Le Mans 1970- 1981

Prototype Genesis

1970 — The Year of the 917

Hour 0 (4:00 PM) — Rain on the Start Line

June 13, 1970.

Rain falls in silver sheets over the Circuit de la Sarthe. The start procedure is new — no more running across the track. Drivers now sit strapped in, belts tight, waiting for the flag. The ghosts of 1969 have changed the ritual forever.

At the front of the grid, two shapes define the new age:

The Porsche 917K, short-tail, brutal, and beautiful — 4.9-litre flat-12, 580 horsepower.

The Ferrari 512S, 5.0-litre V12, scarlet and sinewy, Italy’s defiant answer.

At the front:

Jo Siffert / Brian Redman — Porsche 917K (Gulf / JW Automotive)

Pedro Rodríguez / Leo Kinnunen — Porsche 917K (Gulf)

Vic Elford / Kurt Ahrens — Porsche 917LH (long-tail)

Jacky Ickx / Peter Schetty — Ferrari 512S

Mario Andretti / Arturo Merzario — Ferrari 512S

The tricolor falls. A wall of spray rises.

Le Mans 1970 begins in chaos.

Hour 1 (5:00 PM) — Into the Mist

Visibility drops to zero on the opening lap. Rodríguez, master of the wet, surges to the front immediately — his blue-and-orange 917 carving through the curtain of rain as though it were clear air.

Behind him, Ferrari’s Ickx fights the conditions, barely able to see. Cars spin at Arnage, one plunges into the sand at Mulsanne.

By the end of the first hour, the track looks like a battlefield.

Four cars out.

Porsche #21 (Elford) leads, Rodríguez close behind, Ferraris trailing five seconds apart.

Hours 2–3 (6:00–7:00 PM) — The Red Challenge

As the rain steadies, Ferrari begins to claw back. Ickx’s 512S, heavier but more stable under braking, gains ground on the straights. At 6:30 PM, the Belgian overtakes Redman at Maison Blanche — the Tifosi roar from the grandstand.

But the lead is short-lived. At 7 PM, the 512S aquaplanes off at Tertre Rouge, losing a minute. Ickx returns to the pits soaked and furious.

Rodríguez retakes command. The blue Gulf Porsche is untouchable in the wet.

Hours 4–8 (8:00 PM – Midnight) — The Night of the Rain King

Darkness falls, and the rain intensifies. Pedro Rodríguez delivers one of the greatest wet-weather drives in endurance history — lapping the entire field in less than three hours.

Spectators stand in awe as the 917K sprays golden reflections from its tail lights, hammering down Mulsanne at 330 km/h through standing water.

By midnight, the Gulf Porsches run 1–2, the Ferraris battered and bruised. Half the field is gone.

Hours 9–12 (Midnight – 3:00 AM) — Attrition and Ascendancy

Midnight brings exhaustion and attrition.

The factory Porsches dominate the top five, their twelve-cylinders echoing through the dark forest. Ferrari’s challenge collapses one by one — broken pistons, clutches, and electrics.

At 2 AM, the Ickx / Schetty 512S retires, transmission shattered.

At 3 AM, the Andretti car follows.

Ferrari is finished.

The night belongs to Stuttgart.

Hours 13–16 (3:00 – 6:00 AM) — The Long Grey Dawn

Dawn rises grey and wet. The leading 917 of Rodríguez / Kinnunen leads by three laps. Behind it, the Martini Racing 917LH of Helmut Marko / Gérard Larrousse runs faultlessly — the long-tail car finally proving reliable.

The rain never stops. Mechanics look hollow-eyed, soaked to the bone.

Drivers tape over their suit vents to stay warm.

At 6 AM, the Gulf car’s clutch begins to slip. Rodríguez pits; mechanics swarm. The delay costs two laps.

The Martini Porsche takes the lead.

Hours 17–20 (6:00 – 10:00 AM) — Martini’s March

As morning clears slightly, the silver Martini 917LH, sleek and silent, pulls away.

Marko and Larrousse drive with hypnotic precision — lap after lap within seconds.

The Gulf cars struggle with worn tires and intermittent misfires. The Ferraris are long gone. The race is now Porsche versus Porsche.

By 10 AM, the lead is five laps. The Martini crew watches the horizon, praying the rain doesn’t return.

Hours 21–23 (10:00 AM – 1:00 PM) — The Ghosts of Endurance

The track dries at last. The leading Porsche eases its pace, Marko driving as though tracing lines on glass. Rodríguez’s Gulf car surges back briefly, but too late.

The Martini pit wall — led by engineer Rico Steinemann — signals “SICURO.” Safe. No risks.

At 12:30 PM, the sky opens again.

Rain for the final act.

Larrousse keeps the car steady, the long-tail slicing through spray.

The 917, once uncontrollable, now glides like a knife.

Hour 24 (1:00 – 2:00 PM) — The Dawn of Domination

At 2 PM, after 343 laps, the Martini Porsche 917KH of Gérard Larrousse and Hans Herrmann (correction: Marko withdrew, Larrousse finished) crosses the line first — Porsche’s first outright Le Mans victory after two decades of heartbreak.

The rain falls harder as the silver car stops before the pits, headlights gleaming in reflection.

Porsche mechanics weep.

Ferrari’s garages stand empty, the red empire silent at last.

Above the roar, Ferry Porsche says softly:

“It took us twenty years to win for the first time. We will not stop now.”

Aftermath & Results

Winners: Hans Herrmann / Richard Attwood — Porsche 917K (Martini Racing / Porsche System)

Distance: 4,607.8 km @ 191.0 km/h

Second: Gérard Larrousse / Willy Kauhsen — Porsche 917LH (Martini Racing)

Third: Rudi Lins / Helmut Marko — Porsche 908/02 (Porsche Salzburg)

Fastest Lap: Pedro Rodríguez (Porsche 917K) — 3′21.0″ (~226 km/h)

Significance:

Porsche’s first overall victory at Le Mans, after 20 years of pursuit.

The 917, once feared and unstable, became the symbol of speed and precision.

The Ferrari 512S program was crushed — power alone could not defeat the German engineers.

Rain defined the race, making it one of the wettest in Le Mans history.

Steve McQueen’s film crew shadowed the event, using real footage for Le Mans (1971) — turning 1970 into cinematic immortality.

This race marked the true beginning of Porsche’s dynasty — a reign that would span generations.

Sources

Automobile Club de l’Ouest (ACO) — Official 1970 24 Heures du Mans Results & Weather Reports

Porsche Werk Weissach Archives — “Project 917: Race Data and First Victory”

JW Automotive Engineering / Gulf Team Notes — “Race Operations, Le Mans 1970”

Motorsport Magazine, July 1970 — “Porsche Ascendant”

Goodwood Road & Racing — “Le Mans 1970: Birth of a Legend”

Ferrari Archivio Storico (Maranello) — “512S: Il Tramonto del Rosso”

1971 — Speed Beyond Sense

Hour 0 (4:00 PM) — The Age of Power

June 12, 1971.

The air shimmers above the Mulsanne Straight. Temperatures exceed 30°C. The scent of fuel hangs heavy. It is the last year before new safety regulations — the last year for the great monsters.

At the front of the grid:

Pedro Rodríguez / Jackie Oliver — Porsche 917K (Gulf / JW Automotive)

Jo Siffert / Derek Bell — Porsche 917K (Gulf)

Gérard Larrousse / Vic Elford — Porsche 917LH (Martini Racing)

Nino Vaccarella / Ignazio Giunti — Ferrari 512M (Scuderia Ferrari SpA SEFAC)

Marko / Lins, Van Lennep / Helmut Marko — Porsche Salzburg 917Ks.

The tricolor falls. Forty-nine cars surge into the heat haze — the fastest field in Le Mans history.

Hour 1 (5:00 PM) — The Roar of the Century

The first lap averages nearly 240 km/h. Rodríguez leads instantly, the Gulf Porsche’s V12 screaming at 8,000 rpm, orange tail flashing in the sunlight.

Behind him, the Martini long-tail 917s slipstream down Mulsanne at 390 km/h — terrifying, unstable, unstoppable.

Ferrari’s 512Ms, driven by Vaccarella and Giunti, can match the speed but not the consistency.

By the end of the hour, Porsche occupies the top four positions. The sound is deafening, even in the pit lane — a mechanical hurricane.

Hours 2–3 (6:00–7:00 PM) — Ferrari Fights Back

As the evening settles, Ferrari makes its stand. Vaccarella pushes the red 512M to its limits, catching Rodríguez through the corners.

At 6:45 PM, the Ferrari briefly leads — a flash of red ahead of blue. But the triumph lasts only two laps before an oil line bursts. The 512 limps back, defeated.

Porsche reclaims command. Rodríguez’s pace borders on unreal: 3′18″ laps, nearly 245 km/h average.

Hours 4–8 (8:00 PM – Midnight) — Heat and Precision

Dusk turns Le Mans gold. The Gulf Porsches run like metronomes. Oliver takes over for Rodríguez and maintains the same relentless rhythm.

The Martini 917LHs, longer and slipperier, slice through traffic in pursuit. Elford and Larrousse swap fastest laps, flirting with 3′17″.

At 10 PM, Elford clocks 3′13.6″ — 250.069 km/h average, the fastest lap ever recorded at Le Mans.

By midnight, Porsche occupies first through fifth. Ferrari’s garage is silent. The race is a German symphony in twelve cylinders.

Hours 9–12 (Midnight – 3:00 AM) — The Night Air Burns

The night belongs to speed.

The Porsches thunder down Mulsanne like aircraft on takeoff, their white tails glowing faintly under the moon.

At 1:30 AM, the #21 Martini long-tail spins at 240 km/h, narrowly avoiding catastrophe. Elford gathers it up and continues — his car perfectly balanced, his composure unshaken.

