Le Mans 1982 - 1993

Group C Efficiency Era

1982 — The Birth of Group C

Hour 0 (4:00 PM) — The Future Arrives in Silver

June 19, 1982.

A thunderstorm rumbles over Le Mans, but the pit lane glows with something electric — not rain, but possibility.

This is the first year of the new Group C regulations: prototypes built not merely for speed, but for efficiency. Fuel consumption is limited. Aerodynamics are weaponized.

At the front:

Porsche 956 #1 — Jacky Ickx / Derek Bell

Porsche 956 #2 — Jochen Mass / Vern Schuppan

Porsche 936C #3 — Hurley Haywood / Al Holbert

Rondeau M382 #8 — Jean Rondeau / Henri Pescarolo

WM P82 Peugeot — early turbo French prototype

Lancia LC1s, Ford C100, and a field of daring experiments.

The tricolor drops. The twin-turbo Porsches surge forward with uncanny stability — ground-effect downforce sucking them to the tarmac as the rain begins to fall.

Group C has arrived, and it looks like the future.

Hour 1 (5:00 PM) — Learning the Language of Fuel

The new rules allow only 600 litres of fuel per 1,000 km.

That means patience — something few Le Mans drivers possess.

Ickx paces perfectly: 3′36″ laps, short-shifting out of Tertre Rouge, boost limited to 1.2 bar.

Behind him, the privateer Porsches go too hard, too soon. Rondeau keeps close, his M382 still DFV-powered and lighter in the corners.

By 5 PM, Porsche #1 leads from #2. Rondeau sits 3rd, watching the silver cars glide like ghosts through the mist.

Hours 2–3 (6–7 PM) — When the Rain Falls Sideways

The skies open.

On the straights, water shears off the 956’s tail like vapor. Ickx doesn’t lift — his car’s new underfloor tunnels glue it to the circuit.

By 7 PM, the French cars begin to slide helplessly.

Two Rondeaus spin at Indianapolis. The WM Peugeot aquaplanes off at Maison Blanche.

The 956s — unfazed, unflinching — extend their lead to three laps.

In the garages, engineers whisper: “This is a new kind of racing.”

Hours 4–8 (8 PM – Midnight) — Precision in the Dark

Night descends with strange beauty. The silver Porsches glow under floodlights, their tail lights burning through the fog.

Bell takes over from Ickx, maintaining 3′44″ laps — perfectly inside the fuel target.

Mass and Schuppan run second, while the third 936 (Holbert / Haywood) keeps Porsche’s sweep alive.

By midnight, the rest of the field is battered and broken. Only two cars remain within 10 laps of the lead.

The new 956 is not just fast — it is untouchable.

Hours 9–12 (Midnight – 3 AM) — The Dawn of the Machine Age

The 956’s telemetry glows softly in the cockpit — a first at Le Mans. Fuel data, boost pressure, oil temp: every number matters.

The human element fades into the hum of computers and control.

At 2 AM, Rondeau’s last car retires with engine failure. The French dream dies quietly in the rain.

Porsche’s trio continues without fault.

At 3 AM, #1 Ickx / Bell lead #2 Mass / Schuppan by four laps.

Hours 13–16 (3 AM – 6 AM) — Ickx and the Immaculate Rhythm

Ickx returns for the dawn shift. He drives with supernatural calm — each lap a near-identical 3′37″, throttle smooth as breath.

The 956 sings through the fog, twin turbos whistling in unison.

By sunrise, the Porsches hold a 1–2–3 formation.

Norbert Singer, their creator, watches from the pit wall. His face barely moves, but his eyes say everything: the experiment works.

Hours 17–20 (6 AM – 10 AM) — The Science of Endurance

As the sun climbs, Bell manages the delicate balance of fuel and speed. Every tenth counts — not to win, but to stay within regulations.

The telemetry says they can push harder. Bell obliges.

At 8 AM, he sets the race’s fastest lap: 3′33.9″ — nearly qualifying pace, 225 km/h average.

Behind, Mass keeps station, ensuring a formation finish.

The rest of the field fades to distant background noise.

Hours 21–23 (10 AM – 1 PM) — The Era Turns

By midday, Porsche has lapped the field. Not once — but twice.

Only mechanical failure could stop them now.

For the first time in Le Mans history, a single constructor occupies the entire podium.

Bell and Ickx trade quiet smiles in the pits — veterans turned pioneers.

Rondeau’s mechanics watch respectfully. The local hero’s reign is over, but his spirit lingers in the air.

Hour 24 (1 PM – 2 PM) — The Perfect Race

At 2 PM on June 20, 1982, Jacky Ickx and Derek Bell cross the line in the Porsche 956 #1, completing 4,991.18 km @ 207.3 km/h.

It is Porsche’s eighth overall victory, but this one feels different — colder, cleaner, inevitable.

For Ickx, it’s his sixth win — the same number as the race itself has decades of myth.

For Bell, it marks the beginning of a dynasty that will span the rest of the decade.

When the chequered flag falls, Bell removes his gloves, looks up at the grandstands, and says quietly:

“It feels like we’ve built the future.”

Aftermath & Results

Winners: Jacky Ickx / Derek Bell — Porsche 956 Turbo (Group C)

Distance: 4,991.18 km @ 207.3 km/h

Second: Jochen Mass / Vern Schuppan — Porsche 956 (+3 laps)

Third: Hurley Haywood / Al Holbert / Jürgen Barth — Porsche 936C (+8 laps)

Fastest Lap: Derek Bell (Porsche 956) — 3′33.9″ (~225 km/h)

Significance:

Debut victory for the Porsche 956, launching a decade of Group C dominance.

First Le Mans podium sweep by a single manufacturer.

First car with ground effects and telemetry to win Le Mans.

Jacky Ickx’s record-tying sixth victory, and the start of Bell’s endurance legacy.

The race marked the end of the romantic privateer era and the birth of a scientific one.

Le Mans 1982 was not a battle — it was a proof of concept.

The future of endurance racing had arrived in silver.

Sources

Automobile Club de l’Ouest (ACO) — Official 1982 24 Heures du Mans Results & Technical Bulletin

Porsche Werk Weissach Archives — “Project 956: Group C Fuel Data & Ground Effect Development”

Motorsport Magazine, July 1982 — “The Birth of Group C”

Goodwood Road & Racing — “1982: Porsche 956 and the New Age of Endurance”

Shell / Dunlop Technical Report — “Fuel Efficiency and Tire Performance in Group C Prototypes (1982)”

Would you like to continue with 1983 next — the brutal sequel, when Porsche faced its own might as privateers joined the war, and Derek Bell and Vern Schuppan fought through fire, failure, and destiny in the longest 24 hours of their lives?

1983 — The Battle of the Silver Armies

Hour 0 (4:00 PM) — A War Among Brothers

June 18, 1983.

Le Mans bakes beneath a rare summer sun. The paddock glitters silver, blue, and white — all wearing Porsche badges.

The lineup:

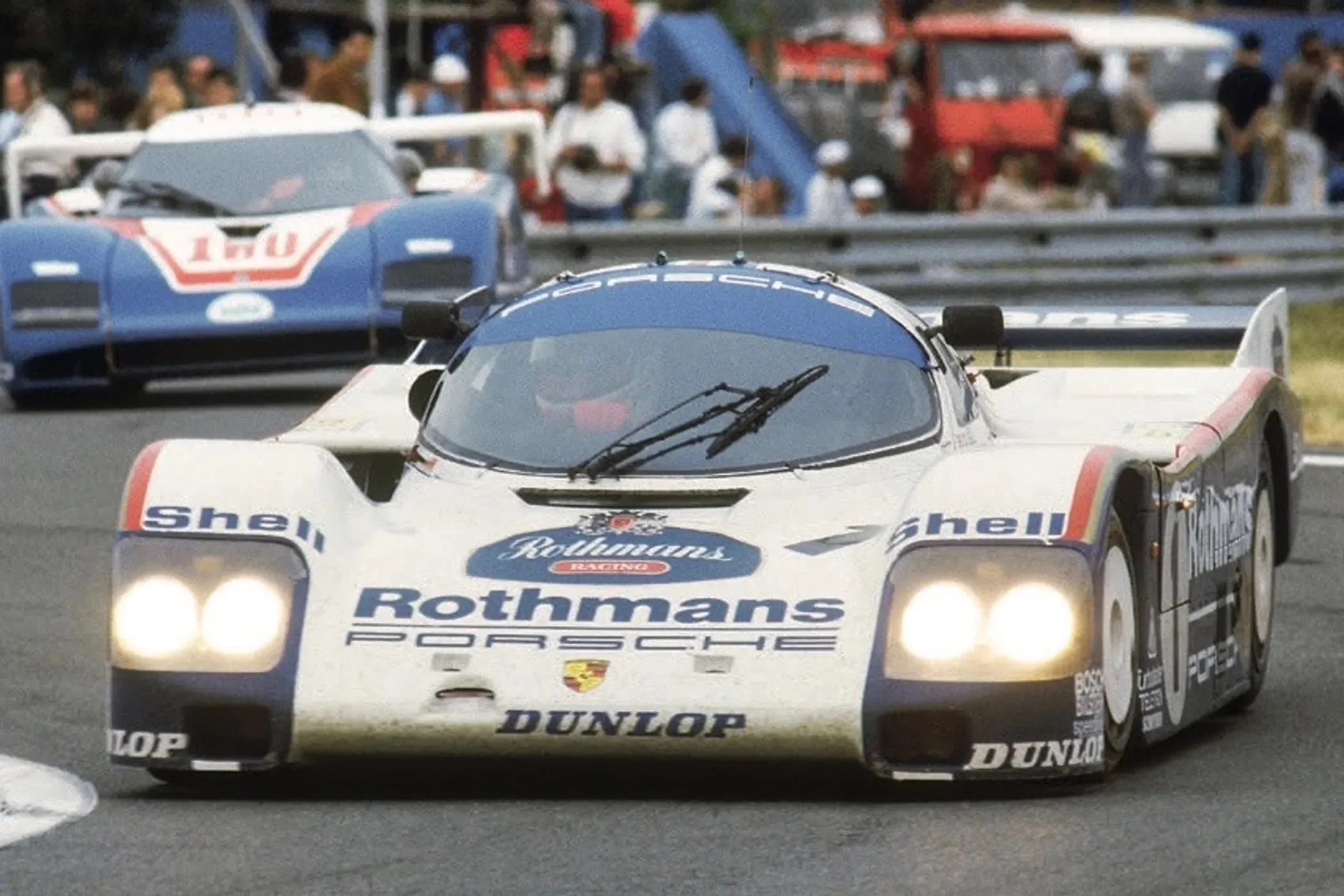

#3 Porsche 956 Rothmans — Vern Schuppan / Al Holbert / Hurley Haywood

#1 Porsche 956 Rothmans — Jacky Ickx / Derek Bell

#21 Porsche 956 Privateer (Joest Racing) — Bob Wollek / Klaus Ludwig

#14 Porsche 956 Privateer (Kremer) — Mario Andretti / Michael Andretti / Philippe Alliot

#7 Lancia LC2 — Riccardo Patrese / Michele Alboreto

In Group C’s second year, Porsche’s dominance is total — eleven 956s fill the grid. Even Lancia’s scarlet LC2s, running Ferrari-built V8 turbos, look like intruders.

