble. One retires near Arnage, another limps into the pits with oil loss.

The Ferraris hold steady, but their smaller engines can’t sustain top speed for long. Aston Martin runs beautifully but lacks outright pace.

And through it all, the Jaguars keep going. Peter Whitehead and Peter Walker’s #15 XK120 creeps upward, lap by lap. They are quiet, efficient, and relentless — the first signs of British engineering precision that will soon redefine Le Mans.

Hours 9–12 (Midnight – 3:00 AM) — The Night Trials

The field shrinks to forty. The Talbots pit for extended repairs. The Ferraris, led by Chinetti and Selsdon again, remain in contention. At 2 AM, Rosier’s Talbot retakes the lead — driving alone for long stretches, a feat soon to become legend.

Meanwhile, the Jaguars prove astonishingly reliable, though slower. None have yet retired. The British cars run as if made of quiet confidence.

Hours 13–16 (3:00 – 6:00 AM) — Dawn at Le Mans

Dawn breaks over a misty Sarthe. The Talbot-Lago #5 still leads, Rosier pushing beyond reason. His co-driver, his son Jean-Louis, rests in the pits — his father refuses to hand over the wheel.

Behind, the Ferrari of Chinetti begins to fade with clutch issues. The Jaguars hold fifth and seventh, strong for a debut.

The circuit glows under early sunlight, the smoke of oil fires curling over the horizon.

Hours 17–20 (6:00 – 9:00 AM) — The French Ironman

Rosier continues to drive — lap after lap, hour after hour. By now, he has been in the car for nearly twenty consecutive hours, a feat of will bordering on madness. His Talbot’s brakes are almost gone; the gearbox whines. Yet he presses on, maintaining a modest gap to the Ferraris and Delahayes.

Chinetti, exhausted from last year’s heroics, pushes his wounded Ferrari as high as third before mechanical failure ends his defense.

The Jaguars keep rolling, their debut now a quiet triumph of endurance.

Hours 21–23 (9:00 – 11:00 AM) — A Battle of Attrition

The final hours are brutal. The Talbot’s rear axle creaks ominously, its tires nearly bald. Rosier ignores it all. He is possessed, driving smoother than ever, his rhythm unbreakable.

Behind him, the Delahaye of Gérard and Galland stalks the lead, only for its clutch to fail within the final hour. The Ferrari is gone. The Jaguars are distant but running perfectly.

The crowd begins to chant: “Rosier! Rosier!”

Hour 24 (11:00 AM – Noon) — One Man’s Le Mans

At noon, after 24 grueling hours, Louis Rosier crosses the finish line — utterly alone. He has driven 23 of the 24 hours himself, ceding just 45 minutes to his son.

France erupts. The blue Talbot-Lago T26C has conquered the race through endurance, courage, and stubborn human will. It is a victory of man over machine — and the last great triumph of the pre-Ferrari era.

Behind him, the Delahaye hobbles home in second. The Jaguars finish sixth and twelfth — astonishing reliability for their debut. Ferrari, meanwhile, vanishes into the mist of mechanical defeat.

Aftermath & Results

Winners: Louis Rosier / Jean-Louis Rosier — Talbot-Lago T26GS

Distance: 3,657.8 km

Average Speed: 152.27 km/h

Second: Jean-Pierre Wimille / André Morel — Delahaye 175S

Third: François Meyrat / Guy Mairesse — Talbot-Lago T26GS

Sixth: Peter Whitehead / Peter Walker — Jaguar XK120

Fastest Lap: Louis Rosier — 4′44″ (~170 km/h)

Notes:

This was France’s third consecutive Le Mans victory, and Talbot’s finest hour.

Louis Rosier drove nearly the entire race solo — a feat rivaling Chinetti’s endurance from 1949.

The debut of the Jaguar XK120 heralded a new era of British precision and speed that would dominate the 1950s.

Ferrari’s mechanical struggles would soon give way to innovation — by 1953, the marque would return to reclaim glory.

1950 marked the true transition from prewar grit to modern motorsport professionalism.

Sources

Automobile Club de l’Ouest (ACO) — Official 1950 24 Heures du Mans Records

24h-lemans.com — “1950: Rosier’s One-Man Victory”

Motorsport Magazine — July 1950 Race Report

RacingSportsCars.com — 1950 Results Database

Goodwood Road & Racing — “Louis Rosier: The Man Who Drove Alone”

Wikipedia — 1950 24 Hours of Le Mans

1951 — Jaguar’s First Roar

Hour 0 (4:00 PM) — The New Battle Lines

The heat of June hangs over the Sarthe Valley as fifty entries roar to life.

On the front row: the returning Ferrari 340 America — a bellowing V12 brute — alongside the elegant, understated Jaguar C-Type, a brand-new aluminum racer built purely for endurance.

Ferrari fields three works cars. Jaguar brings two factory C-Types, both with the new XK engine and revolutionary wind-tunnel-tested bodywork. France counters with Talbot-Lagos and Delahayes. Aston Martin, Allard, and Nash-Healey complete a field representing every major racing nation.

When the tricolor falls, the roar is unlike anything heard since before the war. Le Mans 1951 begins — a clash between art, muscle, and aerodynamics.

Hour 1 (5:00 PM) — The C-Types Strike

Right from the start, the sleek Jaguars surge forward. Peter Walker and Peter Whitehead’s #20 C-Type runs flawlessly, its disc brakes and streamlined shell giving it stability others can only envy. Ferrari counters immediately — Luigi Villoresi and Piero Taruffi in the #22 340 America blasting down Mulsanne with ferocious top speed.

Behind them, the Talbots keep a steady rhythm; the Aston Martins lose ground early. The first hour ends with the Ferraris leading on raw pace — but the Jaguars gaining with efficiency and elegance.

Hours 2–3 (6:00–7:00 PM) — Heat and Heartbeats

The afternoon grows hotter. Radiators boil; brakes fade. The Ferraris begin to suffer from fuel vapor-lock; one pits for emergency repairs. The Jaguars, cooler and lighter, maintain their tempo.

Whitehead takes the lead at dusk. The British cars run smooth, efficient — a new kind of dominance built on precision rather than bravado.

Hours 4–8 (8:00 PM – Midnight) — Nightfall and the Sound of Aluminum

Under starlight, the C-Types are mesmerizing. Their silver-green bodies flash across the dark straights like living metal. Walker and Whitehead share near-identical lap times, swapping effortlessly at each refuel.

Ferrari fights back valiantly, Taruffi wringing every ounce from the 4.1-liter V12. The duel feels like a generational shift — the British era beginning to eclipse the Italian.

By midnight, only the two lead cars — Jaguar #20 and Ferrari #22 — remain within a lap of each other.

Hours 9–12 (Midnight – 3:00 AM) — The Endurance Test

The field thins. Over twenty cars retire with mechanical issues or accidents. The Talbots and Allards, brave but overworked, fall behind.

The Jaguar runs without a hiccup. Ferrari’s pit crew works feverishly to fix a misfire, losing precious minutes. At 2 AM, the C-Type reclaims the lead — not through sheer speed, but through engineering purity.

Hours 13–16 (3:00 – 6:00 AM) — Dawn of a New Order

The rising sun gleams off aluminum curves. The crowd, bleary-eyed but enthralled, senses history unfolding. Jaguar’s debut prototype — designed by William Lyons and Malcolm Sayer — is proving unstoppable.

Ferrari’s V12s sound magnificent but weary. One engine explodes spectacularly down Mulsanne, scattering debris into the grass. Another limps into retirement with gearbox failure.

By sunrise, only one Ferrari remains, hopelessly out of reach.

Hours 17–20 (6:00 – 9:00 AM) — The Calm Before Glory

With morning light comes control. The Jaguars back off slightly, nursing engines and brakes. The C-Type’s aluminum body, built for low drag, allows the car to run 20 km/h faster than the heavier Ferraris on less fuel.

The Talbots and Allards pick up the pieces for the lower positions. Aston Martin is long gone.

Whitehead and Walker maintain a flawless rhythm — their lap chart a portrait of precision.

Hours 21–23 (9:00 – 11:00 AM) — Unstoppable Green

By late morning, the C-Type’s lead is enormous. Ferrari’s last challenger fades with carburetor issues. The crowd begins to celebrate early; British flags wave among the tricolors.

The Jaguars, their aluminum bodies now streaked with oil and dust, hum like aircraft on approach. The pit wall signals: “No risks. Bring her home.”