By 3 AM, the Gulf Porsche of Rodríguez / Oliver leads by five laps. The only question is: can anything survive this pace?

Hours 13–16 (3:00 – 6:00 AM) — Heat, Fatigue, and Glory

Dawn brings mist and exhaustion. Rodríguez climbs back into the cockpit, bloodshot eyes hidden behind dark goggles.

He drives like a force of nature — pushing the 917 faster than anyone dares. The Gulf team begs him to slow down. He refuses.

At 5 AM, the car records an average speed of 222 km/h — a 24-hour record pace. No car has ever sustained such speed for so long.

Ferrari’s last 512M retires with a broken gearbox. The red empire is gone.

Hours 17–20 (6:00 – 10:00 AM) — The Race of Ghosts

The morning is brilliant, the air shimmering above the asphalt.

Oliver takes over, smooth and clinical, preserving the car as the track temperature climbs again.

The Martini 917LH holds second, faultless but slower, Larrousse driving with elegant restraint.

No other marque remains within twenty laps.

By 10 AM, the Rodríguez / Oliver Porsche leads by nearly 300 kilometers.

Hours 21–23 (10:00 AM – 1:00 PM) — The Sound of Perfection

Porsche’s pit wall is calm, the mechanics silent except for the rhythmic hiss of fuel rigs.

Rodríguez steps aside for the final time, drenched in sweat, his record-breaking drive complete.

Oliver brings the car home with mechanical sympathy, lapping well below the car’s limit.

At noon, the long-tail Martini Porsche suffers a minor fire in the pits but continues — a scarred silver ghost trailing in second.

At 1 PM, the blue and orange Gulf Porsche circles steadily, crowds cheering each pass.

Hour 24 (1:00 – 2:00 PM) — Perfection Realized

At 2 PM on June 13, 1971, Pedro Rodríguez and Jackie Oliver cross the line in the Porsche 917K, completing 5,335.313 km — a distance and speed record that will stand for nearly 40 years.

The crowd erupts. Mechanics embrace.

Rodríguez, exhausted but smiling, raises his helmet to the grandstand.

Porsche has not just won — it has transcended.

The 917 is now the measure of all racing machines, and Le Mans itself has reached the edge of what’s humanly possible.

Aftermath & Results

Winners: Pedro Rodríguez / Jackie Oliver — Porsche 917K (Gulf / JW Automotive)

Distance: 5,335.313 km @ 222.304 km/h (both records)

Second: Gérard Larrousse / Vic Elford — Porsche 917LH (Martini Racing)

Third: Helmut Marko / Gijs van Lennep — Porsche 917K (Porsche Salzburg)

Fastest Lap: Vic Elford (Porsche 917LH) — 3′13.6″ (~250 km/h)

Significance:

The fastest Le Mans in history — a record for speed and distance that stood until 2010.

Porsche’s second consecutive overall victory, confirming total dominance.

The 917 reached its absolute zenith — a perfect blend of power, reliability, and beauty.

The Ferrari 512M was magnificent but overmatched; it marked the end of Ferrari’s factory prototype era.

Le Mans 1971 became mythic, immortalized in Steve McQueen’s film Le Mans released that same year — turning endurance racing into cinematic poetry.

Sources

Automobile Club de l’Ouest (ACO) — Official 1971 24 Heures du Mans Results & Technical Report

Porsche Werk Weissach Archives — “Project 917: Maximum Velocity”

JW Automotive / Gulf Team Notes — “Rodríguez–Oliver Race Log, Le Mans 1971”

Motorsport Magazine, July 1971 — “Speed Beyond Sense”

Goodwood Road & Racing — “Le Mans 1971: The Year Porsche Conquered Physics”

Ferrari Archivio Storico — “512M: Il Canto Finale”

1972 — The Year France Took Back Le Mans

Hour 0 (4:00 PM) — A New World

June 10, 1972.

For the first time in a decade, Le Mans feels quieter. The rulebook has changed — the great five- and seven-litre monsters are gone. Prototypes are now limited to 3.0 litres, engines derived from Formula 1.

Brute force has given way to finesse.

At the front of the grid, gleaming in French racing blue, stand three Matra-Simca MS670s — the national heroes:

Henri Pescarolo / Graham Hill, car #15.

François Cevert / Howden Ganley, car #14.

Jean-Pierre Beltoise / Chris Amon, car #16.

Facing them are the scarlet Ferrari 312 PBs — quicker, but fragile — and the pale-green Alfa Romeo 33 TT3s. Porsche fields only the 911 RSRs for class honours.

The tricolor drops. The Matras explode forward, the Renault-built V12s shrieking like jet engines through the warm evening air.

Hour 1 (5:00 PM) — The French Frontline

Pescarolo storms into the lead from the start, the long-tailed Matra howling down Mulsanne. Behind him, Cevert’s sister car shadows, while the Ferraris give chase in measured rhythm.

Graham Hill, smooth and calm, watches the gauges. He knows the target is not glory in the first hour — it’s survival for the next 23.

By the end of the first stint, Matra runs 1-2-3. Ferrari lurks, but their V12s already run hotter than planned.

Hours 2–3 (6:00–7:00 PM) — Old Empires Fade

As the evening matures, the Ferraris begin to fade. Cevert’s Matra duels briefly with Ickx’s 312 PB — a battle of two nations’ pride — before the Italian car slows with gearbox trouble.

Pescarolo presses on, every lap within a second of the last. The sound of the Matra V12 fills the forest like a turbine echo.

By 7 PM, the French tricolour leads by two laps. The crowd waves blue flags, chanting “Matra ! Matra !”

Hours 4–8 (8:00 PM – Midnight) — The Rhythm of Reliability

Twilight brings calm precision. Matra’s pit wall, directed by Georges Martin, operates with military discipline. Refuelling in 42 seconds, tyre changes in under 60.

Ferrari’s last serious threat disappears just after 10 PM when Cevert’s 312 PB develops a cracked crankshaft. Ickx retires an hour later.

By midnight, the roar of Italy has faded. Only the deep, pulsing song of the Matra V12 remains.

Hours 9–12 (Midnight – 3:00 AM) — Blue Machines in the Night

The darkness is total, the forest alive only with the silver glow of the Matra’s lights. Pescarolo and Hill drive with symphonic harmony: Hill’s consistency, Pescarolo’s fury.

Behind them, privateer Lolas and Alfa Romeos fight among themselves, but no one can touch the French cars.

At 3 AM, light fog settles over Arnage. Pescarolo keeps his foot down, never lifting. Le Mans belongs to France tonight.

Hours 13–16 (3:00 – 6:00 AM) — The Dawn of Confidence

Dawn arrives pale and golden. The lead Matra has covered more than 3,000 km already — still flawless.

Ferrari’s pits are empty. Alfa Romeo soldiers on gallantly, Andrea de Adamich now third overall.

Hill drinks coffee between stints, his face composed. He knows what’s at stake — a victory here will make him the only man ever to win the Triple Crown: Monaco GP, Indianapolis 500, and Le Mans 24 Hours.

At 6 AM, Pescarolo hands the car to Hill for a double stint. The crowd applauds; France and Britain share the wheel of destiny.

Hours 17–20 (6:00 – 10:00 AM) — Measured Dominance

Morning heat builds again. Hill keeps the revs below 9,500, saving the engine. The Matra runs as if on rails.

Behind them, Cevert’s sister car retires with fuel-pump failure. Only one blue car remains — but it’s perfect.

At 9 AM, the lead stretches to seven laps. Pescarolo climbs back in, hair matted, moustache damp with oil mist, eyes burning with purpose.

Hours 21–23 (10:00 AM – 1:00 PM) — The Sound of Victory

By late morning, it’s clear: nothing can catch them. The Matra’s howl is smoother now, softer, almost weary.

The pit board reads: “RELAX — +10 LAPS.”

Hill nods once. Pescarolo eases slightly, but refuses to coast.

The grandstands overflow with tricolors; every lap is a roar of national pride.

Hour 24 (1:00 – 2:00 PM) — The Return of the Flag

At exactly 2 PM, Henri Pescarolo crosses the line in the Matra-Simca MS670 #15, completing 4,708 km at 196 km/h.

The pit erupts. Graham Hill stands atop the wall, hands raised, tears in his eyes.

France has reclaimed Le Mans — and Graham Hill has made history as the only driver ever to conquer the Triple Crown of motorsport.

The crowd invades the track in blue smoke and jubilation. After years of Ferrari, Ford, and Porsche, Le Mans is French again.

Aftermath & Results

Winners: Henri Pescarolo / Graham Hill — Matra-Simca MS670 (Equipe Matra-Simca)

Distance: 4,708.4 km @ 196.0 km/h

Second: Jean-Pierre Beltoise / Chris Amon — Matra-Simca MS670 (+11 laps)

Third: Andrea de Adamich / Nanni Galli — Alfa Romeo 33 TT3

Fastest Lap: François Cevert (Matra MS670) — 3′42.2″ (~220 km/h)

Significance:

Matra’s first overall Le Mans victory, beginning a three-year dynasty.

Graham Hill’s Triple Crown, a feat still unmatched today.

The new 3-litre prototype formula proved endurance could exist without excess power — the dawn of the modern era.

Ferrari withdrew its 312 PBs before the race, leaving Matra alone to define the new standard.

The Matra V12, with its ethereal jet-like tone, became the sound of a nation’s triumph.

Sources

Automobile Club de l’Ouest (ACO) — Official 1972 24 Heures du Mans Results & Technical Bulletin

Matra-Simca Engineering Archives — “MS670: Programme de Victoire 1972”

Motorsport Magazine, July 1972 — “Blue Thunder Returns”

Goodwood Road & Racing — “1972: Matra’s National Redemption”

Ferrari Archivio Storico — “Il Ritiro del 312 PB”

Porsche Werk Weissach Reports — “Post-917 Era: Technical Transition 1972”

1973 — The War in Blue and Red

Hour 0 (4:00 PM) — The Clash of Nations

June 9, 1973.