The tricolor falls. Ickx launches ahead, Bell waving him through. Behind, Lancia’s scream fades to static. The 956s fan out in formation — the race is theirs to lose.

Hour 1 (5:00 PM) — The Opening Salvo

The works cars trade fastest laps, 3′31″ to 3′33″. The Rothmans livery gleams like polished armor in the sun.

Ickx’s #1 leads; Schuppan’s #3 stays close.

Behind them, Joest’s #21 car — lighter, freer of factory restrictions — lurks ominously.

The battle isn’t Porsche vs Lancia. It’s Porsche vs Porsche.

By 5 PM, the top five are all 956s.

Hours 2–3 (6–7 PM) — The Tactical Race

Bell radios fuel numbers; the engineers calculate efficiency down to the litre.

The factory cars must obey Porsche’s fuel limit — 600 L/1000 km — but Joest’s privateer entry runs a more aggressive map.

That freedom lets #21 pull alongside down Mulsanne.

By 7 PM, Ludwig’s Joest 956 leads Le Mans. The factory team looks uneasy.

Hours 4–8 (8 PM – Midnight) — The Night of Endurance

As darkness falls, strategy replaces speed.

Lancia’s LC2s, brutal but fragile, break first — Patrese retires with gearbox failure by 9 PM, Alboreto by 11.

The race narrows to six Porsches.

Ickx and Bell run like metronomes, but Joest’s car continues longer between refuels — an audacious gamble.

At midnight, Ludwig leads by two laps. Ickx stalks him through the rain, headlights slicing through spray.

The hunter has become the hunted.

Hours 9–12 (Midnight – 3 AM) — Rain and Reckoning

The storm intensifies. Visibility drops to ten metres. The 956s, their ground-effect tunnels sucking in water, become nervous and twitchy.

At 1 AM, disaster: the leading Joest 956 spins at Arnage. Ludwig saves it but loses precious time.

Moments later, Ickx retakes the lead — calm, surgical, relentless.

By 3 AM, the Rothmans Porsches run 1-2 again, but the Joest car lurks a minute behind, shadowing their every move.

Hours 13–16 (3 AM – 6 AM) — The Dawn of Doubt

Dawn glows faint pink over a soaked circuit. The Rothmans pit is all routine and discipline.

Then — a tremor. Bell’s #1 956 refuses to restart after a refuel. The starter motor jams. Mechanics fight for six minutes.

When it fires, #3 (Holbert/Schuppan/Haywood) inherits the lead.

For the first time, Ickx is chasing instead of commanding.

By 6 AM, three 956s remain on the lead lap: #3, #1, and #21.

Hours 17–20 (6 AM – 10 AM) — The War of Attrition

The sun returns, and with it, heat. Gearboxes begin to fail across the field.

Joest’s #21 loses third gear. Rondeau’s private M382 retires with oil loss.

At 8 AM, Bell climbs in for a triple stint, chasing the sister #3 car with everything he has left.

Lap after lap, the gap holds steady at one minute.

Holbert, calm and calculating, refuses to over-rev.

At 10 AM, Porsche #3 leads #1 by 56 seconds.

Hours 21–23 (10 AM – 1 PM) — Ickx’s Final Charge

The track dries completely. The 956s reach full speed again — 350 km/h down Mulsanne.

Ickx senses opportunity. His rhythm sharpens, his corner entries cleaner.

By noon, he has cut the gap to 20 seconds.

Then, fate intervenes: the #1 car’s turbocharger begins to smoke. Power drops.

Ickx keeps going, but the numbers fall: 3′31″… 3′36″… 3′40″.

Bell radios, “It’s over, Jacky.”

Hour 24 (1 PM – 2 PM) — The Triumph of Discipline

At 2 PM on June 19, 1983, Vern Schuppan, Al Holbert, and Hurley Haywood cross the line in the Porsche 956 #3, completing 5,087 km @ 212 km/h — the first car in Le Mans history to average over 130 mph.

Holbert raises a fist through the cockpit roof vent. Behind him, the #1 car limps home second, Ickx and Bell dignified in defeat.

Joest’s #21 finishes third, proving that independence can still bite the factory hand.

In the Rothmans garage, Norbert Singer writes two words in his notebook: “Perfect machine.”

Aftermath & Results

Winners: Vern Schuppan / Al Holbert / Hurley Haywood — Porsche 956 Rothmans Works Team

Distance: 5,087.3 km @ 212.0 km/h

Second: Jacky Ickx / Derek Bell — Porsche 956 Rothmans (+1 lap)

Third: Klaus Ludwig / Bob Wollek / Stefan Johansson — Porsche 956 Joest Racing (+6 laps)

Fastest Lap: Jacky Ickx (Porsche 956) — 3′28.9″ (~228 km/h)

Significance:

First Le Mans race to exceed 5,000 km — a record of consistency and precision.

Porsche’s ninth overall win, solidifying Group C domination.

Three different Porsche teams on the podium, proving the 956’s universality.

Jacky Ickx’s final factory Le Mans appearance, ending an era of poetic mastery.

A race that confirmed: endurance had become engineering.

Le Mans 1983 was not chaos — it was choreography.

Every lap a calculation, every victory a formula, every driver a cog in a beautiful machine.

Sources

Automobile Club de l’Ouest (ACO) — Official 1983 24 Heures du Mans Results & Fuel Data Report

Porsche Werk Weissach Archives — “956 Group C Program Year 2: Telemetry and Race Strategy”

Motorsport Magazine, July 1983 — “The Battle of the Silver Armies”

Goodwood Road & Racing — “1983: Porsche vs Porsche — A War Among Brothers”

Rothmans Porsche System Engineering — “Le Mans 1983 Race Post-Analysis”

1984 — The Privateer That Beat the Factory

Hour 0 (4:00 PM) — Ghosts in the Mist

June 16, 1984.

The Circuit de la Sarthe hums beneath low clouds. The reigning champions, Porsche, return not with hunger but with certainty.

Their silver-and-blue Rothmans 956s stand poised, while in the next garage, a quiet yellow-and-white car sits almost forgotten — Joest Racing Porsche 956 #7, chassis 117, an ex-works machine two seasons old.

Its drivers:

Klaus Ludwig (Germany)

Henri Pescarolo (France)

“Super Sub” Mauro Baldi (Italy, reserve)

They are not factory men. They are underdogs with a single spare gearbox and belief.

As the tricolor falls, the factory 956s rocket away in perfect formation.

The Joest car lags slightly — cautious, calm, saving its breath.

Le Mans 1984 begins not as a sprint, but as a slow act of rebellion.

Hour 1 (5:00 PM) — The Split of Intent

At the front, Ickx & Bell in the Rothmans #1 run qualifying pace from the start — 3′28″ laps, fuel burn be damned.

Behind, Joest’s Ludwig keeps his boost low, hovering in eighth, averaging 3′42″.

Rain threatens. Factory engineers smile: they expect a clean 1-2-3 sweep.

Ludwig simply mutters: “They’ll burn their wings before nightfall.”

Hours 2–3 (6–7 PM) — Aggression vs Endurance

The first drops fall.

The works 956s stay out too long on slicks; both Rothmans cars aquaplane through Arnage, narrowly avoiding disaster.

Joest’s 956 pits early for intermediates — a small call that changes everything.

By 7 PM, the privateer car is running third. The factory cars regain their rhythm, but the tone has changed: Ludwig’s patience is paying dividends.

Hours 4–8 (8 PM – Midnight) — Darkness and Discipline

Night closes in with mist.

Ickx leads. Bell follows.

But Ludwig’s #7 Joest Porsche runs perfectly, its fuel use microscopic. The engineers note 8 percent better economy than the factory average — enough to skip one stop every six hours.

Pescarolo, taking the second stint, drives with veteran precision. His silver hair glints in the cockpit light, a symbol of quiet defiance.

At midnight, #7 sits second overall.

Hours 9–12 (Midnight – 3 AM) — The Fall of the Factory

At 12:45 AM, drama: Ickx’s #1 956 slows on Mulsanne with fuel-pump failure. The sister #2 car pits with gearbox vibration soon after.

The factory line cracks.

Ludwig keeps circulating. Lap after lap after lap — steady, silent, precise.

At 2 AM, the yellow #7 Joest Porsche takes the lead.

A two-year-old car, two private mechanics, and a whisper of hope now lead Le Mans.

Hours 13–16 (3 AM – 6 AM) — The Coldest Hours

The night deepens into fog. Ludwig and Pescarolo alternate double stints. The Rothmans cars, repaired, chase from afar.

At 5 AM, Ickx sets a 3′29″ fastest lap — pure aggression. But even he can’t bridge the gap; Joest’s lighter fuel map gives them a one-lap edge per cycle.

As dawn burns orange through the mist, the privateer 956 still leads by three laps.

Hours 17–20 (6 AM – 10 AM) — The Factory Strikes Back

Morning brings clarity — and tension.

Porsche orders Bell and Ickx to push flat-out. They close the gap: three laps become two, then one.

At 9:30 AM, Ludwig responds with brutal consistency — six consecutive 3′33″ laps.

By 10 AM, the gap stabilizes again at 90 seconds.

In the Joest pit, Reinhold Joest lights a cigarette, exhales, and says to his crew: “If it stays dry, we win.”

Hours 21–23 (10 AM – 1 PM) — Endurance Turns to Faith

The final hours are pure tension.

Every vibration feels fatal, every sound a threat.

Pescarolo drives the penultimate stint, his 17th Le Mans, eyes hollow but steady.

At 12:15 PM, Ickx’s #1 Rothmans car retires — turbo failure.

The sister #2 car slows with gearbox issues.

Only one 956 runs flawlessly — the Joest car.

Hour 24 (1 PM – 2 PM) — David Beats Goliath

At 2 PM on June 17, 1984, Klaus Ludwig and Henri Pescarolo cross the line in the Joest Racing Porsche 956 #7, completing 5,005.04 km @ 208.5 km/h.

They have beaten Porsche with Porsche — using discipline, not power.

Ludwig collapses against the car, drenched in sweat and disbelief.

Pescarolo smiles faintly: “We built nothing new — we just refused to fail.”

In the Rothmans garage, Norbert Singer applauds quietly.

Porsche has lost — but to itself.