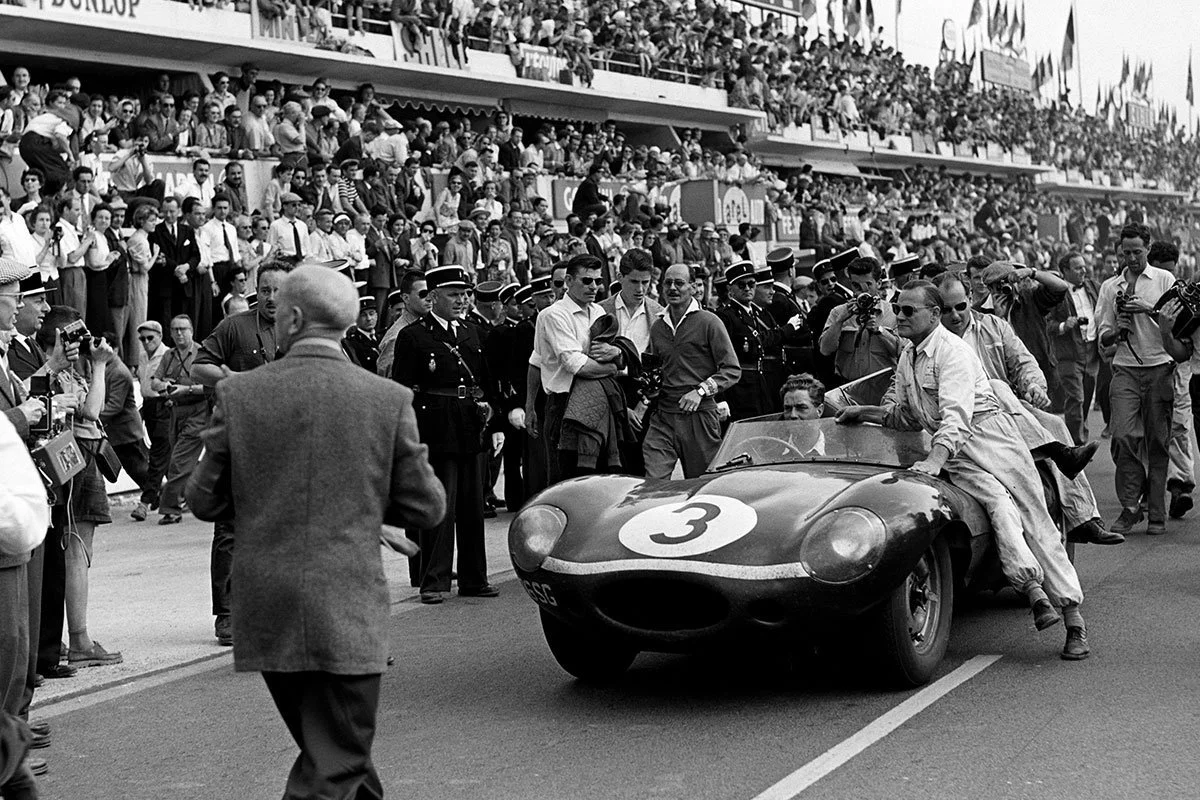

Hour 24 (11:00 AM – Noon) — Britain Triumphant

At high noon, the #20 Jaguar C-Type crosses the finish line first — serene, silver, perfect. Peter Walker lifts his goggles; Peter Whitehead climbs onto the pit wall, waving to the roaring crowd.

It is Jaguar’s first victory at Le Mans — achieved on their very first attempt.

Behind them, the Talbot-Lago of Meyrat and Mairesse finishes second, battered but proud. Ferrari trails far behind, outclassed by the new aerodynamic age.

The modern Le Mans era has arrived — and it hums to the sound of a twin-cam British straight-six.

Aftermath & Results

Winners: Peter Walker / Peter Whitehead — Jaguar C-Type

Distance: 3,433.35 km

Average Speed: 143.45 km/h

Second: Pierre Meyrat / Guy Mairesse — Talbot-Lago T26GS

Third: Louis Rosier / Jean-Louis Rosier — Talbot-Lago T26GS

Fastest Lap: Luigi Villoresi (Ferrari 340 America) — 4′46″ (~172 km/h)

Notes:

Jaguar’s first Le Mans victory, achieved on debut, marked Britain’s return to racing greatness.

The C-Type introduced true aerodynamic efficiency to endurance racing and paved the way for the dominance of lightweight design.

Ferrari’s brute-force V12s were fast but fragile; Enzo Ferrari would return in 1953 with vengeance.

Jaguar’s victory turned Le Mans from a French tradition into a global stage — the duel between Coventry and Maranello had begun.

Sources

Automobile Club de l’Ouest (ACO) — Official 1951 24 Heures du Mans Records

24h-lemans.com — “1951: Jaguar’s First Victory”

Motorsport Magazine — July 1951 Issue Race Report

RacingSportsCars.com — 1951 Results Database

Goodwood Road & Racing — “How the C-Type Conquered Le Mans”

Wikipedia — 1951 24 Hours of Le Mans

1952 — Return of the Silver Arrows

Hour 0 (4:00 PM) — A Silver Silence Broken

Fourteen June 1952. Ten years after the guns fell silent in Europe, the Mulsanne straight again trembles with speed. The world has changed, but the spirit of Le Mans endures. Fifty-eight cars line the grid beneath heavy clouds: Ferraris from Maranello, Aston Martins and Jaguars from Britain, Talbot-Lagos for France — and, at the center of attention, three long-nosed, silver-painted machines bearing the star of Mercedes-Benz.

After twenty-two years away, Stuttgart has returned. Their weapon is the W194, an aerodynamic coupé derived from the 300 SL, its magnesium-alloy body shaped by wind-tunnel testing, its straight-six engine canted steeply to lower the bonnet. Inside, drivers Hermann Lang, Fritz Riess, Theo Helfrich, and Helmut Niedermayr sit within doors hinged into the roof — the first “Gullwings.”

At 4 PM, the tricolor drops. The silence of exile ends with a metallic scream.

Hour 1 (5:00 PM) — Silver vs Scarlet

The first laps belong to Ferrari. Luigi Chinetti and André Simon’s 340 America charges down Mulsanne, its V12 bellowing. But the Mercedes, serene and balanced, stalk from behind. Lang’s car glides past the pits at 250 km/h — slower on paper, yet impossibly efficient through the curves.

Behind, Jaguar’s C-Types suffer from fuel-boiling in the unexpected heat, while Talbot-Lagos — heavy but durable — plod steadily.

Hours 2–3 (6:00–7:00 PM) — The Method of Stuttgart

As evening deepens, the rhythm emerges: Mercedes’ engineers have planned this like an endurance experiment, not a race. Every 32 laps, the cars pit with surgical precision — refuel, change tires, wipe windscreens, no wasted motion.

Ferrari, by contrast, relies on bursts of aggression; the Jaguars are already in distress.

Hours 4–8 (8:00 PM – Midnight) — Night of the Silver Wings

Darkness falls and with it comes rain. Many drivers lose their nerve, but the Mercedes coupés thrive. Their enclosed bodies keep the cockpits dry and the aerodynamics stable. Lang, a pre-war ace now reborn, drives flawlessly through the downpour, his headlight beams cutting clean lines through mist.

By midnight, both leading Ferraris have succumbed — one to clutch failure, the other to a cracked cylinder head. The W194s run one-two, chased only by the lonely Talbot of Pierre Levegh, a privateer determined to drive alone for all 24 hours.

Hours 9–12 (Midnight – 3:00 AM) — Attrition and Resolve

The rain worsens. Cars aquaplane off the road at Arnage and Maison Blanche. Jaguars withdraw, their radiators boiled dry. Yet the silver machines remain unruffled. Riess and Lang exchange quiet words at each pit stop; the only instruction from team manager Neubauer is: “Nur konstant — only constant.”

Levegh, astonishingly, is still third — his Talbot held together by sheer will.

Hours 13–16 (3:00 – 6:00 AM) — Dawn Over the Sarthe

The storm breaks at dawn. Mist clings to the trees as the W194s flash past the pits, their aluminum bodies shimmering. Ferrari is gone, Jaguar broken, Aston Martin limping. Mercedes now races only itself — the lead unchallenged.

Lang drives with a veteran’s patience; his hands never leave the wheel except to salute the mechanics on each pass.

Hours 17–20 (6:00 – 9:00 AM) — Levegh’s Defiance

The Talbot continues, heroically, Levegh refusing to rest. His lap times waver but his spirit does not. For every elegant glide of the Mercedes, the Frenchman offers a hammer-blow of endurance. The crowd begins to split its allegiance — half cheering the silver perfection, half the solitary blue Talbot and its indomitable driver.

Hours 21–23 (9:00 – 11:00 AM) — Control and Caution

Neubauer signals his cars to hold pace: “Keine Risiken — no risks.” The Mercedes pair circulate in harmony, averaging 155 km/h, engines unstressed. Levegh’s Talbot, now a miracle of persistence, is still third — but its oil pressure flickers ominously.

Hour 24 (11:00 AM – Noon) — Victory in Silver

As the final hour unfolds, the crowd rises in respect. At precisely noon, Hermann Lang and Fritz Riess cross the line to claim Mercedes-Benz’s first Le Mans victory — a one-two finish, the W194s faultless to the end.

Moments later, Levegh’s Talbot coughs, slows, and dies within sight of the pits. The con-rod has snapped. He steps out, tears in his eyes, bowing to the crowd that now cheers him louder than the winners.

Aftermath & Results

Winners: Hermann Lang / Fritz Riess — Mercedes-Benz W194 300 SL

Second: Theo Helfrich / Helmut Niedermayr — Mercedes-Benz W194 300 SL

Third: Leslie Johnson / Tommy Wisdom — Nash-Healey Le Mans Coupe

Distance: 3,733 km @ 155.6 km/h

Significance:

Mercedes-Benz’s first overall win at Le Mans and the only race outing for the W194, precursor to the 300 SL road car.

The return of Hermann Lang, who had last raced for Mercedes in 1939.

Pierre Levegh’s solo run became one of endurance racing’s immortal legends.

The enclosed-body coupé set a precedent — aerodynamics and reliability had permanently eclipsed brute horsepower.

Sources

Automobile Club de l’Ouest (ACO) — 1952 24 Heures du Mans official results and race notes

Mercedes-Benz Classic Archives — “The 1952 Le Mans Victory of the 300 SL” (Stuttgart, 2012 edition)

Motorsport Magazine, July 1952 contemporary report; July 2022 retrospective “Only Mercedes Had Luck Left in the Tank”

Supercar Nostalgia — “Mercedes-Benz W194 Chassis 00007/52” technical dossier

Automobilist Stories — “Wings of Change: The 300 SL at Le Mans”

1953 — The Aerodynamic Age

Hour 0 (4:00 PM) — The Shape of the Future

A hot June sun glints off a new kind of Le Mans grid. Gone are the upright coupés and boxy saloons; in their place are low, flowing machines shaped by air and logic.