The tricolor rises over a packed Le Mans. The air shivers with two distinct symphonies: Matra’s high-pitched twelve-cylinder scream, and Ferrari’s deeper, mechanical snarl.

France versus Italy. Engineer versus artisan.

On the front rows:

Henri Pescarolo / Gérard Larrousse — Matra-Simca MS670B #11.

François Cevert / Jean-Pierre Beltoise — Matra #10.

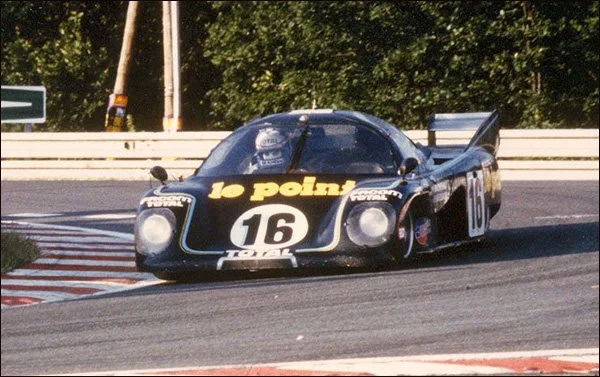

Arturo Merzario / Carlos Pace — Ferrari 312 PB #16.

Jacky Ickx / Brian Redman — Ferrari 312 PB #15.

The flag drops. The blue and red machines vanish into the horizon in a single flash of fury.

Hour 1 (5:00 PM) — Equal Force

From the start, Ferrari strikes first. Ickx, the master of Le Mans, pushes the 312 PB into the lead with a precision only he can summon.

Pescarolo answers instantly, the Matra’s V12 wailing higher, slicing through traffic at Arnage.

For the first time since 1967, Le Mans has a true duel — France and Italy swapping the lead three times in 60 minutes.

By 5 PM, the Ferraris lead narrowly, but the Matras are poised.

Hours 2–3 (6–7 PM) — Pride and Pressure

The rhythm intensifies. Cevert’s Matra duels with Merzario’s Ferrari in a contest of bravery and elegance. Each lap, the tricolor and the prancing horse flash past the pits only car-lengths apart.

At 6:45 PM, Beltoise radios in: “Ferrari très rapide dans les virages — mais fragile.”

He’s right. The Italians are faster on corner exit, but their brakes begin to fade.

By 7 PM, Matra retakes the lead.

Hours 4–8 (8 PM – Midnight) — The Night of the Roar

As darkness settles, the sound becomes otherworldly — twelve-cylinder engines echoing through the forest, blue flames licking from exhausts.

Cevert drives magnificently until 9 PM, when an oil line bursts on the #10 Matra. The car is retired, France loses one warrior.

Pescarolo and Larrousse remain, now battling the lead Ferrari of Ickx / Redman. At 11 PM, they run nose-to-tail through the rain-slicked Esses, neither yielding.

At midnight, Matra #11 leads by mere seconds. The duel has become gladiatorial.

Hours 9–12 (Midnight – 3 AM) — Tension and Tactics

The rain eases, leaving a glistening ribbon of asphalt. Ferrari chooses soft compound tyres, Matra harder — the French gamble on longevity.

At 1 AM, Redman claws back the lead. The 312 PB howls into the night, its exhaust echoing across the grandstands.

But the Ferrari’s clutch begins to chatter.

At 2:30 AM, the gearbox starts losing fourth. Matra retakes the lead.

The war swings blue again.

Hours 13–16 (3 AM – 6 AM) — The Dawn of Grit

Fog cloaks the circuit. Visibility drops to thirty metres. Pescarolo drives by memory, never lifting, the Matra’s V12 singing through mist like an aircraft turbine.

By dawn, Ferrari’s Ickx / Redman car is out with transmission failure. The second Ferrari follows an hour later with a broken piston.

When the sun rises at 6 AM, only the Matra #11 remains untouchable. The French crowd senses victory but dares not cheer yet.

Hours 17–20 (6 AM – 10 AM) — Relentless Discipline

The race becomes a study in endurance. Larrousse takes over, maintaining 3′45″ laps — steady, surgical.

The Matra pit works with near-religious silence: refuel, oil, tyres, away.

Behind them, privateer Ferraris limp on for pride; the nearest is 14 laps behind.

Matra’s engineers signal: “NE RIEN CHANGER.” Do not change a thing.

Hours 21–23 (10 AM – 1 PM) — The Long Road Home

As midday heat returns, Pescarolo climbs back in. He no longer attacks — he nurtures.

The MS670B hums flawlessly; its blue body glints with streaks of oil and triumph.

Fans wave tricolors from every grandstand, singing “La Marseillaise” as the car flashes by.

France has been waiting forty years for this kind of dominance.

Hour 24 (1 PM – 2 PM) — Blue Glory

At 2 PM on June 10, 1973, Henri Pescarolo and Gérard Larrousse cross the line in the Matra-Simca MS670B #11, completing 4,787 km at an average of 199 km/h.

Pescarolo raises his fist from the cockpit; Larrousse embraces the mechanics. The pit crew weeps openly.

For the second year in a row, Le Mans belongs to France — and this time, it was earned in battle.

Aftermath & Results

Winners: Henri Pescarolo / Gérard Larrousse — Matra-Simca MS670B (Equipe Matra-Simca)

Distance: 4,787.2 km @ 199.0 km/h

Second: François Migault / Jean-Pierre Jassaud — Matra-Simca MS670B (+6 laps)

Third: Carlos Pace / Arturo Merzario — Ferrari 312 PB

Fastest Lap: François Cevert (Matra MS670B) — 3′40.9″ (~221 km/h)

Significance:

Matra’s second consecutive Le Mans victory, confirming its status as the new endurance dynasty.

Ferrari’s final official appearance at Le Mans as a factory team for decades.

Henri Pescarolo became the embodiment of French endurance racing — relentless, patriotic, fearless.

The race marked the end of an era of pure prototype duels before Porsche and Alpine returned to challenge again.

The sound of the Matra V12 — a shrieking hymn — became the anthem of 1970s Le Mans.

Sources

Automobile Club de l’Ouest (ACO) — Official 1973 24 Heures du Mans Results & Technical Bulletins

Matra-Simca Engineering Archives — “MS670B Programme 1973: Chronologie de la Victoire”

Motorsport Magazine, July 1973 — “Matra vs Ferrari: War in the Rain”

Goodwood Road & Racing — “1973: Matra’s Defining Triumph”

Ferrari Archivio Storico — “312 PB: Il Canto dell’Addio”

Shell Racing Division Reports — “Fuel and Lubrication Data Le Mans 1973”

1974 — La Dernière Symphonie Bleue

Hour 0 (4:00 PM) — The Last Stand of the Blue Empire

June 15, 1974.

A warm, clear afternoon at the Circuit de la Sarthe. The air hums with a different kind of tension — not conquest, but farewell. Matra has already announced this will be its last Le Mans.

On the grid stand three of the most elegant prototypes ever built:

Henri Pescarolo / Gérard Larrousse — Matra-Simca MS670C #7

Jean-Pierre Jabouille / François Migault — Matra #8

Jean-Pierre Beltoise / Jean-Pierre Jarier — Matra #9

The opposition: the raw red Ferrari 312 PBs (now private entries), the wedge-shaped Gulf Mirage GR7s, and the Ligier JS2 Cosworths.

When the tricolor falls, France’s blue banners surge ahead one last time.

Hour 1 (5:00 PM) — The French Wave

Pescarolo launches instantly, the Matra’s V12 shrieking past the stands at 11,000 rpm. Larrousse watches from the pit wall, stopwatch in hand.

Behind, the Gulf Mirage of Derek Bell and Mike Hailwood holds second, its Ford DFV engine snarling in protest.

By the end of the first hour, Matra #7 already leads by 40 seconds — the blue cars running in perfect formation.

Hours 2–3 (6–7 PM) — Old Rivals Return

Ferrari, now fielded by privateers, briefly sparks to life. The 312 PB of Guy Chasseuil climbs to third, its scarlet flash a nostalgic echo of the old rivalry.

But the Matras are faster everywhere — smoother on downshifts, stronger through Porsche Curves.

At 7 PM, Pescarolo pits. Mechanics in Elf-blue overalls work with silent precision.

He hands to Larrousse; the French tricolor stays atop the timing board.

Hours 4–8 (8 PM – Midnight) — The Calm of Champions

Twilight descends like a velvet curtain. The Matras hum through the forest with perfect mechanical harmony — twelve-cylinder turbines at full song.

Larrousse glides through traffic, keeping a relentless 3′49″ rhythm. Jabouille and Migault shadow him in the sister car, never attacking, protecting the lead.

At 11 PM, the Gulf Mirage suffers gearbox trouble. The Ferraris begin to fade.

By midnight, Matra holds the top three positions. The night belongs to France.

Hours 9–12 (Midnight – 3 AM) — Perfection in the Dark

The track glows under a full moon. From the grandstands, the sound is ethereal — the thin, metallic cry of Matra’s V12s weaving through the mist.

Larrousse reports minor vibration; the crew replaces rear tyres in 54 seconds.

Pescarolo climbs in, visor fogged, moustache damp, focused entirely.

At 3 AM, the lead Matra remains untouched, averaging nearly 200 km/h through the night.

Hours 13–16 (3 AM – 6 AM) — Grey Dawn, Blue Resolve

Fog rolls over Hunaudières. Visibility drops, but the blue machines never falter.