Aftermath & Results

Winners: Klaus Ludwig / Henri Pescarolo — Porsche 956 Joest Racing

Distance: 5,005.04 km @ 208.5 km/h

Second: Jacky Ickx / Derek Bell — Porsche 956 Rothmans (+2 laps)

Third: David Hobbs / Philippe Streiff / John Fitzpatrick — Porsche 956 John Fitzpatrick Racing (+6 laps)

Fastest Lap: Jacky Ickx (Porsche 956) — 3′28.9″ (~229 km/h)

Significance:

First overall win for a true privateer team in the Group C era.

Joest Racing’s first of many Le Mans victories, establishing its reputation as the master of endurance.

Henri Pescarolo’s fourth Le Mans win, tying him among the legends.

Porsche’s tenth overall victory, though not by its own hand — a poetic contradiction.

Proof that endurance had matured: the best strategy now beat the best funding.

Le Mans 1984 was not just a race — it was a quiet rebellion.

A reminder that brilliance doesn’t always wear factory colors.

Sources

Automobile Club de l’Ouest (ACO) — Official 1984 24 Heures du Mans Results & Fuel Consumption Records

Joest Racing Archives — “Le Mans 1984: Strategy and Fuel Maps”

Porsche Werk Weissach Technical Report — “Rothmans 956 vs Privateer Entries 1984”

Motorsport Magazine, July 1984 — “David Beats Goliath at Le Mans”

Goodwood Road & Racing — “1984: The Privateer That Beat Porsche”

1984 — The Privateer That Beat the Factory

Hour 0 (4:00 PM) — Ghosts in the Mist

June 16, 1984.

The Circuit de la Sarthe hums beneath low clouds. The reigning champions, Porsche, return not with hunger but with certainty.

Their silver-and-blue Rothmans 956s stand poised, while in the next garage, a quiet yellow-and-white car sits almost forgotten — Joest Racing Porsche 956 #7, chassis 117, an ex-works machine two seasons old.

Its drivers:

Klaus Ludwig (Germany)

Henri Pescarolo (France)

“Super Sub” Mauro Baldi (Italy, reserve)

They are not factory men. They are underdogs with a single spare gearbox and belief.

As the tricolor falls, the factory 956s rocket away in perfect formation.

The Joest car lags slightly — cautious, calm, saving its breath.

Le Mans 1984 begins not as a sprint, but as a slow act of rebellion.

Hour 1 (5:00 PM) — The Split of Intent

At the front, Ickx & Bell in the Rothmans #1 run qualifying pace from the start — 3′28″ laps, fuel burn be damned.

Behind, Joest’s Ludwig keeps his boost low, hovering in eighth, averaging 3′42″.

Rain threatens. Factory engineers smile: they expect a clean 1-2-3 sweep.

Ludwig simply mutters: “They’ll burn their wings before nightfall.”

Hours 2–3 (6–7 PM) — Aggression vs Endurance

The first drops fall.

The works 956s stay out too long on slicks; both Rothmans cars aquaplane through Arnage, narrowly avoiding disaster.

Joest’s 956 pits early for intermediates — a small call that changes everything.

By 7 PM, the privateer car is running third. The factory cars regain their rhythm, but the tone has changed: Ludwig’s patience is paying dividends.

Hours 4–8 (8 PM – Midnight) — Darkness and Discipline

Night closes in with mist.

Ickx leads. Bell follows.

But Ludwig’s #7 Joest Porsche runs perfectly, its fuel use microscopic. The engineers note 8 percent better economy than the factory average — enough to skip one stop every six hours.

Pescarolo, taking the second stint, drives with veteran precision. His silver hair glints in the cockpit light, a symbol of quiet defiance.

At midnight, #7 sits second overall.

Hours 9–12 (Midnight – 3 AM) — The Fall of the Factory

At 12:45 AM, drama: Ickx’s #1 956 slows on Mulsanne with fuel-pump failure. The sister #2 car pits with gearbox vibration soon after.

The factory line cracks.

Ludwig keeps circulating. Lap after lap after lap — steady, silent, precise.

At 2 AM, the yellow #7 Joest Porsche takes the lead.

A two-year-old car, two private mechanics, and a whisper of hope now lead Le Mans.

Hours 13–16 (3 AM – 6 AM) — The Coldest Hours

The night deepens into fog. Ludwig and Pescarolo alternate double stints. The Rothmans cars, repaired, chase from afar.

At 5 AM, Ickx sets a 3′29″ fastest lap — pure aggression. But even he can’t bridge the gap; Joest’s lighter fuel map gives them a one-lap edge per cycle.

As dawn burns orange through the mist, the privateer 956 still leads by three laps.

Hours 17–20 (6 AM – 10 AM) — The Factory Strikes Back

Morning brings clarity — and tension.

Porsche orders Bell and Ickx to push flat-out. They close the gap: three laps become two, then one.

At 9:30 AM, Ludwig responds with brutal consistency — six consecutive 3′33″ laps.

By 10 AM, the gap stabilizes again at 90 seconds.

In the Joest pit, Reinhold Joest lights a cigarette, exhales, and says to his crew: “If it stays dry, we win.”

Hours 21–23 (10 AM – 1 PM) — Endurance Turns to Faith

The final hours are pure tension.

Every vibration feels fatal, every sound a threat.

Pescarolo drives the penultimate stint, his 17th Le Mans, eyes hollow but steady.

At 12:15 PM, Ickx’s #1 Rothmans car retires — turbo failure.

The sister #2 car slows with gearbox issues.

Only one 956 runs flawlessly — the Joest car.

Hour 24 (1 PM – 2 PM) — David Beats Goliath

At 2 PM on June 17, 1984, Klaus Ludwig and Henri Pescarolo cross the line in the Joest Racing Porsche 956 #7, completing 5,005.04 km @ 208.5 km/h.

They have beaten Porsche with Porsche — using discipline, not power.

Ludwig collapses against the car, drenched in sweat and disbelief.

Pescarolo smiles faintly: “We built nothing new — we just refused to fail.”

In the Rothmans garage, Norbert Singer applauds quietly.

Porsche has lost — but to itself.

Aftermath & Results

Winners: Klaus Ludwig / Henri Pescarolo — Porsche 956 Joest Racing

Distance: 5,005.04 km @ 208.5 km/h

Second: Jacky Ickx / Derek Bell — Porsche 956 Rothmans (+2 laps)

Third: David Hobbs / Philippe Streiff / John Fitzpatrick — Porsche 956 John Fitzpatrick Racing (+6 laps)

Fastest Lap: Jacky Ickx (Porsche 956) — 3′28.9″ (~229 km/h)

Significance:

First overall win for a true privateer team in the Group C era.

Joest Racing’s first of many Le Mans victories, establishing its reputation as the master of endurance.

Henri Pescarolo’s fourth Le Mans win, tying him among the legends.

Porsche’s tenth overall victory, though not by its own hand — a poetic contradiction.

Proof that endurance had matured: the best strategy now beat the best funding.

Le Mans 1984 was not just a race — it was a quiet rebellion.

A reminder that brilliance doesn’t always wear factory colors.

Sources

Automobile Club de l’Ouest (ACO) — Official 1984 24 Heures du Mans Results & Fuel Consumption Records

Joest Racing Archives — “Le Mans 1984: Strategy and Fuel Maps”

Porsche Werk Weissach Technical Report — “Rothmans 956 vs Privateer Entries 1984”

Motorsport Magazine, July 1984 — “David Beats Goliath at Le Mans”

Goodwood Road & Racing — “1984: The Privateer That Beat Porsche”

1985 — The Twice-Born 956

Hour 0 (4:00 PM) — The Return of Chassis 117

June 15, 1985.

The summer sun burns high over Le Mans.

In the pitlane stands a familiar yellow-and-white car — Joest Racing’s Porsche 956 #7, chassis number 117, the same machine that conquered the 1984 race.

It is two seasons old, rebuilt in a small shop in Wald-Michelbach. The mechanics call it “The Old Lady.”

The odds are impossible:

The factory Porsche 956Bs return stronger than ever, now in Rothmans blue and white.

Lancia LC2s boast brutal Ferrari turbo V8s and new aerodynamic updates.

Richard Lloyd Racing, Brun, and John Fitzpatrick bring private 956s of their own.

Joest’s driver lineup:

Klaus Ludwig — the calculating German tactician.

Paolo Barilla — the young Italian endurance novice.

John Winter — the pseudonym of Dr. Louis Krages, a Bremen businessman racing under secrecy.

As the tricolor falls, the works Porsches leap forward, their twin turbos shrieking under perfect launch.

Ludwig’s Joest 956 settles calmly into eighth — where victory always begins.

Hour 1 (5:00 PM) — The Calm Before the Climb

The first hour sets the pattern: the works 956s of Ickx/Bell and Schuppan/Holbert sprint clear, the Lancias follow, and Joest plays the long game.

Fuel is the currency of Group C. Ludwig drives with a surgeon’s touch — short-shifting to 8,000 rpm, coasting into Mulsanne corner.

At 5 PM, telemetry shows Joest’s 956 is burning 8% less fuel per lap than the works cars.

By endurance standards, that’s prophecy.

Hours 2–3 (6–7 PM) — The Italian Storm

The Lancia LC2s of Patrese and Nannini charge hard, their Ferrari engines howling at 9000 rpm. They seize second place by raw pace, but their consumption is ruinous.

At 6:45 PM, one LC2 pits early — overheated and half-empty on fuel.

Ludwig keeps to plan: 3′39″ average, no drama.

By 7 PM, “The Old Lady” climbs quietly to fourth.

Hours 4–8 (8 PM – Midnight) — Night, the Great Equalizer

As dusk settles, the works Porsches dominate the timing screens — Ickx and Bell running metronomic laps, Schuppan close behind.

Joest Racing continues its quiet miracle: 25 laps per stint instead of 23.

By 10 PM, the Lancias begin to fall apart under relentless boost.

At 11:40 PM, Patrese’s LC2 catches fire in the pits — a flash of yellow flame and extinguishers.

At midnight, Ludwig hands to Winter. The businessman-turned-racer drives clean and conservative.

Position: third overall.

Gap to the lead: 4 laps.

Hours 9–12 (Midnight – 3 AM) — The Fall of the Factory

Le Mans, as always, demands a sacrifice.

At 1:12 AM, the Rothmans Porsche #1 (Ickx/Bell) loses oil pressure — retirement.

At 2:00 AM, the sister #2 car of Holbert/Schuppan pits with gearbox trouble; it never recovers full pace.

By 3 AM, Joest’s privateer 956 leads Le Mans.

In the garage, Reinhold Joest doesn’t celebrate. He simply checks his stopwatch, looks at Ludwig, and says, “Again, we keep it slow.”