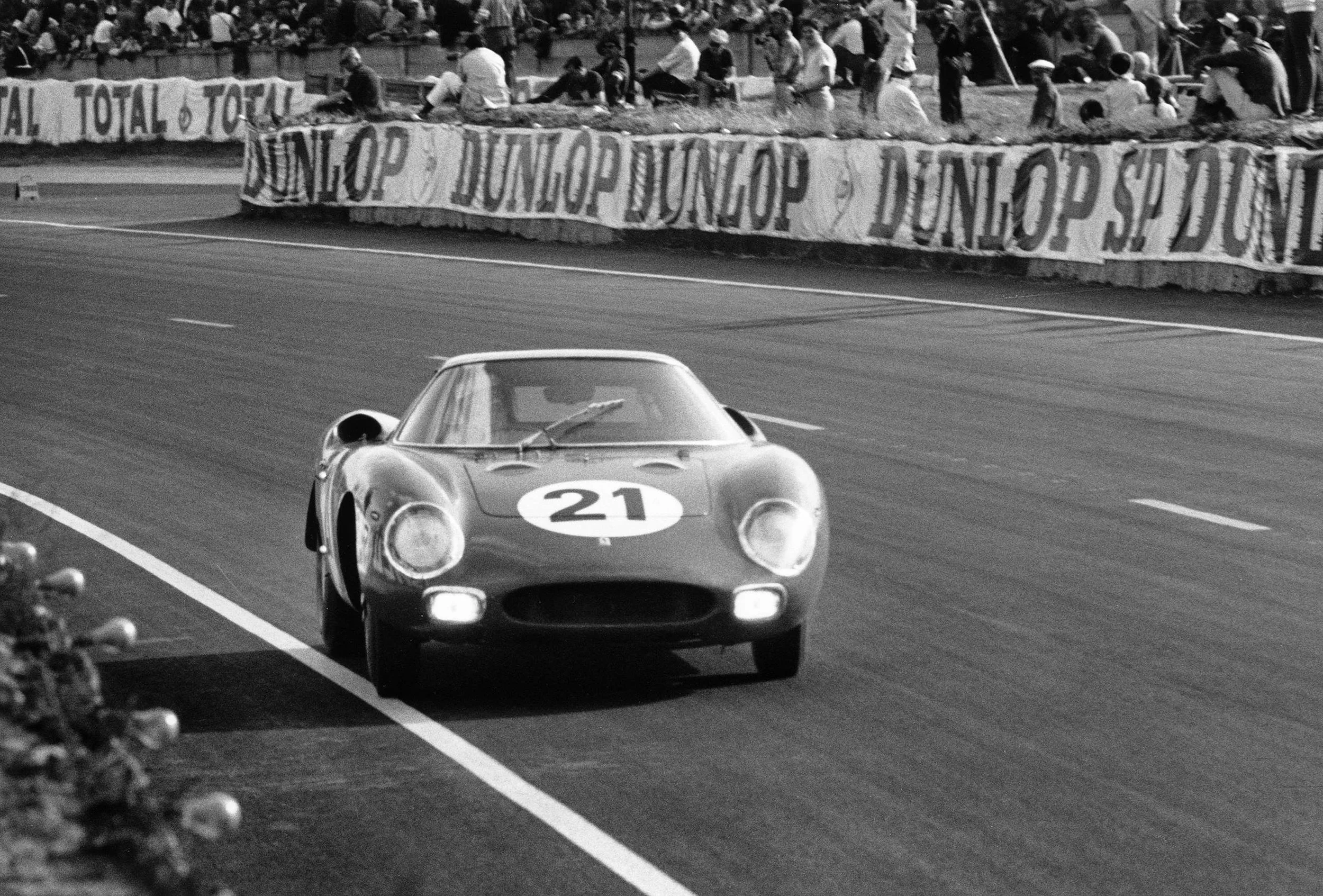

At the front stand Ferrari’s 340 MMs — V12 monsters of raw power. Opposite them, Jaguar’s latest creation: the D-Type, unveiled just weeks before the race. Its shape is revolutionary — a tapering body with a vertical stabilizing fin behind the driver, and most radically, Dunlop disc brakes, the first ever fitted to a Le Mans car.

Ferrari arrives with might: Ascari, Villoresi, and Farina among its ranks. Jaguar fields three works D-Types driven by Tony Rolt, Duncan Hamilton, Peter Walker, and Stirling Moss. Aston Martin’s DB3S looks elegant but fragile. Cunningham’s American team returns with brawny white roadsters.

When the tricolor falls, history begins again.

Hour 1 (5:00 PM) — A Green Flash at Mulsanne

The Ferraris thunder away first, their twelve cylinders shattering the afternoon quiet. But within minutes, the Jaguars show their hand: smoother, cooler, and aerodynamically superior. The D-Type of Rolt and Hamilton slingshots down Mulsanne at 155 mph — five faster than the Ferraris, yet burning less fuel.

By the end of the hour, the British cars are already inside the top five. The French crowd, partial to local Talbots, senses a new order forming.

Hours 2–3 (6:00–7:00 PM) — Red Heat

The Ferraris hold nothing back. Ascari sets a searing pace, his car darting through traffic like a knife. The Jaguars match him lap for lap, their disc brakes allowing later entries and cleaner exits from Arnage and Maison Blanche. The D-Type’s stability is uncanny — it slices straight even through gusting crosswinds.

Behind them, the Aston Martins already fall behind with axle issues. The Cunninghams rumble on defiantly, brute force against British finesse.

Hours 4–8 (8:00 PM – Midnight) — Nightfall and Precision

As dusk paints the sky violet, the Jaguars and Ferraris remain locked in a duel of efficiency versus ferocity. Hamilton drives flawlessly, matching Ascari’s times yet never over-revving. Pit stops become choreography — the British crews refueling with clockwork discipline, while Ferrari’s mechanics wrestle with boiling fuel tanks.

At 10 PM, Ascari’s Ferrari 375 MM suffers brake failure at Arnage and spins into the barrier. He is unharmed, but the challenge of Maranello begins to falter. Only Luigi Villoresi remains in contention.

By midnight, the D-Type of Rolt/Hamilton leads by a narrow margin over Villoresi’s Ferrari and the American Cunningham.

Hours 9–12 (Midnight – 3:00 AM) — Through the Darkness

The night is clear and cold. The Jaguars thrive. Their disc brakes stay consistent while others fade. Moss’s sister car retires after overheating, but the lead machine remains flawless.

Ferrari fights on, its V12s shrieking down Mulsanne, but every stop grows longer — the drums glowing red. The Cunningham C-4R of Fitch and Walters climbs steadily to third, a transatlantic marvel of endurance.

Hours 13–16 (3:00 – 6:00 AM) — The Dawn Duel

The first light reveals two survivors of the lead battle: Jaguar’s #18 D-Type and Ferrari’s #12 340 MM. For hour after hour, they trade fastest laps — Hamilton wringing every ounce of speed from the car, Villoresi refusing to yield.

At 5 AM, the decisive moment comes: the Ferrari loses its clutch at Tertre Rouge. It limps to the pits, where mechanics work frantically but cannot revive it. The D-Type, suddenly alone, is ordered to ease its pace — but the drivers refuse.

Hours 17–20 (6:00 – 9:00 AM) — The March of Perfection

By mid-morning, Jaguar leads comfortably. The C-Type of Moss/Walker runs several laps down but steady. The only remaining Ferrari is crippled. The D-Type’s pit wall signals “EASY,” but Hamilton shakes his head — the car is effortless, the brakes cool, the revs clean.

Crowds cheer as the green machine flashes past every two minutes — the first car in Le Mans history to make progress look serene.

Hours 21–23 (9:00 – 11:00 AM) — Rivals in Ruins

Ferrari’s final car succumbs to transmission failure. Aston Martin retires both entries. The Cunninghams continue bravely but can’t touch the Jaguars’ economy.

Every pit stop for Rolt and Hamilton is flawless — no wasted seconds, no drama. For the first time, Le Mans looks more like a laboratory than a battlefield.

Hour 24 (11:00 AM – Noon) — Disc Brakes and Destiny

At noon, the Jaguar D-Type #18 glides across the finish line, two laps ahead of the field. Rolt and Hamilton raise their arms as one; William Lyons watches from the pit wall, beaming.

It’s Britain’s second win in three years, but its significance runs deeper: Jaguar has introduced the technology — disc brakes, wind-tunnel aerodynamics, lightweight monocoques — that will define endurance racing.

Behind them, the Cunninghams finish gallantly in third. Ferrari’s pit is silent.

The world’s greatest race has entered its modern age.

Aftermath & Results

Winners: Tony Rolt / Duncan Hamilton — Jaguar C-Type

Distance: 3,452 km @ 144.3 km/h

Second: Luigi Villoresi / Paolo Maran — Ferrari 340 MM (DNF but classified)

Third: Phil Walters / John Fitch — Cunningham C-4R

Fastest Lap: Stirling Moss (Jaguar C-Type) — 4′24″ (~183 km/h)

Key Significance:

Jaguar’s second overall victory, introducing disc brakes and full aerodynamic optimization to endurance racing.

The C-Type’s efficiency forced every rival to rethink cooling, braking, and body design.

Ferrari’s pace proved their power but underscored fragility — their first real defeat in postwar endurance.

The 1953 event became the blueprint for modern Le Mans: precision, data, and innovation outlasting brute force.

Sources

Automobile Club de l’Ouest (ACO) — Official 1953 24 Heures du Mans Records & Lap Charts

Jaguar Heritage Trust Archives — “The 1953 Le Mans Victory of the C-Type”

Motorsport Magazine, July 1953 Issue — “Jaguar’s Disc-Braked Masterpiece”

The Autocar, June 26 1953 Race Report — “The C-Type at Speed”

Goodwood Road & Racing — “How Jaguar Invented the Modern Le Mans Car”

1954 — Silver Storm, Scarlet Fire

Hour 0 (4:00 PM) — The Giants Return

The Le Mans grandstands overflow under a sky streaked with thin summer clouds. The roar of anticipation is as loud as the cars themselves. For the first time since their 1952 triumph, Mercedes-Benz is back — and this time, not with a curvaceous coupé, but with a raw, open, predatory machine: the 300SLR W196/54.

Their drivers are heroes of the new Grand Prix age: Juan Manuel Fangio and Karl Kling, paired in one car; Hans Herrmann and Hermann Lang in another.

Facing them are the defending British champions — Jaguar, now fielding the striking D-Type in its first Le Mans appearance, driven by Stirling Moss, Peter Walker, Tony Rolt, and Duncan Hamilton. Its long, finned tail gleams dark green in the afternoon sun.