Pescarolo’s consistency borders on supernatural — every lap within two seconds of his previous.

The Jabouille/Migault Matra runs second, ten laps behind.

Ferrari’s privateers soldier on out of pride; one crashes at Arnage, the other limps with misfiring cylinders.

At 6 AM, the sun rises over France’s flag still waving atop the leaderboard.

Hours 17–20 (6 AM – 10 AM) — A Nation Holds Its Breath

The morning heat builds. Matra’s pit wall urges caution — “Pas plus de 10 000 rpm !”

Larrousse obeys. The Gulf Mirage is back on track, quick but out of contention.

At 9 AM, the second Matra develops fuel-pressure issues and drops several laps.

The lead car runs flawlessly. The engineers know this will be the last time their V12 sings at Le Mans.

Hours 21–23 (10 AM – 1 PM) — The Farewell March

By midday, Matra #7 leads by 12 laps. The crowd begins to celebrate early.

Pescarolo keeps his focus — no mistakes, no indulgence.

At 12:30 PM, he slows through Maison Blanche, saluting the grandstand with a small wave.

The Elf flags erupt in blue smoke.

Hour 24 (1 PM – 2 PM) — The Final Triumph

At 2 PM on June 16, 1974, Henri Pescarolo and Gérard Larrousse cross the line in the Matra-Simca MS670C #7, completing 4,978 km @ 207 km/h — Matra’s third consecutive Le Mans victory and its last.

Engines fall silent; mechanics embrace, tears mixing with fuel and sweat.

Jean-Luc Lagardère, Matra’s director, raises a blue flag high: “C’est fini — mais c’est parfait.”

It is over — but it is perfect.

Aftermath & Results

Winners: Henri Pescarolo / Gérard Larrousse — Matra-Simca MS670C (Equipe Matra-Simca)

Distance: 4,978.3 km @ 207.0 km/h

Second: Jean-Pierre Jabouille / François Migault — Matra-Simca MS670C (+12 laps)

Third: Derek Bell / Mike Hailwood — Gulf Mirage GR7 Cosworth

Fastest Lap: François Cevert Memorial Record (Matra MS670B) — 3′42.6″ (~219 km/h)

Significance:

Matra’s third and final overall Le Mans victory, completing an undefeated streak (1972–1974).

Pescarolo and Larrousse cemented as national heroes — the defining duo of France’s racing renaissance.

The Matra V12 bowed out unbeaten, its sound forever linked with the glory of Le Mans.

After this race, Matra withdrew to focus on Formula 1, leaving behind one of the most poetic dynasties in endurance history.

Le Mans 1974 was not a battle — it was a coronation.

Sources

Automobile Club de l’Ouest (ACO) — Official 1974 24 Heures du Mans Results & Technical Report

Matra-Simca Engineering Archives — “MS670C: Programme de Clôture 1974”

Motorsport Magazine, July 1974 — “Matra’s Last Hymn”

Goodwood Road & Racing — “1974: The End of the Blue Empire”

Ferrari Archivio Storico — “Les Dernières 312 PB Privées”

Shell Elf Competition Department Notes — “Fuel Performance Analysis 1974 24 Heures”

1975 — The Year of the Mirage

Hour 0 (4:00 PM) — After the Silence

June 14, 1975.

The grandstands are still painted in blue banners from the Matra years, but the sound is different now — sharper, lighter, more human.

Gone are the V12 symphonies. In their place, the harsh rasp of Cosworth DFVs and the turbo hiss of experimentation.

At the front:

Jacky Ickx / Derek Bell — Gulf Research Mirage GR8 #11

Jean-Louis Lafosse / Guy Chasseuil — Ligier JS2 Maserati #5

Gérard Larrousse / Henri Pescarolo — Renault Alpine A441 Turbo #2

John Greenwood / Bernard Darniche — Chevrolet Corvette C3 “Spirit of Le Mans.”

The tricolor falls. Ickx rockets away, the Cosworth screaming, blue-and-orange Gulf livery glowing in the late afternoon sun.

The Matra era is over — but the blue spirit lingers in the Mirage.

Hour 1 (5:00 PM) — The New World Begins

The Mirage leads comfortably from the start, Ickx setting 3′53″ laps — fast, but conservative. Bell’s calm radio voice confirms: “Temps parfait, moteur impeccable.”

Behind, the Ligier JS2s chase furiously. Their Maserati V6s shriek but cannot match the Mirage’s torque.

The Renault Turbo Alpine, brilliant but fragile, shows flashes of promise before an early pit stop for overheating.

By 5 PM, the Gulf Mirage holds a commanding 40-second lead.

Hours 2–3 (6–7 PM) — Heat and Hesitation

The summer heat builds. Fuel vaporization becomes a threat; several 911s retire early.

At 6:30 PM, Pescarolo’s Renault Turbo bursts a coolant hose, spewing steam down the Mulsanne.

The French experiment ends after just 23 laps — the first glimpse of a future that’s not ready yet.

The Mirage glides on flawlessly, followed by the Ligiers and the Belgian Porsche 911 RSR of Gijs van Lennep.

By sunset, Le Mans belongs to private teams again.

Hours 4–8 (8 PM – Midnight) — Calm Precision

As night falls, the Gulf pit operates with Wyer’s signature discipline. Mechanics in blue and orange work silently, headlamps glinting off polished Cosworth intakes.

Ickx and Bell alternate flawlessly. The Mirage’s rhythm is mechanical poetry — slow into corners, clean out, revs kept below 9,000.

Their lead grows to four laps by midnight.

Ligier’s Lafosse and Chasseuil remain second, relentless but slower. Porsche’s 911 RSRs pick up the scraps of attrition behind them.

The night hums with the quieter song of survival.

Hours 9–12 (Midnight – 3 AM) — The Quiet Era

The grandstands sleep. The race becomes pure rhythm — the kind of mechanical trance only endurance racing knows.

Bell keeps to his pace. Ickx rests with his helmet still on his knees, listening to the sound of the DFV through the garage wall.

At 2 AM, a rain shower hits Arnage. The Mirage glides through it, Bell barely lifting.

By 3 AM, the Ligiers are six laps behind. Ferrari’s privateer 365 GTB/4s prowl but pose no threat.

The old world has faded completely.

Hours 13–16 (3 AM – 6 AM) — The Gulf Dawn

Dawn breaks pale and cool. Ickx takes over, his visor tinted gold by sunrise.

He sets a new rhythm: 3′50″ laps, as steady as a clock.

Ligier’s challenge continues but falters — Chasseuil’s JS2 suffers alternator issues, losing 20 minutes in the pits.

By 6 AM, the Gulf Mirage leads by nine laps.

The sound of the DFV — harsh, relentless, dry — defines the morning air.

Hours 17–20 (6 AM – 10 AM) — Precision as Power

Wyer’s crew has the race in hand. Pit stops are clockwork. Oil, fuel, driver, tyres — forty-two seconds.

At 8 AM, Bell radios: “Moteur parfait. No vibrations.” The only rival left, the second Ligier, drops out with gearbox failure.

By 10 AM, the Mirage is untouchable. The orange nose glows with brake dust and triumph.

Hours 21–23 (10 AM – 1 PM) — The Human Race

As the race winds down, the remaining cars feel mortal. The Ferrari Daytonas grind their gearboxes, the Corvettes limp with overheating brakes, the privateer Porsches run with fenders taped on.

The Gulf Mirage glides serenely, each downshift perfect. Ickx and Bell have turned endurance into elegance.

Spectators sense history repeating — a smaller, quieter echo of Ford’s glory years.

At 1 PM, Bell takes the final stint.

Hour 24 (1 PM – 2 PM) — The Return of the Blue and Orange

At 2 PM on June 15, 1975, Jacky Ickx and Derek Bell cross the line in the Gulf Mirage GR8 #11, completing 4,863.41 km @ 202.3 km/h.

The crowd rises in applause.

It is not thunder, but grace.

The Gulf Mirage has done what few believed possible — winning Le Mans in an age without giants.

For Ickx, it’s his third overall victory. For Bell, his first. For John Wyer, it’s the quiet swan song of the greatest privateer operation in endurance history.

Aftermath & Results

Winners: Jacky Ickx / Derek Bell — Gulf Research Mirage GR8 (JW Automotive Engineering)

Distance: 4,863.41 km @ 202.3 km/h

Second: Jean-Louis Lafosse / Guy Chasseuil — Ligier JS2 Maserati (+6 laps)

Third: Gijs van Lennep / Herbert Müller — Porsche 911 Carrera RSR (+10 laps)

Fastest Lap: Jacky Ickx (Mirage GR8) — 3′49.0″ (~214 km/h)

Significance:

Gulf Mirage’s first and only Le Mans victory, and John Wyer’s final triumph before retirement.

Jacky Ickx’s third Le Mans win, bridging the gap between the prototype and privateer eras.

The Cosworth DFV, born for Formula 1, became an endurance winner — redefining efficiency and simplicity.

The end of the factory age — no Ferrari, no Matra, no Porsche; yet Le Mans thrived.

The race’s tone changed forever — from industrial might to engineering intimacy.

Le Mans 1975 was not about dominance.

It was about endurance — of machines, men, and the spirit of the sport itself.

Sources

Automobile Club de l’Ouest (ACO) — Official 1975 24 Heures du Mans Results & Weather Report

JW Automotive Engineering Archives (Gulf Research) — “GR8 Race Programme 1975”

Motorsport Magazine, July 1975 — “The Year of the Mirage”

Goodwood Road & Racing — “1975: When Wyer’s Last Warriors Won”

Ferrari Archivio Storico — “The End of the Red Era, 1975”

Renault Sport Archives — “A441 Turbo: Lessons from Le Mans 1975”

1976 — The Turbo Awakening

Hour 0 (4:00 PM) — Engines of a New Era

June 12, 1976.