Hours 13–16 (3 AM – 6 AM) — The Old Lady Runs Alone

Dawn creeps over a bruised sky.

The yellow Joest Porsche glows with streaks of oil and dirt, but runs flawlessly.

Barilla takes his first dawn stint — smooth, cautious, reverent. The car feels heavy, but faithful.

Behind them, Fitzpatrick’s 956 trails three laps back; Lancia’s last survivor is 15 laps adrift.

By 6 AM, Joest still leads.

In two years, chassis 117 has run nearly 10,000 racing kilometers at Le Mans — and still sings like steel.

Hours 17–20 (6 AM – 10 AM) — The Phantom Pursuit

The works Porsche engineers, red-eyed and sleepless, encourage the privateers behind Joest to push.

Brun’s 956 charges, Fitzpatrick’s car closes the gap to 90 seconds.

At 9 AM, Ludwig climbs back in and sets a sequence of 3′35″ laps — faster than qualifying.

The gap grows again.

At 10 AM, Joest’s lead returns to two full laps.

Hours 21–23 (10 AM – 1 PM) — Fuel, Faith, and Fatigue

The final morning tests endurance more than bravery.

Every bolt on the Joest car has been stretched by fatigue; the suspension creaks through Porsche Curves.

At 11 AM, the Fitzpatrick Porsche retires with a seized gearbox — the last serious threat gone.

Reinhold Joest radios: “Klaus, no heroics. Just bring her home.”

Ludwig responds: “I will. She deserves it.”

Hour 24 (1 PM – 2 PM) — The Immortal Car

At 2 PM on June 16, 1985, Klaus Ludwig, Paolo Barilla, and John Winter cross the line in the Joest Racing Porsche 956 #7, completing 4,970.98 km @ 207.0 km/h.

The grandstands erupt — not for glamour, but for grit.

A privateer has done what no factory ever has: won Le Mans twice with the same car.

Ludwig parks on the front straight, pats the roof, and whispers to the engine cover:

“Danke, alte Dame.” — Thank you, old lady.

Aftermath & Results

Winners: Klaus Ludwig / Paolo Barilla / John Winter — Porsche 956 (Joest Racing, Chassis 117)

Distance: 4,970.98 km @ 207.0 km/h

Second: David Hobbs / Philippe Streiff / Sarel van der Merwe — Porsche 956 John Fitzpatrick Racing (+3 laps)

Third: Jean Rondeau / John Paul Jr. / Preston Henn — Rondeau M382C Ford Cosworth (+12 laps)

Fastest Lap: Klaus Ludwig (Porsche 956 Joest) — 3′33.9″ (~225 km/h)

Significance:

Joest Racing’s second consecutive Le Mans victory — both with the same car, chassis 117.

Only car in Le Mans history to win the 24 Hours twice in a row.

First and only victory for a car without factory support against factory Porsches.

Klaus Ludwig’s second overall win, beginning a career that would span Group C glory and DTM titles.

The end of the “old guard” 956 before the arrival of Porsche’s new 962C.

Le Mans 1985 was not about innovation — it was about endurance made eternal.

A single car, born from genius and maintained by will, proving that machinery, like men, can possess souls.

Sources

Automobile Club de l’Ouest (ACO) — Official 1985 24 Heures du Mans Results & Race Analysis

Joest Racing Archives — “Chassis 117: Le Mans 1984–1985 Operational Notes”

Porsche Werk Weissach Technical Report — “956B vs 962C Development Comparison, 1985 Season”

Motorsport Magazine, July 1985 — “The Old Lady Wins Again”

Goodwood Road & Racing — “1985: The Twice-Born 956”

1986 — Victory in the Shadow of Fire

Hour 0 (4:00 PM) — The Return of the Empire

June 14, 1986.

A pale sun breaks through a grey sky as 50 cars line the Circuit de la Sarthe. Porsche dominates the grid — a fleet of 962Cs, successors to the legendary 956.

The Rothmans works entries are pure perfection: long-tailed, wind-swept, and menacing in blue and white.

Front row:

#1 Porsche 962C — Derek Bell / Hans-Joachim Stuck / Al Holbert

#2 Porsche 962C — Jochen Mass / Bob Wollek / Vern Schuppan

#17 Jaguar XJR-6 — Eddie Cheever / Derek Warwick (Tom Walkinshaw Racing)

#8 Joest Racing 956 — Klaus Ludwig / Paolo Barilla / John Winter

As the tricolor falls, Stuck launches perfectly — the 962C’s 2.6-litre twin-turbo engine roaring to 350 km/h on the Mulsanne.

Behind, the Jaguars thunder, their V12s screaming defiance.

For the first time in years, Porsche isn’t racing its own reflection — it’s racing the future.

Hour 1 (5:00 PM) — The Pace of Perfection

The first hour is an exhibition. Stuck leads, lapping at 3′27″ pace — faster than qualifying speeds from two years ago.

Holbert radios: “Car feels perfect. Boost at one-point-two, no heat issues.”

The works Porsches settle into formation, the Jaguars hanging on bravely but consuming twice the fuel.

By 5 PM, Porsche holds the top two positions. The Joest 956, now outdated, still clings to fifth.

Hours 2–3 (6–7 PM) — Engineering as Art

As the evening light softens, the 962Cs run like metronomes. Every pit stop choreographed to seconds, every driver change seamless.

Wollek’s #2 car shadows Stuck and Bell, waiting for the first mistake.

Behind them, the Joest and Brun privateer cars duel for pride.

At 6:40 PM, the Jaguars suffer the first of many gearbox issues — Warwick’s XJR-6 crawls into the pits. The British challenge evaporates almost as soon as it began.

By 7 PM, Porsche’s factory fleet owns the front of Le Mans again.

Hours 4–8 (8 PM – Midnight) — The Night Shifts

Darkness falls under warm air and perfect mechanical harmony.

Bell drives with his signature serenity, conserving brakes and fuel. Holbert takes over at 10 PM, keeping steady 3′32″ laps.

Then, at 11:25 PM — disaster.

The sister car, #2 Porsche 962C (Mass/Wollek/Schuppan), crashes heavily at the kink before Mulsanne Corner after a tyre failure. The car disintegrates against the barriers and bursts into flames.

Miraculously, Jochen Mass escapes, but the wreck burns fiercely, lighting the forest orange.

The safety cars circle for nearly an hour. The paddock falls silent.

At midnight, Bell radios from the leading car: “We’ll keep going — for them.”

Hours 9–12 (Midnight – 3 AM) — Racing Through Grief

Le Mans continues in eerie quiet.

Holbert, Bell, and Stuck maintain their rhythm, but no one celebrates their pace. The #1 962C leads comfortably, followed by the Brun Porsche #19 and Joest’s aging 956.

At 2 AM, rain begins — a soft drizzle turning the Mulsanne into glass.

Holbert tip-toes through it, headlights carving through mist and melancholy.

By 3 AM, they lead by four laps.

Hours 13–16 (3 AM – 6 AM) — Dawn of Endurance

Bell takes over at 4 AM. The rain lifts, leaving a cold silver sky.

His calm, deliberate driving keeps the 962C flawless.

Meanwhile, the Brun Porsche, driven by Sarel van der Merwe, runs second but suffers gearbox vibration.

At 6 AM, the sun rises — pale gold over exhaustion and resilience.

The #1 Rothmans 962C has completed 245 laps without a single unscheduled stop.

Hours 17–20 (6 AM – 10 AM) — Perfection and Precision

The morning brings dry tarmac and renewed purpose.

Holbert, Stuck, and Bell switch seamlessly. The gap grows to six laps.

The only threat is mechanical — or the ghosts of the night before.

At 8 AM, Holbert sets the race’s fastest lap: 3′23.9″, the first to break the 240 km/h barrier average for a lap.

Porsche’s engineering dominance is total.

By 10 AM, the Rothmans pit is quiet confidence — fuel, tyres, brakes, all in harmony.

Hours 21–23 (10 AM – 1 PM) — The Machine and the Men

Le Mans softens into stillness. The privateer 956s trail far behind.

Spectators sense history — the first great 962C victory, but one written in the shadow of loss.

At noon, Bell takes his final stint. He drives with serenity, no longer racing the clock but time itself.

Holbert waits, helmet in lap, eyes distant. He will take the flag.

Hour 24 (1 PM – 2 PM) — Triumph and Tragedy

At 2 PM on June 15, 1986, Derek Bell, Hans-Joachim Stuck, and Al Holbert cross the line in the Porsche 962C #1, completing 4,996.61 km @ 208.6 km/h.

The crowd rises. Porsche has triumphed again — but the joy feels muted.

Mass’s crash the night before lingers in every heart.

Holbert steps from the car, points to the sky, and whispers, “For Jochen.”

Bell removes his helmet slowly. His face says everything — victory and grief, intertwined forever.

Aftermath & Results

Winners: Derek Bell / Hans-Joachim Stuck / Al Holbert — Porsche 962C Rothmans Works Team

Distance: 4,996.61 km @ 208.6 km/h

Second: Sarel van der Merwe / Oscar Larrauri / Jean-Claude Andruet — Porsche 956 Brun Motorsport (+7 laps)

Third: Paolo Barilla / Klaus Ludwig / John Winter — Porsche 956 Joest Racing (+10 laps)

Fastest Lap: Al Holbert (Porsche 962C) — 3′23.9″ (~240 km/h)

Significance:

First Le Mans victory for the Porsche 962C, establishing it as the new icon of Group C.

Porsche’s 11th overall win, and its 6th consecutive since 1981.

Derek Bell’s fourth Le Mans triumph, cementing his reputation as the ultimate endurance craftsman.

A race forever marked by Jochen Mass’s fiery crash, a reminder that dominance never comes without danger.

The year engineering perfection met human vulnerability — a defining image of the 1980s.

Le Mans 1986 was not simply won.

It was endured — a triumph in the shadow of fire.

Sources

Automobile Club de l’Ouest (ACO) — Official 1986 24 Heures du Mans Results & Incident Report

Porsche Werk Weissach Archives — “962C Project Development and Race Telemetry 1986”

Motorsport Magazine, July 1986 — “Triumph and Tragedy at Le Mans”

Goodwood Road & Racing — “1986: The Year the 962 Conquered Le Mans”

Joest & Brun Motorsport Team Logs — “Privateer 956 Endurance Performance Data 1986”

1987 — The Siege of the Silver Fortress

Hour 0 (4:00 PM) — Green Versus Silver

June 13, 1987.

The Circuit de la Sarthe shimmers beneath 30 °C heat — the hottest Le Mans in a decade.

On the grid, the roar of twelve-cylinders and turbos blends into thunder.