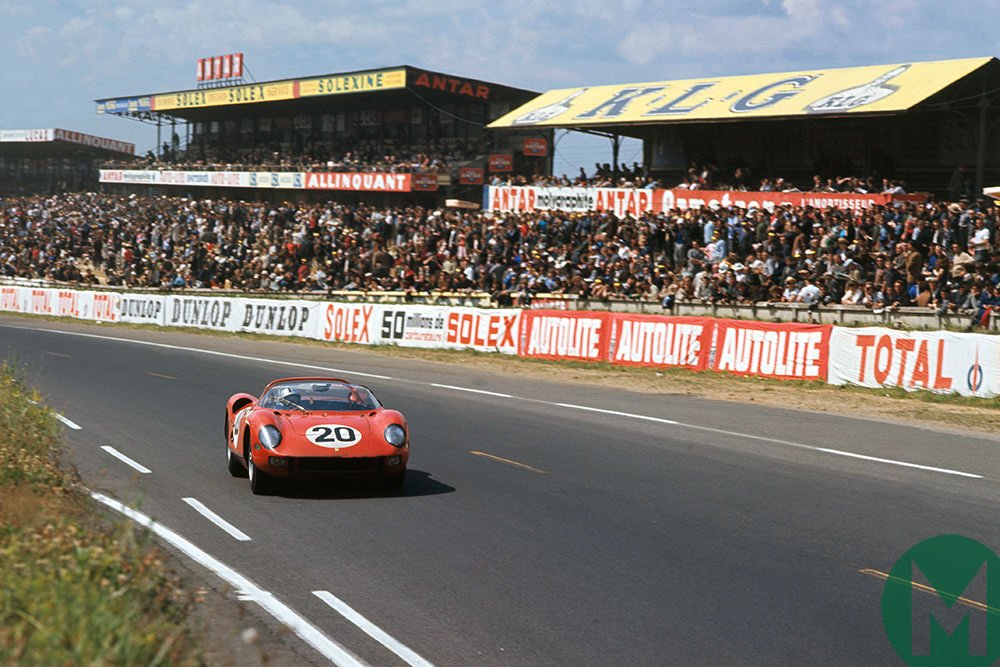

Across the pits, Ferrari brings the thunder: a squadron of 375 Plus machines, their 4.9-litre V12s producing nearly 340 horsepower — the most powerful fielded at Le Mans to date. Drivers include José Froilán González, Maurice Trintignant, Mike Hawthorn, and Umberto Maglioli.

The tricolor falls. Forty-six engines erupt.

Le Mans 1954 begins — and the titans go to war.

Hour 1 (5:00 PM) — Red Power

The Ferraris blast away first, their sheer horsepower overwhelming all else. González’s #4 375 Plus takes the early lead, pursued by the sleek silver Mercedes and the aerodynamic green D-Types.

The Ferraris thunder down Mulsanne at over 170 mph — faster than anything seen before. The Jaguars, while slower in top speed, slice through the Porsche curves with impossible smoothness, their disc brakes glowing but unfading.

Hours 2–3 (6:00–7:00 PM) — Duel of the Decade

By the third hour, the race has settled into a furious pattern. The leading Ferrari and Mercedes are separated by seconds, trading fastest laps every time they pass the pits. Fangio’s white-helmeted figure looks serene at 250 km/h, the Mercedes’ inline-six engine singing a mechanical aria of efficiency.

The Jaguars, for all their grace, are struggling with fuel feed issues and high cockpit temperatures. Moss complains of fumes in the cabin; Hamilton’s D-Type develops a misfire. The Ferraris, meanwhile, tear through the opening hours like gladiators with no thought of dawn.

Hours 4–8 (8:00 PM – Midnight) — Heat, Haste, and Havoc

As night falls, the weather turns. Warm rain sweeps across the Sarthe, turning the pit straight into a mirror. Fangio wrestles the Mercedes through Arnage, while González keeps his Ferrari howling in defiance. The crowd cheers both — it feels less like a race and more like a duel for eternity.

At 9 PM, the Mercedes #20 of Herrmann and Lang skids at Maison Blanche and crashes heavily. Both drivers escape, but the car is wrecked. Mercedes’ hopes now rest entirely on Fangio and Kling.

Jaguar’s Moss continues valiantly but loses oil pressure; one D-Type retires before midnight. The other soldiers on, running third.

By midnight, Ferrari leads. The red cars of González/Trintignant and Maglioli/Hawthorn sit one-two, with the lone silver Mercedes a constant shadow behind.

Hours 9–12 (Midnight – 3:00 AM) — Rain and Ruthlessness

The rain grows heavier. Pit stops become frantic ballets of rags, funnels, and shouted French. Fangio pits just past 1 AM, exhausted and shaking — the windscreen wipers have failed, visibility near zero. Kling takes over, determined to keep pressure on Ferrari.

The Jaguars, too, struggle. Hamilton’s car loses its tail light and must pit for repairs. The D-Type’s advanced body is stunning in the dry but treacherous in spray; every aquaplane feels like fate teasing.

The Ferraris remain unrelenting. González drives with the force of a man possessed. “This is not driving,” one journalist writes in Motorsport, “this is war in motion.”

Hours 13–16 (3:00 – 6:00 AM) — The Night Breaks

At dawn, the rain stops. Steam rises from the circuit, and the Ferraris stretch their lead. Fangio’s Mercedes develops electrical issues; the silver car is forced to retire before sunrise.

The crowd murmurs — Mercedes’ return has ended not in dominance, but attrition.

All eyes turn now to Ferrari, hunted only by Jaguar’s wounded D-Type.

Hamilton and Rolt refuse to surrender. Their car, slightly slower, begins to claw back seconds through sheer mechanical reliability. The Ferraris are brutal on tires and brakes; the Jaguars, smooth and economical.

Hours 17–20 (6:00 – 9:00 AM) — The Long Pursuit

The morning air is cool, the circuit drying fast. The Rolt/Hamilton Jaguar runs like a metronome, two laps down but closing. The Ferraris pit more frequently, their huge engines drinking fuel like fire.

But then, near 8 AM, disaster for Britain: the D-Type develops an oil leak. The team decides to press on, topping off at each stop, hoping the car can last to noon.

Up front, González and Trintignant press harder, their lead now fragile but real.

Hours 21–23 (9:00 – 11:00 AM) — Ferrari’s Fury

The Ferraris run wounded but unyielding. Maglioli’s sister car retires with a broken driveshaft, leaving González/Trintignant as the sole red survivor at the front.

The Jaguar, leaking oil but still thundering, remains within one lap — the closest any car has come to matching Ferrari’s might in years. The British pit wall signals “ALL OUT.” Hamilton responds with a furious final push, cutting the gap to mere minutes.

The crowd is on its feet as the clock winds down.

Hour 24 (11:00 AM – Noon) — Ferrari at Full Song

At noon, the scarlet 375 Plus crosses the line first.

José Froilán González climbs out, soaked in sweat and tears; Maurice Trintignant joins him atop the car, waving to the roaring French crowd.

Behind them, the Jaguar D-Type of Rolt and Hamilton finishes second — only three minutes behind after 24 hours, one of the narrowest margins in Le Mans history.

It is a race for the ages — power against precision, red against green, Italy against Britain.

Ferrari has conquered the day, but Jaguar has proved that the age of technology, of airflow and efficiency, has truly begun.

Aftermath & Results

Winners: José Froilán González / Maurice Trintignant — Ferrari 375 Plus

Distance: 4,088.06 km @ 170.34 km/h

Second: Tony Rolt / Duncan Hamilton — Jaguar D-Type (−3 min)

Third: Mike Hawthorn / Umberto Maglioli — Ferrari 375 Plus

Fastest Lap: Froilán González — 4′28″ (~182 km/h)

Significance:

Ferrari’s first official works victory at Le Mans.

Jaguar’s D-Type debut, proving aerodynamic design and disc brakes could nearly defeat raw power.

Mercedes’ return to Le Mans ended in retirement but laid the groundwork for its 1955 masterpiece.

The duel between González and Hamilton became legendary — raw power versus modern control — foreshadowing a decade of fierce Anglo-Italian rivalry.

Sources

Automobile Club de l’Ouest (ACO) — Official 1954 24 Heures du Mans records and lap data

Motorsport Magazine, July 1954 — “Ferrari’s Triumph and the D-Type’s Arrival”

Jaguar Heritage Trust Archives — “Birth of the D-Type: Le Mans 1954 Debut”

Ferrari Historical Archive (Maranello) — 1954 race reports and vehicle specs

Mercedes-Benz Classic Archives — “The 300SLR: Return to Le Mans 1954”

Goodwood Road & Racing — “When Red Beat Green: Ferrari vs. Jaguar, 1954”

1955 — Triumph and Tragedy

Hour 0 (4:00 PM) — The Greatest Field Ever Assembled

Saturday, June 11, 1955.

The grandstands hum with an energy Le Mans has never felt before. It is the golden age of postwar racing — and the greatest collection of cars and drivers ever gathered at the Circuit de la Sarthe.

On the grid:

Mercedes-Benz 300 SLRs, sleek silver machines with desmodromic-valve straight-eights and fuel injection, driven by Juan Manuel Fangio, Stirling Moss, Pierre Levegh, and John Fitch.

Ferrari 121 LMs, powerful but fragile V12s led by Eugenio Castellotti and Umberto Maglioli.

Jaguar D-Types, the aerodynamic British champions, now refined and faster than ever, led by Mike Hawthorn and Ivor Bueb.

Aston Martins, Porsches, Cunninghams, and Lagondas round out a field of 60 starters.

The tricolor falls. The crowd roars.

The most fateful Le Mans in history has begun.

Hour 1 (5:00 PM) — The Race of the Titans

From the first laps, it’s a three-way duel — Mercedes, Ferrari, and Jaguar trading the lead like prizefighters. Fangio and Hawthorn set a furious pace, their lap times shattering records by ten seconds.

The crowd watches in awe. The sound of engines merges into a single continuous note, echoing through the valley. Fangio’s smooth, unbroken driving seems mechanical in its perfection; Hawthorn’s, fierce and attacking.