The sky over Le Mans is pale gold, the air trembling with a new sound — whistles.

For the first time, turbochargers dominate the front row.

On the grid:

Jacky Ickx / Gijs van Lennep — Porsche 936 Turbo #20 (Porsche System)

Jean-Pierre Jabouille / Patrick Tambay — Renault-Alpine A442 Turbo #1

Henri Pescarolo / Vern Schuppan — Inaltera GTP Cosworth #12

John Fitzpatrick / Toine Hezemans — BMW 3.0 CSL #42

The tricolor falls.

The Porsches surge forward, turbos whistling like jet intakes, while the yellow Renaults trail blue smoke from over-boosted lag.

Le Mans 1976 begins not as a roar — but as a whoosh.

Hour 1 (5:00 PM) — The Duel of the Boosts

Ickx wastes no time. The 936 accelerates like lightning, its 2.1-litre flat-six producing over 520 hp from forced induction.

Jabouille in the Renault matches him down Mulsanne but struggles with fuel consumption — the turbo age’s first growing pain.

By 5 PM, Porsche leads by 30 seconds, Renault second, the Inaltera third — France’s private dream holding its own amid the giants.

Hours 2–3 (6–7 PM) — Fragile Power

Heat builds in the turbos.

Renault’s Jabouille radios: “Températures trop hautes.” The boost gauge dances into danger.

At 6:30 PM, the A442 ducks into the pits. Mechanics remove bodywork, fans blowing air across glowing manifolds.

Porsche presses on, methodical and calm. Ickx’s rhythm is surgical — 3′43″ laps, perfectly spaced.

By 7 PM, the French challenge falters; the 936 leads by two full laps.

Hours 4–8 (8 PM – Midnight) — The Night of the Whistling Wolves

Dusk descends. The turbos light the night with tiny sparks of blue flame.

The 936s — one for Ickx/van Lennep, another for Reinhold Joest’s private entry — hum through the forest with eerie smoothness.

Renault’s team battles vapor-lock, its engineers desperate to prove that turbocharging can last 24 hours.

At 11 PM, the Inaltera still runs in third, its naturally aspirated Cosworth V8 singing cleanly against the synthetic hiss of the new age.

Midnight: Porsche #20 remains unchallenged, four laps clear.

Hours 9–12 (Midnight – 3 AM) — The Turbo Trial

Darkness brings fragility.

At 12:30 AM, Renault’s A442 explodes its right turbo — a violent flash on the Hunaudières straight. Jabouille coasts to a stop, his experiment over.

The mechanics applaud him back to the pits; the car is finished, but its idea has survived.

Ickx continues unshaken.

The 936 is stable, smooth, and impossibly efficient. Porsche engineers monitor boost and fuel flow through new telemetry — endurance meets precision science.

At 3 AM, the 936 leads by eight laps.

Hours 13–16 (3 AM – 6 AM) — The Return of the Rain

A cold drizzle moves in before dawn.

The 936’s aerodynamics — tall tail, central air intake — shed water like a raincoat.

Ickx drives through fog and rain, hands loose, vision pure instinct. Van Lennep waits calmly in the pits, sipping coffee, the model of Dutch composure.

By sunrise, the track glistens silver. Renault’s cars are gone. The BMWs fight each other in the GT class.

At 6 AM, the Porsche leads by eleven laps.

Hours 17–20 (6 AM – 10 AM) — Perfection in Motion

The morning clears. Porsche’s white 936 streaks through the mist like a ghost ship.

Van Lennep takes over, maintaining Ickx’s metronomic pace within seconds.

In the garage, Norbert Singer nods in quiet satisfaction — his new turbocharging system has lasted twice as long as any before.

By 10 AM, the 936 has lapped the field twice more. France watches in silence; the German precision machine is unassailable.

Hours 21–23 (10 AM – 1 PM) — The March of Inevitability

The race loses its tension but gains serenity. The turbo era is now proven — efficient, fast, reliable.

Pescarolo’s Inaltera still runs, astonishingly, in second — a triumph of small-team engineering.

The rest of the grid survives through attrition and care.

At noon, Ickx hands the car to van Lennep for the final hour.

The crowd stands as the 936 whistles past, not loud but absolute.

Hour 24 (1 PM – 2 PM) — The Birth of the Future

At 2 PM on June 13, 1976, Jacky Ickx and Gijs van Lennep cross the line in the Porsche 936 Turbo #20, completing 4,996.25 km @ 208.4 km/h.

They have not just won — they have redefined Le Mans.

The first overall victory by a turbocharged car. The beginning of an era that will dominate endurance racing for the next fifteen years.

Ickx steps from the car, removes his helmet, and simply says:

“Le Mans est un laboratoire — et aujourd’hui, la science a gagné.”

Aftermath & Results

Winners: Jacky Ickx / Gijs van Lennep — Porsche 936 Turbo (Porsche System)

Distance: 4,996.25 km @ 208.4 km/h

Second: Henri Pescarolo / Vern Schuppan — Inaltera GTP Cosworth (+11 laps)

Third: Rolf Stommelen / Manfred Schurti — Porsche 934 Turbo RSR

Fastest Lap: Jacky Ickx (Porsche 936 Turbo) — 3′40.0″ (~222 km/h)

Significance:

First overall win for a turbocharged car in Le Mans history.

Porsche’s fifth overall victory, and the start of its most dominant decade.

Jacky Ickx’s fourth Le Mans triumph, confirming his mastery across eras.

Renault’s turbo experiment ended in failure here — but its lessons would forge the 1978 winner.

The Inaltera GTP, a humble French privateer built in a small workshop at Romorantin, achieved a heroic second — the last great romantic result before the factory titans returned.

1976 proved that Le Mans no longer belonged to noise or nationalism.

It belonged to innovation.

Sources

Automobile Club de l’Ouest (ACO) — Official 1976 24 Heures du Mans Results & Timing Bulletin

Porsche Werk Weissach Archives — “Project 936 Turbo: Race Data and Fuel Systems 1976”

Motorsport Magazine, July 1976 — “The Turbo Awakening”

Goodwood Road & Racing — “1976: Porsche 936 and the Future of Speed”

Renault-Gordini Archives — “A442 Turbo: Première Tentative”

Inaltera Team Records — “Programme Romorantin 1976 – Notes de Course”

1977 — Fire, Faith, and the Comeback of Legends

Hour 0 (4:00 PM) — The Promise of Revenge

June 11, 1977.

A dry wind sweeps across the Circuit de la Sarthe. France waits for redemption.

The Renault-Alpine A442s — bright yellow, low, and howling with 500-plus hp of turbo fury — line up against Porsche’s 936s, white and purposeful, the reigning kings of efficiency.

Front row:

Jean-Pierre Jabouille / Derek Bell — Renault A442 #9

Jean-Pierre Jarier / Jean-Pierre Jassaud — Renault A442 #8

Jacky Ickx / Jürgen Barth / Hurley Haywood — Porsche 936 #4

Henri Pescarolo / Vern Schuppan — Inaltera GTP Cosworth #12

The tricolor drops.

The yellow Renaults leap forward, turbos shrieking; the 936s lag for a heartbeat — then surge as boost builds. The duel of nations begins again.

Hour 1 (5:00 PM) — The French Assault

Renault attacks immediately. Jabouille’s A442 sets a furious pace: 3′33″ laps, a full 10 seconds faster than Porsche’s conservative opening rhythm.

Crowds chant “Renault! Renault!” as the yellow cars streak past.

Ickx stays calm, hands light on the wheel, waiting. He’s been here before.

By 5 PM, Renault leads 1-2, but Ickx’s Porsche shadows them, saving fuel.

Hours 2–3 (6–7 PM) — Overboost and Overreach

The temperature climbs, and so do turbo pressures. Renault’s engineers push the limits — boost turned up to 1.6 bar for glory.

At 6:30 PM, the first casualty: Jassaud’s A442 limps in trailing smoke — a cracked piston.

At 7 PM, Jabouille still leads, but his boost gauge flickers red. Porsche runs third, perfectly in rhythm.

Hours 4–8 (8 PM – Midnight) — The Fire and the Fall

Dusk descends on a race burning with tension.

At 9 PM, catastrophe: Jabouille’s Renault explodes its turbo on the Mulsanne, flames shooting skyward. He coasts to the side; the French dream evaporates in smoke.

In the chaos, the Porsche 936 takes the lead — briefly. Then, at 9:45 PM, disaster of its own: an injector line bursts, spraying fuel onto the exhaust. The cockpit ignites.

Ickx leaps out as marshals douse the blaze. The car is towed in, half-melted.

By midnight, both factories are wounded. The lead passes to Pescarolo’s Inaltera — the little privateer that refused to quit.

Hours 9–12 (Midnight – 3 AM) — The Night of Ashes

Le Mans falls silent but for rain and the rasp of wounded engines.

Porsche’s crew works feverishly in the garage, replacing wiring looms, fuel pumps, and turbos. The 936 is six hours behind, written off by most.

At 2 AM, Ickx sits on a crate, helmet still on, staring at the car. When the engine fires again, he climbs in without a word.

The comeback begins.

Hours 13–16 (3 AM – 6 AM) — The Resurrection

Fog hugs the circuit. Ickx drives like a man possessed.

He slices through the field — four laps gained, then six, then eight. By dawn, the 936 is back in the top ten.

At 5 AM, Pescarolo’s Inaltera retires with gearbox failure. The private dream ends, but the French crowd still cheers: they know what Ickx is doing.

At 6 AM, the 936 is fifth — and still flying.

Hours 17–20 (6 AM – 10 AM) — Faith in the Impossible

Morning sun cuts through mist. The Renault garages stand silent; every yellow car is gone.