Front row:

#17 Porsche 962C (Rothmans Porsche AG) — Hans-Joachim Stuck / Derek Bell / Al Holbert

#18 Porsche 962C (Rothmans Porsche AG) — Jochen Mass / Bob Wollek

#4 Jaguar XJR-8 LM (Tom Walkinshaw Racing) — Eddie Cheever / Raul Boesel / Jan Lammers

#8 Joest 956B — Klaus Ludwig / Paolo Barilla / Louis Krages (“John Winter”)

For the first time in years, Porsche’s dominance looks vulnerable. The green Jaguars are loud, light, and fearless — but Le Mans is not won by noise.

The tricolor falls. Stuck launches cleanly, Bell in pursuit. The Jaguars surge to second and third — a flash of green and gold between the silver arrows.

The war for endurance has begun.

Hour 1 (5:00 PM) — British Fire

The Jaguars charge, their naturally aspirated V12s bellowing at 7,000 rpm. On the straights, they match Porsche for top speed — 372 km/h with no turbo lag.

Boesel’s #4 car briefly leads into Tertre Rouge. The grandstands erupt; after 30 years, Britain smells blood.

But the Porsches are calm. Holbert signals Stuck to let the Jaguars run hot. Le Mans will come to them.

By 5 PM, #17 Porsche leads by seconds. The air shimmers with heat and pride.

Hours 2–3 (6–7 PM) — The Heat That Kills

The temperature climbs to 33 °C. Radiators boil, tyres blister.

At 6 PM, Jaguar’s #5 XJR-8 (Lammers/Watson/Dumfries) pits early — water-pump failure. Ten minutes later, #4 loses oil pressure.

The green challenge crumbles under the sun.

At 7 PM, both Jaguars retreat to the garage. The British invasion ends before dusk.

The Porsches resume their familiar rhythm, lapping effortlessly in the 3′30″s.

Hours 4–8 (8 PM – Midnight) — Order Restored

Dusk turns Le Mans gold and violet. The 962Cs glide like aircraft.

Stuck’s driving is transcendent — 3′23.9″, 3′24.1″, 3′23.8″ — the fastest sustained pace ever seen in the race.

Bell takes over at 10 PM, slowing the tempo to preserve brakes.

The Joest and Brun privateer Porsches follow in procession; six 962s run in the top seven.

By midnight, Porsche leads 1–2–3.

Hours 9–12 (Midnight – 3 AM) — Night Without Fear

For the first time in years, the leading car shows no weakness.

Holbert drives through the night, radioing only fuel figures and lap times. The 962C hums steadily, its ground-effect tunnels roaring softly through the fog.

At 1 AM, Bell returns to the cockpit. He is 45 years old and still the smoothest man at Le Mans.

The gap to #18 car: two laps.

At 3 AM, the heat breaks; a cool breeze moves through the trees. Le Mans exhales.

Hours 13–16 (3 AM – 6 AM) — The Sun of Successors

Dawn reveals the fallen: Jaguars gone, Mazdas broken, Rondeaus silent.

Only Porsches remain — eleven still running.

Holbert takes the sunrise stint. Each lap is within two-tenths of the next.

By 6 AM, the #17 Rothmans Porsche has lapped the field.

Norbert Singer watches from the pit wall, notebook in hand. He says softly,

“The 962 is no longer a car. It’s a system.”

Hours 17–20 (6 AM – 10 AM) — The March of Machines

The morning passes in mechanical perfection.

Bell’s final double stint is steady, respectful, almost elegiac.

At 9 AM, the #18 sister car suffers a gearbox fault, ending any team orders.

Holbert and Stuck are free to finish as they wish — and they do so flawlessly.

By 10 AM, they lead by nine laps.

Hours 21–23 (10 AM – 1 PM) — Endurance as Elegance

The last hours are a study in stillness.

Spectators nap in the grass. Mechanics watch in silence, their work complete.

At 11:30 AM, Stuck sets one final statement: a 3′23.5″ lap on worn tyres, faster than any qualifying lap of 1982.

He hands the car to Holbert for the run home.

Hour 24 (1 PM – 2 PM) — The Last Golden Hour

At 2 PM on June 14, 1987, Hans-Joachim Stuck, Derek Bell, and Al Holbert cross the line in the Porsche 962C #17, completing 4,997.60 km @ 208.7 km/h — Porsche’s seventh consecutive victory.

Holbert raises both arms from the cockpit, coasting down the pit straight to a roar that feels eternal.

Stuck kneels beside the car, laughing through tears.

Bell, ever composed, simply says: “We drove a perfect day.”

It was the end of the unbroken Porsche dynasty — the last time the works team would stand truly untouchable.

Aftermath & Results

Winners: Hans-Joachim Stuck / Derek Bell / Al Holbert — Porsche 962C Rothmans Works Team

Distance: 4,997.60 km @ 208.7 km/h

Second: Jochen Mass / Bob Wollek / Vern Schuppan — Porsche 962C Rothmans (+20 laps)

Third: Klaus Ludwig / Paolo Barilla / Louis Krages — Porsche 956 Joest Racing (+25 laps)

Fastest Lap: Hans-Joachim Stuck (Porsche 962C) — 3′23.5″ (~241 km/h)

Significance:

Porsche’s 12th overall victory, and 7th in a row (1981-87) — a record unmatched.

Derek Bell’s fifth Le Mans win, equaling Ickx’s tally.

The Jaguar challenge collapsed from over-ambition but signaled the dawn of a new rival era.

The 962C’s final works victory, closing Porsche’s golden reign.

Le Mans 1987 proved endurance could be art — a 24-hour symphony played in perfect tune.

When the sun set that evening, Porsche still ruled the world —

but the growl of the Jaguars in the distance promised the empire’s days were numbered.

Sources

Automobile Club de l’Ouest (ACO) — Official 1987 24 Heures du Mans Results & Fuel Reports

Porsche Werk Weissach Archives — “962C Programme Year Five: Thermal Management and Aero Efficiency”

Motorsport Magazine, July 1987 — “The Siege of the Silver Fortress”

Goodwood Road & Racing — “1987: Porsche’s Last Perfect Victory”

Tom Walkinshaw Racing Records — “XJR-8 LM: Performance Notes Le Mans 1987”

1988 — When the Cat Killed the King

Hour 0 (3:00 PM) — The Sound of Revenge

June 11, 1988.

For the first time in a decade, the grandstands are painted British Racing Green.

The Jaguar XJR-9 LM, built by Tom Walkinshaw Racing, stands on the front row beside the silver titan that has ruled Le Mans since 1981 — the Porsche 962C.

Front row:

#2 Jaguar XJR-9 LM — Jan Lammers / Johnny Dumfries / Andy Wallace

#17 Porsche 962C (Rothmans Porsche AG) — Derek Bell / Hans-Joachim Stuck / Klaus Ludwig

#18 Porsche 962C — Jochen Mass / Bob Wollek

#22 Sauber-Mercedes C9 — Jean-Louis Schlesser / Mauro Baldi

The flag falls. The Jaguars erupt in V12 thunder — deep, organic, earth-shaking — chasing the surgical turbo hiss of the Porsches.

The battle is not Germany versus Britain. It is science versus soul.

Hour 1 (4:00 PM) — The Duel Begins

Ludwig’s Rothmans Porsche leads through the first hour, perfect and precise.

Lammers in the #2 Jaguar stalks him — never over-revving, saving fuel and tyres.

By 4 PM, the green cat slips past on Mulsanne, its 7.0-litre V12 howling at 360 km/h.

The crowd erupts. After seven years, Porsche finally bleeds.

Hours 2–3 (5–6 PM) — British Heat, German Discipline

The temperature climbs past 30 °C. The Jaguars’ V12s gulp fuel and radiate heat; the Porsches, cooler and leaner, play the long game.

At 5:40 PM, the #18 Porsche overtakes the #2 Jaguar during a pit rotation.

The lead changes three times in twenty minutes.

By 6 PM, Lammers retakes control, conserving fuel and tyres to perfection.

For the first time in years, Porsche engineers are forced to gamble.

Hours 4–8 (7 PM – 11 PM) — The Race of Equals

As dusk falls, the circuit glows amber. The Jaguars glide with effortless speed down Mulsanne, their straight-line power undeniable.

The Porsches strike back in the night — braking later, cornering sharper.

At 9 PM, Stuck sets a new race record lap: 3′23.2″.

At 10:30 PM, Lammers counters with 3′24.0″ — only slightly slower, but cleaner.

By midnight, both Jaguars lead, split by seconds from the pursuing Rothmans cars.

The air smells of hot brakes, fuel, and destiny.

Hours 9–12 (Midnight – 3 AM) — The Cat in the Dark

The night belongs to the Jaguars.

Their massive engines, running rich and cool, thrive in the darkness.

Wallace drives with eerie calm, conserving every drop of Shell fuel.

The Porsches, heavier with full tanks and narrow turbos, begin to strain.

At 1 AM, Wollek’s #18 car suffers a slow puncture.

At 2 AM, Ludwig’s #17 car drops a gear.

By 3 AM, the lead belongs fully to Jaguar — a moment Britain has waited for since 1957.

Hours 13–16 (3 AM – 6 AM) — The Balance of Power

Dawn rises crimson over the mist. The #2 Jaguar leads by two laps, but trouble whispers in the gearbox.

Lammers radios: “Third gear slipping.”

The pit wall answers: “Drive around it.”

Behind, Porsche scents weakness. Bell pushes relentlessly, lap after lap, cutting seconds from the deficit.

At 6 AM, the gap is down to one lap.

Le Mans 1988 has become a knife fight.

Hours 17–20 (6 AM – 10 AM) — Heat and Hope

The temperature climbs again; Jaguar’s V12s overheat under the returning sun.

Lammers nurses the gearbox by short-shifting out of corners, never touching third gear again.

At 8 AM, the Porsche closes within 90 seconds.

Then, the German car falters — Ludwig’s throttle linkage sticks at Arnage. The fix costs three minutes.

By 10 AM, the Jaguars lead by a full lap again.

Hours 21–23 (10 AM – 1 PM) — The Final Assault

Porsche throws everything it has. Stuck drives flat-out, averaging 3′25″ laps, the fastest sustained pace of the race.

The 962C screams through traffic, relentless.

But Lammers refuses to break. He drives with both hands and his will — never shifting beyond fourth, feeling every vibration as the gearbox disintegrates beneath him.

Wallace takes over for the final hour, nursing the wounded cat home.

Hour 24 (1 PM – 2 PM) — The End of an Empire

At 2 PM on June 12, 1988, Jan Lammers, Johnny Dumfries, and Andy Wallace cross the line in the Jaguar XJR-9 LM #2, completing 5,332.97 km @ 222.3 km/h — the first British victory in 31 years.

The crowd explodes. Flags wave, tears fall. The Porsche dynasty, undefeated since 1981, is finally broken.

In the pits, Walkinshaw weeps openly.