By the end of the first hour, the silver Mercedes and green Jaguar are locked together — separated by seconds, neither yielding an inch.

Hour 2 (6:00 PM) — The Shadow of Disaster

As the second hour begins, the lead pack barrels down the pit straight once more — Fangio behind Hawthorn, with Levegh a lap down in the second Mercedes.

At 6:26 PM, everything changes.

Hawthorn, leading, suddenly pulls across the track to enter the Jaguar pit, braking hard. Behind him, Lance Macklin’s Austin-Healey swerves to avoid collision — directly into the path of Pierre Levegh’s Mercedes 300 SLR, arriving at 240 km/h.

The impact is instantaneous. The Mercedes launches over the Healey, disintegrating as it flips through the air. The magnesium body ignites in a white-hot fireball. Burning debris and engine parts rain into the crowd opposite the pit wall.

Levegh is killed instantly. More than eighty spectators lose their lives. Hundreds more are injured.

On the pit wall, Fangio sees the flash behind him — and keeps going. He has no idea of the scale of what has just occurred.

Hours 3–4 (7:00 – 8:00 PM) — Chaos and Confusion

For minutes, no one knows what to do. The French officials and ACO stewards debate halting the race, but fear that stopping would block the pit straight and hinder ambulances. They choose to continue.

Through the smoke, the race endures. The surviving Mercedes, Ferrari, and Jaguar cars continue to circulate, drivers unaware of the tragedy’s full scope. Hawthorn is visibly shaken but drives on. Moss, sharing Fangio’s car, learns of Levegh’s death only after nightfall.

In the stands, silence replaces cheers. The night begins not with applause, but with sirens.

Hours 5–8 (8:00 PM – Midnight) — The Hollow Race

As darkness descends, the cars still run — but the spirit of Le Mans is gone. The surviving Mercedes presses on under strict orders to maintain position. Fangio and Moss share brief nods, racing not to win but to uphold dignity.

The Jaguars continue at speed, their engineers urging them to stay focused. Aston Martin retires out of respect. Many privateers withdraw voluntarily.

By midnight, Hawthorn’s Jaguar leads, with Fangio’s Mercedes in pursuit — yet neither team celebrates.

Hours 9–12 (Midnight – 3:00 AM) — Death in the Shadows

The crowd has thinned. The night is unnaturally still. The drivers, one by one, learn the truth — that this is no ordinary accident. The pit crews exchange solemn looks; the ACO officials keep the press cordoned.

At 1 AM, Fitch sits alone beside the pit wall, his teammate and friend Levegh gone. He whispers a prayer before returning to duty.

Fangio drives on, relentless, his professionalism masking grief. Mercedes still holds second.

Hours 13–16 (3:00 – 6:00 AM) — Dawn of Decision

At dawn, team director Alfred Neubauer receives orders from Stuttgart: withdraw immediately after midday, regardless of position. The Mercedes engineers, many of whom helped build aircraft engines during the war, understand what this means.

They will finish with honor, not victory.

Hawthorn’s Jaguar continues in the lead. Ferrari’s challenge collapses — all works entries retire by sunrise, their engines unable to sustain the pace.

The silver Mercedes remains smooth, relentless — but empty of triumph.

Hours 17–20 (6:00 – 9:00 AM) — The Last March of Mercedes

By morning, Jaguar leads comfortably. Fangio and Moss run second, still circulating flawlessly. Neubauer prepares the signal.

At 9:00 AM, Mercedes’ pit board flashes “BOX – END”. Fangio and Moss pit together, their cars unmarked, engines cool. Mechanics close the hoods, extinguish the running lamps, and roll the cars back into the garage.

There is no ceremony, no farewell. Only quiet.

The remaining Jaguar, Ferrari privateers, and Aston Martins drive on toward an unwanted victory.

Hours 21–23 (9:00 – 11:00 AM) — The Race No One Wants to Win

Hawthorn and Bueb continue at measured pace, maintaining their lead. The crowd — subdued, grief-stricken — watches in near silence. Only the sound of engines breaks the still air.

Reporters in the pits no longer write about lap times; they write about the names of the lost. The sense of invincibility that once surrounded Le Mans has been shattered.

Hour 24 (11:00 AM – Noon) — A Quiet Flag

At noon on Sunday, the Jaguar D-Type #6 of Mike Hawthorn and Ivor Bueb crosses the finish line first. No cheers, no champagne, no waving flags. The ACO officials lower the tricolor quietly.

Hawthorn steps from the car, trembling. Bueb embraces him. Both men look haunted.

They have won the race that no one wanted to finish.

Aftermath & Results

Winners: Mike Hawthorn / Ivor Bueb — Jaguar D-Type

Distance: 4,088.06 km @ 170.34 km/h

Second: Juan Manuel Fangio / Stirling Moss — Mercedes-Benz 300 SLR (withdrawn before finish)

Third: Jacques Pollet / Maurice Genebrier — Talbot-Lago T26GS

Fastest Lap: Juan Manuel Fangio — 4′06″ (~186 km/h)

Legacy:

The 1955 Le Mans disaster remains the worst accident in motorsport history, claiming 83 lives, including Pierre Levegh.

Mercedes-Benz immediately withdrew from all motorsport, not to return until 1989.

The tragedy forced the modernization of track safety, fuel regulations, and spectator barriers worldwide.

Though Jaguar’s D-Type won, even its triumph was muted; the race’s shadow redefined what endurance truly meant.

Sources

Automobile Club de l’Ouest (ACO) — Official 1955 race report and inquiry proceedings

Mercedes-Benz Classic Archives — “1955 Le Mans: The End of Racing for Mercedes-Benz”

Motorsport Magazine, July 1955 & June 2005 retrospective issues — “The Day Racing Stopped”

Le Mans Museum Archives — “Pierre Levegh and the 1955 Catastrophe”

Goodwood Road & Racing — “1955: The Darkest Hour of Le Mans”

1956 — Healing in the Rain

Hour 0 (4:00 PM) — The Cautious Return

June 28, 1956. The Circuit de la Sarthe is changed — physically, emotionally, and philosophically.

Gone is the old pit straight that had seen horror; in its place, a newly-reprofiled start-finish line with wide runoff, new barriers, and a separate pit lane. The Automobile Club de l’Ouest has rebuilt Le Mans — not to erase the past, but to prove it can never happen again.

The entry list reflects the new world: just fifty cars instead of sixty. Gone are the vast grandstands and the towering crowds. There is quiet, and reverence.

But among those who return stands the defending champion — Jaguar, now led by Ecurie Ecosse, a small Scottish privateer team running the latest D-Type. The factory Jaguars stay home in protest of the previous year’s chaos, but the Scots arrive as standard-bearers, carrying British racing green under a blue saltire.

Opposition is fierce: Aston Martin’s DB3S, Ferrari’s 860 Monzas, Maserati’s 300S, and Talbot-Lagos. And for France, Pierre Levegh’s name hangs in the air like morning mist.

The flag drops. The world exhales. Le Mans lives again.

Hour 1 (5:00 PM) — The Spirit of the Brave

The Ferraris leap to the front, their inline-four 860 Monzas snarling on the straights. The Astons give chase — beautiful, balanced, but down on power. The Ecurie Ecosse D-Type, driven by Ninian Sanderson and Ron Flockhart, stays measured in the opening laps, running fifth. Their plan: no heroics, only precision.

By the end of the first hour, Sanderson’s calm rhythm has the blue Jaguar in third. The crowd begins to find its voice again.

Hours 2–3 (6:00–7:00 PM) — Rain on the Rebuilt Circuit

The first rain of the evening drifts in over Tertre Rouge. The circuit grows slick; Ferrari’s lead cars pirouette on their narrow tires. Sanderson’s Jaguar, with disc brakes and superior balance, glides through the storm as if made for it.

At 7 PM, an Aston Martin spins at Maison Blanche, bending a front suspension arm — a reminder that Le Mans is still a dangerous friend.

Hours 4–8 (8:00 PM – Midnight) — Night of Recovery

As dusk falls, the Ferraris and Jaguars swap the lead repeatedly. The works Ferraris, fast but delicate, require long stops for fuel and tires. The D-Type, lighter and more efficient, runs longer between refills.

Flockhart takes over at 10 PM. His smooth, unhurried driving mesmerizes onlookers — “as though he were painting rather than racing,” writes Motorsport Magazine. The Aston Martins close briefly in the wet but can’t match the Jaguars’ pace on the long Mulsanne.

By midnight, the Ecurie Ecosse car leads.

Hours 9–12 (Midnight – 3:00 AM) — Calm Under Grey Skies

The field thins through the night. Maseratis overheat, Ferraris break half-shafts, and the fragile Talbots fade. The rain returns, softer now, and the Scottish Jaguar stretches its advantage.

The second Ecurie Ecosse entry, driven by Desmond Titterington and Jack Fairman, climbs steadily to third. For the first time since 1955, Le Mans feels peaceful — a rhythm restored.

Hours 13–16 (3:00 – 6:00 AM) — Dawn of Relief

Dawn breaks pale and silent over the valley. The D-Type hums at full song, its fin slicing the fog. Sanderson and Flockhart continue to swap calmly at each stop.

The Ferraris are gone, the Astons hang on bravely, and only one Maserati remains within shouting distance. The Ecurie Ecosse team manager David Murray watches from the pit wall, raincoat buttoned tight, a small smile forming.

Hours 17–20 (6:00 – 9:00 AM) — Endurance by Discipline

The circuit is drying, the crowds returning. The blue D-Type continues to lap with uncanny precision — its straight-six engine never missing a beat. The pit board reads “P1 + 6 laps.” Murray signals: “Hold pace. No risks.”

The second Jaguar holds third. The Astons, gallant but fading, can’t match the speed or stamina of Coventry’s machines.

Hours 21–23 (9:00 – 11:00 AM) — The Scots Ascend

The final hours bring a rare sight — smiles in the pits. The rain returns lightly, soft as a benediction. Sanderson, soaked and grinning, climbs back into the car for the penultimate stint. The crowd, modest but heartfelt, applauds each pass.