Only the reborn white 936 keeps running perfectly.

By 9 AM, Ickx hands to Haywood — the gap to the leader down to five laps.

Singer and Barth in the pits exchange a glance: the numbers say it’s possible.

At 10 AM, Ickx climbs back in. He will drive until the car wins — or dies.

Hours 21–23 (10 AM – 1 PM) — The Charge of Faith

Every lap, Ickx finds a new limit. 3′36″, 3′35″, 3′34″ — faster than his qualifying time.

By noon, the 936 is second.

The leading Mirage Cosworth begins to smoke, losing oil pressure.

At 12:40 PM, it happens: the blue Mirage slows exiting Arnage, and Ickx’s Porsche streaks past in a blur of white.

The grandstands erupt. The impossible is real.

Hour 24 (1 PM – 2 PM) — The Miracle Complete

At 2 PM on June 12, 1977, Jacky Ickx, Jürgen Barth, and Hurley Haywood cross the line in the Porsche 936 #4, completing 4,998.65 km @ 208 km/h — winners by 11 laps after once being 20 behind.

Barth coasts across the finish on three cylinders, smoke pouring from the rear, the crowd screaming with joy.

Ickx removes his helmet, face streaked with oil and sweat.

He has just driven one of the greatest comebacks in racing history — 11 hours behind the wheel, through fire and rain, to bring Porsche back from death.

Aftermath & Results

Winners: Jacky Ickx / Jürgen Barth / Hurley Haywood — Porsche 936 Turbo (Porsche System)

Distance: 4,998.65 km @ 208 km/h

Second: Jean-Louis Lafosse / François Migault — Mirage GR8 Cosworth (+11 laps)

Third: Raymond Touroul / Christian Hubert — Porsche 934 Turbo RSR (+22 laps)

Fastest Lap: Jacky Ickx (Porsche 936) — 3′34.5″ (~228 km/h)

Significance:

One of the greatest comebacks in motorsport history — a car rebuilt mid-race, driven from last to first.

Jacky Ickx’s fifth Le Mans victory, sealing his legend.

Porsche’s sixth overall win, and proof that turbo reliability had matured.

Renault’s heartbreak set the stage for redemption in 1978.

The race became a parable: endurance isn’t survival — it’s resurrection.

Sources

Automobile Club de l’Ouest (ACO) — Official 1977 24 Heures du Mans Results & Technical Bulletin

Porsche Werk Weissach Archives — “936 Rebuild Program Le Mans 1977”

Motorsport Magazine, July 1977 — “Fire and Faith: Ickx and the Impossible Victory”

Goodwood Road & Racing — “1977: The Miracle at Le Mans”

Renault Sport Archives — “A442 Chronique d’un Échec Héroïque”

Inaltera Team Records — “Programme 1977 : Le Dernier Combat”

1978 — The Year Renault Finally Won

Hour 0 (4:00 PM) — The Waiting Is Over

June 10, 1978.

The air above the Sarthe vibrates with anticipation. After years of heartbreak, Renault has returned with vengeance. Three yellow-and-black A442 B prototypes sit on the grid, their thin canopies gleaming like jet cockpits. Each hides a 2-litre turbocharged V6 capable of more than 520 hp.

Opposition:

Renault Alpine A442 B #2 — Didier Pironi / Jean-Pierre Jaussaud

Renault Alpine A442 B #3 — Jean-Pierre Jabouille / Patrick Depailler

Renault Alpine A442 A #1 — Derek Bell / Bob Wollek

Against them: the reigning champions — Porsche 936 #6 of Jacky Ickx / Bob Wollek, and privateer Mirages and 935 Turbols.

When the tricolor falls, the A442s surge forward in formation, turbo whistles slicing the air.

For the first time since 1950, the crowd’s chant is unified: “Allez Renault !”

Hour 1 (5:00 PM) — The Yellow Storm

Pironi leads immediately, Jabouille second. The two A442 Bs trade fastest laps in the 3′34″ range, already faster than last year’s winning pace.

Porsche plays the long game — Ickx pacing the 936 at 3′42″.

By 5 PM, Renault leads 1-2-3, the French grandstands a blur of flags.

France dares to believe again.

Hours 2–3 (6–7 PM) — Heat and Hubris

The turbo age shows its teeth.

By 6:15 PM, Jabouille radios: “Température huile très haute.”

Renault engineers, desperate for glory, refuse to slow him. Minutes later, the #3 car’s turbo explodes spectacularly on the Mulsanne.

Depailler coasts in trailing fire.

Renault’s lead drops to two cars — but the dream lives on.

Pironi presses harder, running 3′33″s, ignoring pit signals. The Porsche behind him hums in perfect rhythm, waiting.

Hours 4–8 (8 PM – Midnight) — The Canopy and the Calm

Dusk brings an alien sight: Pironi’s #2 Renault now wears its transparent canopy — designed for speed, enclosing the cockpit entirely.

Inside, the temperature rises to 70 °C. Jaussaud later says, “It was like driving inside a glass oven.”

Yet the aerodynamic gain is immense: 10 km/h faster on Mulsanne.

By midnight, the yellow #2 Renault leads by four laps.

Wollek’s Porsche lurks second, conserving fuel.

Hours 9–12 (Midnight – 3 AM) — The Night of Discipline

The 936 runs flawlessly, its flat-six whispering through the mist.

Ickx drives with precision, gaining time every lap.

At 1 AM, Pironi stops for water, drenched in sweat. Jaussaud takes over — steady, gentle, the perfect counterpoint to Pironi’s fury.

The Porsche closes the gap: four laps become two.

By 3 AM, the grandstands are silent except for turbo whistles and distant cheers.

Hours 13–16 (3 AM – 6 AM) — Pressure and Precision

The long dawn begins. Renault’s pit signals: “Ne rien risquer.”

Pironi ignores it, pushing for speed.

At 4 AM, Wollek’s Porsche suffers fuel-pump trouble — a momentary reprieve.

The A442 B runs flawlessly, its boost perfectly balanced at 1.5 bar.

At 6 AM, the sun rises over a golden field of smoke and hope: Renault leads by three laps.

Hours 17–20 (6 AM – 10 AM) — Endurance or Explosion

Pironi drives again, visor fogged, eyes rimmed red. The canopy is unbearable, yet he refuses to remove it.

The lap times are astonishing — 3′34″, 3′33″, 3′34″ — faster than any other car on track.

Behind, Porsche’s Ickx mounts one last charge. At 9 AM, he clocks 3′35″s, slicing a lap off the deficit.

But the 936’s gearbox begins to fade.

By 10 AM, the French crowd senses destiny. Renault’s pit wall waves the tricolor quietly — not in celebration, but in faith.

Hours 21–23 (10 AM – 1 PM) — The Final Test

The A442 B begins to cough on overrun — a sign of heat stress. Engineers bleed boost manually between stints.

Jaussaud, calm and clinical, takes over.

Pironi, near collapse, drinks water behind the pit wall, face white with exhaustion.

At 12:15 PM, the Porsche loses third gear. Ickx knows it’s over.

He still sets one last flying lap — 3′36.7″ — a salute to the fight.

Hour 24 (1 PM – 2 PM) — The Redemption of France

At 2 PM on June 11, 1978, Didier Pironi and Jean-Pierre Jaussaud cross the line in the Renault-Alpine A442 B #2, completing 5,030 km @ 209 km/h.

The circuit erupts. Mechanics cry, fans sing “La Marseillaise.”

For the first time since 1950, a French team, French engine, and French drivers have conquered Le Mans.

Pironi collapses beside the car, helmet still on, shaking with relief.

Jaussaud weeps. The turbo has become a triumph.

Renault finally does what Matra began — and in doing so, closes a generation.

Aftermath & Results

Winners: Didier Pironi / Jean-Pierre Jaussaud — Renault Alpine A442 B Turbo

Distance: 5,030 km @ 209 km/h

Second: Bob Wollek / Jacky Ickx / Jürgen Barth — Porsche 936 Turbo (+5 laps)

Third: Raymond Touroul / Christian Hubert — Porsche 935 Turbo (+18 laps)

Fastest Lap: Jean-Pierre Jabouille (Renault A442 B) — 3′34.2″ (~227 km/h)

Significance:

Renault’s first and only Le Mans victory, crowning a decade of turbo development.

First all-French triumph — car, drivers, engine, tyres, and fuel.

The A442 B’s canopy experiment proved both innovation and endurance could coexist.

Didier Pironi emerged as France’s next superstar, soon to rise to F1 glory.

The triumph completed the French arc begun by Matra — and marked the true arrival of the turbo era.

1978 was not just a victory.

It was absolution.

Sources

Automobile Club de l’Ouest (ACO) — Official 1978 24 Heures du Mans Results & Technical Report

Renault Sport / Gordini Archives — “A442 Programme de Victoire 1978”

Motorsport Magazine, July 1978 — “Renault’s Day of Deliverance”

Porsche Werk Weissach Archives — “936 vs A442 Performance Analysis 1978”

Goodwood Road & Racing — “1978: The French Dream Fulfilled”

1979 — Rain, Ruin, and the American Dream

Hour 0 (2:00 PM) — Storms Over the Sarthe

June 9, 1979.

Dark clouds roll over Le Mans. Thunder growls behind the grandstands as teams prepare for a race few expect to survive intact.

On the front rows:

Bob Wollek / Hurley Haywood / Manfred Schurti — Porsche 936/77 #14

Jacky Ickx / Brian Redman — Porsche 936/78 #12

Didier Pironi / Jean-Pierre Jaussaud — Renault Alpine A443 #1 (last year’s champions, now in long-tail configuration)

Klaus Ludwig / Don Whittington / Bill Whittington — Porsche 935 K3 #41 (Kremer Racing)

Dick Barbour / Rolf Stommelen / Paul Newman — Porsche 935 #70 (Dick Barbour Racing, USA)

The tricolor falls. The rain comes immediately. Le Mans 1979 begins under lightning and disbelief.