Lammers, exhausted and shaking, whispers to the car: “We did it. You held together.”

The gearbox, on inspection, has one gear left intact.

Holbert’s Porsche finishes two minutes behind — an empire slain by restraint.

Aftermath & Results

Winners: Jan Lammers / Johnny Dumfries / Andy Wallace — Jaguar XJR-9 LM (TWR)

Distance: 5,332.97 km @ 222.3 km/h

Second: Hans-Joachim Stuck / Klaus Ludwig / Derek Bell — Porsche 962C Rothmans Works Team (+2 minutes)

Third: Jochen Mass / Bob Wollek — Porsche 962C Rothmans (+8 laps)

Fastest Lap: Hans-Joachim Stuck (Porsche 962C) — 3′23.2″ (~242 km/h)

Significance:

Jaguar’s first Le Mans win since 1957, ending Porsche’s seven-year streak.

First Le Mans victory for the XJR-9 LM, powered by a naturally aspirated V12 amid a field of turbos.

A masterclass in discipline under duress — Lammers finishing with a crippled gearbox and perfect control.

Porsche’s last stand as a factory juggernaut before the tide of Jaguar, Sauber-Mercedes, and Peugeot.

A poetic reversal: endurance reclaimed by heart over science.

Le Mans 1988 was more than a race.

It was a catharsis — the sound of thunder answering a dynasty’s silence.

Sources

Automobile Club de l’Ouest (ACO) — Official 1988 24 Heures du Mans Results & Technical Report

Tom Walkinshaw Racing Archives — “XJR-9 LM Programme 1988: Fuel, Gearbox, and Cooling Logs”

Porsche Werk Weissach Reports — “962C vs XJR-9: Thermal and Aero Performance Comparison”

Motorsport Magazine, July 1988 — “When the Cat Killed the King”

Goodwood Road & Racing — “1988: Jaguar’s Return to Le Mans Glory”

1988 — When the Cat Killed the King

Hour 0 (3:00 PM) — The Sound of Revenge

June 11, 1988.

For the first time in a decade, the grandstands are painted British Racing Green.

The Jaguar XJR-9 LM, built by Tom Walkinshaw Racing, stands on the front row beside the silver titan that has ruled Le Mans since 1981 — the Porsche 962C.

Front row:

#2 Jaguar XJR-9 LM — Jan Lammers / Johnny Dumfries / Andy Wallace

#17 Porsche 962C (Rothmans Porsche AG) — Derek Bell / Hans-Joachim Stuck / Klaus Ludwig

#18 Porsche 962C — Jochen Mass / Bob Wollek

#22 Sauber-Mercedes C9 — Jean-Louis Schlesser / Mauro Baldi

The flag falls. The Jaguars erupt in V12 thunder — deep, organic, earth-shaking — chasing the surgical turbo hiss of the Porsches.

The battle is not Germany versus Britain. It is science versus soul.

Hour 1 (4:00 PM) — The Duel Begins

Ludwig’s Rothmans Porsche leads through the first hour, perfect and precise.

Lammers in the #2 Jaguar stalks him — never over-revving, saving fuel and tyres.

By 4 PM, the green cat slips past on Mulsanne, its 7.0-litre V12 howling at 360 km/h.

The crowd erupts. After seven years, Porsche finally bleeds.

Hours 2–3 (5–6 PM) — British Heat, German Discipline

The temperature climbs past 30 °C. The Jaguars’ V12s gulp fuel and radiate heat; the Porsches, cooler and leaner, play the long game.

At 5:40 PM, the #18 Porsche overtakes the #2 Jaguar during a pit rotation.

The lead changes three times in twenty minutes.

By 6 PM, Lammers retakes control, conserving fuel and tyres to perfection.

For the first time in years, Porsche engineers are forced to gamble.

Hours 4–8 (7 PM – 11 PM) — The Race of Equals

As dusk falls, the circuit glows amber. The Jaguars glide with effortless speed down Mulsanne, their straight-line power undeniable.

The Porsches strike back in the night — braking later, cornering sharper.

At 9 PM, Stuck sets a new race record lap: 3′23.2″.

At 10:30 PM, Lammers counters with 3′24.0″ — only slightly slower, but cleaner.

By midnight, both Jaguars lead, split by seconds from the pursuing Rothmans cars.

The air smells of hot brakes, fuel, and destiny.

Hours 9–12 (Midnight – 3 AM) — The Cat in the Dark

The night belongs to the Jaguars.

Their massive engines, running rich and cool, thrive in the darkness.

Wallace drives with eerie calm, conserving every drop of Shell fuel.

The Porsches, heavier with full tanks and narrow turbos, begin to strain.

At 1 AM, Wollek’s #18 car suffers a slow puncture.

At 2 AM, Ludwig’s #17 car drops a gear.

By 3 AM, the lead belongs fully to Jaguar — a moment Britain has waited for since 1957.

Hours 13–16 (3 AM – 6 AM) — The Balance of Power

Dawn rises crimson over the mist. The #2 Jaguar leads by two laps, but trouble whispers in the gearbox.

Lammers radios: “Third gear slipping.”

The pit wall answers: “Drive around it.”

Behind, Porsche scents weakness. Bell pushes relentlessly, lap after lap, cutting seconds from the deficit.

At 6 AM, the gap is down to one lap.

Le Mans 1988 has become a knife fight.

Hours 17–20 (6 AM – 10 AM) — Heat and Hope

The temperature climbs again; Jaguar’s V12s overheat under the returning sun.

Lammers nurses the gearbox by short-shifting out of corners, never touching third gear again.

At 8 AM, the Porsche closes within 90 seconds.

Then, the German car falters — Ludwig’s throttle linkage sticks at Arnage. The fix costs three minutes.

By 10 AM, the Jaguars lead by a full lap again.

Hours 21–23 (10 AM – 1 PM) — The Final Assault

Porsche throws everything it has. Stuck drives flat-out, averaging 3′25″ laps, the fastest sustained pace of the race.

The 962C screams through traffic, relentless.

But Lammers refuses to break. He drives with both hands and his will — never shifting beyond fourth, feeling every vibration as the gearbox disintegrates beneath him.

Wallace takes over for the final hour, nursing the wounded cat home.

Hour 24 (1 PM – 2 PM) — The End of an Empire

At 2 PM on June 12, 1988, Jan Lammers, Johnny Dumfries, and Andy Wallace cross the line in the Jaguar XJR-9 LM #2, completing 5,332.97 km @ 222.3 km/h — the first British victory in 31 years.

The crowd explodes. Flags wave, tears fall. The Porsche dynasty, undefeated since 1981, is finally broken.

In the pits, Walkinshaw weeps openly.

Lammers, exhausted and shaking, whispers to the car: “We did it. You held together.”

The gearbox, on inspection, has one gear left intact.

Holbert’s Porsche finishes two minutes behind — an empire slain by restraint.

Aftermath & Results

Winners: Jan Lammers / Johnny Dumfries / Andy Wallace — Jaguar XJR-9 LM (TWR)

Distance: 5,332.97 km @ 222.3 km/h

Second: Hans-Joachim Stuck / Klaus Ludwig / Derek Bell — Porsche 962C Rothmans Works Team (+2 minutes)

Third: Jochen Mass / Bob Wollek — Porsche 962C Rothmans (+8 laps)

Fastest Lap: Hans-Joachim Stuck (Porsche 962C) — 3′23.2″ (~242 km/h)

Significance:

Jaguar’s first Le Mans win since 1957, ending Porsche’s seven-year streak.

First Le Mans victory for the XJR-9 LM, powered by a naturally aspirated V12 amid a field of turbos.

A masterclass in discipline under duress — Lammers finishing with a crippled gearbox and perfect control.

Porsche’s last stand as a factory juggernaut before the tide of Jaguar, Sauber-Mercedes, and Peugeot.

A poetic reversal: endurance reclaimed by heart over science.

Le Mans 1988 was more than a race.

It was a catharsis — the sound of thunder answering a dynasty’s silence.

Sources

Automobile Club de l’Ouest (ACO) — Official 1988 24 Heures du Mans Results & Technical Report

Tom Walkinshaw Racing Archives — “XJR-9 LM Programme 1988: Fuel, Gearbox, and Cooling Logs”

Porsche Werk Weissach Reports — “962C vs XJR-9: Thermal and Aero Performance Comparison”

Motorsport Magazine, July 1988 — “When the Cat Killed the King”

Goodwood Road & Racing — “1988: Jaguar’s Return to Le Mans Glory”

1989 — The Silver Storm

Hour 0 (3:00 PM) — The Return of the Star

June 10, 1989.

The Circuit de la Sarthe trembles.

For the first time since 1955, the Silver Arrows of Mercedes-Benz return — sleek, titanium-skinned Sauber-Mercedes C9s.

The grid is a tapestry of eras colliding:

#63 Sauber-Mercedes C9 — Jochen Mass / Manuel Reuter / Stanley Dickens

#62 Sauber-Mercedes C9 — Jean-Louis Schlesser / Mauro Baldi / Kenneth Acheson

#17 Porsche 962C — Hans-Joachim Stuck / Derek Bell / Bob Wollek

#4 Jaguar XJR-9 LM — Andy Wallace / Jan Lammers / Johnny Dumfries

#55 Mazda 767B — Herbert / Kennedy / Dieudonné

Under the tricolor flag, the Mercs thunder down to Dunlop — V8 twin-turbos shrieking like afterburners.

By the end of lap 1, they’ve already hit 400 km/h on Mulsanne.

The Silver Arrows have returned to Le Mans, and the air itself seems afraid.

Hour 1 (4:00 PM) — Power and Precision

The two Saubers pull away relentlessly, 30 seconds clear after the first hour.

Schlesser leads, Mass follows — a formation flight in polished steel.

Behind them, Stuck’s Porsche 962 fights to keep pace, its aging aerodynamics outclassed.

The Jaguars, geared shorter, struggle for top-end speed but shine through the corners.

By 4 PM, Mercedes runs 1-2. Their pit wall is calm, clinical — this is not a comeback. It’s an occupation.

Hours 2–3 (5–6 PM) — Heat and Hunger

The afternoon grows unbearable. Track temperature hits 57 °C.

The 962s begin to cook their gearboxes. Jaguars lose brakes.

Inside the C9, the cockpit temperature reaches 60 °C, but the cars never falter.

Reuter radioes in: “Boost is stable, tires clean. We can go faster.”

Mercedes engineers reply: “Do not. We are not racing men — we are racing time.”

At 6 PM, the #63 car leads by one lap.

Hours 4–8 (7 PM – 11 PM) — The Sound of Speed

As dusk descends, the C9s continue their march.

Each lap is an assault on physics — 3′15″ pace, 250 km/h averages, nearly F1-fast down the straights.