At 11 AM, Flockhart takes over for the finish. The D-Type moves with quiet dignity, as if aware it carries more than victory — it carries remembrance.

Hour 24 (11:00 AM – Noon) — Triumph and Healing

The checkered flag falls.

At noon on June 29, the Ecurie Ecosse Jaguar D-Type crosses the line to win the 1956 24 Hours of Le Mans.

Ron Flockhart lifts his goggles and wipes away rain; Ninian Sanderson claps him on the shoulder. Their total distance: 3,543 kilometres at an average of 147.8 km/h — astonishing given the weather.

Behind them, the Aston Martin DB3S of Moss and Collins finishes second; the second Ecurie Ecosse Jaguar claims third. The French crowd cheers both loudly — the noise that had been missing since 1955 finally returns.

Le Mans has survived.

Aftermath & Results

Winners: Ron Flockhart / Ninian Sanderson — Jaguar D-Type (Ecurie Ecosse)

Distance: 3,543 km @ 147.8 km/h

Second: Stirling Moss / Peter Collins — Aston Martin DB3S

Third: Desmond Titterington / Jack Fairman — Jaguar D-Type (Ecurie Ecosse)

Fastest Lap: Stirling Moss (Aston Martin DB3S) — 4′23″ (~184 km/h)

Significance:

The first Le Mans under new safety regulations and a reconfigured circuit.

Ecurie Ecosse, a private Scottish team, claimed Jaguar’s third overall victory.

The D-Type’s aerodynamic form and disc brakes proved the definitive endurance package.

The race’s quiet dignity restored Le Mans’ credibility and re-ignited international confidence in endurance racing.

The blue Jaguar’s win became known as “The Race That Healed the Wound.”

Sources

Automobile Club de l’Ouest (ACO) — Official 1956 24 Heures du Mans records and race report

Jaguar Heritage Trust Archives — “Ecurie Ecosse and the D-Type’s Redemption”

Motorsport Magazine, July 1956 — “The Return of Calm to Le Mans”

Goodwood Road & Racing — “When Ecurie Ecosse Healed Le Mans”

Ecurie Ecosse Team Notes (1956 season) — Private collection, David Murray estate

1957 — The Perfect Race

Hour 0 (4:00 PM) — The Calm Before the Green Hurricane

Saturday, June 22, 1957.

Two years after tragedy, one year after recovery, Le Mans once again feels like a celebration. The circuit sparkles under clear blue skies. The rebuilt pits and grandstands gleam with fresh paint. For the first time in years, optimism hums louder than engines.

The entry list is staggering:

Ferrari 315 and 335 Sport Scagliettis, the new red titans from Maranello.

Aston Martin DBR1s, balanced and poised.

Maserati 300S, fragile but fiery.

And five privately entered Jaguar D-Types — no longer factory-backed, but still the benchmark. Among them, two cars fielded by Ecurie Ecosse, the small Scottish team that healed Le Mans in 1956.

Their drivers: Ron Flockhart, Ivor Bueb, Ninian Sanderson, and John Lawrence.

Few expect them to repeat. None imagine what’s about to happen.

The tricolor falls. The 1957 24 Hours of Le Mans begins.

Hour 1 (5:00 PM) — Red Fury

The Ferraris storm to the front, their four-cam V12s shrieking down the Mulsanne at nearly 180 mph. Mike Hawthorn, now driving for Ferrari, leads the charge. The Jaguars, smooth but slightly slower, settle into formation — fifth, sixth, seventh — all running their own pace.

From the start, the plan is discipline: short shifts, clean fuel management, and no risks. The Ecurie Ecosse pit wall signals simply: “Steady as she goes.”

By the first hour’s end, the Ferraris lead, but the blue D-Types are perfectly placed.

Hours 2–3 (6:00–7:00 PM) — Precision vs. Passion

As the sun drops lower, the Ferraris extend their lead. Their speed is ferocious, but their thirst for fuel and brakes is unrelenting. The Jaguars, by contrast, are sipping fuel and saving tires. The Dunlop discs glow briefly in braking zones, then cool almost instantly — a marvel of engineering.

By 7 PM, the lead Ferrari pits. The first Ecurie Ecosse Jaguar, #3 (Flockhart/Bueb), moves to third. The second, #15 (Sanderson/Lawrence), follows close behind. The long game is underway.

Hours 4–8 (8:00 PM – Midnight) — The Night Takes Shape

Dusk falls golden over the Sarthe. The Ferraris still lead, but the cracks begin to show. One of the 335 Sports retires with a fuel line fire; another suffers gearbox trouble.

At 10 PM, the blue Jaguars glide past into the lead. Their strategy — conserving speed and avoiding mistakes — begins to pay off. The #3 Ecurie Ecosse D-Type takes first place; the sister car moves to third. Private D-Types from Briggs Cunningham and Duncan Hamilton run in the top five.

By midnight, four of the top five cars are Jaguars.

Hours 9–12 (Midnight – 3:00 AM) — Night of the Big Cats

The night air is cool, perfect for the straight-six engines. The Jaguars hum like clockwork. Pit stops are short and flawless — refuel, quick tire check, back out. The team’s blue pit lamps flash rhythmically in the dark.

Ferrari’s last challenger, the 315S of Collins and Trintignant, begins to falter. The clutch is going. At 2 AM, the red car limps into retirement.

Le Mans has turned blue.

By 3 AM, the two Ecurie Ecosse D-Types lead — Flockhart/Bueb ahead of Sanderson/Lawrence — with private Jaguars filling the next two positions. The green and blue cars dominate the night sky, their tails flickering like comets.

Hours 13–16 (3:00 – 6:00 AM) — Dawn of Domination

The sunrise reveals what everyone now suspects: this is Jaguar’s race to lose. All Ferraris are gone. Maseratis broken. Aston Martins limping.

Flockhart continues his metronomic pace, never over-revving, never missing an apex. Bueb takes over and matches his times within tenths. The team mechanics relax slightly — even smile — something unseen in years.

The Scottish flag flutters above the pit. “Keep rhythm,” Murray signals. “She’s yours.”

Hours 17–20 (6:00 – 9:00 AM) — The Lap of Legends

By mid-morning, Jaguar’s advantage is unassailable. The Flockhart/Bueb D-Type leads by over five laps. Behind them, Sanderson and Lawrence hold second; Hamilton’s privately entered Jaguar runs third.

The only rivals left are other Jaguars. It is domination, pure and elegant.

Reporters in the pits scribble the words that will later become legend: “The night the cats hunted alone.”

Hours 21–23 (9:00 – 11:00 AM) — A Symphony of Perfection

Not a single major fault strikes the Ecurie Ecosse cars. The pit stops are mechanical poetry; the engines sing with confidence. The lead car averages nearly 180 km/h, the highest in Le Mans history to that point.

The crowd, once divided, now unites in admiration. Even Enzo Ferrari, reading the results from Maranello, later admits: “They did not win by chance. They won by mastery.”

Hour 24 (11:00 AM – Noon) — The Blue Flag of Scotland

At noon on Sunday, the chequered flag waves — and the two Ecurie Ecosse Jaguar D-Types cross the line one-two.

Flockhart and Bueb are embraced by their mechanics; Sanderson and Lawrence arrive moments later, beaming.

Behind them, privateer D-Types finish third, fourth, and sixth. Five Jaguars in the top six.

No team, before or since, has dominated Le Mans so completely.

For Britain, it’s glory. For Scotland, immortality. For Le Mans, redemption finally feels complete.

Aftermath & Results

Winners: Ron Flockhart / Ivor Bueb — Jaguar D-Type (Ecurie Ecosse)

Distance: 4,397.24 km @ 183.21 km/h (New Record)

Second: Ninian Sanderson / John Lawrence — Jaguar D-Type (Ecurie Ecosse)

Third: Jean-Marie Brussin / “Mary” (Private Jaguar D-Type)

Fourth: Duncan Hamilton / Masten Gregory — Jaguar D-Type

Fifth: Paul Frère / Freddy Rousselle — Aston Martin DBR1/300

Fastest Lap: Mike Hawthorn (Ferrari 335S) — 4′03″ (~186 km/h)

Significance:

The most dominant team result in Le Mans history — five Jaguars in the top six.

Ecurie Ecosse’s second consecutive victory, establishing them as the most successful privateer team in endurance history.

The D-Type, now at its zenith, combined aerodynamic elegance, disc brakes, and reliability into a car decades ahead of its time.

Average speeds shattered all previous records — proof that endurance racing had truly become a test of precision engineering, not survival.

It was also Jaguar’s final factory-era triumph, the culmination of Britain’s golden decade at Le Mans.

Sources

Automobile Club de l’Ouest (ACO) — Official 1957 race results, lap charts, and technical appendices

Jaguar Heritage Trust Archives — “The 1957 Le Mans Dominance: D-Type at Full Song”

Ecurie Ecosse Team Notes (1957 season) — Private collection, David Murray estate

Motorsport Magazine, July 1957 — “Jaguar’s Night of Perfection”

Goodwood Road & Racing — “Ecurie Ecosse and the Most Perfect Le Mans Win”

1958 — Ferrari’s Rain

Hour 0 (4:00 PM) — The End of the Golden Weather

June 21, 1958. The Sarthe sky is gray and heavy, the air electric with moisture. The paddock hums with nervous energy. After Jaguar’s domination of the previous year, the Coventry factory has withdrawn; the once-mighty D-Type now appears only as private entries.

In their place, a new generation has gathered — smaller teams, evolving machines:

Ferrari’s 250 TR “Testa Rossa”, the latest evolution of Maranello’s endurance lineage, led by Olivier Gendebien, Phil Hill, Mike Hawthorn, and Peter Collins.

Aston Martin’s DBR1/300, sleek and balanced but plagued by fragility.

Porsche’s 718 RSK, light and efficient, running for class glory.

Private Jaguars, Lotus, and Lotus-powered Lister Costins fill the rest.