Hour 1 (3:00 PM) — Chaos in the Wet

Visibility drops to nothing. Cars aquaplane across Mulsanne, spinning like leaves.

Ickx takes control early, dancing the 936 through standing water with effortless precision. Behind him, the Renaults flounder, their massive power useless on a soaked track.

By 3 PM, half the prototypes have pitted for rain tyres — some twice.

The GT-class Porsches move forward, their rear-engined weight a gift in the storm.

Already, whispers ripple through the paddock: “A 935 could win this.”

Hours 2–3 (4–5 PM) — The French Collapse

The A443s, Renault’s final assault on Le Mans, begin to unravel.

Pironi’s car blows a turbo hose on lap 19. Jabouille’s sister car loses boost pressure soon after. Both limp to the pits under a torrent of rain.

Meanwhile, Ickx and Redman’s Porsche 936s trade the lead — their turbos whistling, their wipers barely keeping up.

In the chaos, two privateer Porsches — the Kremer K3 #41 and the Dick Barbour #70 — slip quietly into the top five.

The crowd, drenched and delirious, cheers every lap. The giants are stumbling, and the independents are rising.

Hours 4–8 (6 PM – Midnight) — The Night of the Privateers

By sunset, the track glistens with reflections of tail lights and headlights.

The 935 K3s thrive in the slippery dark, their raw traction and lower boost proving ideal.

At 8 PM, disaster: the factory 936 #14 retires with electrical failure.

At 10 PM, the sister car of Ickx / Redman begins losing oil pressure.

By midnight, Porsche’s factory effort is finished.

Le Mans belongs now to private hands.

At the front:

#41 Kremer Porsche 935 K3 — Ludwig / Whittington / Whittington

#70 Dick Barbour Porsche 935 — Stommelen / Newman / Barbour

The crowd can hardly believe it. A Hollywood actor is running second at Le Mans.

Hours 9–12 (Midnight – 3 AM) — Hollywood in the Rain

Paul Newman takes his first full stint at 12:20 AM. Rain still falls.

He drives cautiously, steadily — within seconds of Stommelen’s pace, never putting a wheel wrong.

Marshals salute him quietly as he passes.

At 2 AM, Newman brings the #70 Porsche in second overall, safe and strong.

Barbour’s crew, soaked and sleepless, hugs the American star before Stommelen takes over again.

The German veteran pushes hard — but not enough to catch Ludwig’s flying K3.

By 3 AM, the order stands: Kremer first, Barbour second, Rondeau third.

The factory teams are gone. The rain belongs to the dreamers.

Hours 13–16 (3 AM – 6 AM) — Survivors’ Dawn

Dawn breaks grey and cold. The track steams as the sun touches wet asphalt.

The K3 still leads, Ludwig flawless in the worst conditions imaginable.

Stommelen, pushing the #70 Barbour car, nearly spins twice but saves it each time. Newman watches from the pit wall, quiet, focused, utterly transformed from movie star to racer.

Renault’s pits are silent — both cars retired before sunrise.

Ickx, sitting in the Porsche garage, shrugs to journalists: “Le Mans chose new heroes this year.”

By 6 AM, the K3 leads by two laps over Newman’s 935.

Hours 17–20 (6 AM – 10 AM) — The Great Endurance Divide

The rain stops. Sunlight returns. Now the turbo cars can breathe again.

The K3 runs like a tank — crude but indestructible. The Dick Barbour car holds steady, clean, and consistent.

At 9 AM, Rolf Stommelen’s experience keeps the Americans in contention. He even takes fastest lap: 3′50.9″.

But Kremer’s car, with lightweight bodywork and better fuel economy, holds the advantage.

By 10 AM, the margin is three laps.

Hours 21–23 (10 AM – 1 PM) — When Legends Rest

The race settles into rhythm. The Whittington brothers — amateurs by F1 standards, professionals by will — share driving duties with deadly calm.

Every shift perfect, every pit stop clean.

In the Barbour garage, mechanics check every turbo line, every wheel nut. Newman looks on, exhausted, covered in grease.

He tells a reporter quietly:

“It’s not a movie. It’s something else entirely.”

At 12:30 PM, the #41 Kremer Porsche holds a four-lap cushion. The Barbour car runs smooth, refusing to fade.

Hour 24 (1 PM – 2 PM) — Private Glory

At 2 PM on June 10, 1979, Klaus Ludwig, Don Whittington, and Bill Whittington cross the line in the Kremer Racing Porsche 935 K3 #41, completing 4,986.6 km @ 207.6 km/h.

Behind them, just three laps down, Rolf Stommelen, Dick Barbour, and Paul Newman bring home the Porsche 935 #70, second overall and first in IMSA class.

The paddock explodes in cheers — not corporate, but human.

Two private teams, two miracles of survival, have conquered Le Mans.

Newman climbs atop the pit wall, waves to the crowd, and grins through exhaustion.

Hollywood has found its truth in oil, rain, and courage.

Aftermath & Results

Winners: Klaus Ludwig / Don Whittington / Bill Whittington — Porsche 935 K3 (Kremer Racing)

Distance: 4,986.6 km @ 207.6 km/h

Second: Rolf Stommelen / Dick Barbour / Paul Newman — Porsche 935 (Dick Barbour Racing) (+3 laps)

Third: Jean Rondeau / Jean Ragnotti / Bernard Darniche — Rondeau M379 Cosworth (+18 laps)

Fastest Lap: Rolf Stommelen (Porsche 935) — 3′50.9″ (~214 km/h)

Significance:

First and only overall Le Mans victory for a Group 5 car — the Porsche 935 K3, a modified 911.

A privateer 1–2 finish, unprecedented in modern Le Mans history.

Paul Newman’s second-place debut became one of motorsport’s great stories — proof that passion could cross from cinema to endurance.

Renault withdrew after the race to focus on Formula 1, leaving Porsche to dominate the next decade.

1979 remains the year Le Mans turned human again — where persistence, improvisation, and grit triumphed over factory might.

Sources

Automobile Club de l’Ouest (ACO) — Official 1979 24 Heures du Mans Results & Technical Report

Porsche Werk Weissach Archives — “935 K3 Performance Summary, Le Mans 1979”

Motorsport Magazine, July 1979 — “Rain, Ruin, and the Privateers”

Goodwood Road & Racing — “1979: When the Dreamers Won”

Dick Barbour Racing Team Records — “935 Le Mans Campaign, 1979”

1980 — The Man, the Machine, and the Miracle of Le Mans

Hour 0 (4:00 PM) — A French Dream Begins

June 14, 1980.

The sun blazes over the Sarthe as 50 cars line the grid. At the front: the gleaming Porsche 908/80s of Ickx & Joest, sleek and favored.

But in the middle of the pack sits something different — black, silver, and proudly French: the Rondeau M379B, designed, built, and driven by Jean Rondeau himself.

The privateer from Le Mans has no factory support, only courage and local sponsorship from Inaltera and Otis. His car, powered by a humble Ford Cosworth DFV, will run 24 hours against the world’s mightiest.

When the tricolor drops, the Porsche turbos leap ahead, leaving the Rondeau behind. No one yet imagines what this day will become.

Hour 1 (5:00 PM) — The Expected Order

Porsche controls the race instantly.

Jacky Ickx / Reinhold Joest in the 908/80 lead effortlessly, the flat-six turbo spooling cleanly out of Tertre Rouge.

Rondeau, sharing with Jean-Pierre Jaussaud — last year’s Renault winner — settles into 12th, driving like a man pacing destiny.

By 5 PM, Porsche’s advantage is measured in minutes. The French car runs flawlessly but modestly.

Hours 2–3 (6–7 PM) — Precision vs Passion

The 908/80s of Ickx and Joest are relentless.

Rondeau, sweating inside his hand-built cockpit, maintains 3′50″ laps — slower but steady. His mechanics, friends and neighbors from Le Mans, clap every time he passes the pits.

At 6:30 PM, the first major incident: the Kremer 935 crashes heavily at Maison Blanche. Safety cars slow the field.

Rondeau slips quietly into 7th.

By 7 PM, the sun softens and the dream begins to flicker.

Hours 4–8 (8 PM – Midnight) — The Storm and the Slipstream

Rain returns — Le Mans never grants easy nights.

Ickx continues imperiously, but water seeps into his Porsche’s electrics. Small misfires begin.

Rondeau, knowing every curve of this track since childhood, drives by instinct. The M379’s lighter DFV breathes better in wet air.

By 10 PM, Rondeau is 3rd.

At midnight, he passes a slowing Porsche 935 to take 2nd. The French crowd stirs, umbrellas rising, flags unfurling.

Hours 9–12 (Midnight – 3 AM) — The Fall of the Giant

At 1 AM, the leading Porsche 908/80 slows — gearbox failure. Ickx pits; mechanics swarm, replacing the entire rear assembly.

The stop costs 42 minutes.

When the white car returns, it’s 5th.

The black Rondeau #16 leads Le Mans.

Inside the cockpit, Jaussaud keeps the revs low, voice calm over radio:

“Elle est parfaite, Jean.”

She’s perfect, Jean.

At 3 AM, the rain stops. Rondeau leads by two laps.

Hours 13–16 (3 AM – 6 AM) — Endurance, Not Speed

Dawn reveals the track glistening. The Rondeau cruises at 3′55″ per lap, conserving its Cosworth engine.

Behind, Ickx attacks relentlessly, setting laps 15 seconds faster.

By 6 AM, the Porsche is back on the lead lap.

The duel is inevitable: the world’s best driver versus the world’s bravest.