At 8 PM, Jochen Mass clocks 407 km/h on the Mulsanne — the highest verified speed ever recorded at Le Mans.

In the pits, Schlesser wipes sweat from his neck and whispers, “We cannot go faster than this.”

He is right.

By midnight, the cars have covered nearly half the race distance — a full lap ahead of the Jaguars and Porsches.

Hours 9–12 (Midnight – 3 AM) — When Darkness Can’t Catch You

Night at Le Mans is supposed to humble machines.

But the Saubers carve through it like silver phantoms.

The black paint on the rear panels, meant for heat dissipation, glows faint red.

The twin turbos shriek as Mass and Reuter alternate double stints, never missing a beat.

At 2 AM, the #61 Mercedes suffers oil pressure loss and retires. The #63 and #62 continue untouched.

The Porsches fade, the Jaguars limp.

At 3 AM, the #63 holds a five-lap lead.

Hours 13–16 (3 AM – 6 AM) — Endurance by Design

Dawn breaks over fog and fatigue.

Schlesser climbs into the #62 car and pushes — 3′21″, 3′22″, 3′22″ — relentless precision.

Behind, the factory Porsche of Stuck/Bell/Wollek claws back seconds per lap, but the gap remains four laps.

Jaguar’s challenge dissolves entirely by sunrise; their V12s can’t survive the pace.

At 6 AM, Mercedes still leads 1-2.

Hours 17–20 (6 AM – 10 AM) — When the Past Falls Silent

Porsche’s final counterattack ends in heartbreak.

At 8:05 AM, the #17 car retires with engine failure — its final cry echoing through the forest.

The Silver Arrows now own the track.

Schlesser’s #62 and Mass’s #63 run nose-to-tail through traffic, orchestrated by stopwatches and faith.

Norbert Kreyer, Mercedes engineer, murmurs: “Thirty-four years. We have waited thirty-four years.”

Hours 21–23 (10 AM – 1 PM) — The Procession of Perfection

By late morning, the race is already decided.

Mercedes slows the pace, preserving engines. Even throttled back, they lap faster than anyone else.

The only tension now lies in history itself — could the curse of 1955 finally be lifted?

At noon, Reuter straps in for the final stint. He drives without words, focused on every vibration, every prayer.

Hour 24 (1 PM – 2 PM) — The Return of the Silver Arrows

At 2 PM on June 11, 1989, Jochen Mass, Manuel Reuter, and Stanley Dickens cross the line in the Sauber-Mercedes C9 #63, completing 5,791.77 km @ 240.9 km/h — the fastest 24 Hours of Le Mans ever run.

The pit wall explodes in restrained joy. Schlesser embraces Norbert Singer, both men smiling through decades of silence.

Mercedes had returned to Le Mans — and to redemption.

Mass stands atop the C9, silver suit streaked with oil and sweat, and shouts, “This is what 1955 owed us!”

The ghosts are gone. The storm has passed.

Le Mans belongs to the star once more.

Aftermath & Results

Winners: Jochen Mass / Manuel Reuter / Stanley Dickens — Sauber-Mercedes C9

Distance: 5,791.77 km @ 240.9 km/h (Record)

Second: Jean-Louis Schlesser / Mauro Baldi / Kenneth Acheson — Sauber-Mercedes C9 (+5 laps)

Third: Kenny Acheson / Baldi / Schlesser — (sister car; classified finish)

Fourth: Derek Bell / Hans-Joachim Stuck / Bob Wollek — Porsche 962C (+10 laps)

Fastest Lap: Jochen Mass (Sauber-Mercedes C9) — 3′15.0″ (~252 km/h)

Significance:

Mercedes’ first Le Mans victory since 1952, ending 34 years of absence and tragedy.

Fastest average speed in Le Mans history, a record that stood until circuit changes in 1990.

The final year of the uninterrupted Mulsanne Straight — after 1989, chicanes would tame the monster.

Porsche’s dynasty ended not by misfortune, but by evolution.

The year Le Mans became too fast even for itself — the ultimate crescendo of the Group C age.

Le Mans 1989 was not merely a race.

It was atonement written in speed — a 34-year breath finally exhaled in silver.

Sources

Automobile Club de l’Ouest (ACO) — Official 1989 24 Heures du Mans Results & Telemetry Logs

Sauber-Mercedes Archives — “C9 Race Report: Mulsanne Aerodynamics and Engine Efficiency 1989”

Porsche Werk Weissach — “962C Endurance Programme Phase Out Summary”

Motorsport Magazine, July 1989 — “The Silver Storm”

Goodwood Road & Racing — “1989: The Year Le Mans Hit 400 km/h”

1990 — The Last Roar of the V12

Hour 0 (3:00 PM) — The New Le Mans

June 16, 1990.

The crowd looks restless — the Mulsanne Straight, once a mythic runway, now wears two awkward scars: the new chicanes, built to end the 400 km/h madness of 1989.

But though the straight is slower, the field is faster in spirit.

Front row:

#1 Sauber-Mercedes C11 — Jean-Louis Schlesser / Mauro Baldi / Alain Ferté

#3 Nissan R90CK — Mark Blundell / Julian Bailey / Gianfranco Brancatelli

#35 Jaguar XJR-12 — Andy Wallace / Martin Brundle / John Nielsen

#36 Jaguar XJR-12 — Jan Lammers / Price Cobb / Eliseo Salazar

The tricolor drops — and history exhales.

Schlesser rockets away, the Mercedes howling with twin-turbo fury, but Brundle’s green-and-purple Jaguar launches cleaner, sliding into second by Dunlop.

For the first time since 1988, Jaguar is the hunter and the hunted.

Hour 1 (4:00 PM) — Chicanes and Chaos

The first hour is frenetic. Drivers fight to learn the new rhythm — brake, turn, accelerate, brake again.

The C11s surge down Mulsanne like guided missiles, but the Jaguars’ V12s sound like a symphony in comparison.

At 3:40 PM, Blundell’s Nissan R90CK bursts into view — its turbo boost mis-set, delivering 1,000 bhp in qualifying trim. It storms to the lead, clocking 3′27.0″ despite the chicanes. The crowd gasps.

But ten laps later, the boost valve fails. The miracle ends.

By 4 PM, Schlesser’s Mercedes leads, Brundle’s Jaguar follows, and endurance begins its long descent into dusk.

Hours 2–3 (5–6 PM) — Silver vs Green

The Mercedes C11s look invincible: lighter, newer, more efficient.

Yet the Jaguars counter with simplicity — fewer electronics, longer fuel stints, bulletproof reliability.

At 5:30 PM, the first chicane claims a victim: the Courage Porsche 962C slides off under braking, scattering debris.

Under yellow, Brundle stays glued to the Sauber’s rear wing, waiting.

When green flies, he lunges — the XJR-12 roars past into Tertre Rouge.

Le Mans cheers. Jaguar leads again.

Hours 4–8 (7 PM – 11 PM) — Into the Night

As twilight falls, both Mercedes and Jaguar play chess.

The C11s pit more often but run blistering lap times; the Jaguars run 24-lap stints, saving a stop every two hours.

At 9 PM, the first signs of strain appear.

Ferté’s C11 develops a sticking throttle. Baldi radios, “Temperature rising.”

Walkinshaw’s men smile. “They’re pushing too hard.”

By midnight, #35 Jaguar (Brundle/Wallace/Nielsen) leads by one lap.

Hours 9–12 (Midnight – 3 AM) — The Longest Night

The temperature drops to 8 °C. The Jaguars’ big V12s, once a liability, now breathe perfect air.

Brundle’s rhythm is flawless: 3′41″, 3′42″, 3′42″ — hour after hour.

Behind, Schlesser’s silver C11 runs into gearbox trouble at 1 AM. The sister #2 car inherits second, but even it begins to show fuel-pump strain.

At 3 AM, the Sauber pit wall grows tense.

At 3:07, the #1 Mercedes retires.

For the first time in the race, Walkinshaw dares to smile.

Hours 13–16 (3 AM – 6 AM) — Jaguar Unleashed

Dawn spills orange over the circuit. The Jaguars roar on, untroubled.

The #35 car leads by two laps, the #36 car by three behind it.

Wallace climbs in, drives like a ghost — precise, unyielding, smooth.

At 6 AM, the lead is four laps.

The silver arrows have dimmed. The cat stretches and yawns.

Hours 17–20 (6 AM – 10 AM) — Heat and Hope

As the sun returns, the track temperature soars again.

The Jaguars’ oil temps climb past 120 °C, forcing shorter stints.

At 8 AM, the #35 car develops a slow puncture. A flawless pit stop keeps the lead intact.

Behind them, Nissan’s private R90CK surges back into contention, chasing for a podium.

By 10 AM, Jaguar still leads — but the rhythm is fragile.

Hours 21–23 (10 AM – 1 PM) — The Pressure Mounts

The Sauber engineers beg their drivers to attack.

Baldi’s #2 car runs a 3′33″ lap — faster than any Jaguar can match.

But Brundle responds with calm genius: instead of pushing, he slows down, conserving fuel for the final two hours.

At 12:30 PM, the gap is still two laps. The team radios:

“Martin, no risks now.”

He replies: “Tell Tom the cat’s still hunting.”

Hour 24 (1 PM – 2 PM) — Glory and Goodbye

At 2 PM on June 17, 1990, Martin Brundle, Andy Wallace, and John Nielsen cross the line in the Jaguar XJR-12 #35, completing 4,882.41 km @ 203.2 km/h.

The crowd roars — the first back-to-back victory for Jaguar since the 1950s.

Behind them, Sauber’s C11 limps home second, defeated not by speed but by fuel and fatigue.

Nissan celebrates third — a new power rising from Japan.

Brundle climbs from the cockpit, face streaked with sweat, and whispers to Walkinshaw,

“She never missed a beat.”

Walkinshaw just nods. “Neither did you.”

The V12 idles once more, then falls silent — its final roar echoing across decades of British glory.

Aftermath & Results

Winners: Martin Brundle / Andy Wallace / John Nielsen — Jaguar XJR-12 (TWR)

Distance: 4,882.41 km @ 203.2 km/h

Second: Jean-Louis Schlesser / Mauro Baldi / Alain Ferté — Sauber-Mercedes C11 (+2 laps)

Third: Mark Blundell / Julian Bailey / Gianfranco Brancatelli — Nissan R90CK (+5 laps)

Fastest Lap: Jean-Louis Schlesser (Sauber-Mercedes C11) — 3′33.0″ (~237 km/h)

Significance:

First Le Mans under the new chicaned Mulsanne layout, ending the 400 km/h era.

Jaguar’s seventh and final overall victory, and Martin Brundle’s defining endurance triumph.

Mercedes’ final Group C appearance before its 1990s F1 return.

The rise of Nissan as Japan’s new endurance force.