The tricolor falls. Engines snarl through the mist. Le Mans 1958 begins — a race not of glory, but survival.

Hour 1 (5:00 PM) — The First Drops

From the start, Ferrari’s Testa Rossas set the rhythm. The scarlet 3-liter V12s pull away with astonishing pace and smoothness. Gendebien and Hill’s car (#12) leads by the first hour, the white-helmeted Phil Hill gliding through damp air as rain begins to fall in silver threads.

Behind them, the Aston Martins hold second and third, running cautiously. The private Jaguars struggle to find grip on the slick circuit.

By the end of the first hour, the rain becomes steady. The grandstands shimmer under umbrellas.

Hours 2–3 (6:00–7:00 PM) — The Rain Deepens

The circuit turns treacherous. Cars slide helplessly through Arnage and Indianapolis. The Ferraris, nimble and rear-biased, dance delicately; the heavier Aston Martins begin to aquaplane.

At 6:45 PM, Moss loses control of the #5 Aston Martin while lapping slower traffic. The car spins twice before striking the barrier. Moss is unhurt but furious — their main challenger is out.

By 7 PM, the Ferrari of Hill and Gendebien has already built a one-lap advantage. The Testa Rossa’s reliability, its hand-beaten aluminum body, and its perfect weight balance give it a near-mystical grace in the wet.

Hours 4–8 (8:00 PM – Midnight) — The Rain Never Stops

As night falls, the downpour grows heavier. It is relentless — the kind of rain that seeps into overalls, gloves, and souls. The Ferraris continue serenely, while others falter.

Aston Martin loses a second car with gearbox failure; Porsche’s nimble RSKs climb steadily up the order, safe from attrition by virtue of lightness. Private Jaguar D-Types fall like dominoes — one to aquaplaning, another to fire.

At midnight, only 30 cars remain. The Ferrari #12 of Hill and Gendebien leads comfortably, followed by the Aston Martin of Salvadori/Shelby, and a private 250 TR driven by Seidel/Behra.

The rhythm of the rain drowns even the engines.

Hours 9–12 (Midnight – 3:00 AM) — The Long Drown

The rain persists, unbroken. Mechanics huddle under tarps; spectators sleep in soaked coats. The pit straight glows under floodlights, reflecting a thousand blurred images.

Inside the leading Ferrari, Hill drives with methodical perfection — his wipers beating in time with each downshift. Gendebien replaces him, driving with quiet artistry through the mist. Their lap times differ by mere seconds — a rare harmony between two masters.

Behind them, Aston Martin’s hopes finally die. Shelby’s car retires before 2 AM with clutch failure. The Ferraris now run first, second, and fourth.

By dawn, even the rain begins to respect them.

Hours 13–16 (3:00 – 6:00 AM) — Dawn of Endurance

The first grey light finds the circuit drenched and exhausted. The Testa Rossa of Hill/Gendebien still leads, unchallenged. Every corner, every shift, every refuel is a lesson in discipline.

The Aston Martins are gone, the Jaguars spent, the Maseratis broken. Porsche alone still presses on, its tiny 1.5-litre RSK holding fourth overall — a triumph of simplicity amid ruin.

At 5 AM, Hill hands over to Gendebien with a small smile: “Keep her safe. The rest are gone.”

Hours 17–20 (6:00 – 9:00 AM) — The Race of Attrition

By morning, the rain finally begins to fade, but the damage is done. Out of fifty starters, only twenty-two cars remain. The Ferrari of Hill and Gendebien continues to lead by twelve laps — an eternity at Le Mans.

Their only rival, the Seidel/Behra Ferrari, spins at Arnage and limps to the pits, damaged.

The American-entered Lotus retires. The circuit, now streaked with puddles and oil, is a graveyard of ambition.

Ferrari’s engineers, exhausted and soaked, whisper prayers more than strategy.

Hours 21–23 (9:00 – 11:00 AM) — The Final March

The final hours are mercifully dry. Gendebien’s Testa Rossa runs flawlessly, its body streaked with mud and oil. Hill stands by the pit wall, drenched but smiling faintly — a testament to endurance, not speed.

The Porsches continue to climb — the small white RSKs humming unbroken — while every surviving British entry struggles.

The rain begins to fall again, softly, as if to escort the race home.

Hour 24 (11:00 AM – Noon) — Triumph in the Rain

At noon, the Ferrari 250 Testa Rossa of Phil Hill and Olivier Gendebien crosses the finish line. The crowd erupts — not in thunderous joy, but in admiration. The little V12 has survived everything: the rain, the night, and the ghosts of the past.

It is a triumph of endurance and engineering, not power.

Ferrari has reclaimed Le Mans — and begun an era of dominance.

Behind them, the private Ferrari of Seidel/Behra finishes second; Porsche’s RSK claims an astonishing third overall.

Le Mans 1958 belongs to the rain, to Ferrari, and to the quiet perfection of two men who refused to falter.

Aftermath & Results

Winners: Phil Hill / Olivier Gendebien — Ferrari 250 Testa Rossa (Works)

Distance: 4,101.926 km @ 170.33 km/h

Second: Wolfgang Seidel / Edgar Barth — Ferrari 250 TR (Private)

Third: Jean Behra / Hans Herrmann — Porsche 718 RSK

Fastest Lap: Stirling Moss (Aston Martin DBR1/300) — 4′17″ (~188 km/h)

Significance:

Ferrari’s first official overall victory at Le Mans since 1954.

The 250 Testa Rossa became the definitive endurance machine — elegant, balanced, indomitable.

Phil Hill’s first Le Mans win, marking the start of his partnership with Gendebien that would define the next era.

The rain and attrition transformed Le Mans 1958 into a test of survival rather than speed — only 12 finishers classified.

The success of Porsche’s 718 RSK foreshadowed the brand’s endurance legend to come.

Sources

Automobile Club de l’Ouest (ACO) — Official 1958 race results and weather logs

Ferrari Historical Archive (Maranello) — “The Triumph of the 250 Testa Rossa”

Motorsport Magazine, July 1958 — “The Race Drowned in Glory”

Goodwood Road & Racing — “Rain, Resilience, and the Birth of the Testa Rossa Legend”

Porsche Museum Stuttgart — “718 RSK: The Small Car That Survived the Storm”

1959 — Britain’s Finest Hour

Hour 0 (4:00 PM) — Green Hope

Saturday, June 20, 1959.

The circuit lies under clear skies and a light Atlantic breeze. For the first time in years, Le Mans feels dry, bright, and fast. The paddock brims with expectation: could this finally be Aston Martin’s year?

At the front of the grid sit:

Aston Martin DBR1/300, refined to perfection after years of heartbreak, driven by Carroll Shelby, Roy Salvadori, Stirling Moss, and Jack Fairman.

Ferrari 250 TR Testa Rossa, the reigning champion, fielded by Gendebien/Hill, Trintignant/Behra, and Allison/Bianchi.

Porsche 718 RSK, light and precise, chasing the Index of Performance.

Private Jaguar D-Types and Listers, proud remnants of a fading dynasty.

The tricolor falls, and the field explodes toward Dunlop. Shelby’s Aston snarls past the pits — Le Mans 1959 is underway.

Hour 1 (5:00 PM) — The Duel of Red and Green

From the start, it’s a sprint. Moss hurls the DBR1 into the lead, setting lap records with surgical precision. Behind him, the Ferraris snap at his heels, the wail of twelve cylinders chasing the deeper note of Aston’s straight-six.

By the end of the first hour, Moss and Salvadori’s #5 car leads narrowly from the Ferrari of Hill/Gendebien. Both pit crews already know: this will not be a race of attrition — it will be a fight for speed.

Hours 2–3 (6:00–7:00 PM) — Ferrari Strikes

At 6 PM, Gendebien takes the lead on raw pace, the Testa Rossa’s V12 howling down Mulsanne at 180 mph. Aston Martin’s team manager, John Wyer, signals Moss to hold steady. The British cars can’t match Ferrari’s power, but their fuel economy and balance are unmatched.

When Moss pits for fuel, Ferrari stretches its advantage. Yet inside the green garage, the confidence remains — Wyer’s plan is to win with consistency, not fireworks.

Hours 4–8 (8:00 PM – Midnight) — The Long Game Begins

As twilight deepens, Aston Martin’s patience starts to pay off. The Ferraris, fast but heavy on brakes and fuel, stop often. The DBR1s run long and clean. Shelby takes over from Moss and begins clawing back time with steady, tire-saving laps.

At 10 PM, the Gendebien/Hill Ferrari pits with overheating brakes. The lead swings back to Aston. Moss’s sister car, #6, rises to second.

By midnight, Aston Martins run 1–2, with the Ferraris three laps behind. The pit wall message reads: “Perfect. Maintain rhythm.”

Hours 9–12 (Midnight – 3:00 AM) — British Precision in the Night

The night is clear, moonlit, and kind — ideal for the DBR1’s breathing straight-six. The Ferraris fight back briefly, but their brakes glow cherry red into Mulsanne Corner.

Salvadori takes the lead car and drives like a man in meditation — each downshift exact, each line clean. Shelby stands beside the pit wall, nodding silently.

At 2 AM, the Aston’s lead stretches to four laps. Only Porsche’s nimble 718s seem immune to fatigue, running like clockwork far down the order.

Hours 13–16 (3:00 – 6:00 AM) — The Test of Heart

Ferrari’s challenge collapses at dawn. The Trintignant/Behra car blows its engine at Arnage; Gendebien’s Testa Rossa, still second, loses third gear. The red pits fall silent.

By sunrise, Aston Martin’s #5 leads by eight laps. Moss’s car (#6) is second, but team orders soon arrive — hold position, protect the lead.

Shelby and Salvadori agree without argument. Their mission is no longer to race, but to bring Aston Martin home.

Hours 17–20 (6:00 – 9:00 AM) — Calm Command

Morning light glints off the DBR1’s polished bonnet. Wyer’s plan unfolds perfectly. Both Astons run within seconds of each other, lap after lap, as if tethered by invisible wire.