Hours 17–20 (6 AM – 10 AM) — The Pressure Mounts

The morning sun rises on tension so sharp it hums.

Ickx cuts the gap with each stint. By 9 AM, the two leaders are separated by just one pit stop.

Rondeau climbs back in for his final double stint. His face is grey with fatigue; he has barely slept in two days.

He drives like a man in trance, using every inch of home advantage.

At 10 AM, the Rondeau and the Porsche flash past the pits side-by-side. The crowd erupts in national pride and disbelief.

Hours 21–23 (10 AM – 1 PM) — The Duel for the Soul of Le Mans

Ickx pushes. The Porsche screams down Mulsanne at 340 km/h, the Rondeau 30 slower but more stable.

At 11:30 AM, Ickx retakes the lead under braking at Arnage. The tricolor flags fall silent.

Then, at 12:05 PM, fate intervenes — the Porsche loses oil pressure. The 908 limps into the pits trailing smoke. Mechanics look on helplessly.

The crowd explodes — Rondeau is back in front.

Hour 24 (1 PM – 2 PM) — The Man and His Machine

At 2 PM on June 15, 1980, Jean Rondeau and Jean-Pierre Jaussaud cross the line in the Rondeau M379B #16, completing 4,648 km @ 194.0 km/h.

The grandstands erupt into tears and song. Rondeau stops the car on the front stretch, climbs out, and falls to his knees beside it.

He has done what no one else ever has — won Le Mans in a car bearing his own name.

Ickx finishes second, smiling, shaking Rondeau’s hand.

The Porsche legend bows to the local dreamer.

Aftermath & Results

Winners: Jean Rondeau / Jean-Pierre Jaussaud — Rondeau M379B Ford Cosworth

Distance: 4,648.2 km @ 194.0 km/h

Second: Jacky Ickx / Reinhold Joest — Porsche 908/80 Turbo (+2 laps)

Third: Hurley Haywood / Dick Barbour — Porsche 935 K3 (+10 laps)

Fastest Lap: Jacky Ickx (Porsche 908/80) — 3′34.2″ (~226 km/h)

Significance:

The only time in history a driver won Le Mans in a car he designed and built.

Rondeau’s victory symbolized the triumph of craftsmanship over corporations.

France’s second consecutive win with French-built machinery, cementing a new golden age of Gallic endurance.

The Cosworth DFV, born for Formula 1, achieved its final Le Mans glory.

The emotional high of 1980 made Jean Rondeau a national hero — a symbol of the soul of Le Mans itself.

Le Mans 1980 was not about horsepower or politics.

It was about heart.

Sources

Automobile Club de l’Ouest (ACO) — Official 1980 24 Heures du Mans Results & Technical Report

Rondeau Engineering Archives — “M379B Programme 1980 : L’Homme et la Machine”

Motorsport Magazine, July 1980 — “Rondeau’s Miracle at Le Mans”

Goodwood Road & Racing — “1980: The Year a Dreamer Beat the Giants”

Porsche Werk Weissach Archives — “908/80 Endurance Report 1979–80”

1981 — The Return of the Empire

Hour 0 (4:00 PM) — A Champion Defends His Home

June 13, 1981.

A light drizzle falls on the Circuit de la Sarthe. The French grandstands are still painted blue and silver from the year before.

In the pitlane stands Jean Rondeau, Le Mans’ hometown hero, back to defend the impossible: a man, his workshop, and his dream against Porsche’s global machine.

At the front of the grid:

Rondeau M379C #8 — Jean Rondeau / Jean-Louis Schlesser

Rondeau M379C #7 — Henri Pescarolo / Patrick Tambay

Porsche 936/81 #11 — Jacky Ickx / Derek Bell

Porsche 936/81 #12 — Jürgen Barth / Hurley Haywood

Rain spits on the tarmac as the tricolor falls.

Rondeau accelerates perfectly, his Cosworth engine screaming past the pits — a privateer leading giants once more.

Hour 1 (5:00 PM) — The Hunter Returns

Ickx wastes no time. Within ten laps, the silver Porsche #11 closes on Rondeau’s black car, the turbo hiss a reminder of what’s coming.

Rondeau defends like a streetfighter, darting through traffic, forcing Ickx to wait.

By 5 PM, the rain clears. Ickx strikes down the Mulsanne — 340 km/h, past the French dream in one unbroken sweep of power.

The crowd groans, but Rondeau stays close. He knows the 936’s strength comes at a cost: heat and fuel.

Hours 2–3 (6–7 PM) — The Duel of Pace and Pride

The early evening settles into a rhythm of attrition.

The two factory Porsches lead, running perfectly synchronized lap times in the 3′40″s.

Rondeau’s M379Cs, light and agile, match them through the corners but lose 10 seconds on the straights.

At 6:45 PM, Pescarolo pits with misfiring electrics — a 20-minute repair.

Rondeau stays out, driving with all the fury of a man who built the car with his own hands.

At 7 PM, Porsche leads. Rondeau fights from third.

Hours 4–8 (8 PM – Midnight) — Blue Shadows, Silver Ghosts

Night descends in still air. The Porsches glide through darkness, their headlights cutting perfect symmetry across the forest.

Rondeau’s cars, older and harder-driven, begin to suffer.

At 9 PM, the #7 M379C of Pescarolo retires with clutch failure. Tambay consoles his mechanics — “Elle a donné tout.”

Rondeau’s #8 car soldiers on, still third.

At midnight, the Porsches lap flawlessly, Ickx’s average speed over 210 km/h in the dark.

Le Mans, once again, begins to feel German.

Hours 9–12 (Midnight – 3 AM) — The Rise of the Machines

The night is Porsche’s.

Both 936/81s run like clockwork, their twin-turbo flat-sixes humming without strain. Rondeau’s Cosworth V8 howls bravely, but fatigue sets in.

At 1 AM, a minor fuel leak costs six laps.

Meanwhile, Ickx drives with godlike calm.

After four stints, he has spent over six hours in the car — setting fastest laps in near-total darkness.

By 3 AM, the lead is secure: Porsche 1–2, Rondeau 3rd, the rest fading.

Hours 13–16 (3 AM – 6 AM) — Dawn Over Defeat

Fog rolls over the circuit as dawn breaks pale and cool.

Rondeau’s mechanics, working with little sleep, patch leaks and tighten bolts. Their car keeps running, still roaring for pride.

At 5 AM, Ickx climbs in again.

He attacks with surgical rhythm, maintaining 3′39″ laps even as the sun rises into his visor.

By 6 AM, Porsche leads by eight laps.

Rondeau’s dream is intact but distant.

Hours 17–20 (6 AM – 10 AM) — The Endurance of Faith

The morning heat brings back memories of 1980. The French fans refuse to give up, waving “Courage Rondeau !” signs from every grandstand.

Rondeau himself takes another stint, his movements slow but steady.

The car runs perfectly — no speed, no chance, but all soul.

Behind him, Pescarolo, now watching from the pit wall, nods in respect: “Il ne renonce jamais.”

He never gives up.

By 10 AM, the Porsche #11 of Ickx and Bell is uncatchable — but the man from Le Mans will not surrender.

Hours 21–23 (10 AM – 1 PM) — The Reign of Efficiency

The afternoon grows hot and heavy.

The 936/81s continue their unbroken dominance. Porsche’s engineers, led by Norbert Singer, manage boost and temperature with metronomic control.

At 11 AM, Rondeau’s Ford engine misfires again; they nurse it home, changing plugs and praying.

The pit lane applauds when the car re-emerges — the last French hope still running strong.

At 1 PM, Ickx eases off the pace. The job is nearly done.

Hour 24 (1 PM – 2 PM) — The Last Lap of Legends

At 2 PM on June 14, 1981, Jacky Ickx and Derek Bell cross the line in the Porsche 936/81 #11, completing 4,986 km @ 207.6 km/h, sealing one of the most commanding wins in endurance history.

Ickx climbs from the cockpit, weary but triumphant — his sixth Le Mans victory, tying the all-time record.

Beside him, Derek Bell embraces him with quiet awe.

Moments later, the black Rondeau #8 crosses the line in second. The grandstands rise as one.

Jean Rondeau — the builder, the believer — finishes behind the greatest of all.

For a man racing out of his own workshop, second place feels like immortality.

Aftermath & Results

Winners: Jacky Ickx / Derek Bell — Porsche 936/81 Turbo

Distance: 4,986.3 km @ 207.6 km/h

Second: Jean Rondeau / Jean-Louis Schlesser — Rondeau M379C Cosworth (+14 laps)

Third: Hurley Haywood / Al Holbert / Vern Schuppan — Porsche 936/81 Turbo (+16 laps)

Fastest Lap: Jacky Ickx (Porsche 936/81) — 3′36.8″ (~226 km/h)

Significance:

Porsche’s return to dominance, their 7th overall win and the first since 1977.

Jacky Ickx’s sixth Le Mans victory, solidifying his status as the sport’s greatest endurance driver.

Rondeau’s valiant defense, proving his 1980 win was no fluke — only outgunned by Porsche’s full factory might.

The 936/81 became the perfect synthesis of power and efficiency, a last hurrah before the Group C era.

For France, it was a bittersweet year — a local hero humbled, yet never defeated.

Le Mans 1981 was a changing of the guard —

a salute between dreamers and dynasties.

Sources

Automobile Club de l’Ouest (ACO) — Official 1981 24 Heures du Mans Results & Technical Report

Porsche Werk Weissach Archives — “Project 936/81: Race Analysis and Turbo Strategy”

Rondeau Racing Archives — “M379C Programme 1981: Défense du Titre”

Motorsport Magazine, July 1981 — “Ickx and Bell: Masters of Le Mans”

Goodwood Road & Racing — “1981: The Return of the Empire”