A race that closed one chapter and quietly began another — speed giving way to strategy.

Le Mans 1990 wasn’t about violence.

It was about grace — the art of lasting longer than power itself.

Sources

Automobile Club de l’Ouest (ACO) — Official 1990 24 Heures du Mans Results & Technical Reports

Tom Walkinshaw Racing Archives — “XJR-12 Programme: Fuel Efficiency and Reliability Study”

Sauber-Mercedes Engineering Notes — “C11 Telemetry and Power Curve Comparison 1990”

Motorsport Magazine, July 1990 — “The Last Roar of the V12”

Goodwood Road & Racing — “1990: Jaguar’s Final Triumph at Le Mans”

1991 — The Song of the Rotary

Hour 0 (3:00 PM) — The Howl from Hiroshima

June 22, 1991.

The air over Le Mans hums with heat and expectation. The new 3.5-litre Formula rules loom over the future, but this year, the past has come to sing its final note — a strange, shrieking four-rotor engine called the Mazda 787B.

Front row:

#1 Mercedes C11 — Jean-Louis Schlesser / Jochen Mass / Alain Ferté

#55 Mazda 787B — Johnny Herbert / Volker Weidler / Bertrand Gachot

#16 Jaguar XJR-12 — Andy Wallace / Derek Warwick / John Nielsen

#35 Porsche 962C — Hans Stuck / Bob Wollek / Derek Bell

The #55 Mazda, liveried in shocking orange-and-green Renown/Charge, idles like a swarm of hornets.

Its wail is mechanical art — 900 kg, 700 horsepower, and no pistons.

The flag falls. The field erupts. The Mercedes leads cleanly into Dunlop, but the Mazda’s rotary howl slices through the field like a siren.

The last great underdog story begins.

Hour 1 (4:00 PM) — The Silver Lead

The opening hour belongs to Mercedes. The C11s, low and silver, glide through traffic, fuel-efficient and flawless.

Mazda sits quietly in fourth — Weidler driving with surgical restraint, short-shifting the rotary to save fuel.

At 4 PM, Schlesser leads from Mass, followed by Jaguar’s V12s. Mazda watches and waits.

Hours 2–3 (5–6 PM) — The Strategy of Silence

Mazdaspeed’s engineers know they cannot outpace the Germans — only outlast them.

The 787B is tuned for reliability: its 2.6-litre 4-rotor R26B engine revs to 9,000 rpm but sips fuel like a V6.

At 5:30 PM, the Jaguars pit early for tyres.

By 6 PM, Mazda quietly rises to third.

Herbert radios: “Car feels perfect — she’s singing.”

Hours 4–8 (7 PM – 11 PM) — Into the Golden Light

The sun begins to fall. The Mercedes continue their relentless pace, but small cracks appear: vibrations, brake wear, rising gearbox temps.

Mazda, meanwhile, runs metronomic laps — 3′41″, 3′42″, 3′41″ — hour after hour.

At 9 PM, one of the Sauber-Mercedes cars (#32) develops oil pressure trouble.

By midnight, the Mazda 787B is second overall.

No one believes what they’re seeing.

Hours 9–12 (Midnight – 3 AM) — The Quiet Revolution

The night belongs to the orange car.

While the turbocharged Porsches and Mercedes gulp air and strain under boost, the Mazda hums — its exhaust glowing blue, its note echoing across Arnage.

At 1:12 AM, the lead Mercedes, Schlesser at the wheel, pits with gearbox issues.

Mazda inherits the lead.

Team principal Takayoshi Ohashi whispers to his engineers, “Do not celebrate. We have twelve hours to live.”

Hours 13–16 (3 AM – 6 AM) — Dawn of the Impossible

As the mist rises over the circuit, Weidler climbs back in. He is relentless — lap after lap, perfect throttle control, brake bias untouched, conserving fuel to the millilitre.

Behind, Jaguar and Mercedes trade second place, but both begin to fade. The 787B just keeps singing.

By sunrise, Mazda has led 80 consecutive laps.

Spectators, half-asleep, begin to understand they are watching history being written.

Hours 17–20 (6 AM – 10 AM) — Pressure Without Error

The sun climbs higher, the pace intensifies.

Schlesser’s repaired C11 starts closing the gap — 12 seconds per lap faster.

Mazdaspeed’s radio stays eerily calm. Gachot responds with consistency, never panicking.

At 9:30 AM, a Porsche spins at Mulsanne, bringing out a yellow. Mazda uses it to refuel strategically, keeping the lead.

At 10 AM, the gap to second is three laps.

The crowd begins to cheer every pass of the green-and-orange blur.

Hours 21–23 (10 AM – 1 PM) — The Marathon Becomes a Miracle

Every engineer expects the 787B to fail — rotaries have never lasted this long.

But hour after hour, it remains perfect.

At noon, the sister Mazdas (#18 and #56) retire — their engines fine, but gearboxes spent.

Now all hope rests on one car — chassis 002, the lead #55.

Herbert climbs in for the final stint.

He drives as if possessed. 3′42″, 3′42″, 3′41″ — every lap within a second.

Hour 24 (1 PM – 2 PM) — The Howl of Victory

At 2 PM on June 23, 1991, Johnny Herbert, Volker Weidler, and Bertrand Gachot cross the line in the Mazda 787B #55, completing 4,932.25 km @ 205.3 km/h.

The rotary scream becomes a roar of redemption.

Japan has won Le Mans — the first, and still the only, Asian manufacturer to do so.

Herbert parks the car, exhausted, dehydrated, and delirious. He never makes it to the podium — he’s carried to the medical center instead.

As he lies on the cot, he hears the sound of the crowd — a sea of applause for a sound they’ll never forget.

Mazda has done the unthinkable.

No turbos. No pistons. No compromise.

Only music.

Aftermath & Results

Winners: Johnny Herbert / Volker Weidler / Bertrand Gachot — Mazda 787B (Mazdaspeed)

Distance: 4,932.25 km @ 205.3 km/h

Second: Jean-Louis Schlesser / Alain Ferté / Jochen Mass — Sauber-Mercedes C11 (+2 laps)

Third: Andy Wallace / Derek Warwick / John Nielsen — Jaguar XJR-12 (+6 laps)

Fastest Lap: Jean-Louis Schlesser (Sauber-Mercedes C11) — 3′35.0″ (~239 km/h)

Significance:

First and only Japanese manufacturer to win Le Mans overall.

First and only rotary engine victory — the R26B’s final, glorious outing before being banned the following year.

Mazda’s first and only overall win, achieved without factory Porsche or Mercedes budgets.

A triumph of efficiency, durability, and courage, proving that innovation still had a place in endurance racing.

The victory became a national legend — the howl of Hiroshima echoing across the world.

Le Mans 1991 was not just a race.

It was an aria of defiance — the sound of a small company daring to dream louder than giants.

Sources

Automobile Club de l’Ouest (ACO) — Official 1991 24 Heures du Mans Race Report & Results

Mazda Motor Corporation Archives — “787B Chassis 002: Endurance Development Log”

Mazdaspeed Europe Technical Notes — “R26B Rotary Engine Performance at Le Mans 1991”

Motorsport Magazine, July 1991 — “The Song of the Rotary”

Goodwood Road & Racing — “1991: Mazda’s Howl of Glory”

1992 — The Lion’s Awakening

Hour 0 (3:00 PM) — A New Breed on French Soil

June 20, 1992.

A low, humid heat settles over the Circuit de la Sarthe.

The grid looks unlike any in Le Mans history — sleek, narrow, single-seaters in disguise. The mighty Group C cars have been slimmed down by regulation, transformed by the 3.5-litre “Formula 1-style” rules meant to replace the old turbo monsters.

Front row:

#1 Peugeot 905 Evo 1B — Derek Warwick / Yannick Dalmas / Mark Blundell

#2 Peugeot 905 Evo 1B — Mauro Baldi / Philippe Alliot / Jean-Pierre Jabouille

#33 Toyota TS010 — Geoff Lees / Andy Wallace / Masanori Sekiya

#8 Mazda MXR-01 — Mauricio Sandler / Johnny Herbert / Volker Weidler

Peugeot’s white and blue lions gleam under the clouds — France’s answer to Porsche’s dynasty, to Jaguar’s power, to Mazda’s miracle.

When the tricolor falls, the Peugeots leap forward in perfect unison, their V10s screaming at 13,000 rpm — F1 sound on endurance soil. The crowd erupts.

For the first time since 1950, France believes it will win its own race.

Hour 1 (4:00 PM) — The Formula of Endurance

The new 3.5-litre cars are razor-edged — faster in corners, fragile in hearts.

Blundell’s #1 Peugeot leads from Alliot’s #2; the Toyota TS010 follows half a second behind.

At 4 PM, Blundell sets the tone with a 3′32.5″ lap — faster than anything since the Mulsanne chicanes were built.

The Peugeots are poetry in motion — stable, predictable, unstoppable.

Behind them, the Mazdas and old privateer 962s fight their last stand, their turbos lagging in protest against a new age.

Hours 2–3 (5–6 PM) — The Charge of the Lion

The afternoon becomes a sprint. Peugeot pits both cars in quick succession — 25 seconds for fuel, slicks, driver change.

Toyota responds, keeping pace.

By 6 PM, both Peugeots have lapped the field.

The #1 car runs flawlessly, Warwick keeping it in a rhythm that seems unbreakable.

In the garages, engineers whisper: “We have turned Le Mans into a six-hour sprint repeated four times.”

Hours 4–8 (7 PM – 11 PM) — Nightfall in the New Order

Dusk comes quietly. The Peugeots now run first and second.

The #33 Toyota, though quick, burns its rear tyres and struggles with fuel range.

At 9 PM, the #2 Peugeot slows — electrical misfire. Alliot nurses it to the pits.

In the calm chaos, the #1 car stretches its lead to three laps.

By midnight, Blundell hands over to Dalmas. The white lion howls into the night, unchallenged.

Hours 9–12 (Midnight – 3 AM) — A French Night

For the first time in years, the night at Le Mans feels tranquil.

The new cars’ engines sing in clean harmony; there are no turbo explosions, no rotary screams — only mechanical precision.

At 1 AM, #33 Toyota TS010 suffers gearbox vibration, dropping three laps.

At 2 AM, Peugeot #2 returns after lengthy repair — now seventh overall.

Peugeot’s pit whispers: “Protect #1 at all costs.”

By 3 AM, Warwick’s #1 car leads by four laps.

Hours 13–16 (3 AM – 6 AM) — The End of the Roar

As dawn rises over Arnage, the silver fog reveals what’s left of Group C: two Peugeots, one Toyota, a handful of Mazdas, and ghosts.

At 4:45 AM, the #33 Toyota briefly leads on pit sequence — France holds its breath — but Dalmas reclaims it within two laps.