Ferrari’s final car retires with a seized gearbox at 8 AM. The race is now Britain’s alone.

The crowd senses it too — the return of the green cars to supremacy, the culmination of a decade’s dream.

Hours 21–23 (9:00 – 11:00 AM) — The Last Push

Shelby climbs back in for his final stint. He is exhausted, pale, but determined. The Texan pushes hard enough to maintain rhythm without tempting fate. “No glory laps,” Wyer warns. “Just bring her home.”

Behind them, the Porsches of Barth/Frère and Maglioli/Behra fight for third, their small engines buzzing like bees behind the bellow of Aston’s straight-six.

At 11 AM, the team chalkboard shows DBR1 #5 + 10 laps. The pits go quiet except for the rhythmic tick of the stopwatch.

Hour 24 (11:00 AM – Noon) — Victory for Britain

As the clock strikes noon, Carroll Shelby coasts the #5 Aston Martin under the chequered flag. Roy Salvadori waves from the pit wall, overcome.

Aston Martin has done it — its first and only overall win at Le Mans.

The second DBR1 of Moss/Fairman finishes second, cementing a historic 1–2.

John Wyer folds his arms, finally allowing himself a smile. After years of heartbreak, British endurance racing stands atop the world.

Aftermath & Results

Winners: Carroll Shelby / Roy Salvadori — Aston Martin DBR1/300

Distance: 4,347 km @ 181.2 km/h

Second: Stirling Moss / Jack Fairman — Aston Martin DBR1/300

Third: Jean Behra / Hans Herrmann — Porsche 718 RSK

Fastest Lap: Stirling Moss (Aston Martin DBR1) — 3′59″ (~185 km/h)

Significance:

Aston Martin’s first and only outright Le Mans victory, crowning its decade of development.

The win completed a rare double: Le Mans and the World Sports-Car Championship.

Carroll Shelby’s greatest drive before heart problems ended his racing career — paving the way for his legendary second act as a constructor.

Stirling Moss, though second, set the race’s fastest lap and validated the DBR1 as Britain’s greatest sports car.

The triumph marked the end of the 1950s British golden age — Jaguar, Aston Martin, and privateers at their peak before Ferrari’s 1960s empire began.

Sources

Automobile Club de l’Ouest (ACO) — Official 1959 24 Heures du Mans reports and lap charts

Aston Martin Heritage Trust Archives — “DBR1: The Victory of 1959”

Motorsport Magazine, July 1959 — “Aston Martin’s Perfect Endurance”

Goodwood Road & Racing — “Shelby, Salvadori, and Britain’s Finest Hour”

Ferrari Archivio Storico — Internal competition bulletins (1959 season)

Porsche Museum Stuttgart — “718 RSK: The Giant-Killer of Le Mans ’59”

1960 — The Red Empire Begins

Hour 0 (4:00 PM) — The Changing of the Guard

Saturday, June 25, 1960.

The air over the Sarthe shimmers with heat. For the first time since the war, the sound of twelve-cylinder Ferraris drowns out all else. Aston Martin’s factory team has withdrawn, Jaguar’s D-Type era is gone, and Porsche’s new mid-engined cars hum quietly in the background.

At the front of the grid gleam Ferrari 250 TR 59/60s, their blood-red bodies smoother, lower, and more disciplined than the year before. Leading the charge:

Olivier Gendebien and Paul Frère, the Belgian pairing regarded as endurance racing’s finest duo.

Phil Hill / Wolfgang von Trips, Ferrari’s factory spearhead.

Willy Mairesse / Ricardo Rodríguez, the future embodied.

Challenging them:

Porsche 718 RSK prototypes from Stuttgart, tiny and precise.

Maserati Tipo 61 “Birdcage”, fragile brilliance from Modena’s other house.

Lotus 15s and private D-Types, nostalgic yet outclassed.

The tricolor falls. The Ferraris leap forward as one — a red storm rolling into the future.

Hour 1 (5:00 PM) — A Ferrari Formation Flyer

The first hour is surgical domination. Phil Hill establishes an unrelenting rhythm — 4-minute laps, perfect lines, fuel measured to the drop. Behind him, Porsche’s Bonnier/Herrmann RSK runs valiantly, but the difference in straight-line speed is brutal: Ferrari exceeds 175 mph on Mulsanne; Porsche barely reaches 155.

By the end of the hour, Ferrari holds the top four positions. Gendebien/Frère settle comfortably into second. The temperature rises to 31 °C. Engines cook. Tyres blister. The first Maserati is gone before 5:30.

Hours 2–3 (6:00–7:00 PM) — Discipline vs Defiance

Ferrari’s pit wall under Romolo Tavoni is a study in control. No shouts, no panic. Just hand signals, stopwatches, and note-books.

The private Jaguars and Lotuses, desperate to stay relevant, push too hard. At 6:40 PM, the Lister-Jaguar of Cunningham spins at Arnage. By 7 PM, the British challenge is over.

The Ferraris run one-two-three in formation, each exactly thirty seconds apart — a red ballet across the Sarthe.

Hours 4–8 (8:00 PM – Midnight) — Precision in Twilight

As dusk melts into indigo, the Ferraris settle into endurance mode. Gendebien takes the lead from Hill after a flawless pit stop. Their consistency is unreal — the 250 Testa Rossa’s 3.0-litre V12 running like a metronome at 7,200 rpm.

At 9 PM, light rain begins to mist the track, but it’s brief — a gift for the Italians, who relish cool engines and clean air. The Porsches gain ground in the mixed conditions, climbing into the top five on efficiency alone.

By midnight, the leaderboard reads:

1️⃣ Gendebien/Frère (Ferrari 250 TR)

2️⃣ Hill/von Trips (Ferrari 250 TR)

3️⃣ Mairesse/Rodríguez (Ferrari 250 TR)

4️⃣ Bonnier/Herrmann (Porsche RSK)

5️⃣ Behra/Gregory (Maserati Birdcage)

The new decade has its hierarchy — and Maranello sits firmly on top.

Hours 9–12 (Midnight – 3:00 AM) — Red in the Dark

The night is clear, the crowd serene. The Ferraris glide like phantoms through the mist. Frère’s measured driving keeps the lead car’s average speed above 180 km/h, while Hill’s sister machine maintains pressure just in case.

At 1:30 AM, Behra’s Maserati retires with broken suspension. Porsche inherits third. For the first time, a 1.6-litre car runs on the overall podium — a quiet sign of the future.

At 3 AM, Gendebien hands back to Frère. The Belgian engineer-driver combination runs flawlessly, every lap within three seconds of the last.

Hours 13–16 (3:00 – 6:00 AM) — The Belgian Morning

Dawn comes gold and soft. The air is cool, perfect for Ferraris. The Gendebien/Frère car stretches its lead to three laps. Tavoni signals, “Conservare” — conserve.

Hill’s car drops time with a slipping clutch but remains second. Porsche’s Bonnier/Herrmann hold third, the RSK chirping steadily past Maison Blanche like a metronome in silver.

By 6 AM, the Ferraris lead by over 30 minutes. Nothing seems able to touch them.

Hours 17–20 (6:00 – 9:00 AM) — The Red March

As morning warms, attrition claims the rest. Aston privateers fall out with gearbox trouble, Maseratis scatter their fragile frames. Only the Ferraris remain pristine.

Gendebien drives with glacial calm, Frère with the precision of an engineer drafting a line. They are unstoppable. The Porsches climb to third and fifth on reliability alone — small victories amid the Italian tide.

At 9 AM, Hill’s car suffers a gearbox seizure at Arnage. Out. The empire loses one of its kings, but the crown remains secure.

Hours 21–23 (9:00 – 11:00 AM) — The Final Chorus

Ferrari’s pit is silent but for the rhythmic hiss of fuel pumps. The red cars circulate endlessly. The Belgian car now leads by seven laps over the remaining Ferrari of Mairesse/Rodríguez, itself seven ahead of Porsche.

Frère refuses to slow excessively — he knows mechanical sympathy comes from constancy, not hesitation. Every downshift perfect, every brake application identical.

At 11 AM, Gendebien takes the wheel for the final stint. The crowd rises as he passes each lap, the 12-cylinder note steady and serene.

Hour 24 (11:00 AM – Noon) — Ferrari Ascendant

At exactly noon, the red 250 Testa Rossa crosses the line.

Olivier Gendebien raises his fist once, modestly; Paul Frère smiles beneath his goggles.

Ferrari has won Le Mans 1960 — its second straight, and the first of five consecutive triumphs that will define an era.

Behind them, the sister Ferrari finishes second, Porsche third, completing a podium that marks both the present and the future of endurance racing.

The British green is gone. The Italian red reigns.

Aftermath & Results

Winners: Olivier Gendebien / Paul Frère — Ferrari 250 Testa Rossa (Works)

Distance: 4,417 km @ 183.3 km/h

Second: Willy Mairesse / Ricardo Rodríguez — Ferrari 250 Testa Rossa (Works)

Third: Jo Bonnier / Hans Herrmann — Porsche 718 RSK

Fastest Lap: Phil Hill (Ferrari 250 TR) — 3′57″ (~187 km/h)

Significance:

Ferrari’s first in a record-setting five-year streak (1960–64).

The Gendebien/Frère partnership became the benchmark of calm professionalism — their drives defined the art of endurance.

Porsche’s podium marked the arrival of the small-capacity revolution, previewing the mid-engined future.

1960 was also the final Le Mans for the traditional front-engined prototype — the end of an era before aerodynamics and rear-mid layouts rewrote the rulebook.

Sources

Automobile Club de l’Ouest (ACO) — Official 1960 24 Heures du Mans Results & Lap Charts

Ferrari Archivio Storico (Maranello) — “Le Mans 1960: Gendebien & Frère”

Motorsport Magazine, July 1960 — “Ferrari’s Measured Mastery”

Goodwood Road & Racing — “The Beginning of Ferrari’s Empire”

Porsche Werk Weissach Archives — “718 RSK: Podium in the Shadow of Giants”

1961 — The Calm Before the Storm

Hour 0 (4:00 PM) — Red Dawn